No Time to Die

Written by Neal Purvis & Robert Wade and Cary Joji Fukunaga and Phoebe Waller-Bridge

Story by Neal Purvis & Robert Wade and Cary Joji Fukunaga

Based on characters created by Ian Fleming

Directed by Cary Joji Fukunaga

Starring Daniel Craig, Léa Seydoux, Rami Malek, Jeffrey Wright, Lashana Lynch, Ralph Fiennes, Naomie Harris, Ben Whisaw, Ana de Armas, and Christoph Waltz

163 minutes

Released 30 September 2021 (in Asia & Europe) and 8 October 2021 (in Canada & the United States).

1. There He Goes Again!

My friends, I present you No Time to Die, the $250-million, 25th entry in the world’s longest-running spy-film series, which began all the way back in 1962 with a small, $1-million production titled Dr. No.

It’s an astonishing achievement.

Please read the previous sentence any way you wish. Do I say so about the Bond film franchise in toto? About No Time to Die only? About Daniel Craig’s fifth (and final) performance as Bond, James Bond? About all three together and separate?

Think what you will, dear reader, but please watch this movie and make your own judgments.

I could be wrong.

I may well be wrong.

Yet I don’t think I’m wrong.

No Time to Die has given me so much to ponder that, before seeing it, you may profit from considering these questions. When, for instance, was the last time a James Bond film moved you to tears? Meaning proper, dramatically earned tears, not the sort so many 007 fans shed while watching the morass of Pierce Brosnan’s final turn as the suave secret agent in 2002’s Die Another Day?

When was the last time a James Bond picture so engaged your mind, your emotions, and your spirit that even its lesser parts seem easily forgiven trifles, perhaps best ignored? When did a James Bond entry last earn the title masterpiece, or come so close that you uttered this word under your breath even as other viewers seemed less enamored of the movie than you? How recently has the performer playing James Bond been so terrific in the role that you thought he deserves every acting-award nomination possible despite the fact he won’t receive them?

For me, this last query is easy to answer: Daniel Craig in 2006’s Casino Royale (and, very nearly, in 2012’s Skyfall), Timothy Dalton in 1989’s Licence to Kill (and, very nearly, in 1987’s The Living Daylights), and Sean Connery in 1963’s From Russia with Love (and, very nearly, in 1964’s Goldfinger).

Perhaps my enthusiasm for No Time to Die lies partially in the fact that its arrival marks the first time I ventured to the multiplex since February 2020, just before pandemic lockdowns began. Another reason risks making me seem even more narcissistic, in that my predictions about the future so rarely come true that, when they do, I can’t help enjoying how good it feels to get things right. Yes, friends, such has occurred with this newest Bond movie. To avoid becoming insufferable on this point, I offer this short anecdote by way of context.

EON Productions announced the title of its 25th James Bond film as No Time to Die on 20 August 2019, two days before I began teaching a university course devoted to espionage-and-thriller fiction. My students wouldn’t begin reading Ian Fleming’s first, excellent James Bond novel, 1953’s Casino Royale, for one month (i.e., late September 2019), but they knew that we would, as we must, reckon with Bond: the novels, the films, the franchise, and the cultural phenomenon that have made the phrase “Bond, James Bond” and the code-number 007 household names.

Some students mistakenly assumed that Bond was the beginning and the end of spy fiction, meaning that they anticipated focusing only on Fleming’s Bond novels and EON’s Bond movies, having a grand old time (more akin to fun book-club sessions than dreary college-level classes) in the bargain.

Well, happily, we did enjoy a grand old time. My students, surprised by the historical scope and literary depth of espionage fiction, read Eric Ambler, James Fenimore Cooper, James Grady, Graham Greene, John Le Carré, Helen MacInnes, Viet Thanh Nguyen, Stella Rimington, and (in a nonfictional departure) even the Mueller Report with growing passion, becoming aware of how espionage-and-thriller tales qualify as vibrant, rich, and living categories of cultural production.

New entries—books, movies, television series, anime, graphic novels, video games, even board games—chum our cultural waters all the time, so spending four-and-a-half months reading, watching, and thinking deeply about spy stories helped us to recognize just how significant they can be.

Yet Fleming loomed large in my students’ collective consciousness, especially since a new Bond movie was shooting while our course was underway. This fact led students to bring late-breaking production updates to class, causing us to spend five minutes at the beginning of each session in what we came to call “No Time to Die time.” We all agreed to see the film together upon its April 2020 release date, then retire to a local pub to discuss it. What a fun, after-the-fact field trip that will be, we thought, with no inkling that, only a few months later, a pandemic would disrupt the life of every single person on Earth.

2. Here We Go Again?

Among COVID-19’s many casualties was No Time to Die’s release date, which had already been pushed from November 2019 to April 2020 thanks to production delays (Danny Boyle and John Hodge—the movie’s original director and screenwriter—left the project due to “creative differences,” Daniel Craig suffered an ankle injury that required surgery, and on and on). Bond 25’s theatrical opening was subsequently delayed three more times (to November 2020, then to April 2021, then again to October 2021), causing some fans wonder if the film was cursed and other fans to dub the movie No Time to Watch (or, my favorite, No Time to See).

This interregnum, of course, is one small drop in the vast ocean of the pandemic’s tragedy. As gloomy as the past twenty-or-so months have been, I’m pleased to report that one of my Bond predictions proved accurate. You see, part of my course’s No Time to Die time was spent debating the title’s meaning: What does it tell us about the movie’s plot, especially after Daniel Craig’s announcement that this film was his final outing as 007? Is the title symbolic? Is it a clever indication of what to expect? Is it just a throwaway phrase?

I ventured two guesses.

First, No Time to Die may mean precisely what it says: that the movie will plunge James Bond once again into world-shaking events that leave him no time to die. He must complete his mission while ignoring its lethal effects, as he always does, but, with Craig finishing his tenure as 007, the villain’s plot would be more nefarious—meaning more psychopathic—than usual.

And two, the title carries an implied comma: No, Time to Die. If read this way, with a slight pause between the first and second word, might Bond 25 do what no other movie in the franchise has? Might No Time to Die kill off Craig’s iteration of Bond or, at least, leave him so broken or injured that he can no longer play the spy game?

Since the franchise’s writers and producers have attempted, with sporadic success, to give Craig’s secret agent a story arc that takes him from raw recruit to seasoned veteran, would they extend this journey to its inevitable, final phase: dead man walking? After all, what better way to clear the decks for Craig’s successor in the role than providing the most decisive ending possible?

My friends, I present you No Time to Die.

I shall not specify which prediction was accurate.

Why would I? What fun would that be?

Yet know that every element works by itself and in conjunction with every other element. Know that the screenplay holds tightly enough together to make the usual Bondian plot gyrations—episodes and vignettes worthy of the best travelogues—seem necessary, urgent, and all of a piece. Know that the dialogue cuts and smarts and sparkles, thanks to old Bond hands Neal Purvis and Robert Wade, to newcomer Cary Joji Fukunaga (of True Detective and Beasts of No Nation fame), and, especially, to Phoebe Waller-Bridge (the writer-creator of two terrific television series, Fleabag and Killing Eve), whom Daniel Craig himself—with a meaty script already in hand—asked to provide a late-stage polish.

Know especially that the female characters are not merely Bond’s equals but, in some sequences, Bond’s betters. Know that, despite the carping of those insufferable online observers who embody the term “toxic masculinity,” No Time to Die is all the better for making most of its women into living, breathing human beings—not just conquests, bedpost notches, and hurdles for Bond to mount and surmount—most of the time.

Know that the movie is perfectly cast and that everyone brings his, her, or their best to each role. Jeffrey Wright makes a welcome return as CIA man Felix Leiter, last seen conferring with James Bond in 2008’s Quantum of Solace (Craig’s underrated sophomore outing as 007), to bring his friend out of the comfortable retirement in Jamaica he so evidently enjoys (to wit, Bond even lives in a house whose design and coastal location bear more than passing resemblances to Ian Fleming’s famous Goldeneye estate, the place where the author wrote all his Bond novels and short stories).

Yet Leiter’s mission to pull Bond back into spying happens five years after No Time to Die’s pre-credits sequence, itself set not long after the conclusion of 2015’s SPECTRE, which saw Bond bundle his lover Madeleine Swann (Léa Seydoux) into the famous Aston Martin DB5 and light out for the territories, leaving behind MI6, London, and the bad feelings provoked by his fight against terrorist mastermind Ernst Stavro Blofeld (an understated and gentlemanly Christoph Waltz).

Bond and Swann, we learn, have travelled to Matera, Italy to spend a lovely holiday together, yet demons from each lover’s past intrude. No Time to Die begins after the franchise’s patented gun-barrel dissolves and irises outward, showing a snowy landscape that sees a masked man walking across a Norwegian field, carrying a gun, and approaching a chalet that houses the young Madeleine Swann (Coline Defaud) and her alcoholic mother (Mathilde Bourbin).

This flashback’s violence is gripping, upsetting, and well-staged by Fukunaga, depicting in living color a traumatic story that Swann mentions in SPECTRE but that that film’s director, Sam Mendes, chose not to dramatize onscreen. Bond’s concern for Madeleine’s emotional equilibrium recalls his tenderness toward Vesper Lynd (Eva Green) in Casino Royale, and Craig plays these scenes with just the right balance of empathy and unease.

Seydoux is even better here (and throughout No Time to Die) than she was in SPECTRE, especially in another early Matera scene, where Madeleine refuses to share the full story of her troubled childhood until Bond visits Vesper’s grave, conveniently located in Matera, to put the past behind him. The emotional complexity, even sensitivity, of these interactions may seem unusual for a Bond film’s opening sequence, famous as they are for outrageously entertaining action set pieces, but, dear reader, don’t fret. When Bond visits Vesper’s grave, he finds her family crypt and says, in a line beautifully delivered by Craig, “I miss you.”

Then all hell literally breaks loose: a bomb explodes, leaving the battered, bruised, and bloody Bond believing that Madeleine has set him up for the kill. They escape Matera in a car chase that sees every gun and gadget in the Aston Martin used to such thrilling effect that this sequence recalls not merely the early Connery Bond films but also the absurd action fantasias of Roger Moore’s tenancy in the role, especially 1977’s The Spy Who Loved Me and 1979’s Moonraker.

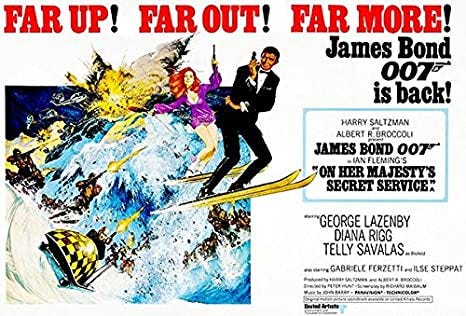

This trip to Vesper’s resting place also comes straight out of Fleming’s best Bond novel, his tenth, titled On Her Majesty Secret Service, which became, in 1969—thanks to screenwriter Richard Maibaum, director Peter Hunt, composer John Barry, and stars Diana Rigg and George Lazenby (in his only go-round as 007)—not merely one of the best movies in the Bond franchise, but among the best big-budget studio films ever produced in England.

Barry’s OHMSS score may be the finest of the eleven he wrote for the Bond movies, full of lovely melodies that range the emotional gamut from passion to whimsy to melancholy, while also including “We Have All the Time in the World,” probably the most beautiful song ever written for a Bond picture, sung to gravelly voiced perfection by jazz legend Louis Armstrong (this number, indeed, was likely the final song the ailing Armstrong recorded before his 1971 death).

Movie-composer extraordinaire Hans Zimmer replays snatches of Barry’s OHMSS orchestral music and strains from “We Have All the Time in the World” in his No Time to Die score, cementing this film’s debt to both the Fleming novel and the 1969 movie. More than that, as the 25th film in the series, No Time to Die includes references, allusions, and hat tips to each previous entry, doing so in thankfully subtler ways than did Die Another Day, the franchise’s 20th film (released in the 40th-anniversary year of 2002) that shoehorned excessive recollections of Bond’s cinematic past into its already-bloated storyline.

3. Far Up!

Yet enough about No Time to Die’s plot. Discovering its nooks and crannies, almost all of them welcome, is far more than half the fun for audience members who, like me, find the movie’s 2-hour-and-43-minute running time (the longest in franchise history) not to be an unendurable slog, but instead an expansive necessity that allows Fukunaga and his collaborators to tell the story they wish to tell. No Time to Die remains so grippingly paced that the sequences where it slows down for—gasp!—human communication are earned, welcome, and well played.

That’s a long way of asking what everyone really wants to know: How good is the cast? “Very good indeed,” is my reply.

Christoph Waltz returns as Blofeld, relishing his character’s world-spanning villainy in ways that he didn’t in SPECTRE. Blofled, having gone batty in the confines of his Belmarsh Prison cell, still manages to control his global criminal organization and still enjoys toying with Bond’s life in ways large and small.

The MI6 gang—agency head M (aka Gareth Mallory, played to the unctuous hilt by Ralph Fiennes), gadget-master Q (a terrific Ben Whishaw), office master Eve Moneypenny (an excellent-if-underused Naomie Harris), and Chief of Staff Bill Tanner (a fretful Rory Kinnear)—is in fine form, with Fiennes’s M taking a drubbing after Leiter and Bond uncover the existence of a nanotechnology weapon whose creation M has authorized and whose threat of global infection resonates—almost too uncomfortably—with our current pandemic woes.

This plot point proves once again that the Bond franchise, at its best, expertly plays upon real-world anxieties not merely to reflect, but sometimes to predict what will spook us a few years down the road. This movie, after all, wrapped principal photography on 25 October 2019, meaning that the Bond crew was ahead of the curve in fashioning a story about nanotechnology that can be deployed for murderous, even genocidal purposes.

My two favorite additions to No Time to Die’s cast are Ana de Armas as Paloma, a young CIA agent whom Felix Leiter deputizes to assist Bond during an expedition to Cuba, and Lashana Lynch as Nomi, a rising MI6 star who has not merely become a Double-Oh agent, but has been assigned Bond’s old code-number of 007. Yes, friends, No Time to Die makes good on the rumors that it would become the first film in the franchise to feature a Black Englishwoman as 007, a move that has happily driven racist online commentators to the point of near-madness (even if Nomi, who begins the film in a prickly relationship with her predecessor but who comes to enjoy a mutual respect with him, surrenders—in perhaps her character’s worst moment—the 007 appellation three-quarters of the way through the movie).

De Armas and Lynch are so good in their roles that I can only praise them. Daniel Craig reportedly requested de Armas’s involvement after starring with her in Knives Out, Rian Johnson’s fiendishly clever 2019 locked-room mystery movie (that has spawned its own franchise). If true, Craig’s insistence was among the wisest decisions made by No Time to Die’s production team. Although Paloma only appears onscreen for nine or ten minutes, the delightful de Armas makes each moment count. She participates in a fight sequence that sees her enthusiastic character, dressed in a beautiful-yet-skimpy dress, hold her own against all comers in witty, explosive, and stylish fashion.

Good as de Armas is here, her costume proves that, no matter how progressive Bond producers Barbara Broccoli and Michael G. Wilson may wish to appear, they still cannot resist the trope of seeing a beautiful woman kicking ass while dressed more revealingly than the tuxedoed Bond. De Armas handles every minute of her too-precious screentime so well that Paloma improves upon the character that she clearly references: Rosie Carver, Gloria Hendry’s newly minted CIA agent in Roger Moore’s inaugural outing as Bond, 1973’s Live and Let Die. Paloma is far more competent and far less duplicitous than Rosie, making me suspect that Phoebe Waller-Bridge created Paloma relatively late in No Time to Die’s long shooting schedule. If so, capital job, Ms. Waller-Bridge.

Lashana Lynch, so impressive as Monica Rambeau in 2019’s MCU movie Captain Marvel and as Arjana Pike in the British Sky One television series Bulletproof, transforms Nomi into a living, breathing character that Waller-Bridge’s reworking of No Time to Die’s female characters still mishandles. Some reviewers have claimed that Lynch and Craig don’t share much onscreen chemistry, but these observers are simply, fully wrong. From their first encounter, where Nomi plays into the sexual tension that draws Bond’s interest, to the moment when she kills one of the film’s subsidiary antagonists, the nanotechnologist Dr. Valdo Obruchev (David Dencik), by telling him “time to die” after he threatens to program the movie’s central nanoweapon to destroy entire ethnicities and races of people, Lynch’s charismatic toughness rivals that of James Bond himself.

Yet Lynch’s talent cannot overcome No Time to Die’s stereotypical treatment of Nomi. Gerald Early, in his jaundiced Common Reader dispatch “James Bond Rides Again,” makes the case against Nomi’s characterization (but not, he is careful to note, Lynch’s performance) by analyzing how the movie perpetuates sadly regressive ideas about Black women:

Her character is, by turns, the Black woman with a chip on her shoulder (when she first encounters Bond), the insecure, self-doubting Black woman (when she thinks she will lose the number 007 and be demoted), the humble Black woman who knows her place (when she offers to give Bond back the number), and the angry Black woman (when she kills the White scientist who threatens to kill Black people).1

Although I’d prefer to disagree with this litany, Early is dead-on in spotting No Time to Die’s objectionable treatment of Nomi. Only Lashana Lynch’s commitment to erasing the flaws of her character as written on the page salvages Nomi’s presence in the film, which offers its own sad commentary about the state of the Bond franchise’s racial paradoxes (the less said about Live and Let Die’s embarrassing attempts to merge the Bond formula with Blaxploitation themes, the better).

Considering that Black actresses have confronted this same, noxious Hollywood tradition for more than 100 years, No Time to Die’s production team should’ve done much, much better by Lynch, even if Gerald Early goes awry by claiming that Nomi adds nothing to the film. She works well enough thanks to Lynch, whose contributions to the movie shouldn’t be minimized, even by so intelligent an observer as Early. Notwithstanding his broadsides against “PC tokenism” and “the exploitation of Wokeness”2 that might’ve been penned by Tucker Carlson for one of his on-air meltdowns, Early’s gimlet eye powerfully assesses how No Time to Die mistreats Nomi.

I wish I could say otherwise.

That I can’t is a pity.

4. Far Out!

Yet what of the central antagonist, Rami Malek’s nattily named Lyutsifer Safin? Does the film do better by him? Malek, fresh off winning the Academy Award for his lead performance as Freddie Mercury in 2018’s Bohemian Rhapsody, signed up to become Craig’s final Bond opponent even though No Time to Die’s screenplay wasn’t finished, which might explain why Safin is simultaneously terrifying and underwhelming.

Fans of Malek’s breakout role as Elliot Alderson in Sam Esmail’s subversive television series Mr. Robot will be glad to hear that Malek continues to mine his wonderfully expressive face and vocal range to make Safin more impressive than Christoph Waltz’s version of Blofeld in SPECTRE and Mathieu Amalric’s Dominic Greene in Quantum of Solace, but less memorable than Mads Mikkelsen’s pitch-perfect Le Chiffre in Casino Royale and Javier Bardem’s inspired lunacy as Raoul Silva in Skyfall.

Safin looms over the entire film, from his first scene as the assassin who guns down Madeleine Swann’s mother to his final confrontation with James Bond, but remains offscreen for whole stretches of the movie, popping up here and there as necessary, which has led some critics—Matt Maytum of Total Film chief among them3—to wonder why, other than the substantial paycheck he no doubt negotiated, Malek would take a role that seems not to challenge him?

This perspective is wrongheaded. Malek’s slithery voice and unplaceable accent make Safin’s dialogue occasionally so faint that viewers may lean forward to hear him despite the sound system’s best efforts. Safin’s plot to program the nanoweapon with the genetic makeups of people he despises, particularly SPECTRE’s members, is mere prologue to his wish to cleanse the world of human beings who, to get through the day, endorse fantasies of personal rectitude, economic plenty, and political stability but remain so busy with the details of their quotidian lives that they’re unwilling to fight for the principles of fairness and equality that they espouse. Safin’s single conversation with Bond plumbs these issues, allowing Malek and Craig to verbally counterpunch one another with great aplomb.

If Safin reminds the faithful Bond viewer of any previous franchise villain, it is the very first: Joseph Wiseman’s titular Dr. No in the 1962 movie that started it all. Wiseman’s restrained portrayal of a man burning with contempt for people he sees as lesser than himself influences Malek’s performance in No Time to Die, as does the fact that Dr. No appears onscreen for only 20-or-so minutes, sharing one conversation with Connery’s 007 before moving onto his nefarious plans. No Time to Die’s creators intend longtime viewers to make this connection, right down to a villain’s lair that exists on a mysterious island hiding in plain sight and the antagonist’s physical differences from Bond (in Dr. No’s case, metal hands; in Safin’s, facial scarring).

This longtime Bondian convention—putative deformity or disability coding a character as depraved—is so far past its prime that we can only hope Barbara Broccoli and Michael G. Wilson drop it entirely from the next film. This tradition goes straight back to Ian Fleming’s novels, remains one of Fleming’s most objectionable narrative clichés, and, in a 2021 motion picture, rises to the level of rank ableism, as many disability activists have noted in their commentaries about No Time to Die.4

While we might expect Bond 25 to tick as many tropes off the franchise’s nostalgia checklist as possible, its creators can modify those traditions as they see fit, as they have by transforming the kittenish Bond Girl into the independent Bond Woman (see Madeleine—and even Moneypenny—for evidence). Quantum of Solace director Marc Forster wanted his movie’s primary antagonist, Dominic Greene, to have no visible physical blemishes or disabilities to make the point that true villainy (world-historical or otherwise) always carries a human face, so Bond 26 should take Forster’s lead and retire the deformed-villain motif once and for all.

5. Far More!

Thanks to the objections noted here, I understand why some viewers enjoy No Time to Die far less than I. Even an audience member as enthusiastic as myself must confess that, in the end, the film is a faulty masterpiece, or an imperfect masterpiece (aren’t they all?), or, perhaps, a near-masterpiece.

And yet. . . and yet. . . despite my misgivings (most especially Nomi’s characterization and Safin’s scars), No Time to Die remains a fascinating piece of work that, like Fleming’s final two Bond novels, creeps into my thoughts again and again no matter its problems.

No other Bond film has had the courage to re-create one of Fleming’s late, great narrative inventions, the poison garden that the literary Bond must infiltrate in Fleming’s penultimate 007 novel, 1964’s melancholy You Only Live Twice. Yet No Time to Die does, reassigning ownership of this toxic plant collection from the novel’s Blofeld to the film’s Safin.

Did you know, moreover, that Fleming was so frustrated with his famous character by the time he wrote You Only Live Twice that he tried to kill James Bond at the end of that novel? Fleming’s publisher, the stately book-house Jonathan Cape, so disliked this decision that Fleming’s longtime in-house editor, William Plomer, was able to persuade him to resurrect 007 for Fleming’s final Bond novel, 1965’s posthumously published The Man with the Golden Gun. As another flawed gem in Fleming’s late-stage authorial career, Golden Gun is bleaker than every other Bond book, full of grim portents about the inevitable disappointments and final passage to death that bedevil all human beings.

No Time to Die doesn’t repeat this pattern even if Safin’s poison garden is one of the movie’s two major appropriations from the literary You Only Live Twice (I refuse to reveal the second here). Despite a willingness to dip into gloom now and then, the film settles upon a tonal paradox best described as melancholic hope (or, perhaps, hopeful melancholy) that Léa Seydoux’s excellent work as Madeleine Swann captures, but that requires Daniel Craig’s performance as Bond to sell perhaps the most surprising development in the cinematic character’s history.

And sell it he does. So good is Craig at revealing Bond’s emotional complexity—his toughness, his empathy, his humor, and his regret—that the actor equals his achievement in Casino Royale and, by No Time to Die’s conclusion, surpasses even that high bar.

Craig’s final moments as James Bond are surprising, beautiful, even magnificent. No Time to Die extends the character an unexpected grace not seen since those final, shattering minutes of 1969’s On Her Majesty’s Secret Service. I’m firmly in the camp of observers calling for Craig to receive an Academy Award nomination as Best Actor, even if the chances of this happening are about as likely as the possibility that Barbara Broccoli and Michael G. Wilson will ask me to play James Bond in the next movie.

Craig may have been nominated for the British Academy of Film and Television Arts Award’s (BAFTA’s) Best Actor prize for Casino Royale way back in 2007 (and Rami Malek can say ad nausem how surprised he will be if Craig is not tapped for the Academy Award5), but the Oscars don’t consider Bond movies to be worthy of acting, directing, and writing nominations (the so-called “creative” awards), instead relegating them to “technical” categories (as if editing, sound mixing, and effects work are any less creative). So I have my doubts about this nomination—no matter how well-deserved—ever coming to pass.

I could be wrong.

I may well be wrong.

Yet I don’t think I’m wrong.

Let’s not, however, carp about matters of little consequence. No Time to Die is among 2021’s best films, making for a walloping good time at the movies that’ll make you think, make you feel, and may even, if you’re an old softie like me, make you cry. Bidding farewell to Daniel Craig’s tenure as James Bond may not be easy considering that he’s played the role for a longer continuous timespan than anyone else (16 years, beating Roger Moore’s 12 years, although Moore starred in two more Bond films than Craig), meaning that whomever inherits the role of James Bond from Craig (come on, Idris Elba!) has an enormous challenge ahead of him.

Unless producers Broccoli and Wilson have something unexpected waiting in the wings for the film franchise’s 60th anniversary in 2022, who knows exactly when we might see that person step into Bond’s tuxedo? I can’t say, but I was happy to see, as viewers who remain seated until the very, very end of No Time to Die’s final-credits sequence shall observe, those words that have reassured generations of 007 fans: James Bond Will Return.

That cannot come quickly enough.

So, to invoke a dictum heard throughout the 25 movies that’ve already graced our screens: Hurry, Mr. Bond.

NOTES

Gerald Early, “James Bond Rides Again,” The Common Reader, 18 October 2021,

https://commonreader.wustl.edu/james-bond-rides-again/.

Ibid.

Matt Maytum, “No Time to Die Review: A Fitting End to Daniel Craig’s Tenure as

James Bond,” Total Film, 28 September 2021, https://www.gamesradar.com/no-

time-to-die-review-james-bond/.

See Trish Rooney’s 11 October 2021 Salon.com article “James Bond Hasn’t Changed

Much, and Neither Have His Problematic Villains after 25 Films”

(https://www.salon.com/2021/10/11/james-bond-villain-no-time-to-disfigurement-

disability/) for a detailed exploration of this topic.

In addition, Jen Campbell’s 2017 YouTube video “Let’s Talk: Villains &

Disfigurement” offers fascinating commentary about this issue.