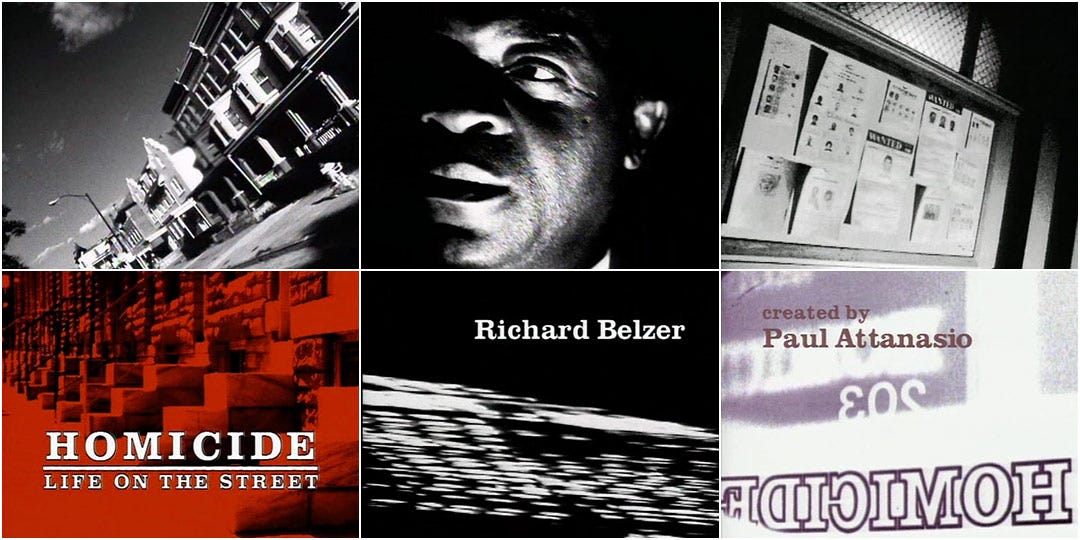

Homicide: Life on the Street

Created by Paul Attanasio

Based on Homicide: A Year on the Killing Streets by David Simon

Starring Daniel Baldwin, Ned Beatty, Richard Belzer, Andre Brauger, Reed Diamond, Giancarlo Esposito, Michelle Forbes, Peter Gerety, Isabella Hofmann, Želko Ivanek, Clark Johnson, Yaphet Kotto, Melissa Leo, Toni Lewis, Michael Michele, Max Perlich, Jon Polito, Kyle Secor, Jon Seda, and Callie Thorne

Guest Starring Ami Brabson, Erik Todd Dellums, Gerald F. Gough, Wendy Hughes, Clayton LeBouef, Harlee McBride, Ellen McElduff, Walt McPherson, Austin Pendleton, Kristin Rohde, Ralph Tabakin, Judy Thornton, Sean Whitesell, and Sharon Ziman

122 one-hour episodes & 1 two-hour telefilm

Original broadcast 31 January 1993 — 21 May 1999 (series) & 13 February 2000 (telefilm)

1. Off-Air Adventures

Perhaps the cruelest irony of television’s Streaming Era is that, despite the abundance of small-screen entertainment now available to us all at all hours of all days (and all nights), some fondly remembered programs elude discovery no matter how hard we search for them.

Two terrific series from the American 1990s have never been available on any streaming service despite their seminal status (well, seminal to me and plenty of other people): Paul Attanasio’s Homicide: Life on the Street (1993-1999) and Chris Carter’s Millennium (1996-1999).

Both shows received season-by-season DVD releases during the 2000s, then series-spanning DVD box sets during the 2010s, but, with time’s passage, these items’ availability has waxed and waned given the effort, energy, and expense required to secure music rights and other permissions from Homicide’s and Millennium’s broadcast lives.

The result?

The purchase prices of Homicide and Millennium DVDs have skyrocketed on Amazon, eBay, and other online auction sites, which is unsurprising and depressing for fans unwilling or unable to shell out the necessary cash.

That’s a polite way of saying that both programs’ most-ardent admirers have been out of luck for so long they’d come to accept that—short of illegal downloads and unlicensed streaming from various websites I won’t name here (but that you can locate with only a little online sleuthing)—they’d never see these sterling series again. Sure, Court TV picked up Homicide for daily broadcasts (a process known as “stripping”) after its original NBC run concluded in 1999, but these repeats petered out after only a few years, just as the now-defunct Chiller TV service rebroadcast Millennium for a year or two after Chiller’s 2007 launch.

Yet how many people—other than nutcases like myself—remember the brief afterlives of two of the best dramas ever to appear on American television?

Millennium fans, I’m sorry to report, remain hard-up vis-à-vis streaming, but Homicide aficionados can now rejoice. The entire series (plus Homicide: The Movie, the 2000 telefilm that saw all 20 principal Homicide cast members from across the program’s seven seasons—including performers who’d departed five and six years prior—unite to close one final case) is now available on Peacock, NBC’s aptly named streaming service.

2. On-Air Adaptations

Although Peacock first made Homicide available on 19 August 2024, I somehow missed all the hoopla surrounding this blessed event, including Eric Deggans’s short-but-thoughtful All Things Considered interview with Homicide’s showrunner, the redoubtable Tom Fontana, about why the program still matters. Having written a book about David Simon,1 author of 1991’s Homicide: A Year on the Killing Streets (the text that inspired Fontana’s series), that devotes an entire chapter to Homicide: Life on the Street (addressing not only its production but also its relationship to its source material), I really should’ve known that Homicide was returning to television one-quarter of a century after it departed our collective airwaves.

Indeed, I’d been revisiting, during 2024’s eventful summer, one of Homicide’s spiritual, if not actual, predecessors—Richard Levinson’s and William Link’s incomparable Columbo (1971-2003)—by savoring this older program’s episodes and, especially, Peter Falk’s remarkable portrayal of the Los Angeles Police Department’s (LAPD’s) Lieutenant Columbo (among the greatest performances ever given by any actor in any medium). So I nearly jumped for joy when I saw, one early September evening after activating Peacock to screen yet another Columbo telefilm, that Homicide was now available for streaming.

Columbo forgotten, I immediately began binge-watching Homicide, ripping through its first two seasons (of only 13 episodes, nine from Season 1 and four from Season 2) in just one day, discovering along the way that, while Peacock had remastered each episode’s audiovisual tracks (good), it hadn’t secured the rights to all the songs heard during the show’s network run (not so good). The audiovisual clarity of Peacock’s version of Homicide is impressive even if Peacock’s grandees decided to alter the series’ original 4:3 aspect ratio to fit the widescreen televisions that’ve become standard home appliances in the decades since Homicide was produced for those boxy TV sets we all once owned (and, strictly speaking for myself, loved).

This change has been admirably managed, with Peacock’s technical gurus somehow not sacrificing Homicide’s jump-cutty, innovative-in-its-day cinematography to the pan-and-scan priorities2 of the VHS Era, that 25-year period spanning the late 1970s to the early 2000s, when videotapes spawned an entirely new way of watching, first, films and, later, television series that’d previously been relegated to premium cable channels like Home Box Office (yes, some of us actually called it that rather than HBO) and Cinemax (or, as it was known to precociously prurient teenagers like myself, Skin-E-Max) unless you stayed up late, into the wee hours, to watch local-access TV stations run public-domain movies in six- and eight-hour blocks (the 1959 Vincent Price shocker The Tingler was a particular favorite, probably because it cost nothing—or next to nothing—for these stations to license) or were lucky enough to receive, on your basic-cable system, TBS (no one, in my memory, ever called it the Turner Broadcasting System—too many syllables), enabling you to enjoy endless reruns of the 1982 Marc Singer cult classic The Beastmaster, which for many years seemed to be the only movie that TBS owned, at least until Bob Clark’s 1983 holiday staple A Christmas Story came along and, a few years later, founder Ted Turner disastrously chose to “colorize” black-and-white classics like Michael Curtiz’s 1941 Casablanca and John Huston’s 1941 adaptation of Dashiell Hammett’s 1930 novel The Maltese Falcon.

And Peacock’s Homicide, to extend this discussion, sometimes looks even grainier than its broadcast version, while the missing music forces Peacock to incorporate replacement songs that can grate the nerves of faithful viewers who watched the show during its 1993-2000 NBC run and, years later, watched it all over again after purchasing the complete-series boxset (I’m a card-carrying member of both clubs).

For instance, the beautifully written, performed, and filmed Season 3 episode “The Last of the Watermen” (first broadcast on 9 December 1994) brilliantly integrated the Counting Crows’s 1993 song “Raining in Baltimore” into two montages—of Detective Kay Howard (Melissa Leo) driving to and away from her hometown of Tighlman Island, Maryland—only to have Peacock insert a song titled “Your Heart is the Lighthouse,” from an album titled Rescue Me that I’ve only located on SyncStories, a website that describes itself as “a one-stop music licensing and publishing company for TV, Film and Interactive Media,” but that doesn’t list the female singer’s name, only the songwriters (Eric Andrew Taylor & Lance Winnor Conrad), meaning that Peacock went with “library music”—i.e., songs compiled for the express purpose of replacing the commercial music whose rights the studios, the networks, and the streaming services can’t secure, can’t afford, or both—rather than ponying up the cash that the Counting Crows (or, more likely, Geffen Records and its corporate master, Universal Music Group) demanded.

Now, “Your Heart is the Lighthouse” works well enough in context, both underscoring and counterpointing Kay Howard’s forlorn trip home, but this track doesn’t achieve the matchless poetry of “Raining in Baltimore” undergirding melancholy images of Kay fleeing Baltimore for her childhood stomping grounds only to depart Tighlman Island soon after investigating a murder that implicates old friends, old boyfriends, and even family members.

3. In-the-Air Accolades

Homicide, to state the matter plainly, is one of four American television series—the others are Rick Berman’s & Michael Piller’s 1993-1999 Star Trek: Deep Space Nine, Steven Bochco’s & David Milch’s 1993-2005 NYPD Blue, and Chris Carter’s 1993-2018 The X-Files—that helped establish 1993 as a watershed year for small-screen television drama. This notable TV season created and imbibed the hopeful-yet-melancholy, forward-looking-yet-backward-gazing vibes so unique to the early 1990s that, with the Reagan Years ending and the Clinton Era looming, they became halcyon days for people who, hoping to surmount the Me!-Me!-Me! excesses of 1980s’ America, found their quest for new beginnings and their dreams of a better future relapsing into the neo-conservative bullshit and civic ennui that we’ve endured ever since.

That’s not the sunniest place to conclude 2025’s inaugural Vestibule post, but, then again, Homicide isn’t the sunniest television series to relish now that the new year has begun. As showrunner Tom Fontana’s joked many times since Homicide’s demise, whenever NBC programming executives asked him, “Where are the life-affirming moments that’ll keep viewers coming back for more?,” he always replied that Homicide, perhaps television’s ultimate downer title, ruled out happy endings no matter how much these network suits wished otherwise.

And what can one say in reply to this statement besides, “Right on, Tom”?

No, the real reasons to watch Homicide again—or, dear reader, for the first time (and to those people, you can’t imagine how jealous I am that you get to experience this fabulous work of art as freshly as I once did)—are: 1) to be impressed by how influential this program’s approach to cop dramas has become in the subsequent decades and, most importantly, 2) to marvel at how terrific are its writing, its production, and, especially, its acting.

Homicide, after all, is the program that launched Richard Belzer’s remarkable run as John Munch (not only one of the longest-running characters to appear on American primetime television—the third-longest, in fact, after fellow Law & Order: Special Victims Unit co-stars Mariska Hargitay’s Olivia Benson and Ice-T’s Odafin Tutuola—but also the character who’s appeared on more television series than anyone else in primetime history)3 and that brought three late-great film actors—Ned Beatty (1937-2021), Yaphet Kotto (1939-2021), and Jon Polito (1950-2016)—to series television in prominent roles that helped redefine their careers.

The aforementioned Melissa Leo won the 2010 Academy Award for Best Supporting Actress (for David O. Russell’s The Fighter) and the 2012 Emmy Award for Outstanding Guest Actress in a Comedy Series (for Louis C.K.’s Louie), although she should’ve gotten her first Emmy for playing Kay Howard so well in Homicide that, when this character exits the program in its fifth-season finale (“Strangers and Other Partners”), the show goes on, but loses the formidable spark that Leo gives it every time she talks.

And, of course, there’s the late-great Andre Braugher’s superlative work as Detective Frank Pembleton, among the greatest characters ever to grace an American television drama thanks to Braugher’s coruscating brilliance in this role and, it goes without saying (but I’ll say it anyway), to the writing staff’s genius in giving Braugher (1962-2023) the words necessary to bring Pembleton to such lucid and vivid life. Viewers who only know Braugher from his final, equally great TV role (as Captain Raymond Holt in Dan Goor’s & Michael Schur’s 2013-2021 workplace comedy Brooklyn Nine-Nine) might be shocked to see Braugher playing it straight as Pembleton, a Black New Yorker who prefers living in the “Brown town” of Baltimore, Maryland, and whose unsparing interrogations of homicide suspects (inside a room nicknamed “The Box”) are the inevitable highlights of any episode that features them.4

Braugher is so excellent as Pembleton that we must praise how good Kyle Secor is as Detective Tim Bayliss, Pembleton’s partner for most of Homicide’s first six seasons and the fresh-faced rookie who arrives in “Gone for Goode,” the series premiere, so eager to please that his earnestness makes Bayliss the immediate target of the squad room’s mockery. Secor’s ability to match Braugher’s intensity is nowhere better seen than in the program’s sixth episode, “Three Men and Adena,” set almost exclusively inside “The Box” as Pembleton and Bayliss interrogate, over a grueling twelve-hour session, a man named Risley Tucker, the chief suspect in the murder of 11-year-old Adena Watson who’s played to perfection by the late-great Moses Gunn (1929-1993) in his final screen performance.

Tom Fontana won the 1993 Emmy Award for Outstanding Individual Achievement in Writing a Drama Series for this installment’s script, which so confidently breaks cop-drama conventions that Bayliss and Pembleton fail to secure a confession from Tucker, who, in “Three Men and Adena’s” fabulous final act, begins interrogating the detectives’ insecurities before walking away from a crime that, like its real-life counterpart in David Simon’s book (the 1988 murder of 11-year-old LaTanya Kim Wallace), the squad never solves (violating the cop-show cliché of giving closure to every case even if the perpetrator isn’t punished).

So remarkable is “Three Men and Adena” that it moves critic John Leonard to declare, in Theodore Bogosian’s 1998 Public Broadcasting Service (PBS) documentary “Anatomy of a Homicide: Life on the Street” (a 71-minute, cradle-to-grave examination of how Season 6’s episode “The Subway” is produced), that “Adena”

was the most extraordinary thing that I have ever seen in a television hour. Just these three people and the overflowing black ashtray and the coffee cups that seem to be filled with amphetamines and spiders, the tension built up and the reverse torque of the two cops, and then, when Gunn himself went after them and found their weak points and completely reversed the psychology of the show, and they did not succeed, and I looked at that and I thought, “That’s better than Ariel Dorfman’s Death and the Maiden on Broadway, that’s better than a number of Don DeLillo novels about what happens to men in small rooms,” this was really wonderfully achieved. Big-city contemporary problems: wonderful stuff.5

Endorsements don’t get any better than this panegyric to an hour of television so powerful that I include Fontana’s teleplay in nearly every university course I teach as an example of beautiful writing (screenwriting, to be sure, but also writing, full stop).

I go could go on and on (and on) about how fantastic nearly every episode and nearly every actor in Homicide’s seven-season run is. Clark Johnson makes Detective Meldrick Lewis one of the lankiest, funniest, and coolest police officers in the history of American television and, to boot, began his thriving directorial career with Homicide’s Season 4 episode “Map of the Heart.” Indeed, Johnson became so good a director that he helmed the 2002 pilot episodes and the 2008 series finales of two later cop dramas that also redefined the genre (namely, Shawn Ryan’s The Shield and David Simon’s The Wire). And Toni Lewis, a late (fifth-season) arrival, shines as Detective Terri Stivers, making me regret that she’s appeared in only 11 film-and-television productions since Homicide went off the air.

Did you know that the great Giancarlo Esposito played FBI-agent-turned-Baltimore-homicide-detective Mike Giardello, son of Yaphet Kotto’s Al Giardello, in the show’s seventh-and-final season (plus Homicide: The Movie), showing attentive viewers just how good he was in the years before essaying the role of drug kingpin Gustavo “Gus” Fring (in Vince Gilligan’s 2008-2013 series Breaking Bad and in Gilligan’s & Peter Gould’s 2015-2022 prequel/sequel, Better Call Saul), to say nothing of the other television programs and movies (including four cinematic collaborations with Spike Lee) in which Esposito’s starred since Homicide ended?

I could (and might) write an entire essay about the local actors that give Homicide the look, sound, and feel of the hometown production that it was, filming as it did in the Fells Point neighborhood’s Recreation Pier, with Baltimore performers Sharon Ziman (executive producer Barry Levinson’s sister) and Judy Thornton (as, respectively, Homicide Squad secretaries Naomi and Judy) being only two of numerous area actors that appeared on the show during its seven-year shoot.

Yet that’s the future.

For now, let’s cheer Levinson’s and Fontana’s masterpiece—and, yes, it’s unquestionably a masterpiece—returning to television after a 25-year interregnum (while hoping—against hope, it seems—that Chris Carter’s Millennium will soon receive similar treatment).

That’s among the best new-year’s gifts I can imagine, so, as my first Peacock binge-watch of Homicide: Life on the Street comes to a close, I wish everyone a happy, healthy, and Homicide-infused 2025.

FILES

NOTES

In truth, this 2010 volume—featuring the ungainly title of “The Wire,” “Deadwood,” “Homicide,” and “NYPD Blue”: Violence Is Power (a name, I never fail to point out, forced upon me by the publisher’s marketing department despite my manuscript bearing the moniker American Savagery)—is a half-book about David Simon, with the other half devoted to David Milch (co-creator of 1993-2005’s NYPD Blue and creator of 2004-2006’s Deadwood).

This study, as far as I know, remains the only extant scholarly monograph about each man’s status as a significant social realist. It’s much more fun than it sounds, or, at least, I thought so while writing this book, with my research requiring the terrible sacrifice of re-watching all four series listed in the book’s title, along with Steven Bochco’s & Michael Kozoll’s 1981-1987 cop drama Hill Street Blues—the program on which Milch got his start as a television writer and producer—and Simon’s superlative 2000 HBO miniseries The Corner, based on his & Edward Burns’s 1997 book The Corner: A Year in the Life of an Inner-City Neighborhood).

I’ll leave it to you, dear reader, to decide how good (or bad) Violence Is Power’s evaluations of all six series (and their creators) may be.

“Pan and Scan” describes the process of adjusting widescreen images to fit their rectangular (16:9) aspect ratios into the square (4:3) TV screens on which, until the advent of widescreen sets in the late 1990s and early 2000s, everyone—and I mean everyone, except the wealthiest among us—watched television.

Fullscreen (or, for the technically minded, standard-definition) TV was the only choice from television’s introduction into the commercial marketplace (during the late 1940s and early 1950s) until 2001 or 2002, when both widescreen and flat-screen TV sets became more common and more affordable, with, if memory serves, Black Friday 2005 being the tipping point, when so many retailers discounted the prices of widescreen TVs that, at least in St. Louis, Missouri, dumpsters all over the city filled with standard-def TV sets unceremoniously jettisoned to make room for their widescreen cousins.

Pan-and-scan adjustments, in the years since they first infiltrated the home-video market in the early 1980s, had been so roundly decried by filmmakers as varied as Spike Lee, Sydney Pollack, Martin Scorsese, Agnès Varda, and Wim Wenders (for altering a movie’s intended presentation) that few people now mourn “Pan and Scan” passing into obscurity, with younger readers perhaps never having seen an example of this technique unless, like me, they’re crazy cinephiles who occasionally seek out pan-and-scan versions of their favorite films to compare to their widescreen releases.

Belzer played Munch on 11 different American television series.

As a regular character, Belzer appeared from 1993-2000 as Munch in 122 episodes of Homicide: Life on the Street, including its concluding telefilm, Homicide: The Movie, and from 1999-2016 in 326 episodes of Dick Wolf’s ongoing series Law & Order: Special Victims Unit.

As a guest character, Belzer appeared in one 1997 episode of Chris Carter’s 1993-2018 series The X-Files (as Munch in Season 5’s “Unusual Suspects”), in four episodes of Dick Wolf’s ongoing Law & Order (as Munch in Season 6’s “Charm City,” in Season 8’s “Baby, It’s You,” in Season 9’s “Sideshow,” and in Season 10’s “Entitled”), in one episode of Tom Fontana’s single-season 2000 series The Beat (as Munch in Season 1’s “They Say It’s Your Birthday”), in one 2005 episode of Dick Wolf’s 2005-2006 series Law & Order: Trial by Jury (as Munch in Season 1’s “Skeleton”), in two 2006 episodes of Mitchell Hurwitz’s 2003-2019 series Arrested Development (as Munch in Season 3’s “Exit Strategy” and as himself in Season 3’s “S.O.B.s”), in one 2008 episode of David Simon’s 2002-2008 series The Wire (as Munch in Season 5’s “Took”), in two episodes of Tina Fey’s 2006-2013 series 30 Rock (as Munch in Season 5’s “¡Que Sopresa!” and as himself in Season 7’s “Hogcock!/Last Lunch”), in one 2015 episode of Robert Carlock’s & Tina Fey’s 2015-2019 series Unbreakable Kimmy Schmidt (as Munch in Season 1’s “Kimmy Goes to the Doctor!”), and—as Munch—in a comedy sketch performed on the 7 October 2009 episode of Jimmy Kimmel Live!

Needless to say, Belzer’s record playing Munch on so many different television programs may never be broken (and long may it stand).

See, for instance, Pembleton extracting a confession from a man he believes to be guilty in Season 1’s “Gone for Goode,” from a man he believes to be innocent in Season 2’s “Black and Blue,” and from a man he knows to be guilty in Season 4’s “For God and Country” for three examples of how terrifically Andre Braugher plays Pembleton’s genius for police interrogation.

“Anatomy of a Homicide: Life on the Street,” written and directed by Theodore Bogosian, Public Broadcasting Service, 4 November 1998, 71 minutes.

Bogosian’s documentary, available for viewing on YouTube at the time of writing, is included in Shout Factory’s “Homicide: Life on the Street: The Complete Series” DVD boxset, which, at the time of writing, costs less than $100 to purchase on websites like Amazon.com and Walmart.com.