Note to The Vestibule’s subscribers: This essay first appeared on Medium on 9 August 2020, but was first written three years prior, in early 2017, for a scholarly anthology intended to address the broad topic of “Star Trek and media,” as the original CFP (Call for Papers) stated in its short-but-sweet description of this project.

This collection never saw the light of day. I submitted a proposal to the volume’s editor, who approved it with the proviso that I discuss as many specific examples from the Trek films and television series as possible to provide the broadest-possible range of references for the book’s audience, whom he hoped would include academic specialists, Trek aficionados, science-fiction enthusiasts, and lay readers of all stripes.

After submitting my draft (in late April or early May 2017), the editor informed all contributors that the original publisher (McFarland & Company, if memory serves) wasn’t offering financial terms—for his fee or for other costs—acceptable to him, so he’d cancelled the contract and would attempt to place the book elsewhere.

I certainly understood his reasoning. Although contributors to academic anthologies don’t normally receive payments for their work beyond receiving a free copy of the book, the opportunity to purchase additional copies at a steep discount, the right to place the publication on our CVs (curricula vitae), and the joy we bring our readers, our editor agreed to split all royalties with us.

Academic anthologies rarely make money, but this gesture was both nice and unexpected. As to the volume’s budget, obtaining copyright permission for all cited materials, as well as photographs, can rack up costs in the thousands of dollars (if not more), although scholarly publishers frequently push their authors and editors to eliminate these fees by respecting the boundaries of American copyright law’s “fair use” provisions, by including public-domain (i.e., free) photos whenever possible, and by paying for images out of their own pockets if necessary.

Plus, editing any volume—scholarly or otherwise—is a tremendous task that involves coordinating the submissions of one dozen (or more) cantankerous writers who routinely miss deadlines, who blow off editorial suggestions, who fight changes to their precious prose, and who sometimes act like squalling children whose sandcastles have just been knocked down by the big, bad, bully editor.

It’s a thankless task, so I was pleased when my editor thanked me for submitting my essay on time and for readily agreeing to his minor suggestions. Star Trek: Discovery hadn’t yet premiered, but my editor, expecting it would take him until December 2017 or January 2018 to get the volume’s manuscript into publishable shape, asked me to stand ready to write a short section about this new series for inclusion should the need arise. I presume he asked each of the volume’s 15 contributors to do so, as well.

Discovery “dropped” on CBS All Access (now Paramount+) on 24 September 2017, but my editor, after attempting to place our “Star Trek and media” anthology at other publishers—including Columbia University Press, Oxford University Press, and Syracuse University Press (which nearly funded it, but decided against doing so for reasons I’ll never know), officially declared this project dead in November 2017.

Such is life, particularly in the small-time/small-potatoes game of academic publishing, leaving my manuscript homeless. It languished in my computer’s hard drive, but after pandemic lockdowns began in March 2020, my wonderful girlfriend, Patricia Thomas, suggested that I post this essay to Medium, a publishing platform that’d become home to many writers like myself (i.e, people who’d frequently threatened to start their own websites or blogs, but had never done so).

As always, she was correct. “Mind Warps” remains available on Medium, but now appears here for (what I hope is) your reading pleasure. I’ve broken some long paragraphs into shorter chunks, but otherwise resisted the temptation to revise this essay’s prose (no doubt for better and for worse).

—All the best, Jason

1. Boldly Going into Media History

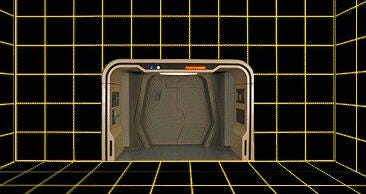

The series finale of Star Trek: Enterprise, appropriately titled “These Are the Voyages…,” uses one of Star Trek’s most fascinating inventions, the holodeck (a computer-controlled room capable of creating interactive environments and characters indistinguishable from reality), to re-create the final mission of Captain Jonathan Archer (Scott Bakula) and his intrepid crew. The fact that this holodeck does not exist in Archer’s time provides only one of the episode’s many intriguing elements for science-fiction (SF) audiences interested in how the genre represents, incorporates, and extrapolates mass media into future contexts.

Archer’s final mission does not play to the series’s audience in the same fashion as all its other episodes, namely as a story solely reserved for and directly communicated to Enterprise’s viewer. “These Are the Voyages…,” rather, unfolds as a holographic simulation playing roughly two hundred years after the fact for the benefit of Commander William Riker (Jonathan Frakes), the first officer of Star Trek: The Next Generation’s Starship Enterprise-D, making the episode a strangely self-reflexive example of American SF television.

Riker consults a holographic replica of Archer’s last adventure to gain insight into a difficult professional quandary that not only has him at odds with his own captain, Jean-Luc Picard (Patrick Stewart), but that also foregrounds the holodeck as Star Trek’s primary contribution to imagining how mass media will evolve as humanity develops ever-more-powerful entertainment technologies.

As the most popular and influential SF television franchise in American history, Star Trek’s consistent fascination with its own existence as commercial entertainment provides an intriguing gloss on how visual media create, disrupt, and reify fictional worlds. The possibilities and the dangers of such world creation are notable parts of Star Trek’s narrative project, making the franchise an important touchstone of 20th- and 21st-Century science fiction’s examination of the design, the development, and the difficulties of media-driven societies.

We cannot understand Star Trek’s holodeck as more potent entertainment than film and television without examining the ambivalence that Star Trek regularly manifests toward these two-dimensional visual media. The fact that the franchise originated in television before migrating to film only complicates our response to Star Trek’s representation, and occasional repudiation, of visual entertainment.

Turning our attention to this topic clears a path to appreciating how holographic environments, fantasies, and characters not only expand the scope, sophistication, and influence of mass media in Star Trek’s imagined future, but also fundamentally alter our understanding of electronic mass media’s power to create fictional worlds that complement and contest one another.

2. Future Worlds, Past Entertainments

The holodeck first appears in the Star Trek franchise in the 1974 Animated Series episode “The Practical Joker” (although Enterprise crew members call it a “recreation room”) before making its inaugural live-action appearance in The Next Generation’s 1987 pilot episode, “Encounter at Farpoint,” as a place that crew members visit when they wish to relax.

Star Trek creator Gene Roddenberry, however, had conceived this invention as early as the original show’s third season. In a 3 April 1968 letter to NBC Program Manager Stanley Robertson, quoted in Herbert F. Solow and Robert H. Justman’s book Inside Star Trek: The Real Story, Roddenberry makes the first known reference to a holodeck:

NBC should keep in mind that our ship, after all, is our “familiar home base” and is as important to the fabric of our show as “BONANZA’s” (sic) house and ranch which has been the locale of a great number of their most exciting episodes. In that regard, to help counteract any “sameness” about the ship, we are presently planning this season the addition of new and interesting ship areas, including a “simulated outdoor recreation area” complete with foliage, turf, running water, and etc. (404)

Roddenberry justifies this simulated recreation area’s inclusion in his series as a method of distinguishing Star Trek from its television contemporaries, as well as an innovation that expands the range and the character of the Enterprise’s technological sophistication. That this early holodeck serves recreational purposes reflects the importance of entertainment in a future world that includes few references to visual mass media. Captain James T. Kirk (William Shatner) and his colleagues do not watch movies or television, do not play computer games (preferring, instead, three-dimensional chess), and do not surf a galactic version of the World Wide Web.

Their most common exposures to art involve stage productions of Shakespeare’s plays (in the episode “The Conscience of the King”), poetry (“Where No Man Has Gone Before”), and music (Communications Officer Uhura [Nichelle Nichols] sings in “Charlie X,” while First Officer Spock [Leonard Nimoy] plays a Vulcan lyre in “Charlie X” and “The Way to Eden”).

The limited forms of mass media found in the original Star Trek are easily explainable when we consider the restrictions and vicissitudes of 1960s weekly television production: 1) The series’s budget—already stretched thin by the demands of creating the Enterprise, the many objects and details of 23rd-Century life, and numerous alien environments—did not allow Star Trek’s creative team the time to mount the elaborate special effects necessary to produce convincing holographic environments; 2) Computer games and the Internet had either yet to be invented or yet to become popular with the American public, and so were not on the cultural landscape during the series’s three-year run; and 3) Star Trek’s debt to Enlightenment philosophy and culture ruled out mass media as artistic forms that its characters might find interesting.

We should also recall that, in the late sixties, the United States had only begun the process of becoming the media-saturated society that 21st-Century observers take for granted. America was, in other words, a far less media-savvy society during the 1960s than even during the late 1980s (to say nothing of 2020).

Although cinema had been the dominant form of visual media during the 1940s and the early 1950s, television had proliferated throughout American households by the time Star Trek premiered in 1966, exposing both adults and children to a variety of visual programming never before imagined. The existence of only three broadcast networks and the Public Broadcasting System may seem paltry by the viewing standards of 21st-Century audiences, who have access to hundreds of digital channels routinely broadcasting thousands of hours of television programming, but the sheer amount of visual entertainment available to 1960s Americans was an unprecedented cultural experience.

Even so, the paucity of mass media in the original Star Trek might seem to constitute a failure of imagination on the part of Roddenberry and his writers, especially when we consider that the series successfully extrapolated, more often than it failed, how propulsion systems, computer technology, political organizations, and human behavior would differ three hundred years into the future.

Philip K. Dick had not only presented numerous (and often negative) examples of mass media in his SF tales of the 1950s and early 1960s (the short stories “The Defenders” [1953] and “The Mold of Yancy” [1955], to say nothing of the novels The Simulacra [1964] and The Penultimate Truth [1964] are good examples), but also predicted the creation of virtual reality in his 1968 novel Do Androids Dream of Electric Sheep? by dramatizing the effects of an invention called the empathy box, which allows its users to enter a collective and interactive illusion created by the minds of all the people plugged into the device’s computer-assisted technological system.

Isaac Asimov, Robert Heinlein, and Arthur C. Clarke, SF writers with whom Roddenberry was quite familiar, had also speculated about how media would evolve in future centuries. A more likely explanation for Star Trek’s resistance to showing 23rd-Century examples of mass media is that Roddenberry and his writers, who may or may not have been aware of the deep suspicions that scholars such as Theodor Adorno and his Frankfurt School compatriots harbored about mass media, were certainly familiar with the common assumption that television was, as FCC Chairman Newton N. Minow had famously proclaimed in a 1961 address to the National Association of Broadcasters, a “vast wasteland” (Minow and LaMay 188).

Roddenberry and his staff therefore excluded mass media from their future world to avoid dealing with the intellectual softness and violent behavior that television was accused of fostering in its viewers (and that would be out of place in Star Trek’s highly educated and peaceful world). This omission also served to demonstrate that Roddenberry’s future human society had developed forms of recreation that had supplanted cinema and television. In a supremely ironic move for television professionals, Roddenberry and his writers downplayed the significance of visual art in the 23rd Century.

As any viewer of the original Star Trek knows, the Enterprise crew does, in fact, watch a version of television. The viewscreen that forms the focus of most bridge scenes allows Kirk, Spock, and their crewmates not only to see what happens outside their ship but also to establish direct visual communication with the inhabitants of other vessels, space stations, and planets.

The immediacy of the resulting interchanges is seductive, vicariously dramatizing the dream of many television watchers to participate in onscreen events. If the original Star Trek viewer had to rely on telephones to converse with friends and family, Kirk and his crew could at last see one another while talking, even over great distances, to develop a far more personal type of dialogue. Television, in this instance, ceases to be entertainment and instead facilitates an intimacy in communication that only the visual image can create. Star Trek, therefore, does not shun television as unworthy of its advanced human society, but rather adapts its conventions for purposes that subvert the medium’s entertainment value.

3. Visual Entertainment’s Changing Faces

The original Star Trek, consequently, has little to do with mass-media entertainment, preferring to relegate visual media to the functions of information exchange and personal communication. This resistance disappears when the holodeck becomes an important component of Star Trek: The Next Generation’s Enterprise-D, resulting in an enduring reflection on the uses, limits, and possibilities of mass media that extends to later Star Trek series.

Star Trek: Deep Space Nine’s Ferengi entrepreneur Quark (Armin Shimerman), for instance, owns and operates several commercial holosuites that, like 20th-Century cinema and television, make their profits by offering a multitude of historical re-creations (including the Battle of Britain, the Alamo, and the Battle of Thermopylae), fictional dramas (including the inventive James Bond-style spy adventure that Dr. Julian Bashir [Alexander Siddig] has specially designed for him in “Our Man Bashir”), and sexual fantasias (including the oft-mentioned, but never-seen “Vulcan Love Slave,” as well as the nakedly provocative program that Quark is commissioned to design for a customer who wishes to enjoy sexual relations with a holographic version of the station’s first officer, Kira Nerys [Nana Visitor], in “Meridian”).

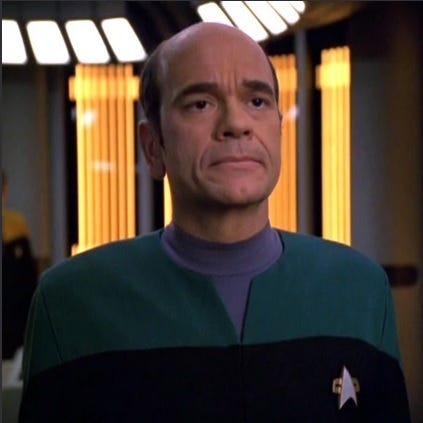

Star Trek: Voyager takes the implications of creating holodeck characters to their logical limit by making one of its principal crewmembers, Robert Picardo’s Emergency Medical Hologram (known only as “the Doctor”), a sentient being. Voyager also includes references to more standard, non-holographic mass media through the enthusiasm of the ship’s helmsman, Tom Paris (Robert Duncan McNeill), for 20th-Century American culture.

Paris even receives a surprise gift from his girlfriend B’Elanna Torres (Roxann Dawson) of a vintage, working 1956 television set in the episode “Memorial.” Star Trek: Enterprise, set two hundred years before the timeframe of The Next Generation, Deep Space Nine, and Voyager, features no holodecks, but its crew regularly attends Movie Night in the Star Trek franchise’s closest approximation of the 20th Century’s theatrical filmgoing experience.

We can see from these examples, which are only a fraction of the franchise’s explicit references to electronic mass media, that the producers of Star Trek’s later series not only rectify the original program’s disinterest in extrapolating new forms of visual entertainment but also redress the original’s steadfast refusal to mention older media forms. The Next Generation’s first-season finale, “The Neutral Zone,” even briefly mentions television’s demise.

The Enterprise-D intercepts an ancient Earth satellite that contains three 20th-Century people preserved in cryogenic stasis tubes. One man, after being revived, asks the Enterprise’s android officer, Lieutenant Commander Data (Brent Spiner), if he can watch television. Data’s reply is telling: “That particular form of entertainment did not last much beyond the year 2040.” Other entertainments presumably usurped television’s popularity, although the revelation in “Encounter at Farpoint” that nuclear war nearly destroyed humanity in the early 21st Century provides another explanation for why visual mass media did not survive into later eras.

Star Trek: First Contact, the movie franchise’s eighth film, depicts this “post-atomic horror” (Picard’s name for this historical era) as a time of almost total social breakdown in which the war’s survivors live in ragtag encampments that do not have the resources to produce onscreen visual entertainment (although rock-‘n-roll music and at least one functioning jukebox still exist). Television, in other words, dies not because humanity maintains no interest in it, but because other priorities are more pressing.

Cinema, however, lives into the 22nd Century, at least as an historical artifact. The crew of Star Trek: Enterprise routinely attends Movie Night, which Helmsman Travis Mayweather (Anthony Montgomery) first mentions in the episode “Cold Front” by commenting that, out of the fifty-thousand films in the ship’s database, a better selection than Night of the Killer Androids could have been made. In the series’s second episode, “Fight or Flight,” when Armory Officer Malcolm Reed (Dominic Keating) wants to bring large plasma rifles aboard a derelict alien spacecraft that the crew is preparing to board, Captain Archer wryly notes that such weaponry is unnecessary by saying, “You’ve watched too many science-fiction movies.”

The fullest discussion of Movie Night comes in the first-season episode “Dear Doctor,” when the NX-01 Enterprise’s Doctor Phlox (John Billingsley), a native of the planet Denobula, who is engaged in an epistolary exchange with his friend and colleague Dr. Jeremy Lucas, attends a screening of Sam Wood’s 1943 film adaptation of Ernest Hemingway’s novel For Whom the Bell Tolls.

As Ingrid Bergman and Gary Cooper talk onscreen in front of him, Phlox watches the reactions of the audience’s human crew members while discussing his observations with Elizabeth Cutler (Kelly Waymire), the woman sitting next to him. Cutler, who describes the ending of Wood’s film as “classic,” notices that Phlox is not paying close attention to the onscreen drama. “They don’t have movies where you come from, do they?” she asks him.

PHLOX. Well, we had something similar a few hundred years ago, but they lost their appeal when people discovered their real lives were more interesting.

CUTLER. Still, it’s nice to take a break from real life every now and then, don’t you think?

PHLOX. I suppose it is.

Phlox then notices the ship’s engineer, Commander Charles “Trip” Tucker (Connor Trinneer), crying as the film approaches its climax. When Tucker realizes that Phlox has seen these tears, Tucker explains away this outburst by saying, “Something in my eye.” Phlox, realizing that several other audience members, both male and female, are misty eyed, makes the following observation to Dr. Lucas in a voiceover excerpt from one of his (Phlox’s) letters: “It’s remarkable, Doctor, even fictional characters seem to elicit human compassion. My shipmates have calmly faced any number of dangers, and yet a simple movie can bring tears to their eyes.”

This comment can also be taken as a reflexive commentary on Star Trek’s existence as fictional entertainment, since many of the franchise’s characters—particularly those of the original program, The Next Generation, Deep Space Nine, and Voyager—have become so beloved that fans regard them as if they are real people.

More telling is how Cutler and Phlox both conceptualize cinema as escapist entertainment, or as a break from real-life problems that is finally not as intriguing as a person’s actual, lived existence. Tucker’s emotional reaction to For Whom the Bell Tolls’s denouement shows that responding to the film as a work of art is still possible in the 22nd Century, even if Phlox refers to it as “a simple movie” and if Denobulans no longer have need of such visual stimulation.

Enterprise, however, makes no reference to newly produced films. The crew does not assemble for the premiere of 22nd-Century movies, so we must assume that cinema is a dead art form that has somehow survived the test of time. Movies, however, do not prevent Enterprise’s characters from enjoying a variety of books, music, and sporting events (Archer, for instance, is a passionate water-polo aficionado).

Since Enterprise is a prequel to the original Star Trek, this portrayal of mass media as antiquated is necessary if the producers wish to maintain internal continuity with the rest of the franchise’s history, but the fact that so many older forms of visual entertainment than mass media survive into the 22nd, 23rd, and 24th centuries indicates an unwillingness on the part of Star Trek’s creators to portray film and television as sufficiently relevant, interesting, or significant to the space-going culture of their future world.

Visual entertainment, apart from theatrical stage productions, must take on a new form to satisfy the desires of Star Trek’s more cultivated characters. That form is the holodeck.

4. Holographic Worlds, Worldly Holograms

Enterprise depicts humanity’s first encounter with a holodeck. In the first-season episode “Unexpected,” Tucker boards a Xyrillian vessel to help repair its failing engines. During a lull in this work, a female Xyrillian engineer takes Tucker to a small room that precisely re-creates her home planet. Tucker is astounded by the authenticity of his holographic surroundings, causing Malcolm Reed, in a nod to the holographic adventures of other Star Trek series, to ruefully comment, “If we had one of those on board, I can only imagine what it would be used for.”

The real question is why Starfleet waits two centuries to install holodecks on its vessels, especially considering that “Unexpected” concludes with Archer and Tucker brokering a deal between the Xyrillians and the Klingons for the Xyrillians, who have trespassed into Klingon space and have accidentally disabled a Klingon vessel, to share their advanced holography to prevent the Klingons from destroying the Xyrillian ship. Why would Archer not negotiate to bring such a remarkable device aboard the NX-01 Enterprise so that his crew can enjoy its benefits?

One explanation is that Archer and his Starfleet superiors wish to invent the technology on their own, much as they have developed warp engines, transporters, and phase pistols for themselves rather than relying on extraterrestrial cultures. Considering that, in Enterprise’s era (the 22nd Century), the Vulcans actively resist providing humanity with technological assistance that they feel exceeds Earth’s capacity to use wisely, this notion has some merit.

A second explanation (and one of “Unexpected’s” many implications) is that Xyrillian holography becomes one basis for future Starfleet holodecks, which will require a few hundred years to perfect. A third possibility is that primitive holodecks were available during Archer’s and Kirk’s eras, but never depicted onscreen.

A simpler reason for this oversight, related to the original series’s budgetary limitations, is that Gene Roddenberry had not conceptualized every facet of 23rd-Century life when the original show went into production. The enormous number of details that Roddenberry and his writers had to keep in mind while creating an entirely new future world precluded them from carefully extrapolating the development of mass media.

As Solow and Justman’s Inside Star Trek and Stephen E. Whitfield’s The Making of Star Trek note, the severe time constraints imposed on the original Star Trek’s production staff by the staggering workload of preparing the series for weekly broadcast provide ample explanation for why such an obvious oversight (obvious to later viewers, that is) was made. The hurly-burly of getting Star Trek on the air forced Roddenberry’s team to fill in details of his fictional world as the series went forward.

The 18-year interregnum between the cancellation of the original Star Trek and the production of Star Trek: The Next Generation gave Roddenberry and his new team (which included veterans of the original series such as Robert Justman, D.C. Fontana, and David Gerrold) abundant time to redress some of the earlier program’s lapses. The holodeck is a major addition to Star Trek’s depiction of futuristic technology, as a 1987 memo reprinted in every edition of the Star Trek: The Next Generation Writers’ Technical Manual (a 40-page document that provides detailed technical information about the Enterprise-D) makes clear:

For many years it has been assumed by science fiction writers and engineers alike that long-duration space flights would require certain measures [be] taken to keep the travelers happy and psychologically fit for continued duty. [. . .] Flash ahead: Here we are in the 24th Century. Information storage and retrieval systems are sophisticated beyond our imaginations. Well, almost. We can imagine quite a lot. [. . .] This gives us the power to create terrain, structures, atmosphere—complete sensory environments. Things to walk over, sit on, swim under, or fly above. Combined with certain parts of a simulation being created by transporter technology, the holodeck provides a complete distraction. (29–30)

Although the holodeck is described as a method of maintaining psychological fitness and (in other parts of the Writers’ Technical Manual) as a valuable resource in crew training, the most notable aspect of this description is the holodeck’s escapist potential. Its primary uses are distraction, entertainment, and pleasure, the same qualities associated with 20th-Century mass-media forms like film and television.

The holodeck, indeed, extrapolates Marshall McLuhan’s conceptualization of a cool medium into the 24th Century by allowing total immersion in a simulated environment. This fact raises the Baudrillardian possibility that the holodeck’s “complete sensory environment” can so comprehensively distract the user’s senses that the simulation threatens to supplant reality.

The Next Generation’s writers exploit this possibility in four key episodes—“The Big Goodbye,” “Elementary, Dear Data,” “Hollow Pursuits,” and “Ship in a Bottle”—to suggest that powerful media technologies can create ontological worlds so seductive and potentially dangerous that their users must be constantly wary of losing track of reality. By creating a sentient holographic character in Daniel Davis’s Professor James Moriarty, The Next Generation also expands the potential of Star Trek’s simulated worlds to suggest that holographic characters can achieve personhood (a development that finds its fullest expression in Deep Space Nine’s Vic Fontaine [James Darren] and, especially, Voyager’s Doctor). Enterprise’s finale, “These Are the Voyages...,” brings the franchise’s use of holograms full circle to comment on mass media’s ability to create worlds, to interpret human experience reflexively, and to suggest that illusion is finally as important as reality.

These five episodes unveil Star Trek’s repeated invocation of simulated worlds to destabilize its characters’ (and its viewers’) ontological, epistemological, and historical certainties. Star Trek: Discovery employs such innovative and startling holographic technology that this program’s approach to the holodeck will form the basis of a future article.

5. Unreal Worlds, Real-World Dangers

The first Star Trek episode to focus fully on the holodeck is The Next Generation’s “The Big Goodbye,” a first-season entry that won the George Foster Peabody Award for broadcast excellence. It is also the first live-action “holodeck-in-jeopardy” story, in which the holodeck traps the crew in a dangerous, potentially lethal environment (a plot device that The Animated Series’s “The Practical Joker” inaugurates and that, some Star Trek fans complain, quickly became a cliché).

Picard, Data, Dr. Beverly Crusher (Gates McFadden), and a 20th-Century historian named Whalen (David Selburg) enter a holographic reproduction of the world of Dixon Hill, a fictional hardboiled detective who is a favorite literary diversion of Picard’s. When a particularly powerful alien energy beam probes the Enterprise-D, the holodeck malfunctions, trapping Picard and his officers inside, suspending the holodeck’s safety protocols, and placing the crew in peril.

Whalen is shot by a holographic character named Felix Leech (Harvey Jason), nearly dying as a result. At the episode’s conclusion, Leech and his employer, a criminal mastermind named Cyrus Redblock (Lawrence Tierney), achieve a measure of self-awareness when they see the holodeck’s doors open. Leaving the holodeck in hopes of plundering the Enterprise-D (“a whole new world,” as Redblock puts it), they quickly dissipate into nothingness.

Lieutenant McNary (Gary Armagnac), one of Hill’s police buddies who has interacted with Picard throughout the episode, then asks the captain, “When you’re gone, will this world still exist? Will my wife and kids still be waiting for me at home?” Picard can only respond by saying “I honestly don’t know” before exiting. The camera stays inside the holodeck with McNary, who does not disappear as other holodeck characters have. Instead, all lighting winks out a moment later, leaving the scene pitch black to suggest that holographic worlds do have their own, ephemeral integrity.

This episode is notable for how often and how well it blurs the line between fiction and reality, or entertainment and life. “The sense of reality was absolutely incredible,” Picard enthusiastically comments after his first, abbreviated visit to the holodeck’s recreation of 1941 San Francisco, while Crusher later tells him, “This is supposed to be a recreational activity.”

The fact that the holodeck can kill makes the broadest possible statement about the dangers of mixing reality and fantasy too intimately, while the self-consciousness that Leech, Redblock, and McNary achieve, apart from being a twist that Philip K. Dick would have appreciated, suggests that unreal characters can become fully formed persons if given the opportunity.

The second season’s “Elementary, Dear Data” fulfills this possibility. Data and Chief Engineer Geordi La Forge (LeVar Burton) impersonate Sherlock Holmes and Dr. John Watson on the holodeck. Geordi’s request for the computer to create a Holmes-like mystery with an opponent capable of defeating Data results in the holographic simulation of Professor James Moriarty (Daniel Davis) becoming fully conscious.

The fact that the Enterprise-D’s computer can create consciousness astonishes the crew and emboldens Moriarty to demand his rights as a living being. “I want my existence,” Moriarty says, citing Descartes’ dictum “Cogito ergo sum” as proof of his own sentience. “I am alive and I am aware of my own consciousness,” he tells Picard, who can only store Moriarty in the computer’s memory until a way to give holographic images substance—in other words, to make them real—can be discovered.

Even more intriguing is Moriarty’s description of the experience of becoming a person: “I have felt new realities at the edge of my consciousness readying to break through.” This line explicitly acknowledges the ontological and epistemological ambiguities that the holodeck engenders. Moriarty, who is only an insubstantial image, achieves self-awareness, if not personhood, because, as Geordi later realizes, the engineer misspeaks a single word.

The holodeck creates worlds and personalities to entertain and instruct the Enterprise-D’s crewmembers, but Moriarty’s case makes the situation much more complex. The realities that Moriarty senses on the edge of his consciousness unseat a strict division between reality and fiction, simultaneously alerting the critical viewer that Star Trek itself operates in much the same fashion. By creating a fully realized world and characters for its audience, The Next Generation raises the possibility that commercialized mass-media entertainment can powerfully influence its viewer’s sense of reality, with both positive and negative consequences.

Such adverse effects become evident in “Hollow Pursuits,” the third-season episode that introduces the recurring character of Reginald Barclay (Dwight Schultz). Barclay, a timid man who has trouble relating to his colleagues, retreats to the holodeck to become the hero of elaborate fantasies involving his crew mates.

The most notable is Barclay’s inclusion of characters from Alexandre Dumas’s The Three Musketeers within the setting of Thomas Gainsborough’s Blue Boy painting. In this unreal environment, Barclay is a master swordsman, a confident rake, and a thoroughly masculine character. The fact that he uses images of Picard, Data, and Geordi for the Musketeers, of Counselor Deanna Troi (Marina Sirtis) for the Grecian-inspired Goddess of Empathy, and of Will Riker for a diminutive, falsetto-voiced version of the first officer demonstrates the holodeck’s seductive pull.

Barclay spends so much time inside his fabricated realities that his professional life as one of Geordi’s engineering officers suffers. Geordi, in fact, tells Barclay that “you could write the book on holo-diction,” which is the franchise’s first explicit reference to the possibility that the holodeck, even when used for diversion and entertainment, can overwhelm a person’s ability to distinguish reality from fantasy. “You know, the people that I create in there are more real to me than anyone I meet out here,” Barclay says, confirming Geordi’s concern that Barclay cannot resist the temptation to live his life through holographic fantasies.

Barclay can also be read as a metaphor for Star Trek’s most passionate viewers, who have occasionally been accused (particularly by the popular press) of so thoroughly confusing Roddenberry’s fictional world with their own that they begin to live vicariously through Star Trek’s characters. This charge has been leveled against all mass media, especially television, since the mid-1950s, while social critics such as Jerry Mander, in his 1978 book Four Arguments for the Elimination of Television, decry television’s ability to submerge its viewers in an all-encompassing fictional world that not only threatens to overwhelm them but that also erodes their critical intelligence.

This argument is no surprise, since television, film, and even literature have historically been associated with indolence and inefficiency (serial novels, for instance, were called “penny dreadfuls” by Victorian critics who fretted about their corrupting cultural and educational influence). Watching television, in particular, has been considered a waste of time that could be better put to productive use almost since the medium’s inception, and “Hollow Pursuits” applies this seemingly reactionary stance to the holodeck. Barclay’s work suffers because of his holographic fictions, a state of affairs that is unacceptable to his superior officers.

Barclay overcomes this potentially debilitating condition to help solve a technological mystery that threatens the ship’s survival, realizing that he must leave the holodeck behind to function as a valuable member of the Enterprise-D’s onboard society. The episode concludes with Barclay relegating his fantasies to their proper realm, the imagination, which not only untangles the ontological and epistemological blurring that has threatened Barclay’s sanity, but also signals his acceptance that “real life” can be just as exciting as holographic adventures.

“Hollow Pursuits” is not, finally, as hostile to fiction or to mass media as these comments imply, but rather criticizes the tendency to get lost in imaginary worlds at the expense of adult responsibilities. The final scene, in which Barclay says farewell to the Enterprise-D’s command crew by accepting their words of praise about his character and abilities, is another holographic program that he plays out to achieve some closure. After discontinuing the program, Barclay deletes all but one of his holodeck fantasies from the computer’s memory.

The knowing smile on Barclay’s face (Schultz turns in a marvelous performance in this moment and throughout the episode) lets the viewer know that Barclay is on the path to integrating his vivid imagination with his quotidian life, making the boundary between fiction and reality more stable. “Hollow Pursuits” reveals that the holodeck can create a potentially dangerous mind warp, one in which the user gets lost within fabricated realities that, while they may not threaten a person’s immediate physical safety, can nevertheless upend an individual’s psychological equilibrium.

The sixth season’s “Ship in a Bottle” imbricates all the ontological and epistemological implications raised by “The Big Goodbye,” “Elementary, Dear Data,” and “Hollow Pursuits.” The power that simulated images can wield over human life becomes dangerously fascinating as Professor Moriarty returns to snare Picard and the Enterprise-D crew in a complex mise-en-abyme.

One of Data’s Sherlock Holmes programs malfunctions, causing Barclay, when he investigates, to activate Moriarty’s program. Moriarty claims to have been aware of the passage of time, even though he has been nothing more than a computer file for the past four years, by describing his experience as “brief, terrifying periods of consciousness… disembodied, without substance.”

Moriarty then amazes Picard, Data, and Barclay by walking off the holodeck, remaining whole and intact, rather than dissipating into nothingness. His explanation stresses the epistemological basis of all ontological existence: “Conscious beings have will. The mind endows them with powers that are not necessarily understood, even by you [Picard]. If my will is strong enough, perhaps I can exist outside this room. Perhaps I can walk into your world right now.”

The Nietzschean and Cartesian implications of this speech, in which Moriarty’s will to survive overcomes all existential obstacles, are notable. Picard tells Moriarty that he is, in essence, a new life form. When Moriarty requests that the love of his life, Countess Regina Bartholomew (Stephanie Beacham), be given consciousness so that she can join him in the “real world,” the episode becomes a story about the rights and freedoms of sentient individuals. Picard tells Moriarty that “the moral and ethical implications of creating another one like you are overwhelming,” as indeed they are, but even Picard’s concern for the Countess’s life does not mollify Moriarty, who gives her consciousness in the same way that he was given it (by telling the computer to create a character capable of defeating Data).

Moriarty’s will to survive becomes a will to power when Data realizes that the professor has not left the holodeck, but has instead created a simulation of the Enterprise-D within the holodeck to convince Picard, Data, and Barclay that they have returned to reality. This scheme allows Moriarty to gain access to the ship’s computer so that he can blackmail Riker into researching a method of bringing Moriarty and Bartholomew off the holodeck.

Picard, Data, and Barclay, however, program Moriarty’s fabricated holodeck to fool him into believing that he and the countess can survive in the real world. When Moriarty and Bartholomew leave the Enterprise-D in a shuttlecraft to explore the galaxy, they in fact do so only within the confines of an advanced memory module that, Barclay assures the crew, will give the professor and the countess enough adventures to last their entire lives.

The fact that Moriarty and Bartholomew have no physical substance, but believe that they do, constitutes The Next Generation’s richest intellectual statement about the holodeck’s ability to invent new realities that so fully warp a person’s sense of being that the mind can no longer distinguish between fact and fiction, simulation and reality, or imagination and lived experience.

Creating conscious, sentient beings capable of determining their own destiny means that the Enterprise-D’s computer can endow images with life, an advancement that inevitably questions the nature of what The Next Generation’s characters and audience perceive as authentic, consensual reality. Picard realizes the possibility that all life may be a simulation when, toward the conclusion of “Ship in a Bottle,” he comments, “Who knows? Our reality may be very much like theirs [Moriarty’s and Bartholomew’s], and all this might just be an elaborate simulation running inside a little device sitting on someone’s table.”

This Baudrillardian speculation indicates that the relationship between fiction and reality may become progressively more unstable until it threatens to reverse itself, with fiction finally commanding the lives of real people. Barclay, contemplating this possibility, calls out to the computer to end the program, half expecting that Picard’s comment indicates that the crew is still trapped in a holographic simulation.

He is understandably relieved when nothing happens (meaning that he is, in fact, back to reality). “Ship in a Bottle” does not linger over the unsettling possibility that all life is a fiction, but the mere suggestion makes this episode a worthwhile reflection about how interactive mass media can destabilize its viewers’ certainty about their ontological and epistemological integrity to the point that discriminating between imagination and reality seems impossible.

6. Keeping It Real?

Although Deep Space Nine’s holographic character Vic Fontaine and Voyager’s holographic Doctor provide their own fascinating examples of the holodeck’s ability to create sentient characters, Enterprise’s series finale demonstrates how advanced forms of mass media can not only be educational but also how mass-media entertainments change the nature of historical thinking.

“These Are the Voyages…” initially drew criticism from television critics and Star Trek fans for downplaying the importance of its core characters in order to accommodate guest appearances by Jonathan Frakes and Marina Sirtis as, respectively, Riker and Troi. The entire episode is a holographic simulation of Jonathan Archer’s final mission as captain of the NX-01 Enterprise, which Riker consults to help resolve the professional difficulty that he encounters during a seventh-season Next Generation episode titled “The Pegasus.”

In this episode, Riker’s first commanding officer, Admiral Eric Pressman (Terry O’Quinn), returns to search for the presumably destroyed starship Pegasus, which he, Riker, and a few other crew members abandoned before its destruction many years before. When Pressman reveals to Riker that the Pegasus was not destroyed, but rather that the illegal cloaking experiment that the crew was conducting in fact altered the ship’s molecular structure, Riker must decide whether to disobey Pressman’s orders to keep the truth (and his own complicity in violating Starfleet protocol and Federation treaty) from Picard.

“These Are the Voyages...” finds Troi counseling Riker to view Archer’s final mission to gain insight about how to balance loyalty to one’s colleagues with loyalty to historical truth. Enterprise’s finale, therefore, re-creates Archer’s final mission as a remarkably detailed historical simulation. Riker takes on several roles within Archer’s crew that give him a new perspective about the events of Star Trek’s early history that would, without the holodeck’s ability to bring them to life, exist only as words on a page or on a computer screen.

What scholar of the American Revolution, say, would refuse to enter interactive simulations of the first Continental Congress and the Battle of Concord if they were available? Riker’s simulation even finds him playing the role of the first Enterprise’s chef who, as Troi explains, was an early type of ship’s counselor that dispensed advice to the crew. Riker, posing as Chef, has personal conversations with all of Archer’s command staff.

This development forces the episode’s viewer to wonder exactly how Riker’s holographic program managed to include such intimate details. Did the program’s designer include personal logs by Archer’s officers in the simulation? Are such logs still available 200 years later, and even if they are, is including them in an interactive simulation for public consumption ethical? How can Riker and Troi be certain that the scenario visualized by the holodeck is historically accurate given the fact that, after two centuries, misunderstandings, exaggerations, and legends have undoubtedly grown up around Archer and his crew?

These questions raise important issues about the legitimacy of historical narratives. Riker’s simulation is most probably a mixture of known historical fact and imaginative extrapolation, since it seems unlikely that the simulation’s designer(s) could be certain of exactly what was said in 200-year-old private conversations. The program’s dialogues between Chef and Archer’s command crew become the episode’s fictional analogues of historical scholarship that “quotes” long-dead people even though transcripts of their conversations do not exist: the author must make best guesses based on available evidence as to what was said and done.

The holodeck, therefore, functions as a device capable of providing education, entertainment, and therapy in “These Are the Voyages...,” demonstrating the multiple uses, meanings, and implications that this advanced technology holds in Star Trek’s future world.

The episode’s critics are correct to assert that presenting the first Enterprise’s final adventure as a holodeck simulation diverts attention from Archer and his crew, but, in doing so, “These Are the Voyages...” suggests that history is a combination of fact, fiction, reality, and imagination. The world that Riker enters is not the actual world of Jonathan Archer’s final mission, but rather a startlingly real approximation that can easily be taken as the truth.

By re-creating an earlier era in amazing detail, the holodeck mediates historical reality with imaginative speculation to bring the Star Trek franchise full circle. Creating worlds within worlds is one of the holodeck’s primary functions, and as a metaphor for television’s ability to ensnare its viewer in fictions that seem authentically real, the holodeck alerts the thoughtful viewer to the extraordinary influence that mass media can hold over individuals (and even whole societies).

“These Are the Voyages...” has also, for some viewers, implied that Star Trek: Enterprise is nothing more than an historical holographic simulation, much as “The Last One,” the final episode of the 1980s hospital drama St. Elsewhere, implies that all its episodes have been imagined by an autistic boy.

This possibility, if true, would diminish the episode’s storytelling integrity. Even so, “These Are the Voyages...,” despite its dramatic lapses, is an intriguing instance of textual self-reflexivity on the part of Enterprise’s producers, meaning that this episode is an SF text aware of its own existence as commercial entertainment and of mass media’s authority to create fictional worlds that can dominate its audience’s epistemological and ontological perceptions.

Although the episode’s writers, Rick Berman and Brannon Braga, may not have intended this effect, “These Are the Voyages’s...” invocation of the holodeck fits squarely into Star Trek’s ongoing thematic concerns about the development, place, and power of mass media in future society. “These Are the Voyages...” may be a supremely dissatisfying conclusion to Star Trek: Enterprise, yet it remains consistent with the franchise’s portrayal of holographic worlds and mediated realities.

7. Goodbye (and Hello) to All That Media Jazz

Star Trek, therefore, proposes a fascinating, problematic, and complicated perspective about mass media’s survival, influence, and effectiveness in the detailed futuristic setting that the franchise’s many writers and producers have developed during its 55-year history. Although it has become fashionable, especially since Deep Space Nine ceased production in 1999, for journalists, television critics, and fans to reproach the franchise for imaginative sterility, Star Trek has regularly commented upon the possibilities and problems of America’s media-saturated society by using holographic simulations and sentient holographic characters to question the rigid division between reality and fiction that mass media destabilizes.

Since the year 2000, after all, entertainment technologies resembling Star Trek devices, including tablets and other “smart” devices that perform a variety of information-retrieval tasks (much like Star Trek’s tricorders and PADDs), have become realities, while the advent of streaming-video services now makes so much visual content available that viewers could spend all of their time watching television and/or computer screens.

Gene Roddenberry’s original Star Trek series may have failed to anticipate these developments, but the producers of the succeeding Trek television programs have redressed this oversight by theorizing that the logical extension of film, television, and other visual media is the creation of simulated environments that allow participants to interact within a virtual world identical to their lived experience.

The Next Generation, Deep Space Nine, Voyager, and Enterprise all demonstrate, with varying frequency and success, the epistemological and ontological difficulties that such precise simulations imply. When a person’s perception of authentic reality becomes unstable, that person can no longer say for certain what is real and what is fabricated.

This ambivalence, beyond its postmodern resonance, suggests not only that mass-media entertainments can be as influential as some of their harshest critics claim, but also that human beings, by engaging their critical faculties, can properly integrate mass media’s educational, aesthetic, and psychological benefits into their lives. Star Trek demonstrates that science fiction, by carefully extrapolating the evolution of media entertainment into future contexts, need not take its audience to extraterrestrial planets in order to create new worlds.

The holodeck becomes a metaphor that indicates how our fictions can become our friends, our enemies, and our equals. By envisioning a futuristic society in which imaginative objects, characters, and stories become tactile, Star Trek blurs the boundaries between reality and art to make skillful statements about how each realm depends upon the other for its existence, its relevance, and, most importantly, its human significance.

WORKS CONSULTED

Anderson, Hephzibah. “The Shocking Tale of the Penny Dreadful.” BBC, 2 May 2016, https://www.bbc.com/culture/article/20160502-the-shocking-tale-of-the-penny-dreadful.

“Big Goodbye, The.” Star Trek: The Next Generation. Written by Tracy Tormé. Directed by Joseph L. Scanlan. Paramount Television. 11 January 1988. 45 minutes.

“Charlie X.” Star Trek. Written by D.C. Fontana. Directed by Lawrence Dobkin. NBC. 15 September 1966. 50 minutes.

“Cold Front.” Enterprise. Written by Tim Finch & Stephen Beck. Directed Robert Duncan McNeill. UPN. 28 November 2001. 45 minutes.

“Conscience of the King, The.” Star Trek. Written by Barry Trivers. Directed by Gerd Oswald. NBC. 8 December 1966. 50 minutes.

“Dear Doctor.” Enterprise. Written by Andre Jacquemetton & Maria Jacquemetton. Directed by James A. Contner. UPN. 23 January 2002. 45 minutes.

Dick, Philip K. “The Defenders.” 1953. The Collected Stories of Philip K. Dick, Volume One: The Short Happy Life of the Brown Oxford. Citadel-Kensington, 1987.

—. Do Androids Dream of Electric Sheep? 1968. Del Rey-Ballantine, 1982.

—. “The Mold of Yancy.” 1955. The Collected Stories of Philip K. Dick, Volume Four: The Minority Report. 1987. Citadel-Kensington, 1991.

—. The Penultimate Truth. 1964. Bluejay, 1984.

—. The Simulacra. 1964. Vintage-Random, 2002.

“Elementary, Dear Data.” Star Trek: The Next Generation. Written by Brian Alan Lane. Directed by Rob Bowman. Paramount Television. 5 December 1988. 46 minutes.

“Encounter at Farpoint.” Star Trek: The Next Generation. Written by D.C. Fontana and Gene Roddenberry. Directed by Corey Allen. Paramount Television. 28 September 1987. 92 minutes.

“Fight or Flight.” Enterprise. Written by Rick Berman & Brannon Braga. Directed by Allen Kroeker. UPN. 3 October 2001. 45 minutes.

Hadas, Moses. “Climates of Criticism.” The Eighth Art: Twenty-Three Views of Television Today. Ed. R.L. Shayon. Holt, Rinehart and Winston, 1962.

“Hollow Pursuits.” Star Trek: The Next Generation. Written by Sally Caves. Directed by Cliff Bole. Paramount Television. 30 April 1990. 46 minutes.

“Last One, The.” St. Elsewhere. Written by Mark Tinker & Bruce Paltrow. Story by Tom Fontana & Channing Gibson. Directed by Mark Tinker. NBC. 25 May 1988. 54 minutes.

Mander, Jerry. Four Arguments for the Elimination of Television. Perennial, 1978.

McLuhan, Marshall. Understanding Media: The Extensions of Man. McGraw-Hill, 1964.

“Meridian.” Star Trek: Deep Space Nine. Written by Mark Gehred-O’Connell. Story by Hilary J. Bader and Evan Carlos Somers. Directed by Jonathan Frakes. Paramount Television. 20 November 1994. 46 minutes.

“Memorial.” Star Trek: Voyager. Written by Robin Burger. Directed by Allen Kroeker. UPN. 2 February 2000. 43 minutes.

Minow, Newton M., and Craig L. LaMay. Abandoned in the Wasteland: Children, Television, and the First Amendment. Hill and Wang, 1995.

“Neutral Zone, The.” Star Trek: The Next Generation. Written by Maurice Hurley. Story by Deborah McIntyre. Directed by Cliff Bole. Paramount Television. 16 May 1988. 46 minutes.

Newcomb, Horace. TV: The Most Popular Art. Anchor-Doubleday, 1974.

“Our Man Bashir.” Star Trek: Deep Space Nine. Written by Ronald D. Moore. Story By Robert Gillan. Directed by Winrich Kolbe. Paramount Television. 2 December 1995. 46 minutes.

“Pegasus, The.” Star Trek: The Next Generation. Written by Ronald D. Moore. Directed by LeVar Burton. Paramount Television. 10 January 1994. 45 minutes.

“Practical Joker, The.” Star Trek: The Animated Series. Written by Chuck Menville. Directed by Bill Reed & Hal Sutherland. NBC. 21 September 1974. 23 minutes.

“Ship in a Bottle.” Star Trek: The Next Generation. Written by René Echevarria. Directed by Alexander Singer. Paramount Television. 25 January 1993. 45 minutes.

Solow, Herbert F. and Robert H. Justman. Inside Star Trek: The Real Story. Pocket Books, 1996.

Star Trek: First Contact. Written by Brannon Braga & Ronald D. Moore. Story by Rick Berman, Brannon Braga, & Ronald D. Moore. Directed by Jonathan Frakes. Paramount Pictures, 1998. 111 minutes.

Star Trek: The Next Generation Writers’ Technical Manual or, “Yes, But Which Button Do I Push to Fire the Phasers?” Fourth Season Edition. Written by Rick Sternbach and Mike Okuda. Paramount Television, 1990.

“These Are the Voyages....” Star Trek: Enterprise. Written by Rick Berman & Brannon Braga. Directed by Allen Kroeker. UPN. 13 May 2005. 43 minutes.

“Unexpected.” Enterprise. Written by Rick Berman & Brannon Braga. Directed by Mike Vejar. UPN. 17 October 2001. 45 minutes.

“Way to Eden, The.” Star Trek. Written by Arthur Heinemann. Directed by David Alexander. NBC. 21 February 1969. 51 minutes.

“Where No Man Has Gone Before.” Star Trek. Written by Samuel A. Peeples. Directed by James Goldstone. NBC. 22 September 1966. 50 minutes.

Whitfield, Stephen E. The Making of Star Trek. Del Rey-Ballantine, 1968.