Note to The Vestibule’s subscribers: This essay first appeared on Medium on 10 August 2020, but was researched and written during the spring months of 2019.

Although originally intended for Washington University’s The Common Reader: A Journal of the Essay, this publication’s redoubtable editor, Dr. Gerald Early, thought that my piece, while good, not only exceeded TCR’s word limit for feature articles but also was too thorough to whittle down to his preferred length.

After posting my article “Mind Warps: Star Trek’s Holographic Worlds and Mediated Realities” to Medium during 2020’s pandemic lockdowns (at the suggestion of my marvelous girlfriend, Patricia Thomas), I decided to present “Django Unbound” on that platform rather than shopping it to other venues.

Please judge for yourselves whether this article is too long, too short, or just right.

Despite its terrible subject matter, I enjoyed preparing this piece for publication after having several excellent conversations with Tom Maxedon, my friend and then-University of Guam colleague, about America’s enduring cultural fascination with slave dramas, a preoccupation that experienced renewed fervor after the release of Quentin Tarantino’s 2012 film Django Unchained.

I’m happy to say that Tom’s still my friend, although he now works for Phoenix, Arizona’s National Public Radio (NPR) affiliate, KJZZ 91.5 FM.

I’ve divided some long paragraphs into shorter blocks, but haven’t otherwise revised this essay’s text. Please judge for yourselves how wise this decision is/was/may be.

—All the best, Jason

1. Prime Time for Slavery

In December 2012, Quentin Tarantino’s movie Django Unchained opened to rave reviews and sustained controversy. Eleven months later, in November 2013, Steve McQueen’s cinematic adaptation of Solomon Northup’s memoir Twelve Years a Slave (titled 12 Years a Slave to help distinguish film from book) gobsmacked moviegoers with its brutal and—some observers argued—brutalizing depiction of American slavery.

The fact that, in less than the span of a single year, two such notable motion pictures dared dramatize what nineteenth-century Americans called “the peculiar institution” signaled—depending upon whom one asked—that the United States had either reached a new cultural understanding of one of the nation’s original founding sins (with the attempted genocide against Native Americans still awaiting similar filmic treatment) or yet more evidence that the country would never fully face its loathsome past.

As 2020 unfolds, the purported sea change in American attitudes toward slavery heralded by Django Unchained and 12 Years a Slave (only seven years ago, if one can believe it) seems illusory, even delusory. White supremacy — undisguised, prideful, and appalling — has ascended to the Oval Office, while the racist rally held in Charlottesville, Virginia on 11 & 12 August 2017 (dubbed the “Unite the Right” rally, but nothing less than a wretched display of Nazi, Ku Klux Klan, and neo-fascist hatemongering that caused the death of Heather Heyer, among several other injuries), demonstrates that any cultural advances made by Tarantino’s and McQueen’s films were, in the end, provisional.

Even so, cinematic and televisual depictions of slavery have, in the wake of Django Unchained and 12 Years a Slave, expanded—both in scope and sophistication. This statement should not suggest that Tarantino and McQueen directed bad movies (12 Years a Slave remains a masterpiece), but acknowledges that, in the intervening years, new additions to the genre have appeared more frequently, particularly on television, with 2016 being a banner year, if not an annus mirabilis, for the once-again prominent (and ever-growing) genre of slave drama (especially movies and television series depicting the trans-Atlantic slave trade and its aftermath).

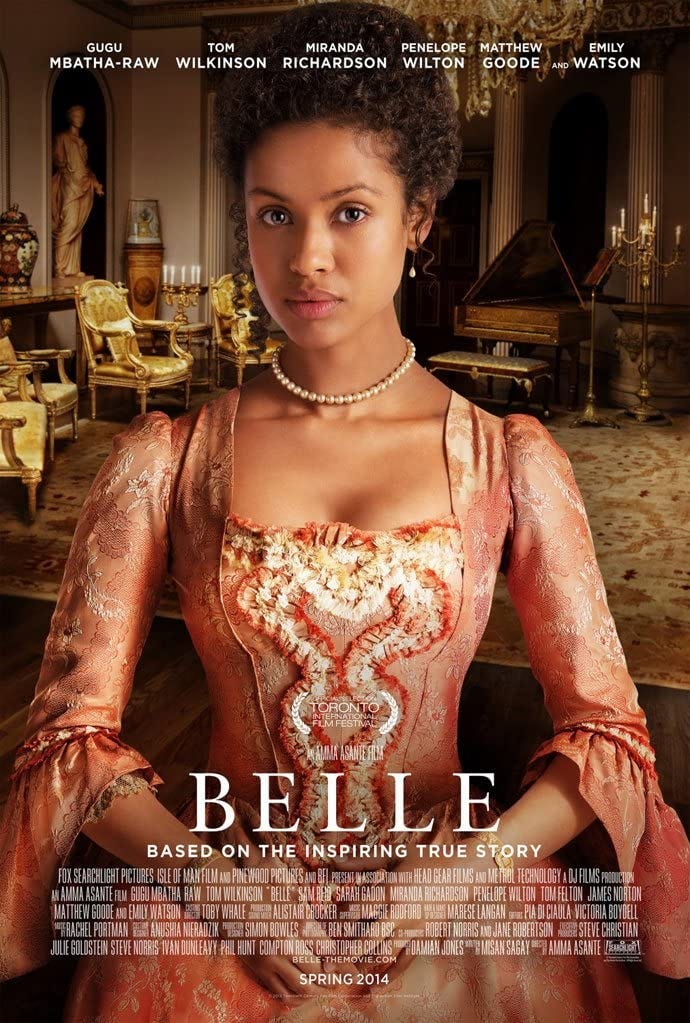

Consider this incomplete list of theatrical films (some—perhaps most—unknown to casual viewers), all released in the half decade after Django Unchained and 12 Years a Slave: Belle (2013, written by Misan Sagay and directed by Amma Asante), The Retrieval (2013, written & directed by Chris Eska), Savannah (2013, written by Annette Haywood-Carter & Ken Carter, directed by Haywood-Carter), Freedom (2014, written by Timothy A. Chey & John Senczuk, directed by Peter Cousens), The Keeping Room (2014, written by Julia Hart and directed by Daniel Barber), The Birth of a Nation (2016, written & directed by Nate Parker, story by Parker & Jean McGianni Celestin), and Free State of Jones (2016, written & directed by Gary Ross, from a story by Ross & Leonard Hartman).

Completists may wish to add David Yates’s The Legend of Tarzan (2016), which prominently features nineteenth-century Congolese slavery in its storyline, while the Roman slaves so spectacularly mishandled in Timur Bekmambetov’s 2016 Ben-Hur remake call to mind American chattel slaves (because the film never stops driving this point home, its chariots serving double duty as wheeled sledgehammers). Other observers may insist upon including Lincoln (2012, written by Tony Kushner and directed by Steven Spielberg), which, while never allowing enslaved characters to speak, dramatizes the political maneuverings that President Abraham Lincoln undertook to ensure passage of the Thirteenth Amendment.

Ponder this list of recent televisual depictions: The Book of Negroes (2015, 6 episodes, created by Lawrence Hill & Clement Virgo), Mercy Street (2016–2017, 12 episodes, created by Lisa Q. Wolfinger & David Zabel), Roots (2016, 4 episodes, adapted from Alex Haley’s Roots: The Saga of an American Family), and—perhaps most prominently—Underground (2016–2017, 20 episodes, created by Misha Green & Joe Pokaski).

We might include Copper (2012–2013, 23 episodes, created by Tom Fontana & Will Rokos) since this series—set in New York City’s Five Points neighborhood—begins in 1864, one year after 1863’s Draft Riots saw working-class white men violently protest conscription into the Union Army in an uprising that quickly turned against free Black Americans. Roots, of course, is a remake of the seminal 1977 television miniseries, executive produced by LeVar Burton himself and quite good on its own terms. And Underground, due to its urgency, superb acting, and wily writing, will launch a thousand dissertations (if it hasn’t already).

These programs’ short runs have not stopped other networks and digital platforms from green-lighting new slave dramas. On the inspiring side of this ledger, Amazon has hired Moonlight screenwriter and director Barry Jenkins to adapt Colson Whitehead’s Pulitzer Prize-winning 2016 novel The Underground Railroad into a one-hour drama. On the problematic side, HBO commissioned Game of Thrones showrunners David Benioff and D.B. Weiss to develop a one-hour, alternate-history drama titled Confederate that was set to imagine twenty-first-century America as a place where the Confederacy successfully seceded from the United States, allowing slavery to survive into the present day, until being cancelled in August 2019.

Despite Benioff and Weiss hurriedly publicizing their collaboration with Truth Be Told’s Nichelle Tramble Spellman and Empire’s Malcolm Spellman soon after HBO trumpeted Confederate going into production, this program’s dodgy premise sounded particularly offensive when considering how stupidly Benioff and Weiss treat slavery on Game of Thrones. The only proper response to Confederate’s cancellation is, indeed, profound relief.

Yet the point remains: slave dramas are, to coin a phrase, hot again. Why? What explains this renewed interest in film and television exploring such a deplorable past, with varying degrees of nuance, complication, and accuracy? Were Django Unchained and 12 Years a Slave so profitable that Hollywood’s tendency to replicate unexpected hits went into overdrive? Were they just so good that audiences clamored for more?

Yes, no, and maybe. The explanation involves historical happenstance, cultural longing, and shameless profiteering, to say nothing of overweening artistic ambition. Tarantino’s and McQueen’s films map out territory about slavery indebted to earlier productions, but they also tackle the issue and the institution from new—or at least unusual—angles. These productions do not always succeed, a hardly unexpected outcome given slavery’s overwhelming significance, but they signal just how fractious America remains when confronting one of its two oldest historical monstrosities.

2. South by Southwest

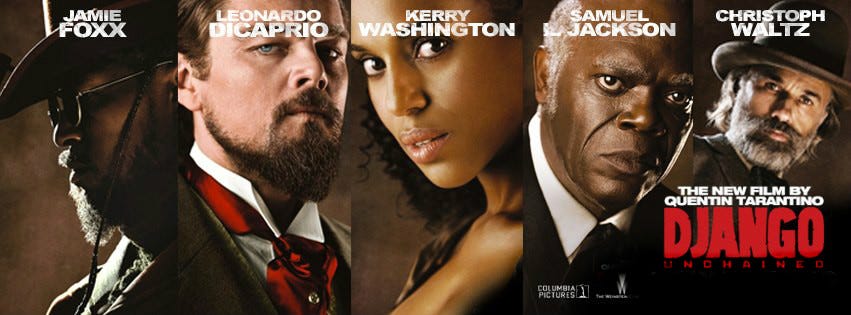

Django Unchained was released to enthusiastic (and occasionally rapturous) reviews, immediate controversy, and awards-season buzz. This last proved durable, since the film won two Academy Awards (for Tarantino’s original screenplay and for Christoph Waltz’s supporting performance as Dr. King Schultz). Waltz also won the Golden Globe and British Academy of Film & Television Arts (BAFTA) awards in the same category, while Kerry Washington and Samuel L. Jackson both won NAACP Image Awards (for their respective roles as house slaves Broomhilda von Shaft, Django’s kidnapped wife—and ancestor of blaxploitation icon John Shaft—and Stephen, the personal valet of antagonist Calvin Candie).

Despite these plaudits, Tarantino’s deliriously entertaining movie does not hold up well in the grim light of our new political era, if it ever did. Spike Lee, for one, never bought the hype surrounding Django Unchained, famously proclaiming, in a 21 December 2012 interview with Vibe TV, “I can’t speak on it ’cause I’m not gonna see it. All I’m going to say is it’s disrespectful to my ancestors,” adding, “that’s just me . . . I’m not speaking on behalf of anyone else.”

When this comment provoked bitter recriminations from Tarantino’s fans, Lee took to Twitter on 22 December 2012 to write, “American Slavery Was Not A Sergio Leone Spaghetti Western. It Was A Holocaust. My Ancestors Are Slaves. Stolen From Africa. I Will Honor Them,” thereby re-igniting the public feud between himself and Tarantino that had existed at least since 1997, when Lee criticized Tarantino’s excessive use of “the N-word” in Jackie Brown.

Lee was roundly denounced in some quarters for his refusal even to watch the film, with Tarantino publicly calling Lee a “son of a bitch” at a 2015 press conference in Sao Paulo, Brazil (promoting The Hateful Eight) when asked if he would ever again work with Lee (who directed Tarantino in Lee’s 1996 film Girl 6).

Lee’s suspicions, however, prove well founded even if he can be gently rebuked for making claims about a film he hasn’t seen. Tarantino’s movie is a gloriously enjoyable romp through pre-Civil War Texas, Tennessee, and Mississippi, shot with the director’s signature verve and gonzo energy, featuring terrific performances from its entire principal cast, a wonderful score by Ennio Morricone, and Leonardo DiCaprio (as the aforementioned Calvin Candie) playing the biggest bastard of his career (at least up to that point, and DiCaprio, lest we forget, had played Howard Hughes in Martin Scorsese’s 2004 film The Aviator).

The movie was a big hit with audiences worldwide (Django Unchained remains the highest-grossing film of Tarantino’s career), always polls well in surveys of Tarantino’s best movies, and even begat a fascinating graphic-novel adaptation of Tarantino’s original, uncut screenplay.

The film is also a silly and shallow depiction of American slavery saved by Jamie Foxx’s, Kerry Washington’s, and Samuel L. Jackson’s commitment to wringing fresh nuance and human complication from roles that, on the pages of Tarantino’s script, are little more than empty placeholders for the writer-director’s racial obsessions. Tarantino’s stated aspirations for Django Unchained, made during his 27 April 2007 interview with the Telegraph’s John Hiscock, were lofty despite the director’s professed distaste for grand, noble, and exalted cinema. Tarantino tells Hiscock that he hopes to invent a new genre called “the southern,” meaning a new form of spaghetti Western set in the Deep South, that allows Tarantino to “explore something that hasn’t really been done.”

And what might that be? Nothing less than “movies that deal with America’s horrible past with slavery and stuff but do them like spaghetti westerns, not like big issue movies.” Fine sentiments, perhaps, but Tarantino doesn’t stop here. No, his goal is “to do them like they’re genre films, but they deal with everything that America has never dealt with because it’s ashamed of it, and other countries don’t really deal with because they don’t feel they have a right to. But I can deal with it all right, and I’m the guy to do it. So maybe that’s the next mountain waiting for me.”

My first reaction upon reading these comments in 2007 was stupefaction. My response upon reading them again in 2020 is stupefaction. Tarantino’s sense that issue films—or what used to be called, in the days when Hollywood studios cranked out thirty movies per week, Big Issue Pictures—can become so self righteous, downcast, and depressing that no one willingly endures them is well taken, while his belief that many Americans remain so ashamed of slavery that they prefer not to think or talk about the topic is depressingly accurate.

Yet Quentin Tarantino—Hollywood darling and wunderkind though he may be—declaring that he’s the person to make American cinema finally explore slavery in a way never before accomplished not only ignores the long history of onscreen slave dramas (Roots chief among them) but also implies that Tarantino understands the institution so well that he can push audiences to face its terrible truths by packaging them inside the bloody, shoot-‘em-up thrills for which he’s famous. Tarantino’s casual confidence in his cinematic prowess regarding slavery, moreover, suggests that he is, if not alone, certainly first among peers in forcing a filmic reckoning with the peculiar institution’s awful history.

Tarantino’s correct on one score. Django Unchained is a genre film par excellence—violent, gory, and gleeful in its unabashed annihilation of issue-film pieties. Few lingering shots of human suffering or bondage appear, no noble speeches about freedom and liberty intrude upon the shenanigans, and certainly no acknowledgment that the peculiar institution was a generation-spanning form of systemic terrorism interferes with the fun.

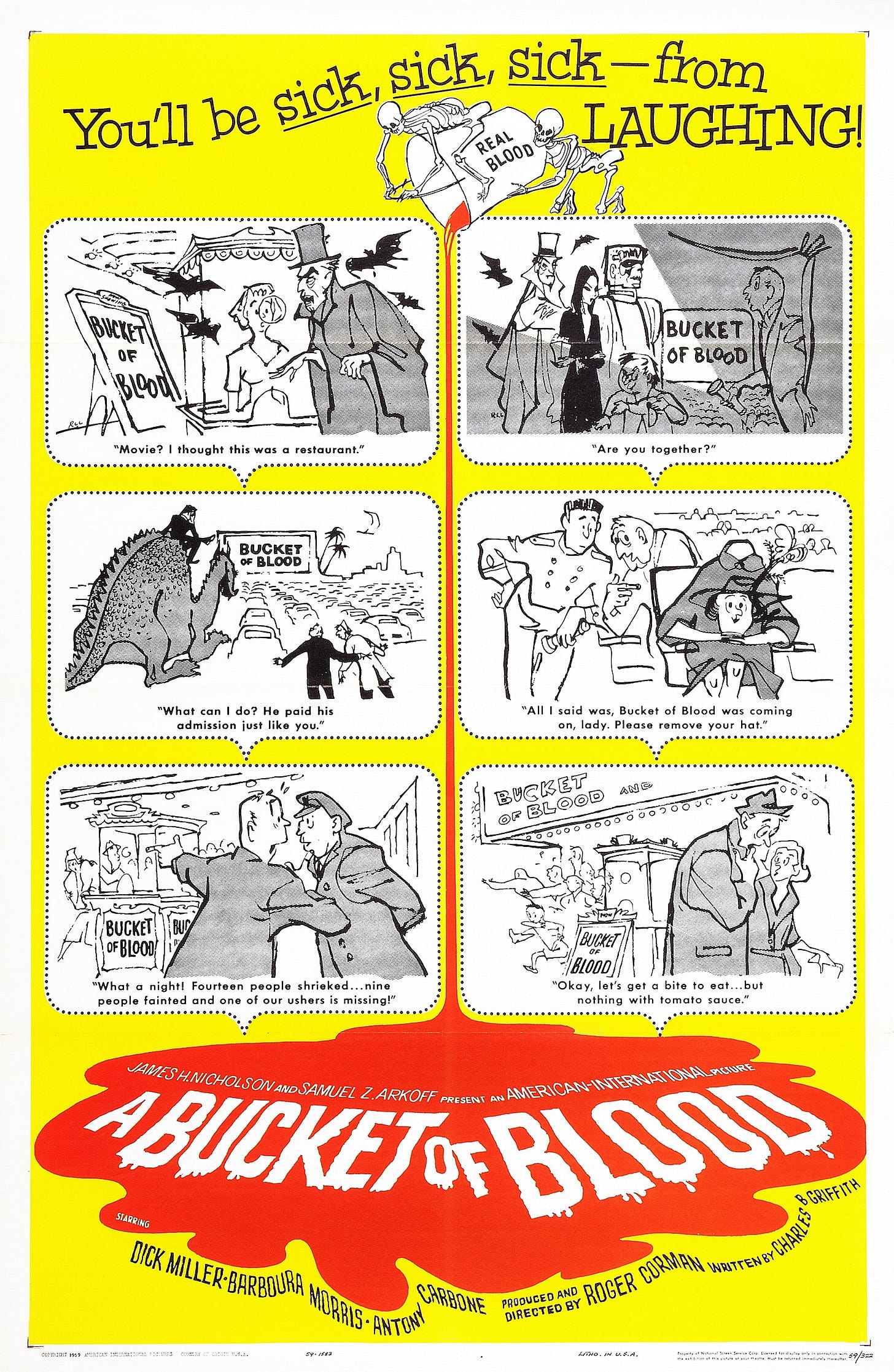

No, it’s all mandingo fights, over-the-top gunplay, and sly dialogue wrapped into perhaps Tarantino’s most unhinged historical revenge fantasy. The movie could easily be retitled Buckets of Blood (in a nod to Roger Corman’s 1959 horror-comedy classic), with its final twenty minutes depicting Django Freeman’s one-man slave rebellion succeeding beyond his (or history’s) wildest dreams, or Inglourious Basterds 2, since it repeats so many beats, attitudes, and character types from Tarantino’s 2009 World War II action extravaganza that Django Unchained serves as a spiritual, if unofficial, sequel/prequel to that movie (this time set in the slaveholding American South rather than Nazi-controlled Europe).

Plus, in the best genre-film fashion, Django Unchained includes one brilliant (and wonderfully satirical) set piece: a group of night riders decides to capture Django and Schultz, who have become a fearsome bounty-hunting team killing slavers throughout the Deep South. These riders, known as the Regulators, pull white hoods over their heads while gathering to strategize about how to catch their hated prey, only to discover that each mask’s eyeholes have been cut in awkward places that prevent the wearer from seeing what’s in front of him.

The ensuing discussion—in which the gang member whose wife made the masks quits the posse in a huff despite his compatriots trying to salve his hurt feelings—hilariously suggests that the men who form the Ku Klux Klan are nothing more than simpering, weak-minded fools unable to get even basic details right. This sequence says more about the stupidity that powers white supremacy, in one go, than the rest of Django Unchained (and, in truth, the rest of Tarantino’s career, save Jackie Brown) combined, although it’s also an historical anachronism: the actual Ku Klux Klan wasn’t founded until after the Confederacy’s defeat in the Civil War, while Django Unchained takes place in 1858, three years before the war begins.

3. Slavery by Any Other Name

Tarantino did not set out to direct a documentary about American slavery, so judging Django Unchained’s historical fidelity may seem a risky, futile, and pedantic proposition until one reads the director’s comments in his 6 December 2012 discussion of the film with BAFTA members, held in London, England.

“We all intellectually ‘know’ the brutality and inhumanity of slavery, but after you do the research it’s no longer intellectual anymore, no longer just historical record—you feel it in your bones,” Tarantino tells his audience. This statement seems unimpeachable, as does his declaration, “It makes you angry, and want to do something.” Then Tarantino himself turns toward accuracy and authenticity by stating, “I’m here to tell you, that however bad things get in the movie, a lot worse shit actually happened.”

Yes, indeed, but here are a few other things that occur in Django Unchained that give the informed viewer pause. When Django and Schultz first arrive at the Tennessee plantation of Spencer “Big Daddy” Bennett (played with Snidely Whiplash glee by Don Johnson), Django meets a slow-talking female slave named Betina (Miriam F. Glover) who embodies every stereotype of Black women that ever appeared in American movies, including those films that Paula J. Massood, in her book Black City Cinema, calls the “plantation idyll” and “antebellum idyll” movies of the 1910s, 1920s, and 1930s.

If this character isn’t bad enough, Django walks with Betina past slaves dressed in their Sunday best, simply out enjoying the lovely day—a few even recline in swings—to suggest that, despite the upsetting inhumanity of slavery that Tarantino emphasizes in his BAFTA talk, its victims at least had the weekend to themselves. Even if Tarantino wishes to demonstrate that not all plantations were as brutal as Calvin Candie’s ironically named Candyland, the director’s choice to include such images as backdrops to his preposterous central storyline undercuts whatever serious points he hopes to make with Django Unchained.

Perhaps most egregiously, the film’s entire plot revolves around Django and Schultz assuming the roles of, respectively, a mandingo scout and a mandingo buyer to infiltrate Candyland in their nonsensical bid to free Broomhilda von Shaft from Calvin Candie’s clutches. The problem here is that, as far as any reputable historian can determine, mandingo fights never occurred in antebellum America.

Aisha Harris, of Slate, queried several experts in December 2012, only to discover that, alas, mandingo matches are almost certainly a cinematic invention that Tarantino embraces so passionately that any moments in Django Unchained that might offer new or unexpected understandings of slavery are ground under the awful, erotically charged spectacle of large Black men beating each other bloody in the film’s version of gladiatorial combat.

Eric Foner never mentions such contests in his many publications about the antebellum era, slavery, and the Civil War. Neither does John Hope Franklin in From Slavery to Freedom: A History of African Americans. No actual slave narrative I know discusses mandingo fighting of the kind portrayed in Django Unchained, even if Frederick Douglass notes in his famous Narrative that the “sports and merriments [like] playing ball, wrestling, [and] running foot-races” that masters encouraged their slaves to participate in during holiday celebrations were among “the most effective means in the hands of the slaveholder in keeping down the spirit of insurrection.”

Aisha Harris, in her Slate article, summarizes David Blight’s thoughts about the matter this way (Blight serves as director of Yale University’s Gilder Lehrman Center for the Study of Slavery, Resistance, and Abolition): “One reason slave owners wouldn’t have pitted their slaves against each other in such a way is strictly economic. Slavery was built upon money, and the fortune to be made for owners was in buying, selling, and working them, not in sending them out to fight at the risk of death.”

Harris also notes that owners did occasionally permit their slaves to fight, but not in death matches, citing Tom Molineaux—the first African-American man to compete for the heavyweight championship in 1809—as a slave who won his freedom fighting another slave in a boxing match that netted Molineaux’s owner $100,000.

Edna Greene Medford, co-editor of The Price of Freedom: Slavery and the Civil War (and then-chair of Howard University’s History Department), tells Max Evry, in his 25 December 2012 MTV piece “Django Unexplained: Was Mandingo Fighting a Real Thing?” that, while she’s discovered rumors of such combat in her research, “there were all sorts of things going on in the South pitting people against one another. To the death, I’ve never encountered anything like that, no. That doesn’t mean that it didn’t happen in some backwater area, but I’ve never seen any evidence of it.”

The most generous-possible reading of Medford’s comments sees Candyland as one of those backwater places that indulged the terrible, whispered practice of gladiatorial slave fights, except for the fact that Candie’s cruelty is known throughout the land, to the point that every character Django and Schultz encounter mentions it.

Candie’s fabled wickedness also provides the movie’s implausible explanation for why Schultz and Django must go to such elaborate lengths—posing as mandingo wranglers for 105 minutes of Django Unchained’s 165-minute running time—to free Broomhilda from Candie’s control rather than simply killing everyone they can after arriving at Candyland, which is no riskier a proposition than continuing their subterfuge (and which Django ends up doing anyway).

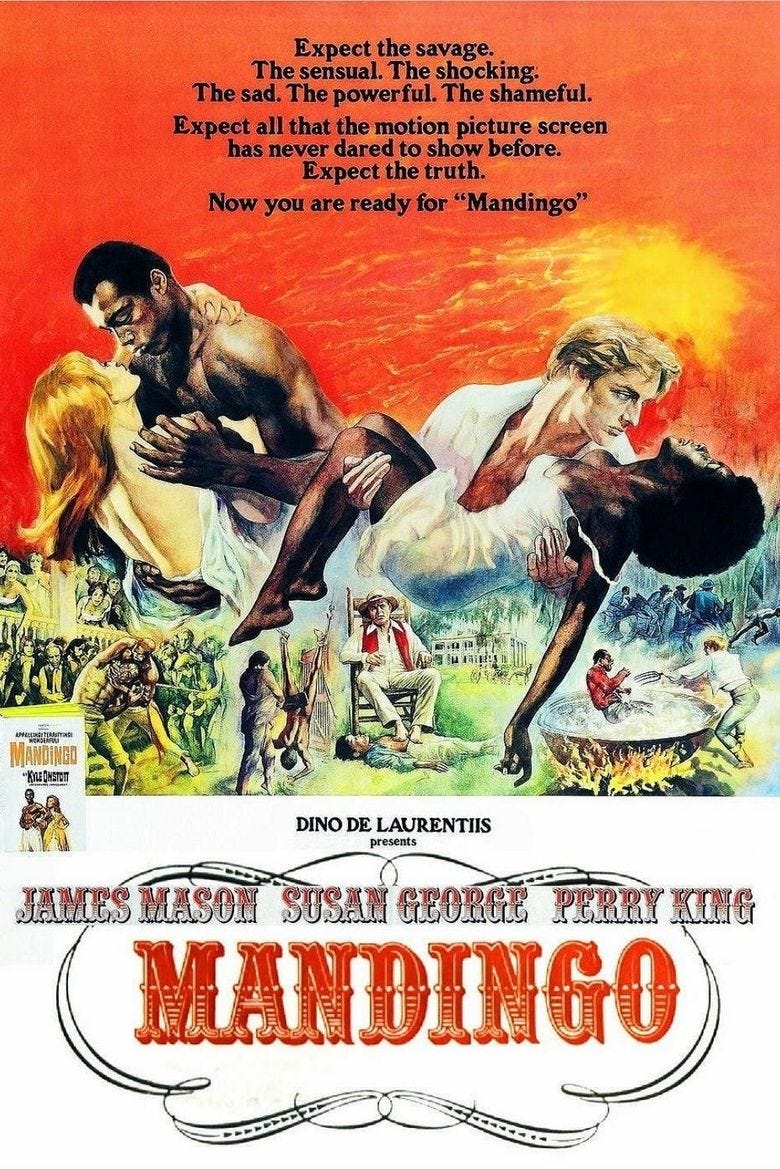

No, the real explanation is that Mandingo, the 1975 exploitation film directed by Richard Fleischer and starring Ken Norton as a fighting slave named Mede, is one of Tarantino’s favorite movies.

All the elaborate analyses of Django Unchained, to say nothing of the many apologias for its supposedly fresh approach to American slavery—and they are now legion, with an entire issue of the academic journal Safundi and Oliver C. Speck’s scholarly anthology Quentin Tarantino’s “Django Unchained”: The Continuation of Metacinema both devoted to parsing Tarantino’s film—come not exactly to naught, but up against the pedestrian reality that Tarantino, like too many Hollywood directors, only claims concern for historical accuracy and period authenticity when necessary, but, in truth, doesn’t care (or, as we intellectuals prefer to say, doesn’t give a shit) so long as these issues don’t interfere with ticket sales or his rights as an artist to embellish history however he wants.

Fair enough, but Tarantino and his admirers can’t have it all ways. Tarantino decided to make an exploitation film featuring slavery because he makes exploitation films, not because he makes slave epics. And yes, Tarantino’s lovingly and dizzyingly crafted exploitation films can entertain, move, and even make their viewers think. Jackie Brown, Pulp Fiction, and Kill Bill amply demonstrate this claim. Plus, not all serious or significant movies need be somber and sober affairs, while it’s also true that too many productions dismissed as exploitation films and “genre movies” (translation: trash) tackle relevant subjects from thoughtful angles.

Django Unchained is not among them.

Is it well made? Yes, tremendously so.

Does it feature good performances? Yes, with at least one effort so terrific that it should have won every acting award available.

Samuel L. Jackson makes his deplorable stock character (the house slave smart enough to run the show from the shadows, but who plays the role of obsequious—if irascible—servant when necessary) so fascinating that viewers may miss the fact that Tarantino, in creating Stephen, rips off wholesale the central premise of Susan Harris’s 1979–1986 sitcom Benson (starring another terrific actor, Robert Guillaume, in the role of a Black man who manages the professional and personal lives of his clueless white boss, in this case the governor of an unnamed state).

Does Django Unchained capture its audience’s attention? Yes, it holds my interest during every viewing (six, at last count).

Is it a great film about slavery? No.

Is it a great film? No, although it wishes to be.

Yet Django Unchained did unplug a cinematic and televisual bottleneck that we were not aware existed by helping to make slavery a topic that subsequent filmmakers and television creators could mine more expertly than Quentin Tarantino.

Does this statement damn Tarantino (and his movie) with faint praise? Yes, but that’s the best I can do for Django Unchained.

4. Yearlings

Steve McQueen’s 12 Years a Slave was released to fawning reviews and awards-season rumors one year (in actuality, 11 months) after Tarantino’s movie. This last proved even more durable than Django Unchained’s haul, with 12 Years a Slave winning the Academy Awards for Best Picture, Best Adapted Screenplay (for John Ridley’s reworking of Solomon Northup’s harrowing slave narrative), and Best Supporting Actress (for Lupita Nyong’o’s remarkable performance as field slave Patsey).

It also won Best Picture from no less than 25 other organizations: the American Association of Retired Persons (AARP), the African-American Film Critics Association, the Alliance of Woman Film Journalists, the American Black Film Festival, the Black Reel Awards, the Boston Society of Film Critics, the BAFTAs, the Broadcast Film Critics Association, the Chicago Film Critics Association, the Dallas-Fort Worth Film Critics Association, the Florida Film Critics Association, the Gay and Lesbian Entertainment Critics Association, the Golden Globes, the London Film Critics Association, the NAACP Image Awards, and on and on (and on).

McQueen won several Best Director awards from film societies and from the NAACP, although he lost the Academy, BAFTA, and Golden Globe awards to Alfonso Cuarón (for Gravity). Nyong’o won prizes from nearly every film organization and association that nominated her for playing Patsey, with 30 such honors listed on her official Facebook page. Ridley also secured as many as 18 awards for his screenplay, although reports that he declined McQueen’s request for co-writing credit provoked rumors of acrimony between the two men that persist to this day.

No matter, because the point is clear: 12 Years a Slave become an awards-season darling, which is enough for savvy readers to suspect that, in the end, it is not so much a good film as a movie that is “good for us.” Such doubt damns 12 Years a Slave with less-than-faint praise, amounting to the cinematic equivalent of being told to eat our vegetables (when we’d prefer the ice-cream satisfactions of fun—or certainly less-stodgy—movies like, say, Django Unchained).

But 12 Years a Slave defies these understandable reservations. McQueen’s movie is, by turns, gripping, horrifying, moving, inspiring, and entirely too much to process in a single screening. The only other two films to affect audiences in the visceral, immediate way that 12 Years a Slave did during my three theatrical viewings of it are Steven Spielberg’s Schindler’s List (1993) and Mel Gibson’s The Passion of the Christ (2004). McQueen and his collaborators could have patented the phrase “not a dry eye in the house,” but their film rarely—if ever—seems manipulative, due in part to McQueen’s assured direction and Ridley’s crackerjack script, but in even larger part to the splendid performances by (among many, many others) Nyong’o, Michael Fassbender as plantation owner Edwin Epps, and Chiwetel Ejiofor in the lead role of Solomon Northup.

Ejiofor—one of the world’s great working actors—generally receives too little credit for 12 Years a Slave’s success despite disappearing into his part so completely that it’s possible to forget he’s acting. Ejiofor’s refusal to employ the flamboyantly painful tricks that characterize awards-bait performances—Al Pacino’s passable turn in Scent of a Woman (1992) and Sean Penn’s execrable emoting in I Am Sam (2001) leap to mind—favorably compares to the great Avery Brooks’s outstanding work as Northup in Gordon Parks’s unjustifiably overlooked 1984 PBS television film Solomon Northup’s Odyssey, a viewing experience unforgettable to anyone who’s ever seen it.

Ejiofor, McQueen, and Ridley know that the incidents documented in Northup’s slave narrative need no goosing from the filmmakers to have profound effects on their audience. To describe 12 Years a Slave as a terrific time at the movies sounds strange, implausible, and even wrongheaded given the terrible events that it dramatizes. And yet, after eight screenings, I find myself helpless to resist its ability to burrow inside my thoughts, my feelings, and my resistance to watching the human degradation of its Black characters.

5. Blood and Guts

“Blood is everywhere in Twelve Years a Slave,” writes Ira Berlin, author of Many Thousands Gone: The First Two Centuries of Slavery in North America, in his introduction to the Penguin Classics reissue (first published in 2012) of Northup’s 1853 slave memoir. The only proper response to this insight is, “Is it ever!” And blood—or the threat of its letting—is everywhere in McQueen’s adaptation, even when no one is being whipped, beaten, or otherwise abused.

The unease that the film evokes in its audience cannot compare to what enslaved Africans suffered, with Northup cataloguing this emotional disequilibrium many times in Twelve Years a Slave, perhaps nowhere more affectingly than when describing how he, a free Black man, is lured into bondage. Northup, famous for his mastery of the violin in his home village of Saratoga Springs, New York, inadvisably accepts, in March 1841, a commission to join the circus company of two men who give their names as Merrill Brown and Abram Hamilton. They promise Northup good wages and an all-expenses-paid trip if he plays at various entertainments that, after a brief stop in New York City, they have scheduled in Washington, D.C.

Northup buys this con job with little forethought, stating, “I at once accepted the tempting offer, both for the reward it promised, and from a desire to visit the metropolis. They were anxious to leave immediately. Thinking my absence would be brief, I did not deem it necessary to write to Anne”—Solomon’s wife—“whither I had gone.” Northup then tours the capital city with his new employers, accepts drinks from them in various saloons, and passes out later that evening despite his determination not to become intoxicated.

He awakes in chains before being transferred to a slave pen that resembles “a farmer’s barnyard in most respects, save it was so constructed that the outside world could never see the human cattle that were herded there.”

Northup concludes this appalling scene with the comment, “Strange as it may seem, within plain sight of this same house, looking down from its commanding height upon it, was the Capitol. The voices of patriotic representatives boasting of freedom and equality, and the rattling of the poor slave’s chains, almost commingled. A slave pen within the very shadow of the Capitol!”

This passage gives John Ridley and Steve McQueen their first opportunity to demonstrate how well their movie can adapt Northup’s memoir. The sight of Chiwetel Ejiofor, as Northup, struggling against his chains and being beaten by his captors is affecting enough thanks to Ejiofor’s deft performance—his face moves from confusion to anger to pain to horror in three minutes—but the camera then rises to see the United States Capitol Building in the distance, driving home the peculiar institution’s inhumane hypocrisy better than even Northup’s words in a scene that establishes just how good—and how difficult—12 Years a Slave is to watch.

McQueen’s movie may strike viewers attuned to the elemental thrills of Django Unchained as precisely the type of production that Quentin Tarantino hoped to avoid: an issue film that includes all the pieties of its genre, from somber shots of human bondage’s suffering to noble reflections about the necessity of freedom in a world so unfair that the viewer can scarcely believe it ever existed. Indeed, 12 Years a Slave may seem to be exactly what its detractors—critic Armond White foremost among them—claim: an Oscar-baiting movie that announces, in every frame, its status as a Very Important Film with Serious Statements to make about Significant Topics or, in simpler parlance, an exercise in dehumanizing drudgery.

White’s typically contrarian review, first published on CityArts magazine’s website, is unsparing. “Brutality, violence, and misery get confused with history in 12 Years a Slave,” he writes, claiming that, “for McQueen, cruelty is the juicy-arty part; it continues the filmmaker’s interest in sado-masochistic display, highlighted in his previous features Hunger and Shame.”

Not to be deterred, White then proclaims 12 Years a Slave to be the opposite of a masterpiece: “Depicting slavery as a horror show, McQueen has made the most unpleasant American movie since William Friedkin’s 1973 The Exorcist. That’s right, 12 Years a Slave belongs to the torture porn genre with Hostel, The Human Centipede and the Saw franchise but it is being sold (and mistaken) as part of the recent spate of movies that pretend ‘a conversation about race.’”

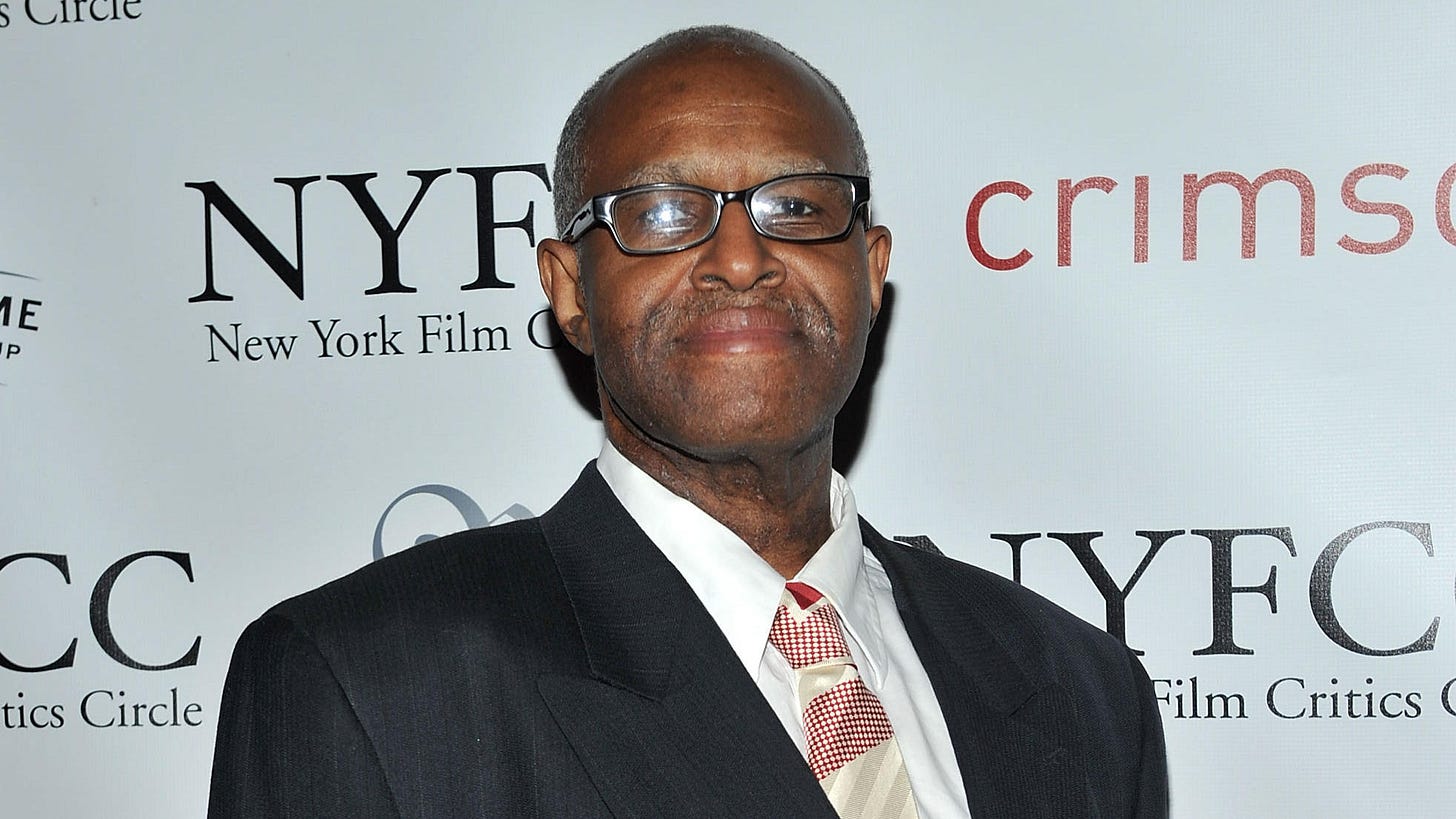

White, no matter how much one sympathizes with his against-the-grain tendencies, is wrong on nearly every point. This judgment isn’t a full dismissal, since White draws our attention to just how much onscreen cruelty McQueen and Ridley include in 12 Years a Slave, while the controversy that engulfed White when he was expelled from the New York Film Critics Circle for allegedly calling McQueen “an embarrassing doorman and garbage man” at the 79th Annual New York Film Critics Circle Awards in January 2014 cannot erase from mind the many shots of Black human flesh—Northup’s and Patsey’s foremost among them—whipped, beaten, abused, and scarred in 12 Years a Slave.

Patsey’s treatment remains so disturbing that I sympathize with viewers who avert their eyes when plantation owner Edwin Epps berates, rapes, and tortures her. More to the point, I understand why fellow audience members, at every screening I attended, exited the theater when Epps violently rapes Patsey in a scene that qualifies as a horror movie unto itself.

Michael Fassbender, as Epps, is so frighteningly pathetic—sweating all over Patsey, pleading for her approval, and bellowing in anger when he doesn’t get it—that the actor seems to channel his real-life character’s rage from beyond the grave. Even more viewers fled the theatre when Epps, in the film’s most famous sequence, forces Northup (known as Platt) to whip Patsey’s naked body, becoming so enraged at Solomon’s halfhearted efforts that, egged on by Mistress Epps (Sarah Paulson), Edwin grabs the whip. He so severely lashes Patsey that Northup cannot watch.

Solomon bends over while Epps strikes Patsey with such force that her back splits open. McQueen never cuts away, but employs a single shot to force the audience to watch Patsey’s abuse. This display was (and is) so difficult to endure that I—along with everyone who remained—openly and profusely wept.

Even writing about this scene makes me well up, so McQueen accomplishes precisely what he and Ridley intended, with Ridley’s screenplay including near-verbatim passages from Twelve Years a Slave. “He [Epps] then seized it [the whip] himself,” Northup writes, “and applied it with ten-fold greater force than I had. The painful cries and shrieks of the tortured Patsey, mingling with the loud and angry curses of Epps, loaded the air. She was terribly lacerated—I may say, without exaggeration, literally flayed. The lash was wet with blood, which flowed down her sides and dropped upon the ground.”

Again, it seems wrong to compliment Nyong’o’s and Fassbender’s performances, to say nothing of the makeup team’s efforts, for so expertly transferring Northup’s words to the screen, but this scene remains so shocking, both in its power and its placement late in the film, that Armond White’s dismissal of McQueen’s movie as torture porn is perverse.

But 12 Years a Slave is not. McQueen directs Patsey’s flagellation to recall Kunta Kinte’s (LeVar Burton’s) infamous whipping in the 1977 television adaptation of Alex Haley’s Roots, even if McQueen increases the violence of the lash’s blows and the savagery of the person inflicting them. Kinte eventually proclaims his name to be Toby to avoid more punishment, but Patsey can only weep, in pain and shame, with no lesson learned. McQueen captures human degradation at its most foul, not to celebrate or to romanticize Patsey’s torture, but to demonstrate just how depraved slavery and its adherents were.

Good as Ejiofor and Fassbender are, Lupita Nyong’o’s work here (and throughout 12 Years a Slave) is astonishing. That so new a performer—Nyong’o had only begun serious acting in 2008, four years before the movie’s production—could dig deep enough into the terrible experiences of enslaved women to play Patsey speaks to Nyong’o’s talent, effort, and commitment to the role.

She earned, several times over, the awards she received, and if Nyong’o was underutilized in the years immediately following 12 Years a Slave, her roles as Nakku Harriet in Mira Nair’s Queen of Katwe (2016) and as Nakia in Ryan Coogler’s Black Panther (2018) demonstrate just how good she is.

The fact that Northup escapes bondage, but Patsey and the other slaves cannot, also prevents 12 Years a Slave from descending into the mawkish melodrama that Django Unchained indulges when its protagonist kills his way to freedom. Patsey’s whipping also reverses another revenge-fantasy sequence in Django Unchained that sees the protagonist, dressed in a ridiculous powder-blue costume, stop the whipping of an enslaved woman named Little Jody (Sharon Pierre-Louis) by shooting dead Big John Brittle (M.C. Gainey), the man about to perpetrate Jody’s punishment, before grabbing the lash and whipping John’s brother, Lil Raj Brittle (Cooper Huckabee), to the ground.

Satisfying as this sight may be, 12 Years a Slave cannot indulge such historical illusions because Ridley and McQueen know that Black men, even free Black men, could never have attacked white men in the antebellum South without being immediately arrested or killed. McQueen’s movie, as such, becomes an important corrective to the most ludicrous elements of Tarantino’s, almost as if McQueen intended 12 Years a Slave to reply to Django Unchained’s exaggerations by demonstrating more fidelity to the historical record than Tarantino’s fun, but problematic film.

6. Ins and Outs

This final aspect is important since Django Unchained gives the impression that American chattel slavery could have been strenuously resisted—if not ended—had enslaved Africans (and their descendants) more actively fought for their own liberation. Django’s journey from beaten-down bondsman to badass bounty hunter defies all knowledge of actual American slave rebellions, with Tarantino not knowing or caring that every such revolt—including Nat Turner’s famous uprising—was eventually put down, with its participants killed during the attempt or, if they survived, jailed and then executed.

As Henry Louis Gates, Jr. notes in an important essay about this topic, “one of the most pernicious allegations made against the African-American people was that our slave ancestors were either exceptionally ‘docile’ or ‘content and loyal,’ thus explaining their purported failure to rebel extensively.”

Gates cites Herbert Aptheker’s pioneering study American Negro Slave Revolts, which documents at least 250 such rebellions occurring in America between 1526 and 1860, with Aptheker defining a slave rebellion as an action that saw ten or more slaves take up arms to resist their bondage. Joseph E. Holloway writes on The Slave Rebellion Web Site that at least 313 such slave revolts happened within the pre-Civil War United States, stating, “it is possible to say that enslaved Africans contributed directly to their own liberation by rebelling and participating in insurrectionary activities. The fear of slave rebellion and the need to control slave labor led to the creation of an armed camp situation in the antebellum.”

So, we might conclude, Django’s killing spree in Django Unchained has some historical precedent. Yet its solitary nature—one man against all Candyland’s employees and residents—does not. Slave rebellions were collective actions that frequently erupted from terrible local (and immediate) conditions that provoked their survivors to rise up as one (not as individuals).

Django Unchained never truly acknowledges how overwhelming a system of economic, physical, and psychological brutality slavery was. The armed-camp imagery in Holloway’s essay wasn’t mere metaphor, but a daily reality for enslaved men and women living throughout the Deep South. On this score, 12 Years a Slave is better, although McQueen’s film and Northup’s memoir can only suggest the scale of slavery’s generational terrorism. Perhaps no single text—movie, television series, novel, or history book—can do so, but 12 Years a Slave makes a better case for itself than many other onscreen slave dramas.

And, without fail, more films and television series about slavery are on the way, while some have already arrived in covert form. At least one commentator, Esquire’s Steven Thrasher, proclaims Jordan Peele’s terrific 2017 film Get Out to be “the best movie ever made about American slavery,” although Thrasher, in all fairness, considers the peculiar institution to be “so absurd [that] I had already found Quentin Tarantino’s Django Unchained to be a more effective film at depicting its American-style perversity than Steve McQueen’s stentorian 12 Years a Slave.”

As unhinged spectacle, Django Unchained is perverse, but not in the way Thrasher believes. It’s ultimately an insubstantial movie whose dramatic reach exceeds its grasp. That’s not the worst target for a film as watchable as Django Unchained to set in its sights, but I wish Tarantino had better aim. And stentorian, particularly if we understand this term to mean “loud and powerful,” compliments 12 Years a Slave even if McQueen’s production, in the end, will always seem more stilted than Tarantino’s.

For myself, I cannot think of one without the other. Django Unchained and 12 Years a Slave, thanks to their proximity in subject matter and release date, will always be paired. Tarantino and McQueen are much different directors who find themselves fascinated by pain, blood, and exploitation (whether cinematic or historical).

Tarantino could not have predicted, when formulating Django Unchained in 2007, that his film would be outdone by 12 Years a Slave, an adaptation directed by and starring non-Americans. Tarantino’s belief that people from other countries don’t tackle American slavery because “they don’t feel they have a right to” was an extravagant misjudgment, as is Django Unchained (despite its fascinating—but finally hollow—approach to the peculiar institution). Slave dramas are rarely easy to watch, and perhaps they shouldn’t be.

That notion, no matter how fanciful or aspirational, will not stop us from seeing them. We can only hope that their writers, directors, and producers will dramatize this disgraceful history by excavating its most discomfiting truths—in short, by bringing slavery’s complications to life rather than burying them.

WORKS CONSULTED

12 Years A Slave. Screenplay by John Ridley, from the memoir Twelve Years a Slave by Solomon Northup. Directed by Steve McQueen. Fox Searchlight Pictures, 2013. 134 minutes.

Alexander, Julie. “HBO’s Controversial Confederate Series Is Canceled As Showrunners Ink Netflix Deal.” The Verge, 8 August 2019, https://www.theverge.com/2019/8/8/20791874/confederate-hbo-david-benioff-db-weiss-netflix-game-of-thrones.

Berlin, Ira. “Solomon Northup: A Life and a Message.” Introduction to Twelve Years a Slave, by Northup. Penguin Books, 2012.

Bucket of Blood, A. Written by Charles B. Griffith. Directed by Roger Corman. Alta Vista Productions and American International Pictures, 1959. 66 minutes.

Django Unchained. Written and directed by Quentin Tarantino. Columbia Pictures and The Weinstein Company, 2012. 165 minutes.

Douglass, Frederick. Narrative of the Life of Frederick Douglass, An American Slave & Incidents in the Life of a Slave Girl (by Harriet Jacobs). 1845. Modern Library, 2000.

Evry, Max. “Django Unexplained: Was Mandingo Fighting a Real Thing?” MTV, 25 December 2012, http://www.mtv.com/news/2814256/is-mandingo-fighting-a-real-thing/.

Gates, Jr., Henry Louis. “Did African-American Slaves Rebel?” PBS, http://www.pbs.org/wnet/african-americans-many-rivers-to-cross/history/did-african-american-slaves-rebel/.

Harris, Aisha. “Was There Really ‘Mandingo Fighting,’ Like in Django Unchained?” Slate, 24 December 2012, http://www.slate.com/blogs/browbeat/2012/12/24/django_unchained_mandingo_fighting_were_any_slaves_really_forced_to_fight.html.

Hiscock, John. “Quentin Tarantino: I’m Proud of My Flop.” Telegraph, 27 April 2007, https://www.telegraph.co.uk/culture/film/starsandstories/3664742/Quentin-Tarantino-Im-proud-of-my-flop.html.

Holloway, Joseph E. “Slave Insurrections in the United States: An Overview.” The Slave Rebellion Web Site, http://slaverebellion.info/index.php?page=united-states-insurrections.

Lee, Spike. Twitter, 22 December 2012, https://web.archive.org/web/20130114091533/.

Mandingo. Screenplay by Norman Wexler, from the novel Mandingo by Kyle Onstott and the stage-play adaptation Mandingo by Jack Kirkland. Directed by Richard Fleischer. Dino De Laurentiis Company and Paramount Pictures, 1975. 127 minutes.

Marc, Christopher. “Once Upon a Time in Hollywood Passes Inglourious Basterds to Become Quentin Tarantino’s 2nd Highest-Grossing Film.” HN Entertainment, 16 September 2019, https://hnentertainment.co/once-upon-a-time-in-hollywood-passes-inglourious-basterds-to-become-quentin-tarantinos-2nd-highest-grossing-film/.

Massood, Paula J. Black City Cinema: African American Urban Experiences in Film. Culture and the Moving Image Series, Temple University Press, 2003.

Northup, Solomon. Twelve Years a Slave. 1853. Penguin Books, 2012.

Obenson, Tambay A. “Tarantino Says He’ll Never Work w/ Spike Lee, Calls Him Contemptible + Says He Has 2 More Films Before Retirement.” IndieWire, 23 November 2015, https://web.archive.org/web/20160630060743/http://www.indiewire.com/2015/11/tarantino-says-hell-never-work-w-spike-lee-calls-him-contemptible-says-he-has-2-more-films-before-retirement-135512/.

Platon, Adelle. “Spike Lee Slams Django Unchained: ‘I’m Not Gonna See It.’” Vibe TV, 21 December 2012, https://web.archive.org/web/20151231122952/http://www.vibe.com/2012/12/spike-lee-slams-django-unchained-im-not-gonna-see-it/.

Pulver, Andrew. “Quentin Tarantino Defends Depiction of Slavery in Django Unchained.” Guardian, 7 December 2012, https://www.theguardian.com/film/2012/dec/07/quentin-tarantino-slavery-django-unchained.

Setoodeh, Ramin. “12 Years a Slave Director Steve McQueen Heckled at New York Critics Circle Awards.” Variety, 6 January 2014, http://variety.com/2014/film/news/12-years-a-slave-director-steve-mcqueen-heckled-at-new-york-critics-circle-awards-1201032911/.

Sneider, Jeff. “Oscars: 12 Years a Slave Screenplay Rift Between Steve McQueen, John Ridley Boils Over.” The Wrap, 3 March 2014, https://www.thewrap.com/oscars-steve-mcqueen-john-ridley-quietly-feuding-12-years-slave-screenplay-credit/.

Solomon Northup’s Odyssey. Teleplay by Lou Potter & Samm-Art Williams, from the memoir Twelve Years a Slave by Solomon Northup. Directed by Gordon Parks. American Playhouse, 10 December 1984. 115 minutes.

Stedman, Alex. “Armond White Kicked Out of New York Film Critics Circle.” Variety, 13 January 2014, http://variety.com/2014/film/news/armond-white-kicked-out-of-new-york-film-critics-circle-1201052799/.

Steele, Tanya. “Tarantino’s Candy (Slavery in the White Male Imagination).” Shadow and Act, 27 December 2012, https://shadowandact.com/2012/12/27/tarantinos-candy-slavery-in-the-white-male-imagination/.

Thrasher, Steven. “Why Get Out Is the Best Movie Ever Made about American Slavery.” Esquire, 1 March 2017, https://www.esquire.com/entertainment/movies/a53515/get-out-jordan-peele-slavery/.

Udovitch, Mim. “Tarantino and Juliette.” Quentin Tarantino: Interviews, edited by Gerald Perry, University Press of Mississippi, 1996.

White, Armond. “Dud of the Week: 12 Years a Slave.” New York Film Critics Circle, 16 October 2013, http://www.nyfcc.com/2013/10/3450/.