0060

Six decades after Dr. No first hit movie screens, James Bond’s cinematic survival is cause for celebration and consternation.

1. Nobody Does It Better?

I come to praise James Bond and to bury him.

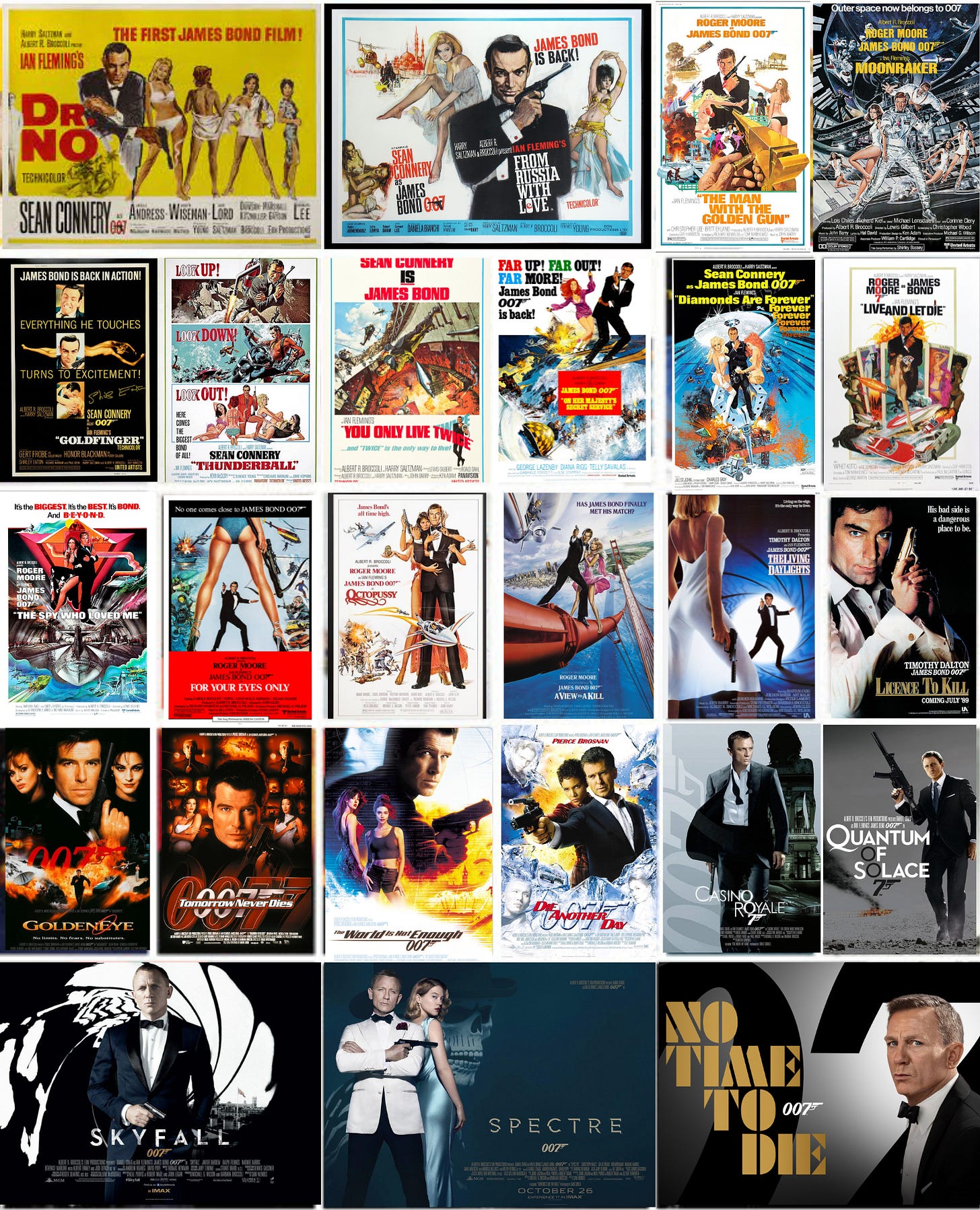

EON Productions’ inaugural cinematic adaptation of Ian Fleming’s espionage novels, the modestly budgeted Dr. No, premiered in the United Kingdom on 5 October 1962. People now claiming that they knew Bond would survive the shifting political, social, and cultural currents of the next 60 years to notch, on his filmic bedpost, 25 official movies, two unofficial films (1967’s Charles K. Feldman-produced spoof Casino Royale and 1983’s Thunderball remake Never Say Never Again), one animated spinoff television series (1991-1992’s James Bond Jr.), and a 26th official film in pre-production are—there’s no delicate way to say this, so I shall just say it—lying.

The Bond franchise has fascinated me my entire life, with the term franchise encompassing everything associated with the superspy: Fleming’s novels and short stories; the movies; the comic books; the video games; the board games; the continuation novels written by authors as diverse and distinguished as Kingsley Amis, John Gardner, Raymond Benson, William Boyd, and Anthony Horowitz (to name only five); plus the endless merchandise manufactured to promote EON’s film series (among the most prolific live-action movie cycles in human history, outnumbered only, as far as I know, by Britain’s Carry On comedy films, by Japan’s Godzilla pictures, by Marvel’s Cinematic Universe, and by China’s Wong Fei-hung / Huang Fei-hong martial-arts movies).

My first distinct memory of the onscreen Bond was watching, on television, Sir Roger Moore point a rifle at Marne Maitland’s groin in 1974’s The Man with the Golden Gun, a curiously appropriate introduction to the character, as well as one of the best scenes in what’s generally considered a bad Bond movie—indeed, among the worst—a production whose tone is so inconsistent and whose depiction of women so puerile that these flaws should, but don’t, stop me from being extravagantly entertained every time I see this decadent 1970s curio.

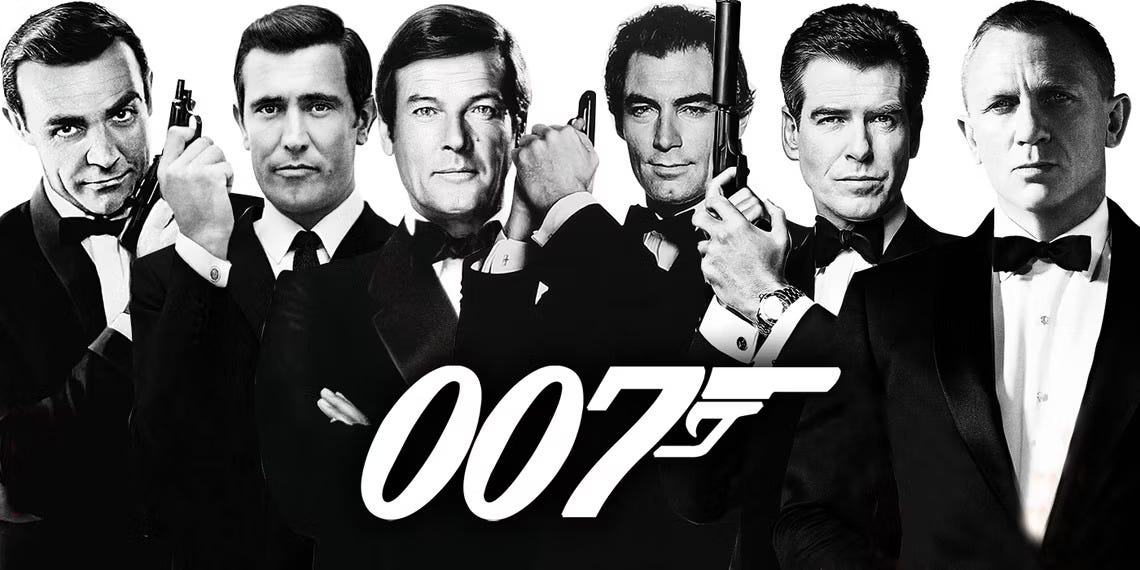

And I’ve seen The Man with the Golden Gun a dozen or more times, just as I’ve seen most Bond films at least as often. And in the case of 1989’s Licence to Kill, my favorite of them all—and if forced to choose the best entry in a franchise that has no single-best entry, the film that I judge the single-best Bond movie ever released (starring my favorite Bond actor, Timothy Dalton, although I’m a fan of all six men who’ve so far played 007 in the cinema)—probably 25 or 30 times, although I lost count long ago.

This fixation (perhaps obsession or sickness is the better term) occasionally shocks family members, friends, and colleagues, with my marvelous girlfriend, Patricia Thomas, once telling me (perhaps accusing me is the better description) of knowing more about James Bond than anyone who’s ever worked or watched the franchise.

She’s wrong about that final point, as proven by even a brief review of the many 007 fans with YouTube channels devoted to all things Bond (Calvin Dyson’s self-titled channel, Jeroen van den Brom’s DutchBondFan, and David Zaritsky’s The Bond Experience are all worth watching), to say nothing of the plentiful scholarship about Fleming’s long-lived protagonist. Did you know, for instance, that a publication titled The International Journal of James Bond Studies has released one issue every year since 2017? No? Well, all I’ll say is that you’d be well served to read every one of IJJBS’s articles no matter how busy you are.

And despite my familiarity with Bond’s history, I don’t regard myself as a “Bond scholar” despite, way back in 1993 and 1994, writing my undergraduate thesis (for Rhodes College’s Department of English) about Fleming’s Bond novels. This masterpiece bears what, at the time, I considered the terribly clever, punning title “The Marriage Bond,”1 a witticism that should’ve been my last, if you’ll forgive me paraphrasing Auric Goldfinger’s (Gert Frobe’s) comment to Sir Sean Connery’s 007 after strapping James Bond to a table made entirely of gold and pointing at 007’s privates an industrial laser (among the first, if not the first, ever seen in a theatrical film) midway through the movie named after this most iconic of all Bond villains.

In other words, since becoming a graduate student in 1998, I’ve never published so much as a research note about Bond in any academic journal and never given a single lecture about 007 to any scholarly conference. My point is that many people who’ve forgotten more about Bond than I’ll ever know wake up every morning and walk amongst us, even if my mind is—and I’m unsure if this metaphor is reason for pride or shame—a filing cabinet full of thoughts, dreams, trivia, and other ephemera about Fleming’s most famous creation, a character Ian once called, in a fit of despair, “that cardboard booby.”2

Then again, perhaps some comfort should flow from knowing that my Bondian fascination is a global phenomenon, at least if we trust box-office receipts, book-sales figures, and the fact that I’ve never visited any part of our world where 007 is unknown. To wit, during a 2008 trip to Bali, Indonesia, my travelling companions and I hired a touring van to take us all around the island, asking our driver, Sam, to stop in the smallest villages we could find. I was surprised to see that, no matter how remote the area, every market—no matter how small—had pallets of Coca Cola bottles stacked floor to ceiling.

These sights didn’t prepare me for the astonishment I experienced when, in one shop near the island’s southernmost point, I saw taped to its cash register a tattered 007 logo (you know the one, where Bond’s Walther PPK runs alongside the “7”) that’d been clipped out of a newspaper. The man working the register was, I came to learn, this place’s owner. He spoke no English and was, according to Sam (who doubled as our translator), 85 years old despite looking 25 years younger. When I pointed to the clipping and smiled, this elderly fellow mimed shooting us with two finger-guns before saying, in a fair-enough approximation of Connery’s Scottish brogue that everyone grinned from ear to ear, the words “Bond, James Bond” as if he’d played the role for much of his life.

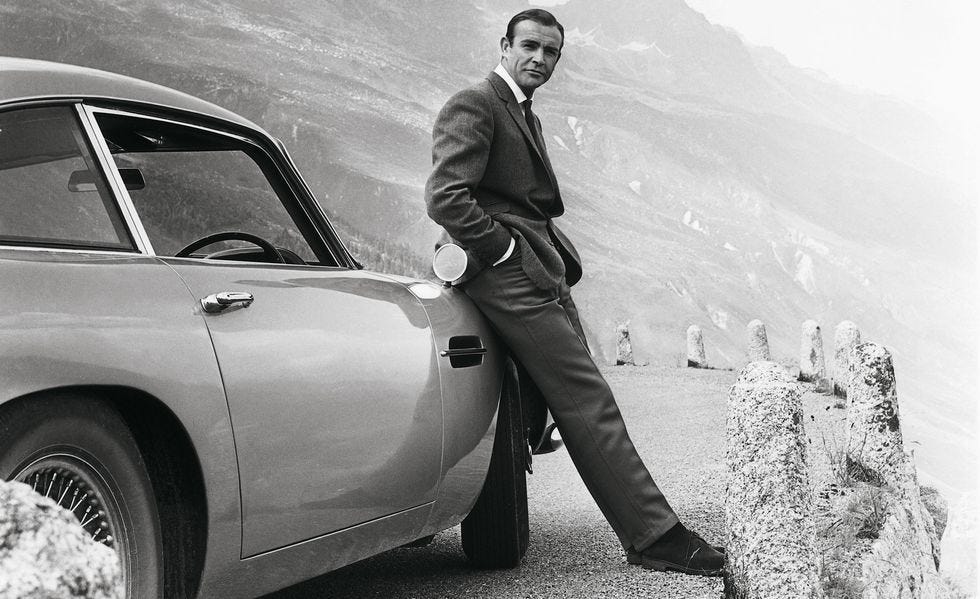

And no doubt he had, at least in his head, as so many of us (by us I mean men) have played Bond in our heads during the six decades since Connery originated the role on the silver screen.

Would you believe that James Bond is popular in one of the last Communist countries on Earth? I’d never thought about that notion, but on a 2017 trip to Luang Prabang, Laos—a city located at the confluence of the Mekong and Nam Khan Rivers in an area so gorgeous that it’s literally breathtaking—I visited a Buddhist temple just down the road from the small motel where I was lodging. I was properly impressed by this temple’s many statues and religious artifacts, yet also amused to see its younger monks looking at their smartphone screens when not praying or caring for the sprawling complex’s grounds.

One monk, who couldn’t have been more than 24 or 25 years old, had his phone’s speakers turned up high enough that I couldn’t help hearing Monty Norman’s and John Barry’s incomparable “James Bond Theme” issuing from them. And, being the Bond freak that I am, I instantly knew this monk was watching the gunbarrel sequence of a Bond movie, indeed the opening of 1987’s The Living Daylights, another favorite (and, happily, Timothy Dalton’s first film as 007).

Some other, similarly aged monks soon joined this fellow. No one said the words “Bond, James Bond” for the two or three minutes that I watched them watching Bond, but I’m sure at least one did before the movie and the morning ended.

Later, near lunch time, I visited a terrific open-air bar called Utopia staffed by some of the nicest people you’ll ever meet (and that, it must be said, nearly lives up to its name by sitting above a particularly lovely stretch of the Mekong River), where I mentioned this anecdote to Mele, the fellow serving me food and drinks. He said the Bond films had become sensations in Laos ever since its national government lifted the ban on them in the early or mid-2000s. Mele couldn’t remember exactly when this restriction was loosened, and my research hasn’t uncovered the exact date, either, or, truth be told, if the Bond movies were ever banned in Laos, but that’s a great story to tell as the franchise reaches its 60th anniversary, don’t you think?

2. Makes Me Feel Sad for the Rest?

Here’s another burning question. With praise of this type—meaning the legendary kind that may not be true, but that’s eminently truthful by underscoring how 007’s popularity is as high as it’s ever been—why did I begin this essay by saying that I come to bury James Bond?

Am I, you may wonder, one of those insufferable scolds who chastises people for enjoying whatever it is they enjoy, including the adventures of a British secret agent (or, more precisely, a not-so-secret agent whose name is known to hoteliers and bartenders the world over), an antihero who represents not merely the British establishment—staid, restrained, even repressed at times—but also the Western alliance’s most retrograde political traditions and, inevitably, its most regressive social, economic, and sexual viewpoints?

The answer is “No!” even if I understand, intellectually at least, all the reasons that Bond should be passé. He’s a politically conservative figure, at least in Fleming’s hands and in the early movies, with Connery’s Bond declaring in 1964’s Goldfinger that “drinking Dom Perignon ’53 above the temperature of 38 degrees Fahrenheit” is “as bad as listening to the Beatles without earmuffs.” No other statement could have situated 007 more firmly on the side of order and tradition in the burgeoning culture wars of the day, but, even so, you’ll be happy to learn that any animosity felt by the Fab Four was officially extinguished when Paul McCartney agreed to write the title song to 1973’s Live and Let Die, Roger Moore’s debut as James Bond (and the first of Moore’s seven consecutive movies, a franchise record that’ll probably go unequalled for all coming time).

Bond, especially in those films of the 1960s and early 1970s, becomes the walking embodiment of what some observers call toxic masculinity, for, in these movies, 007 ignores the notion of consent whenever it suits him. Connery’s 007—no matter how handsome, sexy, and seductive he may be—is prone to grabbing women and kissing them without warning or permission, sometimes gluing his lips to theirs until they melt into his arms and start enjoying the experience—a risible reaction that happens more than once in his six EON movies.

“Any woman he wants, he gets,” Tom Jones sings in Thunderball’s title song, and it’s easy to see why: When you refuse to take “no” for an answer in the expectation that she’ll grin and bear your advances, it becomes difficult not to think of yourself as the world’s greatest lover.

That’s when Connery’s not swatting women’s behinds, blackmailing them into coitus, or slapping them across the face. His 007 roughs up women (or allows them to get roughed up) in his six EON movies, to the point that, when George Lazenby’s one-off Bond grabs the wrist of Diana Rigg’s Teresa di Vincenzo in 1969’s On Her Majesty’s Secret Service, twists it to the point that she says “you’re hurting me,” strikes her full in the face, and then comments “I can be a lot more persuasive,” well, what can we say about this interaction?

Anyone wondering if Lazenby’s 007 is the same character as Connery’s (rather than a new agent going by the code name “James Bond”) has those doubts laid to rest once and for all, while the fact that Tracy wears a bathrobe hanging open to reveal her brassiere and cleavage while brandishing Bond’s own Walther PPK against him is just about as far from a progressive, late-60s depiction of women as you can get.

Now it’s true that Tracy takes her fate into her own hands and turns the tables on Bond here, with complicated sexual undercurrents bubbling just beneath the surface, while Rigg’s terrific performance makes Tracy far more than a one-night dalliance for Bond. Yet what would you say if I revealed that Tracy comes to Bond’s hotel room to repay the debt she owes him for covering her gambling losses at the baccarat tables only a few minutes before? How might you react if I mentioned that these events occur after Bond saves the suicidal Tracy from drowning herself in the ocean during the film’s opening sequence?

And what would your opinion be if I said that, after all this strange stuff happens in the movie’s first 30 minutes, Bond and Tracy begin a love affair that culminates in them marrying each other, only to see Tracy gunned down by Bond’s arch-nemeses Irma Bunt (Ilse Steppat) and Ernst Stavro Blofeld (Telly Savalas) while she and Bond drive to their honeymoon?

Does this perspective make you feel better or worse about their relationship, now considered the deepest and most emotionally resonant connection Bond has with any woman in the entire movie series (at least until Daniel Craig’s Bond commits himself to Léa Seydoux’s Madeleine Swann in 2021’s No Time to Die)? Blofeld’s lethal violence against Tracy at OHMSS’s conclusion may seem to excuse Bond’s casual violence against her earlier in the film, but these actions exist on a continuum within the movie itself, making claims that we shouldn’t judge the sexual mores of the 1960s by the standards of the 2020s—what I call the “it was a different era” defense—ring hollow despite the fact that keeping historical context in mind is always a good idea, if not always a good excuse.

Even Roger Moore, long considered the softest actor to play 007, gets into this act in The Man with the Golden Gun by slapping, pushing down onto a hotel bed, and threatening to break the arm of Maud Adams’s Andrea Anders, a woman trapped by villain Francisco Scaramanga (Christopher Lee) into a sexually exploitative “relationship” that sees this man, the world’s deadliest assassin, force her to live on a remote Southeast Asian island, cater to his every whim, and endure Scaramanga’s habit of stroking his golden gun along her body when he’s feeling amorous.

That’s not simply a sick metaphor, either, since Scaramanga shoots down his victims with a weapon made wholly out of gold, a firearm that, in one particularly disturbing scene, he wields as a massage toy—rubbing it along Andrea’s right arm, upper chest, and lower lip while she sits, clearly naked, under the covers of the bed she shares with Scaramanga aboard his plush junk (i.e., Chinese sailing ship). So how objectionable is it that Andrea sets the entire film’s plot in motion by sending Bond a golden bullet with the number “007” engraved into it hoping that this clue will induce James to locate and kill Scaramanga, thereby freeing her from the latter’s sexual slavery? She even gives herself to Bond in another scene, saying, “You can have me, too, if you like. I’m not unattractive. I’ve dreamed about you setting me free” to drive home the point that Bond should consider Andrea his reward for a job well done.

And this encounter occurs while Bond’s MI6 assistant-cum-secretary Mary Goodnight (Britt Ekland) rests under the covers of the bed on which Bond and Andrea sit. Mary comes to Bond’s hotel room to enjoy a night of passion after spurning his advances not five minutes before, causing Bond to hustle his hapless paramour into the room’s closet when Andrea goes to the bathroom to freshen up, bringing whole new meanings to the term bed hopping.

As outrageous as these examples are, as immature as their regard for women may be (puerile, the term I used earlier, seems even more appropriate now than it did then), and as many more cases as I can cite from memory, the fact remains that I can cite them from memory. Yes, friends, I’ve watched and re-watched the Bond movies, just as I’ve read and re-read the Bond novels, so many times that I’m not merely a Bond aficionado, not simply a Bond enthusiast, but indeed a card-carrying Bond fanatic (the root wood from which the term fan derives) who adores the franchise so deeply that the doubts I document above, while sincere in their expression, may be little more than façades permitting me to indulge my love of all things 007 whenever the fancy strikes me, and, certainly, whenever a new film appears in cineplexes.

3. We Know His Name

So we—or, at least, I—must face certain uncomfortable truths, starting with the fact that Bond endures after 60 years on the screen (and 69 years on the page) thanks to—not in spite of—his sexism. Daniel Craig, while promoting SPECTRE (his fourth film as 007) in the autumn of 2015, went further by declaring, in a 25 September 2015 interview with The Red Bulletin’s Rüdiger Sturm, “let’s not forget that he’s actually a misogynist. A lot of women are drawn to him chiefly because he embodies a certain kind of danger and never sticks around for too long,”3 an appraisal that may be harsh, but only slightly so.

No matter how accurate this judgment is, it didn’t prevent Craig from earning as much as $100 million (or more) from playing James Bond over five movies and 15 years. Craig’s tenure is the longest continuous time span that anyone’s remained 007 on movie screens, although Roger Moore, as mentioned earlier, starred in seven Bond films over a 12-year span and Sean Connery, if we count his appearance in 1983’s unofficial Never Say Never Again, played Bond in seven movies over a 21-year span with, it’s important to note, the four-year gap between his fifth and sixth outings (1967’s You Only Live Twice and 1971’s Diamonds Are Forever) preceding the 12-year gap between his sixth and seventh (Diamonds and Never Say Never).

Given these givens, Craig’s criticism of the role that’s made him a household name and, not coincidentally, one of contemporary Hollywood’s top-earning actors may strike readers as either refreshingly honest or cynically hypocritical depending upon how seriously one takes Craig’s charge of misogyny. And, truth be told, I’m no better. Why, after all, do I continue following the escapades of such an unsavory character unless I, too, am a cynic, a hypocrite, and, at base, a dissembler?

The usual defenses may at first suffice because, yes, Bond is not merely a tradition but now a genre unto himself, as well as a prototypical male-fantasy character whose antics are fun to read and exciting to watch. The Bond books and films, despite their classification as spy thrillers, are just as accurately categorized as larks, as capers, and as pranks pulled on willing audiences smart enough to understand that James Bond isn’t a real person who exists in the world (even if, due to 007’s ubiquity, it sometimes seems that he does).

Since Bond isn’t an authentic spy plying his secret trade in the way that actual spies ply theirs, perhaps we shouldn’t worry about his popularity being any kind of statement against anyone’s personal integrity. Ian Fleming and the producers who’ve kept the filmic 007 alive for 60 years4 knew (and know) that Bond is, first and foremost, a magnificent entertainment meant to be enjoyed by people looking for pleasant diversions, bawdy laughs, and, most especially, a good time at the movies (and, for we fuddy-duddies, a good time in the reading chair, too).

And pleasure, that most elusive and ephemeral of qualities, is what Bond gives audiences even when their political, social, and cultural leanings lead them (by them I mean myself) to disagree with Bond’s actions, his attitudes, and his way of moving through the fictional world that Fleming and company have taken pains to create since the 1950s and 1960s. This longevity is an extraordinary accomplishment, or, indeed, a remarkable, ongoing, and developing chain of accomplishments. James Bond, it seems, will march on yet never age, even if every new movie and each new continuation novel reflects distinct cultural markers about the age that produces it.

What’s the upshot, you may ask? Only that, to quote those reassuring words seen at the end of every 007 film, “James Bond Will Return,” apparently forever—or, at least, for several more lifetimes.

Spectacle, pleasure, entertainment—all those desires that James Bond’s literary and cinematic adventures fulfill well enough that the franchise endures more than half a century after first appearing in our cultural firmament—are too frequently dismissed as easy, escapist, silly, and simplistic. The notion of desire, moreover, makes some people so uncomfortable that they feel the need to justify the pleasures they seek from literature, from cinema, and from art of all kinds despite no justification being necessary. And, yes friends, Bond is art whether or not the cultural puritans among us accept that idea as legitimate, so why put ourselves into a defensive crouch when we needn’t adopt one at all?

Yet here I am, defending the Bond franchise as if it’s a guilty pleasure when, rather than hanging my head in shame or flagellating myself in recompense for the imagined sins of enjoying and thinking about a cultural juggernaut that’s produced some damned fine work during its long life—novels and movies that are worth our time to read, to watch, to consider, and, best of all, to argue about into the wee hours—I should instead proudly declare my membership in a club boasting millions of members, all of them good people who enjoy the highs and the lows of a character that lives and breathes in our dreams as much as our—no, no, let’s stop right there!

It’s enough to say, without embarrassment or dishonor, that, yes indeed, we fanatics enjoy Bond. Given all the problems, tensions, and tragedies besetting our world as 2022 gives way to 2023, it’s lovely to realize that, somehow, we still possess the capacity for enjoyment at all.

And James Bond, no matter his other flaws and faults, helps us hone this aptitude to a sharp-enough point that, in the end, loving 007 is just fine, indeed more than fine because our response to this edifice of popular culture needn’t be brainless, ill-considered, or peremptory, but at its best helps us appreciate the capacious, sometimes subterranean, and always beguiling pleasures that fiction makes available to us—pleasures that unquestionably enhance and enrich our lives.

That, dear reader, is a highfalutin way of saying that I wasn’t born a James Bond fan, but that I shall most certainly die one. If that’s reason for consternation now and again, it’s reason for contemplation and celebration, too.

So, as Ian Fleming’s secret agent begins his seventh decade of cinematic life, I say, with profound affection and abundant good cheer, “Happy birthday, Mr. Bond.”

Here’s to the next 60 years.

NOTES

The full title of my undergraduate thesis project was—or is, since it still exists—“The Marriage Bond: Patriarchy, Narcissism, and Emotional Transfiguration.” I may one day summon the courage to publish this piece of my early literary criticism in The Vestibule to give my readers the opportunity to tell how much (or how little!) I’ve matured as a writer, if nothing else.

Andrew Lycett, Ian Fleming, Weidenfeld and Nicolson, 1995, pg. 427.

Daniel Craig, interviewed by Rüdiger Sturm, “Daniel Craig on Being James Bond,” The Red Bulletin, 25 November 2015, https://www.redbull.com/int-en/theredbulletin/daniel-craig-on-what-he-really-thinks-of-bond.

The EON producers who’ve made the James Bond films since 1962 are, in order, Albert R. “Cubby” Broccoli & Harry Saltzman (from 1962-1974), then just Broccoli (from 1974-1995), and then Barbara Broccoli & Michael G. Wilson—Cubby’s daughter and stepson—from 1995 until the present day.

Irish filmmaker Kevin McClory produced 1965’s Thunderball after pursuing a 1963 judgment of plagiarism against Ian Fleming in London’s High Court after Fleming lifted the novel Thunderball’s fundamental plot, basic themes, and essential characters from an unproduced screenplay co-authored by Fleming, McClory, and screenwriter Jack Whittingham without giving McClory or Whittingham proper credit.

Fleming settled the case after nine days of trial in the High Court, with one provision of this agreement requiring all subsequent editions of Fleming’s ninth Bond novel, first published in 1961, to bear the following credit line on their copyright pages: “This story is based on a screen treatment by K. McClory, J. Whittingham, and the author.”

The deal McClory made with Broccoli and Saltzman to produce Thunderball’s film adaptation gave McClory the right to remake this movie beginning ten years after its 1965 theatrical release. Like clockwork, McClory began preparing a rival Bond movie in 1975, going so far as to hire Sean Connery and spy novelist Len Deighton to co-write a screenplay whose drafts were variously titled James Bond of the Secret Service and Warhead.

This project, directed by Irvin Kershner and starring Connery in what would be the actor’s final movie performance as James Bond, eventually premiered as Never Say Never Again on 7 October 1983 in Britain, four months after EON’s 13th official Bond movie, Octopussy (starring Roger Moore in his sixth outing as 007), opened on 6 June 1983.

Robert Sellers’s 2007 Tomahawk Press book The Battle for Bond is the best study yet published about McClory’s complicated involvement in James Bond’s cinematic life, while Stevan Riley’s 2012 documentary Everything Or Nothing: The Untold Story of 007 covers this intricate history in detail, although, as a movie officially authorized by EON to celebrate the film franchise’s 50th anniversary, this production favors the Broccoli family’s side of the story despite including interviews with people close to McClory who don’t shy away from criticizing Ian Fleming’s, Cubby Broccoli’s, and Harry Saltzman’s high-handed—and occasionally cutthroat—behavior.

The Battle for Bond, in perhaps its best contribution to understanding how James Bond became a moviemaking behemoth, provides a blow-by-blow (and sometimes hour-by-hour) account of McClory’s fascinating half-life as a rival Bond film producer.