Star Trek: Picard

“Mercy”

Season 2, Episode 8

Written by Cindy Appel & Kirsten Beyer

Directed by Joe Menendez

Starring Patrick Stewart, Isa Briones, Santiago Cabrera, Evan Evagora, Michelle Hurd, Alison Pill, Jeri Ryan, and Brent Spiner

Guest Starring Ito Aghayere, Jackson Garner, Steve Gutierrez, Jay Karnes, Charles Maceo, Sol Rodriguez, Eduardo Roman, Chuti Tiu, Oscar Torre, and Cyrus Zoghi

Special Guest Star John de Lancie

49 minutes

Original broadcast 21 April 2022

1. Here, There, & Everywhere

With “Mercy,” Star Trek: Picard’s second season enters its closing round, its final stretch, and its last stand. So much has happened in the run-up to this installment that sensible viewers might presume Year 2, with only three episodes remaining, would start consolidating its characters, plots, and themes to begin the inevitable march toward its season finale.

Picard, however, chooses to ignore any levelheadedness that the term sensible implies by following a grand Trek tradition of going for broke as its sophomore excursion nears the end. Star Trek at its best, after all, refuses the playing-it-safe sterility that typifies too much American television, with so many previous Trek episodes stamping the accelerator just when they could (and perhaps should) tap the brakes that it’s easy to lose count. Star Trek, indeed, so frequently refuses the imprecations of fans who prefer its drama to remain patient and reasonable or, in nautical terminology, to strike an even keel that I, for one, admire the franchise’s willingness to embrace audacious, even foolhardy turns of plot, character, theme, and tone.

No matter how dangerous traveling this reckless course may be, the prospects for thrilling drama outweigh the risks of narrative failure, at least just enough to make the journey worthwhile. Such is the case with “Mercy,” an outing that shouldn’t work as well as it does and doesn’t work as well as it should, a statement that, far from damning this segment with faint praise, instead acknowledges that Episode 8 unspools an entertaining hour of television whose advantages outstrip its flaws, but whose defects are too visible to ignore.

“Mercy,” by all rights, should fall into chaos thanks to the proliferating side characters, subplots, and narrative runners inside these subplots (sub-subplots, perhaps, a term as clumsy as it is cumbersome) that force writers Cindy Appel and Kirsten Beyer to remember—even if they can’t account for—every detail that Season 2 jams into its first seven outings. Appel and Beyer must work so devilishly hard to keep Year 2’s storylines aligned, balanced, and moving that they become authorial conductors whose first task—keeping their narrative freight train from running off the rails—cannot compromise their second duty, namely, preserving this runaway locomotive’s—and metaphor’s—anarchic energy despite the jeopardy that, at any moment, they might wreck Season 2’s storytelling enterprise.

This last pun is, I grant you, cheaply—yet sincerely—made. “Mercy,” while far from cheap, extends the sincerity (bordering on earnestness) that long-time Star Trek aficionados now expect from the franchise despite the danger of this solemnity, if left unchecked, curdling into overripe melodrama. This route’s hokeyness brings “Mercy” perilously near the territory that Joel Hodgson’s sublime Mystery Science Theater 3000 has lampooned, without favor or pity, since 1988, so I’m happy to report that “Mercy” equates itself better than anyone might expect given Picard Season 2’s dense narrative, which remains so crowded with incident and portent that it now threatens to capsize under the weight of its own storytelling ambitions.

This episode’s relative success speaks to Appel’s and Beyer’s efforts to wrangle Year 2’s unwieldy elements into a semi-coherent whole, but, in the end, their success can only be partial. Perhaps, however, the problems implied by this judgment are mine (and mine alone). Emphasizing coherence may represent a critically impoverished outlook expressed in diagnostically destitute vocabulary that shoehorns what counts as good storytelling into too small an analytical container. Not all good stories, after all, must wind themselves so tightly that their resulting clockwork precision reminds audience members of finely tuned Swiss watches.

Some of Trek’s most-memorable installments—The Original Series’s delightful “The Trouble with Tribbles”; The Animated Series’s crazy, Walter Koenig-scripted “The Infinite Vulcan”; The Next Generation’s moving “The Inner Light”; Deep Space Nine’s joyful “Take Me Out to the Holosuite”; Voyager’s infamous-but-fabulous “Threshold” (yes, I said it!); Enterprise’s beautifully over-the-top two-parter “In a Mirror Darkly”; and Discovery’s time-loop-on-acid entry “Magic to Make the Sanest Man Go Mad”—defy the boundaries of conventional, humdrum plotting to achieve remarkable, if not always judicious, results. The pleasures afforded by such stories as they amble, ramble, meander, and wander across unexpected narrative terrain are significant, as demonstrated by the best parts of Episode 8’s immediate predecessors (“Two of One” and “Monsters”), yet the enjoyments offered by “Mercy” only advance its storyline 90 or 95 yards down the field before stranding us just shy of the end zone.

Traveling hither and yon this way certainly keeps events rolling pell-mell, with one “Mercy” scene piling atop another in a mad dash that creates high adventure and unhinged excitement. Yet the toll exacted by this installment’s “here, there, and everywhere” narrative approach cages its writers, characters, and viewers before “Mercy” reaches its slam-bang conclusion. This clever cliffhanger once again involves the Borg Queen’s mordant wit, but some of what transpires before this moment, while not exactly objectionable or ineffective, makes “Mercy” an episode whose dramatic reach exceeds its storytelling grasp.

Not by much, I hasten to add, not by much, but just enough to notice.

2. Admirals & Agents

More’s the pity, I say, since “Mercy” begins promisingly, with a young boy sprinting through the nighttime woods, we know not why, in footage well staged by director Joe Menedez, well shot by cinematographer Crescenzo Notarile, and expertly cut together by editor Heydar Adel. This scene then shifts to Jean-Luc Picard (Sir Patrick Stewart) seated at a table inside a dank basement interrogation room. Having been arrested in the final moments of “Monsters,” the good admiral now sits next to Young Guinan (Ito Aghayere) while staring at a bloodstain left on this table’s top to intimidate anyone observing it. Viewers who mistake the opening scene for Picard remembering another childhood incident quickly realize their error when FBI Agent Martin Wells (Jay Karnes) enters the room to interview our heroes, but not, he’s quick to note, interrogate them (despite the distinction meaning little to either prisoner).

Beyond the fact that Jackson Garner, the young actor who plays this fleeing boy, resembles a youthful Jay Karnes much more than either Patrick Stewart or Dylan Von Halle (the performer who’s played Picard’s boyhood self throughout Season 2), Karnes shuffles into the room with the same frustrated urgency that propels his younger incarnation through the woods. This detail—easily missed but deliberately crafted by Menendez, Karnes, and Garner working together to ensure that both actors believably play the same person at two different points in his life—speaks to Episode 8’s careful production even if viewers don’t understand how seeing Wells as a boy relates to Picard’s and Guinan’s efforts to get galactic history back on track.

These flashbacks continue throughout Wells’s interview, with one remembrance dramatizing how Young Martin’s run is, indeed, an escape from unknown pursuers. The boy slips, tumbles down a short hill, and, in a surprising turn of events, reacts in shock when he raises his flashlight to find, of all people, two Vulcans (played by Eduardo Roman and Chuti Tiu) staring at him. This revelation functions as “Mercy’s” dramatic linchpin, certifying the tale told by Enterprise’s Sub-Commander T’Pol (Jolene Blalock)—in that program’s enchanting Season 2 entry “Carbon Creek”—that Vulcans visited Earth before humanity’s official first contact with them on 5 April 2063 (as seen in the marvelous concluding sequence of Star Trek: First Contact, the franchise’s eighth feature film).

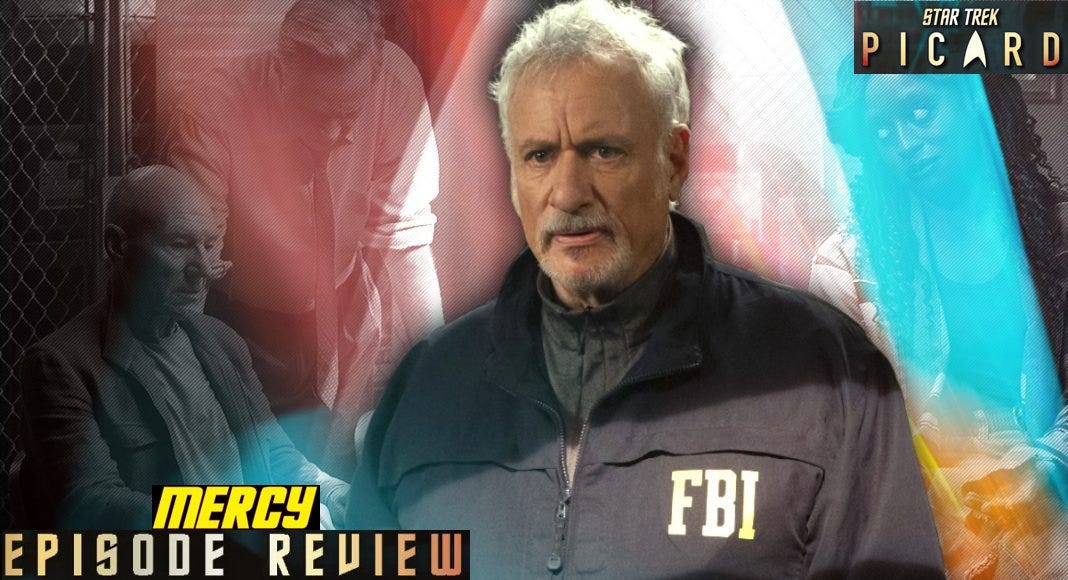

Wells’s story-within-a-story (about his younger self finding extraterrestrials in the forest) exposes him as a kooky, off-kilter, and melancholy outsider, at least as far as his FBI superiors are concerned. Wells doesn’t cut a terribly intimidating figure, either, despite his intelligence and integrity being obvious, reminding us once again of Jay Karnes’s splendid performance as Detective Holland “Dutch” Wagenbach in all seven seasons of Shawn Ryan’s FX cop drama The Shield (2002-2008).

Wells point-blank asks Picard and Young Guinan if they’re extraterrestrials, eliciting laughter from Guinan (who calls the man “buckets of crazy”) and derision from Picard (who pronounces the interrogation “absurd”). This conversation, in what seems a deliberate allusion by Cindy Appel and Kirsten Beyer, recalls more than a few Shield interrogations in which characters on all sides of the law mistake Dutch’s self-effacing nature as personal insecurity.

Wells tells our heroes that the basement room they inhabit is one of those forgotten places where objects and people can easily disappear, but, even in these early moments, viewers know Wells’s threats are empty. He simply doesn’t operate like a spit-and-polish FBI man, a role that Karnes plays much more forthrightly during his five outstanding appearances as Agent Robert Gale in 12 Monkeys (2015-2018), the SyFy Channel adaptation of Terry Gilliam’s 1995 film Twelve Monkeys (co-created by Picard showrunner Terry Matalas and co-producer Travis Fickett) whose time-tripping narrative provides both broad templates and specific patterns for Star Trek: Picard’s sophomore season.

Wells doesn’t frighten Picard or Young Guinan, either, although Karnes’s terrific work in the disturbing, David Mamet-directed Season 3 Shield episode “Strays”—to say nothing of his noteworthy turn as Josh Kohn, a psychopathic ATF agent who bedevils the antihero protagonists of Kurt Sutter’s Hamlet-in-California motorcycle drama Sons of Anarchy (2008-2014) during this rough-and-tumble program’s first season—proves how fearsome an onscreen presence he can be.

No, if anything, Martin Wells resembles a timid version of David Duchovny’s basement-dwelling, alien-tracking FBI Agent Fox Mulder in Chris Carter’s now-classic conspiracy thriller The X-Files (1993-2002, 2016, 2018), although Mulder remains unflappable where Wells appears uncertain. Focusing so much attention upon Wells’s lifelong obsession with locating extraterrestrial life on Earth paradoxically makes Cindy Appel’s, Kirsten Beyer’s, and their boss Terry Matalas’s dramatic choices seem unfocused, leaving “Mercy” at the mercy of seemingly insignificant details that add up to an unsatisfying sum.

3. On (& Off) Star

This judgment isn’t as harsh as it sounds. Jay Karnes is predictably terrific, but his prominence throughout “Mercy” forces careful viewers to wonder why this installment concentrates so much time and cedes so much space to a secondary character who may never appear again.

The answer involves Matalas’s fondness for the A/B/C/D story pattern that has typified American television since the 1950s, a tradition so entrenched that even serialized programs embrace it. Matalas and his writing staff lard Picard Season 2 with so many plots, characters, themes, and details that, in “Mercy,” they venture down the alphabet path a few letters beyond D, requiring viewers to follow at least six storylines whether they want to or not. In other words, we’ve now reached the A/B/C/D/E/F portion of Year 2’s narrative journey, making the returns on our investments of time, energy, and good cheer dubious, to say the least.

Certain questions—chief among them how Wells’s presence serves Picard Season 2’s dramatic ends—inevitably arise. What may strike impatient viewers as pure plot contrivance—namely, delaying Picard’s attempt to preserve the Europa Mission’s launch just long enough to permit Season 2’s antagonists to regroup and hatch their own plan to foil Jean-Luc’s mission—sounds a thematic chord that harmonizes, however tenuously, with Picard’s personal rectitude. The good admiral convinces Wells that he (Picard) and Guinan aren’t threats to 2024 America’s national security by holding fast to the moral principles that’ve characterized his Starfleet career: compassion, honesty, and even empathy. Deceit and trickery cannot help Picard free himself and Guinan from FBI custody, so he pursues the path we’ve seen him travel in hundreds of earlier television episodes and four movies: He tells the truth.

Patrick Stewart is particularly good at conveying Picard’s paternal-without-being-paternalistic concern for Wells in the scene where Picard reveals that Wells’s forest meeting with the Vulcans was, indeed, real. When Wells mentions that the pointy-eared man he saw that night tried to “pull my eyeballs out” after placing his hand on Young Martin’s face (Wells even shudders when describing the sensation of alien fingers “going into—through my skin”), Picard realizes that the Vulcans began mind-melding with Young Martin, but couldn’t finish the process (of erasing the boy’s memories) before an orbiting survey ship beamed them aboard.

Picard, by connecting with Wells intellectually and emotionally, helps the agent understand that his life-changing meeting in the woods was, in fact, a chance encounter with benevolent extraterrestrials, not the fearful confrontation Wells remembers. However far-fetched a federal agent believing this explanation may be, Picard’s choice to treat Wells as an equal partner who deserves the truth is perhaps the Trekiest turn “Mercy” could take. Stewart and Karnes’s authentic interaction helps sell this scene’s emotionally resonant undercurrents even if the glint in Stewart’s eye when Picard asks for Wells’s assistance communicates the actor’s awareness of just how improbable this whole situation is.

What’re the odds, after all, that Picard gets arrested by the one government agent who, while still a child, meets peaceful off-world aliens in the woods (à la Henry Thomas’s Elliott Taylor in Steven Spielberg’s gentle 1982 fable E.T. the Extra-Terrestrial) and who then happens to work his way into a position of authority that not only allows him to monitor surveillance footage of metropolitan Los Angeles but also puts him in the right place at the right time to catch a visitor from another world (or, in Picard’s case, from another century) who, by appearing on a city street out of thin air, happily justifies this same agent’s beleaguered lifelong quest to prove that he’s not cracked or eccentric or crazy, no siree, he’s been right all along about aliens walking amongst us? How lucky can one Starfleet admiral, who just happens to be trying to restore history’s proper course, get?

If Stewart can’t deny this storyline’s too-good-to-be-true conveniences, then Appel, Beyer, and Matalas can’t expect their audience to ignore its manifest implausibilities. Careening from place to place, incident to incident, and tone to tone this way makes “Mercy” too-clever-by-half yet, in the end, oddly absorbing to watch. No matter how unserious Episode 8 gets, its cast’s excellent work buttresses material that, while not exactly flimsy, rests on shaky foundations that somehow remain upright as “Mercy” rotates through its B, C, D, E, and F subplots before concluding with a wallop. “Mercy,” put another way, isn’t finished with us, not by a long shot, thanks to the strangely compelling power of Season 2’s strangest episode yet.

4. Queens & Quarrels

Cindy Appel and Kirsten Beyer run nearly all of Picard’s characters (excepting Orla Brady’s Tallinn and Penelope Mitchell’s Renée Picard) through their paces by intensifying Episodes 6’s and 7’s staccato tempos to frenetic levels rarely seen this season (or, for that matter, last season). Raffi Musiker (Michelle Hurd) and Seven of Nine (Jeri Ryan) get more to do in “Mercy” as they continue tracking the Borg Queen-possessed Agnes Jurati (Alison Pill) to a bar named Deacon’s where, as seen in Episode 7, Jurati ogles the male patrons before breaking the establishment’s plate-glass window to energize the endorphins that allow the Queen to control Jurati’s body.

This locale is yet another 12 Monkeys allusion. Deacon, as fans of that program well know, is the ruthless scavenger-gang leader played by Todd Stashwick throughout its four seasons, so naming a seedy bar after this character is not merely an Easter egg, but a well-placed joke. After questioning the bar’s owner (Oscar Torre) about Agnes’s behavior, Seven realizes that the Queen is strengthening her hold on Jurati. Seven and Raffi then discover the corpse of a red-bearded man (Cyrus Zoghi) murdered by the Jurati Queen when she tries, but fails, to link minds with him, discovering to her dismay that she cannot yet form a new Borg Collective.

Seven and Raffi soon encounter Agnes in a nearby parking lot ingesting lithium ions from car batteries that she rips open with her bare hands. Hoping to stabilize the Borg nanoprobes in her bloodstream, the Jurati Queen doesn’t take kindly to being interrupted, so, in a flash of colorful action, she runs atop the vehicles’ trunks to knock Seven aside before grabbing Raffi by the throat, lifting her into the air, and trying to crush her windpipe.

This brief sequence, nicely staged by the stunt team, is gripping to watch. Only when Agnes’s inner voice screams “No!” does the Queen release Raffi to leave both women gasping for breath. Yet would you believe that, just before this attack, Seven and Raffi’s romantic tensions rise to the surface? Would you accept that Seven, tired of Raffi’s jokes about Seven’s many insights into the Borg Queen’s motives, lets her girlfriend have it? Would you buy that Seven’s accusations so sting Raffi that the surprised pain in Michelle Hurd’s eyes wordlessly concedes how genuine is Raffi’s inability, if not outright refusal, to commit fully to the people she most loves?

I know I do. Plumbing Seven and Raffi’s private difficulties echoes the Jurati Queen’s frustrated desire for intimate connection, which drives her efforts to re-create the Borg Collective and achieve what her friends already have. These good character beats unfortunately receive scant room to develop because, once again, the plot’s forward momentum forces Seven and Raffi to continue hunting for Agnes before she becomes capable of assimilating 21st-Century humanity. Jeri Ryan and Michelle Hurd are marvelous, but a moment’s all they receive to make their spat seem natural when, in fact, Cindy Appel and Kirsten Beyer force it into their teleplay (and this scene). If “Mercy” must acknowledge Seven and Raffi’s burgeoning relationship, then Appel and Beyer’s attitude seems to be: “Well, what the hell, why not here?”

The cast is talented enough to divert some, but not all, attention away from these narrative seams, which are fissures that reveal a simple truth about this installment’s story: “Mercy,” like Season 2, is overpacked. That’s hardly the worst sin for Star Trek: Picard to commit, but devoting so much time to Martin Wells forces three of the show’s best performers (and their characters)—all women who command the screen just as well as Jay Karnes—to take backseats to a guest actor when they should be driving the train, not tagging along for the ride.

Matalas and his collaborators have more story to tell than room to tell it, a common-enough problem in serialized fiction (just ask Charles Dickens, Herman Melville, Ann Radcliffe, and Stephen King), but Picard’s writers should’ve better managed and massaged their material to fit the available space. And yet, despite these criticisms, my disappointment shouldn’t be mistaken for condemnation because “Mercy” includes three additional sequences that nearly redeem its blunders.

Nearly, I hasten to add, nearly, but not quite.

5. Odds & Ends (& Odds)

The first two see John de Lancie’s fabulous Q blast back onto the screen. Q’s waning power doesn’t affect his cleverness or his ability to insert an avatar of himself into Adam Soong’s (Brent Spiner’s) laboratory computer system. Q then gifts Adam’s daughter Koré (Isa Briones)—who discovered in Episode 6 that she’s the last of dozens of clones that Adam unethically created in a failed “somatic nuclear-cell transfer” experiment—medication that treats the genetic disorder trapping her inside her father’s house. Q, in Episode 5 (“Fly Me to the Moon”), uses a temporary version of this remedy to manipulate Adam into killing—or trying to kill—Renée Picard, but Adam’s failure to achieve this objective leads Q to award Koré the permanent cure.

When Koré confronts Adam about his cruelty in creating and confining her, Brent Spiner plays Adam’s venomous anger so well that the man’s utter narcissism comes to the fore. By inflecting Adam’s venality with a bit of Arik Soong’s arrogance (as chronicled in the Enterprise three-parter “Borderland” / “Cold Station 12” / “The Augments”) and a dash of the android Lore’s petulance (as seen in four Next Generation episodes), Spiner’s talent at playing different members of the Soong family has no visible limit (and, it would seem, no foreseeable end).

Isa Briones matches Spiner blow for blow by letting Koré’s disappointment seep into her eyes and voice, yet not override her character’s dignity. Q’s cure permits Koré to exit Adam’s house, walk freely in the sunlight, and tell him not to follow her, leaving Adam shocked by Koré’s departure. This scene crackles with suppressed rage and filial resentment, with Joe Menendez, Isa Briones, and Brent Spiner cooperating beautifully to bring Appel’s and Beyer’s words to life.

Q’s second appearance finds him dressed as an FBI agent who confronts Young Guinan when he discovers her in a separate interrogation room. Q’s surprise turns to derision when he realizes that, whether in their original timeline or the alternate reality they now inhabit, he and Guinan haven’t met in the year 2024. Q is upset that, near the end of Episode 7, Young Guinan employs “a sacred ritual” to summon him for what seems the unworthy task of freeing Picard and herself from arrest in “Mercy.” Guinan turns the tables on Q by sensing a great emptiness that suggests he’s dying. Q replies that he’s “on the threshold of the unknowable” before expressing his surprise, his regrets, and his hopes for redemption in a speech so fiercely, searchingly, and touchingly delivered by John de Lancie that it becomes, in a word, wonderful.

No slouch herself, Ito Aghayere equals de Lancie’s intensity while bringing the same ethereal wisdom to Young Guinan that Whoopi Goldberg imbues into this character’s older incarnation. Considering how electric their scenes in The Next Generation’s “Q Who” and “Deja Q” are, my only regret here is that we don’t get to enjoy Goldberg and de Lancie sharing the screen one last time. Alas, what a pity that, no matter how wonky Picard Season 2’s time-travel mechanics may be, they’re not wobbly enough to ensure this reunion.

Even so, Q and Young Guinan’s fine colloquy can’t quite prepare us—or, at least, me—for the concluding sequence Appel and Beyer cook up for “Mercy.” The Jurati Queen makes her way to Adam Soong’s home laboratory, where she finds Adam drowning his sorrows in booze. Agnes promises to make Adam “the father of the future” if he’ll use his political influence to help her eliminate Picard and his La Sirena crewmates. Adam obliges by calling a friendly Army general to secure a squad of ex-Special Forces soldiers (working as private mercenaries for—12 Monkeys alert!—Spearhead Operations) that’ll commandeer La Sirena for the Queen.

When one mercenary (Charles Maceo) wonders about their mission, the Jurati Queen tells him, “Don’t worry. It only stings for a moment.” Alison Pill speaks these lines in the same seductive tone that Annie Wersching employs in earlier episodes before touching the man’s face and injecting Borg nanoprobes that seize control of his body. Adam watches in horrified surprise as she passes out of frame and asks, in a sweetly mocking voice, “Who’s in the mood to add a little of their biological and technological distinctiveness to our own?” as the sound effect (a computerized sizzle) of the Queen touching every other solider reveals she’s developed the capacity to assimilate humanity centuries before any defense exists.

“Mercy” ends here, on a smashing cliffhanger that guarantees we’ll keep watching. The journey to reach this whopping-good conclusion hasn’t been steady, but closing so strongly gives “Mercy” a sense of purpose that, even if it can’t redeem every imperfection we’ve noted, at least gives Season 2 a swift kick in the pants.

Good enough, I say, good enough—and, yet, not good enough.

“Mercy” is at once frustrating, fascinating, flawed, and fine, so let’s hope Star Trek: Picard resolves its paradoxes—narrative if not temporal—during Episode 9 (“Hide and Seek”) so that the program can barrel into Episode 10’s finale (“Farewell”) just as confidently as it exploded out of Year 2’s starting gate.