All the Way with JFK

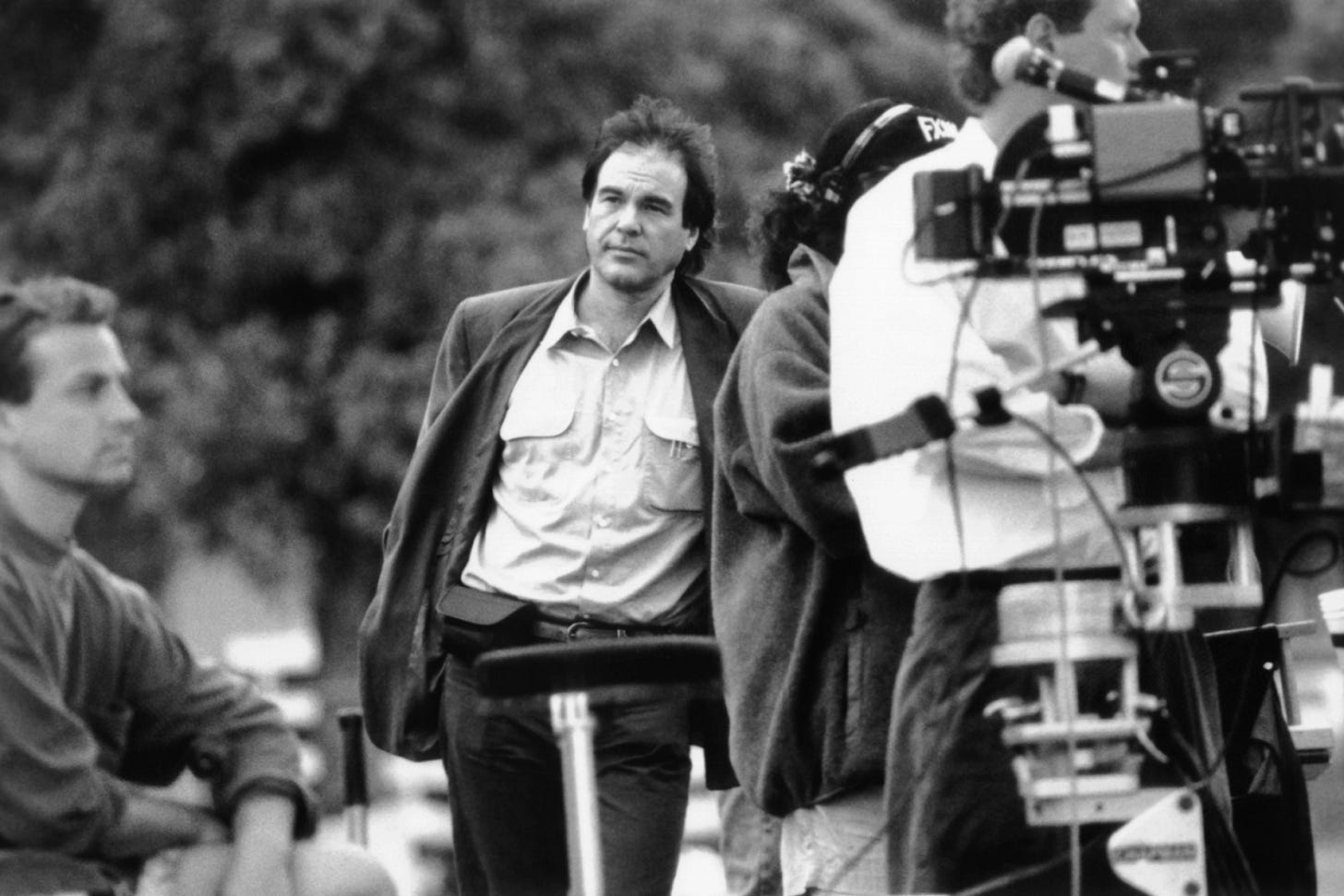

Thirty years later,* the rabblerousing conspiracy thriller remains a signature achievement for Oliver Stone.

*Note to The Vestibule’s subscribers: I prepared this long essay about Oliver Stone’s 1991 film JFK soon after seeing it (for the 25th-or-so time) on HBO Max one Sunday afternoon in late October 2021.

I hadn’t intended to watch Stone’s controversial masterpiece, but found it atop my HBO Max channel’s “Top Recommendations List” via my Apple TV device, whose algorithm organizes these selections based on past viewing choices, meaning that watching both of Stone’s 1986 movies—Salvador and Platoon—the preceding week made JFK an inevitable computerized suggestion.

Realizing that 2021 was the film’s 30th anniversary, I waded into the following article with no real idea about where it would go—pounding out the first few paragraphs one or two days after seeing JFK for the first time in four or five years—or where the finished piece would land.

Washington University in St. Louis’s The Common Reader: A Journal of the Essay is always my go-to choice thanks to the generosity of Editor-in-Chief Dr. Gerald Early and Managing Editor Ben Fulton, but I knew this essay was much too long for their preferred-length requirement and didn’t want it cut down to size, no matter how advisable doing so was, is, and may have been.

The manuscript came together over three or four weeks, in fits and starts while pursuing other projects, before reaching what seemed its natural conclusion. Then, in the hurly-burly of whatever else occupied my attention at the time, this article went onto the back burner and stayed there until JFK came around again, recommended to me by Amazon Prime Video last week.

So, despite this essay having missed JFK’s actual 30th anniversary, I dusted off the manuscript and offer it to you now, in June 2022, as an example of how my sabbatical from university teaching has lead me down all sorts of unexpected, yet pleasant, byways whose paths I’ve been happy to follow.

Despite being long, chatty, and cantankerous, I hope you find this piece an enjoyable trip back in time, when Oliver Stone and his collaborators helped jumpstart the 1990s’ zeitgeist for conspiracy thrillers by reviving a cinematic genre that’d been popular during the 1970s, but had waned somewhat during the 1980s, with what remains one of my favorite American movies, warts and blemishes and all.

—All the best, Jason

1. Hopes & (Fever) Dreams

Roger Ebert begins his retrospective “Great Movies” review of Spike Lee’s 1989 cinematic classic this way: “I have been given only a few filmgoing experiences in my life to equal the first time I saw Do the Right Thing. Most movies remain up there on the screen. Only a few penetrate your soul. In May of 1989 I walked out of the screening at the Cannes Film Festival with tears in my eyes.”1

Ebert’s response mirrors my own to seeing Lee’s remarkable film (in June of 1989, not in Cannes, France, but in Mountain Home, Arkansas) and, moreover, matches my reaction to seeing Oliver Stone’s JFK, in December of 1991, at the Ridgeway Four Cinema in Memphis, Tennessee. I attended JFK on opening night, seeing it with a college chum who remains a dear friend. We sat amongst an audience that, like me, remained rapt for JFK’s 189 minutes, so rapt that, with rare exceptions, not a syllable was uttered during its three-hour running time.

JFK proved so compelling, so gripping, so all-encompassing that I lost track of where I was. For whole stretches of the film, I forgot that I was sitting in a seat in a movie theatre amidst other people. JFK had somehow absorbed me into its onscreen dramatization of New Orleans District Attorney Jim Garrison’s (Kevin Costner’s) investigation into the 1963 assassination of President John F. Kennedy, penetrating every part of my mind and soul to gift me the same experience that Do the Right Thing had awarded Ebert (and myself) 18 months earlier.

I shall never forget the sensation of time jumping forward when JFK’s final credits rolled. I was shocked—not mildly surprised or pleasantly befuddled, but fully stunned—to realize that three hours had passed, for it seemed I’d just sat down, John Williams’s splendid music had just started, the first frame had just rolled, Martin Sheen’s voiceover had just begun offering Oliver Stone’s capsule version of American political history during the 1950s and the 1960s, a clip of President Dwight D. Eisenhower’s 1961 Farewell Address to the Nation had just played, Eisenhower’s warning against allowing the military-industrial complex to “endanger our liberties or democratic processes” was still ringing in my ears, and this film couldn’t possibly be finished, could it?

Those sensations converged to create the same experience that Do the Right Thing had. As an avid moviegoer, I was familiar with the feeling of getting lost in a film, just as I, an avid reader, was accustomed to getting lost in the pages of a book, but JFK riveted me so totally that, thirty years later,* I can still recall that evening in, well, cinematic detail. The fever dream into which JFK plunged me is noteworthy not simply because it happened to one person, but because it was a collective experience. My friend Eric said much the same, as did nearly every other member of the audience that night, or at least those within earshot, whose conversations erupted all around us as we shuffled outside into the crisp December air.

I remember wondering if this was what epiphanies were: a glimpse of something larger and more profound than myself, a private and silent sense that the world worked in ways I’d not anticipated but that I now understood better than before, totally unlike the cheap revelations sold by televangelists like Jim Bakker and Jimmy Swaggart during their unhinged scream-sermons.

Isn’t this, I thought, what art of any kind is supposed to do, namely fuse cognition, emotion, hope, and truth so fully that distinguishing them is not merely impossible but also inadvisable?

If, as Oliver Stone had claimed in countless press interviews, he hoped his film would provoke people to think about American history differently than they had before, then JFK had done its work.

2. Highs & (B)lows

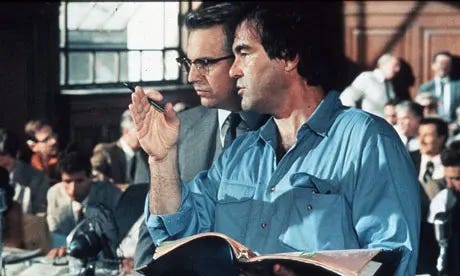

JFK wasn’t, of course, a one-man production. Referring to it as Oliver Stone’s movie elides the hundreds of people who labored tirelessly to bring the film to life, from its talented cast and co-writer Zachary Sklar—who helped shape Stone’s unruly first draft into a screenplay of tremendous detail, density, and power—to cinematographer Robert Richardson plus co-editors Joe Hutshing and Pietro Scalia, all three of whom won Academy Awards for their efforts. The movie includes nearly 125 speaking roles, which gives some sense of the production’s scale as well as the near-lunacy that Stone and his collaborators demonstrated by undertaking such a mammoth project.

The Kennedy assassination had formed the basis of innumerable books, magazine articles, newspaper exposés, and feature films, to say nothing of television episodes and movies-of-the-week, but JFK occupied a different class.

Stone intended to prosecute a case not simply about Kennedy’s public murder in Dallas, Texas on 22 November 1963, but about how this assassination helped to unmoor the United States of America from any remaining ties to the democratic ideals that the writer-director had come to cherish after surviving combat in the Vietnam War, an experience that shook Stone’s faith in the republic so profoundly that he became a patriot in the same sense that Martin Sheen avows during a 2003 episode of James Lipton’s Inside the Actors Studio: “I love my country enough to risk its wrath by drawing attention to the negative things we don’t always want to see.”2

Wrath is only one of the responses that Stone and his film drew. JFK provoked vitriol from Beltway pundits, newspaper columnists, establishment politicians, and mass-media commentators across the ideological spectrum even before the movie began shooting, although the production collected just as many defenders during this same timespan. Stone and Zachary Sklar, a freelance journalist who’d helped edit Jim Garrison’s 1988 book On the Trail of the Assassins (one of the two sources upon which they based their script, the other being Jim Marrs’s 1989 bestseller Crossfire: The Plot that Killed Kennedy),3 had conducted voluminous research into the assassination’s extensive literature, itself a fever swamp of legitimate investigations, intelligent analyses, crackpot speculations, and unhinged mutterings that Stone’s and Sklar’s screenplay captures in its overheated, surreal, and compelling pages.

The subsequent film matches its script’s jangled fusion of settled history, fervent conjecture, informed scholarship, and political derangement so well that watching JFK approximates the experience of being mugged by a group of hooligans after escaping a bar brawl in which everyone throws punches, glassware, and furniture at everyone else. The film’s relentless pace generates a spell so hypnotic that viewers—grasped tightly by JFK’s narrative power from its first moment to its last—become willing participants in historical dramatizations that prod, provoke, and unsettle their recipients no matter how sympathetic or hostile they may be to Stone’s and Sklar’s project of questioning every bit of received wisdom about the assassination, as well as this mission’s inevitable corollary: upending every conventional truth about post-World War II American life.

In what may be its greatest triumph, JFK doesn’t perplex its audience despite including more information-per-minute than just about any other American movie of any era. By choosing as their centerpiece Garrison’s 1966 investigation into Kennedy’s assassination and the resulting 1969 criminal prosecution of New Orleans businessman Clay Shaw (Tommy Lee Jones) for Kennedy’s murder (the only such trial ever brought in response to this event), Oliver Stone and Zachary Sklar adapt perhaps the tried-and-truest mass-media genres of all, the police procedural and the courtroom drama, into a spellbinding examination of American history, political intrigue, and domestic unrest that flings so much data at audience members that only confusion should result.

Yet, instead, JFK makes a clear-eyed case that Kennedy’s assassination resulted from vast and entrenched economic, political, and military forces that combined to pursue the narrow objective of removing Kennedy from power when both his foreign and domestic policies started seeming too dovish for the moneyed interests so heavily invested in anti-Soviet mania (and the perpetual war machine created in its wake)—intelligence agencies, defense contractors, their bankers, and their friends in the highest echelons of the American armed forces—that they took rumors about Kennedy’s plans to end America’s aggressive opposition to the Soviet Union if he won a second term in office so seriously that they decided this consequence could never, should never, and would never come to pass.

As Cold War fever dreams go, this one was hardly novel, or even terribly controversial, given its currency among commentators who bolstered the Kennedy-Camelot myth that saw the 35th president as the harbinger and chief representative of a new age of openness, renewal, vitality, and liberation after the self-imposed restraints (cultural, economic, political, and sexual) of the World War II era and the stultifying conventionalism of the Eisenhower-Nixon years that followed.

The Forties and Fifties germinated the flashpoints for which the Sixties became not merely famous but also, for political conservatives, infamous. As a decade of economic, racial, sexual, and religious turbulence, the Sixties saw the Civil Rights Movement, the Women’s Rights Movement, the Sexual Revolution, the nascent Gay Rights Movement, and, perhaps most notoriously, the antiwar movement all combine to shake the foundations of American society just as the long-promised prosperity of the postwar years was becoming the birthright of white Americans.

These privileged citizens’ middle-class strivings powered Jim Crow segregation, white flight to the rapidly growing suburbs, and a pestiferous anti-Semitism (that defined Jewish Americans as civic outcasts) just as feminists’ demands for equality between the sexes became more pronounced; just as civil-rights protestors’ calls to cleanse every corner of the nation of its racial-caste system became relentless; and just as antiwar activists’ vociferous demands to end America’s imperialist invasion of Vietnam migrated from college campuses, prayer circles, and coffee klatches to the streets of every major city.

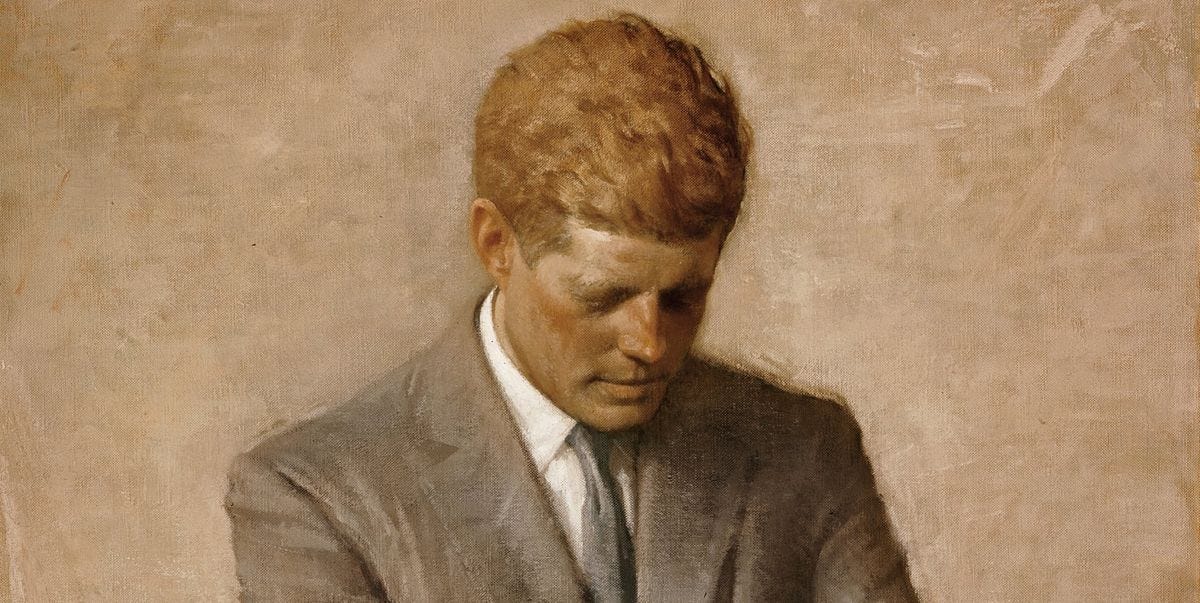

Kennedy became an avatar of this vigorous questioning of the nation’s traditions even if his actual presidency worked to defend those traditions as often as it contravened them. That the actual JFK couldn’t live up to the dreamy images created by himself, his administration, and his press corps was itself part of the appeal. No matter how gun-shy Kennedy seemed when it came to providing full-throated assistance to the Civil Rights Movement, for instance, his rhetorical support for its broadest principles stood him in sharp contrast to the virulently racist pronouncements of Southern senators and representatives from both parties.

Indeed, Kennedy’s public statements, policies, and actions in this regard strengthened during his time in office, so much so that, in response to the courageous demonstrations by civil-rights protestors all over the nation, he sent federal marshals to protect Freedom Riders during the summer of 1961; federalized National Guard troops to ensure that Black students were integrated into the Universities of Mississippi (in 1962) and Alabama (in 1963); gave a powerful speech about the moral, civic, and constitutional dimensions of the freedom movement on 11 June 1963; and drafted comprehensive civil-rights legislation that wouldn’t be passed by Congress until after his death but that we now know as The Civil Rights Act of 1964 (and that paved the way for The Voting Rights Act of 1965).

Kennedy’s sometimes shockingly get-tough approach to Soviet Communism, likewise, helped provoke the Cuban Missile Crisis of October 1962 that the president and his brother, Attorney General Robert F. Kennedy, cleverly claimed credit for defusing just as the United States and the Soviet Union stood on the brink of thermonuclear warfare. Despite their dislike of one another, JFK and Vice President Lyndon B. Johnson were master communicators with the hype man’s talent for seizing upon any issue, topic, or controversy and then spinning it their way.

They were aided in this quest by a coterie of admiring pressmen who chose to hide each man’s extramarital dalliances alongside their extrajudicial attacks against leftist movements and leaders all over the globe, with none more galling to them than Cuban Prime Minister Fidel Castro’s successful Communist revolution on an island 90 miles from Florida’s shores. Despite conservative backlash against Kennedy’s supposedly soft stance on Communism, Seymour M. Hersh’s 1997 book The Dark Side of Camelot, Maurice Isserman and Michael Kazin’s 2000 book America Divided: The Civil War of the 1960s, Thomas G. Paterson’s 1989 edited anthology Kennedy’s Quest for Victory: American Foreign Policy, 1961-1963, and Garry Wills’s 1982 book The Kennedy Imprisonment: A Meditation on Power—among many other sources—document that Kennedy was anything but.4

This thumbnail history overlooks many nuances and complications in Kennedy’s personal and political lives (Kennedy, for instance, was reportedly furious when the Central Intelligence Agency helped assassinate freely elected Congolese Prime Minister Patrice Lumumba in the days before Kennedy’s 1961 inauguration, JFK having offered strong support for African decolonization partly as a way to counter the expansion of Soviet Communism and partly as a way to signal his seemingly genuine opposition to all forms of imperialism across the continent), to say nothing of the complex welter of economic and political forces that affected everyday Americans during the Forties, Fifties, and Sixties.

This quick historical review shouldn’t also suggest that Kennedy was simply a shallow media creation whose international image as a different sort of leader was entirely false. Kennedy, like all American presidents before and after him, broke with some policies of his predecessors while maintaining others, but Oliver Stone and Zachary Sklar perpetuate the myth of JFK’s Camelot as much as they tarnish it in JFK.

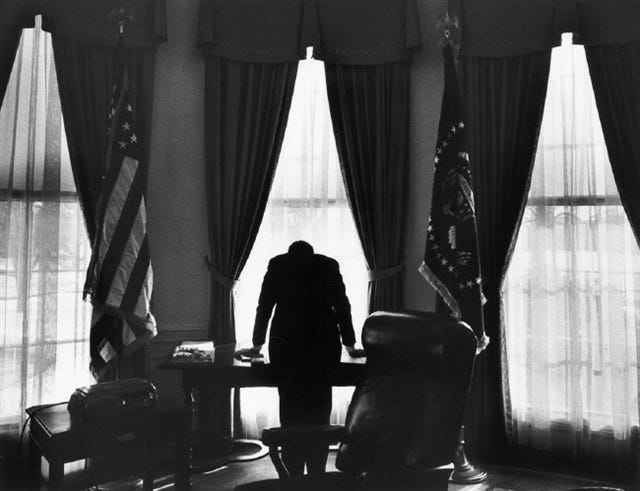

This oscillation has the salutary effect of whipsawing viewers among many conflicting versions of Kennedy the man, Kennedy the myth, Kennedy the president, and Kennedy the legend, rendering their choice to show Kennedy only in documentary footage (or footage cleverly goosed by the production team to appear authentic, whether still images or over-the-shoulder and behind-the-back views of doubles that are dead ringers for Kennedy’s build and body language, plus newsreels and home movies that appear for all the world like they were shot during the Sixties—and everything in between) a brilliant creative choice.

Kennedy is central to JFK but not the center of JFK. He remains elusive, just off-stage yet ever-present in each viewer’s mind, to achieve an aloof intimacy whose paradoxical effect helps the film masterfully—and even magnificently—re-create the Sixties as a shifting series of ciphers, facts, fictions, and details that one can never quite pin down.

That, if nothing else, helps JFK conspire to demolish the shibboleths about American exceptionalism that Oliver Stone and Zachary Sklar have no time to countenance.

3. Rights & Responsibilities

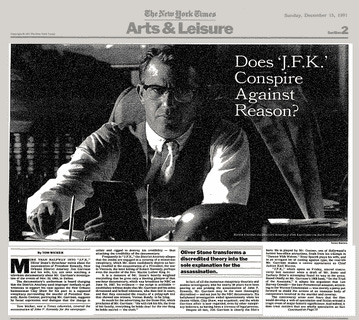

Conspire is a loaded verb to employ given JFK’s existence as one of the 1990s’ two greatest mass-media conspiracy thrillers (the other is a nifty little 1993 television series created by Chris Carter titled—perhaps you’ve heard of it?—The X-Files). The fusillade of invective that JFK drew from the Beltway press—or what longtime White House correspondent Helen Thomas once called “the chattering classes” and New Republic editor Michael Tomasky (among others) once dubbed “the chatterati”—after a copy of Stone’s first-draft screenplay was leaked to Washington Post investigative journalist George Lardner, Jr. was, then and now, unprecedented for a motion picture that had not put even one frame of film in the can.

The notion that factions within the American government colluded with anti-Castro Cuban refugees, right-wing militias, paramilitary hate groups, the Mafia, and even Lyndon B. Johnson to murder an American president (all theories explored by the fictionalized Garrison and his investigative team in JFK) was so objectionable to people like Jon Margolis, Tom Wicker, George F. Will, and even Alexander Cockburn that they mounted sustained press campaigns to discredit Oliver Stone and his film in the op-ed pages, metro sections, and cultural-affairs pages of the nation’s leading daily newspapers; in commentaries, satellite link-ups, and studio interviews for the nation’s nightly news broadcasts; and in articles, essays, and letters-to-the-editor for the nation’s weekly newsmagazines.

This tide of “who-does-he-think-he-is?” reproach swamped the shores of American journalism so frequently during the days, weeks, and months of 1991 that the public couldn’t avoid reading, watching, and hearing about JFK’s supposed assault on good taste, political propriety, and, in the harshest assessments, history itself. This crusade inevitably raised the movie’s profile so high that it was guaranteed a massive audience come its December 1991 release, so much so that my college roommates and myself indulged a conspiracy theory of our own, namely that Stone and the studio were in cahoots with their critics to give JFK more free advertising than any Hollywood production since the days when Harry Cohn, Louis B. Mayer, David O. Selznick, Irving Thalberg, and Jack Warner orchestrated press promotions so pervasive that even people who stayed indoors couldn’t avoid them.

JFK, predictably, was a big hit, but not simply because Oliver Stone was wily enough to ride the controversy his film provoked to box-office gold. JFK is a stunning achievement in cinematic narrative that builds on the blunt power of its writer-director’s previous work—particularly 1986’s Salvador and Platoon, 1989’s Born on the Fourth of July, and 1991’s The Doors—to construct a fascinating story about the Kennedy assassination as proxy for America’s decline and fall, alongside Stone’s and Sklar’s dissatisfaction with what they perceive as the nation’s rightward political turn, as forcefully as any movie, television series, novel, or other cultural work I know.

The film is chock-full of fabulous performances by actors escaping their usual roles. The late-great Ed Asner, as proud a Hollywood liberal as ever lived, plays W. Guy Banister, a John Birch Society member and former FBI agent working as a private investigator in New Orleans so regressive in his views that Jim Garrison jokes that he (Banister) is “slightly to the right of Attila the Hun.”

The late-great John Candy, a gifted comic known for his physical comedy as much as his talent at dialogue, plays Dean Andrews, a shucking-and-jiving New Orleans attorney hired to help Lee Harvey Oswald (Gary Oldman) upgrade his Marine Corps discharge from “undesirable” to “honorable,” as well as a man who speaks an argot so distinctively confounding that, when Garrison loses patience with Andrews’s circumlocutions during a midday luncheon, relief is the only possible response.

The late-great Walter Matthau, a born-and-bred New Yorker from the Lower East Side, plays Louisiana Senator Russell B. Long as an aw-shucks, down-home straight talker who, sitting next to Garrison during a 1966 airplane flight to Washington D.C., expresses so many doubts about the findings of the Warren Commission’s official investigation into Kennedy’s assassination that he inadvertently sets Garrison on the hunt that will consume him for the rest of the movie.

And Joe Pesci, a spitfire actor coming off his Academy Award-winning performance as the unhinged, hypermasculine Mafia goon Tommy DeVito in Martin Scorsese’s 1990 masterpiece Goodfellas, plays David W. Ferrie, a gay pilot whose memorably profane dialogue (Pesci utters more variations of the word fuck than he does even in Goodfellas, an accomplishment unto itself) allows him to play a man who hates Kennedy so intensely that, at several points in JFK, you half-expect Ferrie/Pesci to fly apart at the seams, only to see Pesci’s face, voice, and body language collapse into themselves during touching moments of self-doubt, -recrimination, and -criticism that create the unforgettable portrait of a bizarre man in profound spiritual, emotional, and physical distress.

Oliver Stone, no matter his dictatorial ways on set, gets terrific performances out of his gargantuan cast, including Kevin Costner, who plays Jim Garrison as the dignified descendent of Jimmy Stewart’s Senator Jefferson Smith in Frank Capra’s 1939 battle-cry against political corruption, Mr. Smith Goes to Washington.

Costner’s Garrison may be more jaded than Smith, particularly as Garrison’s investigation into Kennedy’s murder reveals wave after wave of political dirty tricks that expose America as a cesspool of violence, racism, misogyny, and sleaze aided and abetted by its security services’ interest in preserving their own power at the expense of everyday democracy, but he’s also a man who fervently wishes to believe in those seemingly naïve paeans to truth, justice, and the American way on which he (and JFK’s viewers) were raised.

In JFK, the CIA, the FBI, members of the Joint Chiefs of Staff, and, in one memorable exploratory scene that the former president’s admirers considered slanderous, even LBJ himself emerge as willing accomplices to Kennedy’s assassination, demolishing all remaining faith in America as the land of the free and the home of the brave.

Costner, who appears in nearly every moment of JFK, nicely shoulders the burdens of keeping its cinematic ship upright even when the movie threatens to capsize under the weight of its own rabid suppositions. JFK’s feverish race through the dark places of 20th-Century American history eventually runs headlong into the pedestrian reality that the United States is not nearly as grand a citadel of freedom as its national mythology suggests, but that Garrison, a decorated World War II combat pilot who keeps a Nazi helmet in his office to remind himself about the stakes of submitting to tyranny, keeps hoping against hope can be reversed into a new flowering of civic rectitude before his country falls victim to the nightmarish realities of corruption and neo-fascism that, Garrison fears, now lurk inside America’s fundamental institutions.

Even Costner’s dodgy attempt at a Southern accent cannot distract from his ability to project Garrison’s fundamental decency and consequent distress at discovering his nation to be less noble than expected, although Costner’s New Orleans brogue is more successful than his widely derided faux-English accent in an earlier 1991 film, Kevin Reynolds’s Robin Hood: Prince of Thieves. Costner even works himself into a fair approximation of Jimmy Stewart’s moral outrage during Jefferson Smith’s filibuster at the end of Mr. Smith Goes to Washington.

Costner/Garrison, indeed, commands the screen during JFK’s final courtroom trial, saying at one point, “Let’s just for a moment speculate, shall we?” before talking almost uninterrupted for 22 minutes as he weaves the strands of the assassination’s many schemes into an agile narrative that culminates in Garrison going frame-by-frame through the now-famous Zapruder film (the home movie shot by Dallas dressmaker Abraham Zapruder from Dealey Plaza’s Grassy Knoll that offers the best photographic evidence of Kennedy’s murder), leaving both JFK’s characters and viewers feeling bludgeoned by the sight of the president’s head blown open, pitching his body “back and to the left” in a phrase that Garrison repeats four times until this sickening mantra burrows its way into our conscious and unconscious minds.

Even more impressive than Costner’s work as Garrison is Tommy Lee Jones’s Oscar-nominated performance as the refined and elegant Clay Shaw; Sissy Spacek’s efforts as Garrison’s put-upon wife, Liz, (so good is Spacek that she overcomes the screenplay’s deplorably sexist depiction of her as a nagging wife and mother who excoriates Garrison’s obsession with solving Kennedy’s murder at the expense of his domestic responsibilities); and Gary Oldman’s terrific turn as Lee Harvey Oswald, a performance of such accuracy that watching footage of the actual Oswald reveals how well Oldman nails the man’s vocal inflections, body language, and gait.

Then there’s Donald Sutherland’s spectacular work as a character known only by the moniker X (or Mr. X), a retired Pentagon adviser based on L. Fletcher Prouty—the Joint Chiefs of Staff’s Chief of Special Operations during Kennedy’s administration—who lays out, in a remarkable 16-minute monologue, all the reasons to doubt the Warren Commission’s official pronouncements about Oswald being the lone gunman and all the reasons to believe that Kennedy posed a threat to the power players at the heart of America’s intelligence services.

Sutherland’s acting is so clear, clean, and commanding that viewers can easily take everything he says as gospel truth, but just as remarkable is how Sutherland transforms dialogue that comes close to pure exposition—i.e., the sort of information-dump that I advise screenwriting students to avoid at all costs—into a speech so enthralling that viewers, upon later reflection, realize how well Oliver Stone and Zachary Sklar weave X’s words into a disquisition that smacks of authentic received wisdom, with X’s observations that “kings are killed”; “politics is power, nothing more”; and “fundamentally, people are suckers for the truth, and the truth is on your side” becoming chestnuts that, no matter how expository, also function as exceptions that prove the rule.

4. Truths & Falsehoods

Needless to say, JFK so capably demolishes its viewer’s faith in the Warren Commission’s conclusions (namely, that Lee Harvey Oswald was the lone assassin and that no conspiracy existed to murder America’s 35th president) that accepting them may seem impossible after watching Stone’s movie. The Commission’s 26 volumes and supporting evidence are available at the National Archives and the U.S. Government Information (GovInfo) websites, so please peruse them at your leisure to locate the deficiencies that Oliver Stone and Zachary Sklar, through their cinematic surrogate Jim Garrison, spotlight throughout JFK’s 189 minutes.

Accepting this challenge doesn’t necessarily vindicate any of Stone’s and Sklar’s theories about who killed Kennedy or why. Doing so will also reveal that some of the Commission’s missteps, as recounted in JFK, resulted from the imprecise methodologies that seem endemic to American investigatory procedures and the bungled application of said practices that seems universal throughout American law enforcement, but, by the same measure, ignoring Stone’s and Sklar’s pessimistic reading of the Kennedy assassination and mid-20th-Century American history seems equally perilous.

By 1991, few American viewers (myself included) needed much prodding to be convinced that their governments (local, state, and federal) lied to their citizens as often as they told the truth. After the manifold failures of Vietnam, the protracted constitutional crises of Watergate, the ongoing economic dislocations produced by massive de-industrialization, the persistent racial disparities that the Reagan years exacerbated, the endless examples of municipal corruption covered in every local newspaper, and the farce of prosecuting a “necessary war” against Iraqi aggression in Kuwait (that became one more misstep in America’s seemingly unquenchable thirst for empire building), the cynicism that Stone was accused of fostering with JFK was easy to adopt, particularly for college students getting their first real exposure to the knotty, perilous, and objectionable facts about the United States’s behavior at home and abroad, facts that didn’t—and don’t—align with the virtuous stories Americans love to tell themselves about their country’s nobility, righteousness, and beneficence.

That properly dispiriting outlook helps explain why JFK struck myself (and audiences of all ages) both as revelatory and as validation that the world was less welcoming than we hoped in our most innocent moments. Stone’s film gives American audiences permission to nurse their doubts about the official histories force-fed them in elementary-, middle- and high-school classrooms while suggesting, to everyone else, that such pablum is impossible to swallow, much less digest.

Although official upholders of America’s national mythology still maintain that many of Oliver Stone’s and Zachary Sklar’s doubts are unreasonable, watching JFK thirty years later* demonstrates that the movie disconcerts these functionaries even today because, despite its paranoid hearsay about who had motive to assassinate John F. Kennedy, JFK brilliantly stitches together an astonishing number of facts, fictionalized re-creations of actual events, and outright fantasies about what might have happened that day in Dallas to destabilize easy faith in the American dream, however one defines it.

Plus, JFK’s warnings against the erosion of democratic ideals are difficult to ignore as continuing revelations about the Trump regime’s four-year assault on governmental institutions and on the concept of truth itself pile up, onslaughts culminating in a coup attempt that, by trying to overturn the results of 2020’s presidential election, incited on 6 January 2021 a riotous insurrection at the United States Capitol Building in Washington, D.C.

The open-eyed skepticism that Jim Garrison manifests by JFK’s final scenes provokes a compensatory peroration on his part that urges the jurors sitting in judgment of Clay Shaw (and the audience members watching the film) to remember that “the truth is the most important value we have,” a speech in which Garrison quotes everyone from American naturalist Edward Abbey to the English poets John Harington and Alfred, Lord Tennyson, as well as Adolf Hitler himself (about telling a lie so colossal that, the more people hear it, the more they’ll believe it).

Costner/Garrison gets so worked up during his final statement to the jury/audience that, as David Ansen notes in his admiring 22 December 1991 Newsweek review of JFK, this display is “a 90-proof Capraesque barn raiser, down to the Jimmy Stewart catch in Costner’s throat.”5

Ansen’s review is one of the many articles, essays, and screeds about JFK available in Stone’s and Sklar’s published movie script, JFK: The Book of the Film: The Documented Screenplay. This volume, released by Applause Books in early 1992, not only includes the final draft of their screenplay but also extensive annotations that include Stone’s and Sklar’s research notes, which explain their reasoning for even small creative choices that, as often as not, offer effective rebuttals to their many detractors.

This 593-page book is even more valuable as a time capsule of the American political press circa 1991 by compiling no less than 101 responses to the movie’s production and ensuing controversies, ranging across the continuum of reactions (from frank admiration to appalled condemnation), all arranged in chronological order, beginning with Jon Margolis’s 14 May 1991 Chicago Tribune article “JFK Movie and Book Attempt to Rewrite History” and concluding with a series of five letter-essays published in The Nation magazine’s 18 May 1992 issue.

This tome, despite its length, is a marvelously informative read that reveals just how powerful a cultural force cinema—and, occasionally, one specific film—can be. JFK certainly qualifies, in David Ansen’s words, as a barn raiser, but the movie’s also a barnburner whose take-no-prisoners approach to Kennedy’s assassination makes it a vital, vibrant, and necessary movie even thirty years* after its premiere.

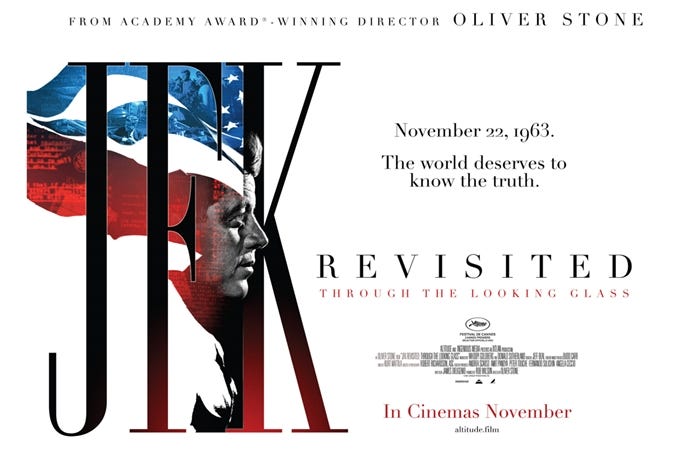

Oliver Stone (unsurprisingly) agrees with this perspective, having released on 12 November 2021 a documentary titled JFK Revisited: Through the Looking Glass that first opened at the 2021 Cannes Film Festival; that is narrated in different parts by Stone, by Whoopi Goldberg, and by “Mr. X” actor Donald Sutherland; and that examines documentation declassified in the decades since Stone unleashed JFK on the world. As a direct result of his 1991 movie’s impossible-to-ignore charges that Lee Harvey Oswald couldn’t have been the lone assassin and that, by implication, only a conspiracy explains how an American president was gunned down in broad daylight while surrounded by Secret Service agents, Congress decided to act.

So yes, it’s true, as Stone says in JFK Revisited, that JFK helped inspire passage of The President John F. Kennedy Assassination Records Collection Act of 1992, a law that established an independent federal agency named the Assassination Records Review Board (ARRB) to consider all documents pertaining to Kennedy’s assassination that had been classified top secret and beyond, then locked away from public scrutiny until at least the year 2029 and, in some cases, the year 2038 (or later).

ARRB did its work so well that, as of April 2018, most documents had been declassified and made available for review at the National Archives, although as many as 20,000 were still at that point partially redacted. Unless federal agencies such as the CIA and the FBI satisfactorily explain their reasoning for withholding part or all of these lingering documents from the public, all records, according to a memorandum signed by President Joseph R. Biden on 22 October 2021, must be released no later than 15 December 2022.6

Stone interviews many people affiliated with ARRB in JFK Revisited who claim that the now-unclassified evidence largely supports his and Sklar’s suspicions, as dramatized in JFK, that Oswald was not the shooter (and may not even have been on the sixth floor of the Texas School Book Depository when the assassination occurred), but, if JFK Revisited has weaknesses, they are Stone’s refusal to interview people who dispute his analyses of this new research and his resistance to considering alternative explanations of the findings, which makes his documentary, for all its sober reflections upon Kennedy’s legacy and American history, a handmaiden to its better-known cinematic cousin that follows the outline of JFK’s narrative right down to tugging the viewer’s heartstrings by appealing to truth, justice, and American fortitude in terms identical to Jim Garrison’s concluding courtroom oration in Stone’s 1991 masterpiece.

And yes, JFK remains a masterpiece despite three major flaws that stand out in even-starker relief thirty years later.* The movie’s depiction of women, chiefly through the character of Liz Garrison but even through Laurie Metcalf’s Susie Cox (an assistant district attorney and dogged investigator in Garrison’s fictionalized office who didn’t exist in real life, but whom Metcalf plays with gusto) is so sexist that the film at times verges into misogyny.

JFK also makes a meal of Kennedy’s importance to the civil-rights struggle yet gives no seat at the table, and certainly no prominent voice, to any Black character (aside from a few stray comments uttered by Garrison’s housekeeper Mattie, played by Pat Pierre Perkins), or, other than several Cuban refugees who so despise Kennedy for not providing air cover during April 1961’s Bay of Pigs invasion that they rant against him in vulgar terms, no non-white characters at all.

Perhaps most objectionably, the film’s portrayal of its LGBTQ characters—Clay Shaw, David Ferrie, and a composite character named Willie O’Keefe (played, in a remarkable performance, by Kevin Bacon)—includes stereotypes about gay men so hoary that the proudly racist O’Keefe, while being questioned by Garrison during a scene shot on site at Louisiana’s notorious Angola state penitentiary, propositions Garrison sexually, says that “everybody likes to make themselves out to be something more than they are, especially in the homosexual underworld” and, later, in one of the most memorable lines of dialogue in a film packed with them, exclaims, “You a goddamn liberal, Mr. Garrison! You don’t know shit ‘cause you never been fucked in the ass!” As terrifically as Bacon delivers these lines, their comedy now strikes me as the unintended consequence of straight men trying and failing to write words that they imagine gay New Orleans hustlers speak aloud.

Stone cast straight actors to play JFK’s gay men, perhaps to avoid outing performers who remained in the closet in 1991, but these characters’ outrageousness made him uncomfortable enough to have Liz Garrison, during Clay Shaw’s trial, accuse her husband of prosecuting Shaw because he’s gay, a charge that Jim angrily denies.

Stone also denies that JFK includes negative gay stereotyping in his uncomfortable 7 April 1992 interview with The Advocate’s Jeff Yarbrough (titled “Heart of Stone” and available on Pages 508-17 of The Documented Screenplay), but Stone is whistling past the graveyard here, either responding elliptically or evading entirely Yarbrough’s observations about how JFK seems to code its gay characters as villains but cannot, in Stone’s view, be considered the least bit homophobic.

As distressing as Stone’s animadversions are, the party scenes of Ferrie and O’Keefe sniffing amyl nitrate while dressed as Napoleon Bonaparte and Marie Antoinette—with their faces painted alabaster white—and Shaw painted head to toe in gold while wearing the Greek god Hermes’s winged helmet—how Stone convinced Tommy Lee Jones to submit to this make-up regimen is anyone’s guess—come straight out of those evangelical “educational” films of the 1950s and 1960s warning parents against allowing their children to consort with “men of a certain disposition.”

And yet, despite these problems, JFK still strikes me as a masterwork, deeply flawed in the ways discussed above, but losing none of its power to grip, to compel, and to rouse in its American viewers deep reflections about their nation’s history, their governments’ responsibilities to the principles of truth and justice, and their own civic roles to play in upholding its democratic ideals. Thirty years on,* this movie remains a dizzyingly entertaining trip down, up, and down the rabbit holes of smart speculations, questionable rumors, and ridiculous delusions about Kennedy’s assassination, but, more broadly, about our lives as citizens of a country that strives—or should strive—to be a more perfect union even if attaining this goal seems farther away than it ever has.

How earnest, innocent, and nutty a conclusion is that to draw from a film so steeped in disappointment, darkness, and depravity? Perhaps this unforeseen response explains why, even after three decades of living with its implications, I can still say, with a mostly straight face, “all the way with JFK.”

NOTES

Roger Ebert, “Great Movies: Do the Right Thing,” 27 May 2001, RogerEbert.com, https://www.rogerebert.com/reviews/great-movie-do-the-right-thing-1989.

Martin Sheen, interviewed by James Lipton, Inside the Actors Studio, Season 9 Episode 6, 18 May 2003, 52 minutes. Sheen makes this comment about his sense of patriotism in response to an audience member’s question, but has offered similar remarks about his political activism many times over the years.

Sheen’s episode of Inside the Actors Studio is not widely available for digital streaming, although Ovation TV’s Ovation NOW service includes many prior episodes from this long-running series’s archives.

Publication information for both books follows: 1) Jim Garrison, On the Trail of the Assassins: My Investigation and Prosecution of the Murder of President Kennedy, Sheridan Square Press, 1988; and 2) Jim Marrs, Crossfire: The Plot That Killed Kennedy, Carroll and Graf, 1989.

Two other good sources to consult in this regard are Michael Kazin’s 2017 Journal of American History article “An Idol and Once a President: John F. Kennedy at 100” and Mark White’s 2013 History: The Journal of the Historical Association essay “Apparent Perfection: The Image of John F. Kennedy.” The scholarship about JFK’s presidency is so extensive that competing views of his time in office are plentiful (and inevitable).

Publication information for all six sources follows: 1) Seymour M. Hersh, The Dark Side of Camelot, Back Bay Books, 1997; 2) Maurice Isserman and Michael Kazin, America Divided: The Civil War of the 1960s, Oxford University Press, 2000; 3) Thomas G. Paterson (editor), Kennedy’s Quest for Victory: American Foreign Policy, 1961-1963, Oxford UP, 1989; 4) Garry Wills, The Kennedy Imprisonment: A Meditation on Power, Little, Brown and Company, 1982; 5) Michael Kazin, “An Idol and Once a President: John F. Kennedy at 100,” Journal of American History, vol. 104, no. 3, 2017, pp. 707-26; and 6) Mark White, “Apparent Perfection: The Image of John F. Kennedy,” History: The Journal of the Historical Association, vol. 98, no. 2, 2013, pp. 226-46.

David Ansen, “A Troublemaker for Our Times: Oliver Stone’s Heretical History Is a Stunner,” Newsweek, 22 December 1991, https://www.newsweek.com/troublemaker-our-times-201118.

Although Ansen’s review remains available on Newsweek’s website (see above), the byline now reads “Newsweek staff.” The original essay, correctly credited to Ansen, can be found on Pages 295-97 of Oliver Stone’s and Zachary Sklar’s published script, JFK: The Book of the Film: The Documented Screenplay (Applause Books, 1992).

“Memorandum for the Heads of Executive Departments and Agencies on the Temporary Certification Regarding Disclosure of Information in Certain Records Related to the Assassination of President John F. Kennedy,” signed by President Joseph R. Biden, Jr., 22 October 2021, https://www.whitehouse.gov/briefing-room/statements-releases/2021/10/22/memorandum-for-the-heads-of-executive-departments-and-agencies-on-the-temporary-certification-regarding-disclosure-of-information-in-certain-records-related-to-the-assassination-of-president-john-f-k/.