Blowhards, Best Buds, & Big Bads

“Revolution of the Daleks” rings in the new year as only Doctor Who can.

Doctor Who

“Revolution of the Daleks”

Series 12, Episode 11 / New Year’s Day Special 2021

Written by Chris Chibnall

Directed by Lee Haven Jones

Starring Jodie Whittaker, Tosin Cole, Mandip Gill, Bradley Walsh, and John Barrowman

Guest Starring Helen Anderson, Nathan Armarkwei-Laryea, Nicholas Briggs, Nathan Stewart-Jarrett, Harriet Walter, and Chris Noth

71 minutes

Original broadcast 1 January 2021

1. Hello, Doctor, My Old Friend

Although slightly less than an eternity, Doctor Who’s 2021 New Year’s Day Special, “Revolution of the Daleks,” came across our television screens exactly ten months after the program’s previous episode (the Series 12 finale, “The Timeless Children”) aired all the way back in March 2020. This interregnum, however, felt much longer considering that 1 March 2020 saw the beginning of pandemic lockdowns for many (if not most) of our planet’s inhabitants, meaning that time dilated so strangely in the intervening days and weeks that it seemed—I stress the word seemed—as if we all occupied a similar position to the Thirteenth Doctor (Jodie Whittaker) at the start of this latest adventure, to wit: We were imprisoned by overwhelming and unseen forces, repeating the same daily rituals in listless, even aimless, attempts to keep our spirits up despite the world’s best efforts to crush them.

The death reports chronicling COVID-19’s terrible toll on our fellow citizens were enough to make anyone morose. Joy was in short supply, laughter was intermittent, and optimism was a fool’s errand, at least during the pandemic’s early weeks, when failures of leadership across the globe—none more appalling than the Trump regime’s criminal dismissal of COVID-19’s lethality in favor of idiotic pronouncements about how the disease would simply disappear (the message being, “Get back to work and school like good little drones, you complainers, whiners, and plebes”)—made everything harder than it should’ve been.

I recall these events not to distress you, dear reader, by dredging up unhappy memories of what I now call the Asterisk Year (or the Lost Year) of 2020, but to remind you of how badly we needed hope—any hope: small or large, silly or somber, rough or smooth. Chris Chibnall and the British Broadcasting Corporation (BBC) knew this essential truth as well as anyone, so they obliged Doctor Who fans by releasing short stories chronicling the further escapades of various Who characters (written by Chibnall, by ex-showrunner Russell T. Davies, and by ex-showrunner Steven Moffat, among others); short videos that followed up various New Who storylines; and, thanks to Doctor Who Magazine contributor-extraordinaire Emily Cook, “tweetalongs” to various New Who episodes that saw Davies, Moffat, and other production personnel take to Twitter to share their memories of making some of the program’s most beloved installments.

Such compassion in the midst of tragedy perfectly summarizes Doctor Who’s founding principles. Offering balms for the bruised spirits of fans, followers, and admirers who, bravely trying to preserve any scrap of happiness in their lockdown lives, found the isolation and mounting death counts tougher and tougher to take was an act of beauty on Chibnall et al.’s parts that remains inspiring even now, three years later.

Despite criticisms of Chibnall’s captaining of the New Who ship since he assumed showrunner duties from Moffat in 2017, his compassion in marshaling the franchise’s workers—past and present—to help its audience get through the roughest of times was nothing short of magnificent. Neither Chibnall nor anyone else in Who world needed to do so given that they were enduring the same conditions, but the fact that Chibnall, the BBC, and so many people involved with Doctor Who took time to make us feel better during the Asterisk Year will remain, for me, an unforgettable kindness that saw them rise to the challenge of living, in real time, the values espoused by the program they produce.

“Revolution of the Daleks,” as such, occupies a unique position in the New Who firmament. This installment was, during its initial broadcast, not merely another episode, but the first outing since life went haywire, barmy, crazy, and insane. As the second entry in what we may now call Chibnall’s “Dalek Trilogy,” it picks up the narrative ball from “Resolution” (the 2019 New Year’s Day Special) and runs with it so capably that, if you watch them back-to-back, you’re in for one of the best New Who two-parters since the program returned to our screens in 2005.

As a piece of drama, it’s as busy as any installment of the Chibnall era, even busier considering that this entry 1) forwards the showrunner’s Timeless Child mythology in unexpected ways, 2) returns John Barrowman’s redoubtable Captain Jack Harkness to the Who flagship for his first full voyage in nearly 13 years, and 3) sees two of the Doctor’s three companions depart for good.

This piece’s emotional landscape, in other words, ranges over hill and dale, peak and valley, summit and nadir as only Doctor Who can. “Revolution of the Daleks,” in sum, isn’t as triumphant as it should be, yet this outing approaches a level of fineness that bodes well for Series 13 despite underscoring some of Chibnall’s most objectionable authorial tics and, as a result, falling just shy of its best holiday-themed predecessors.

2. Devils & Details

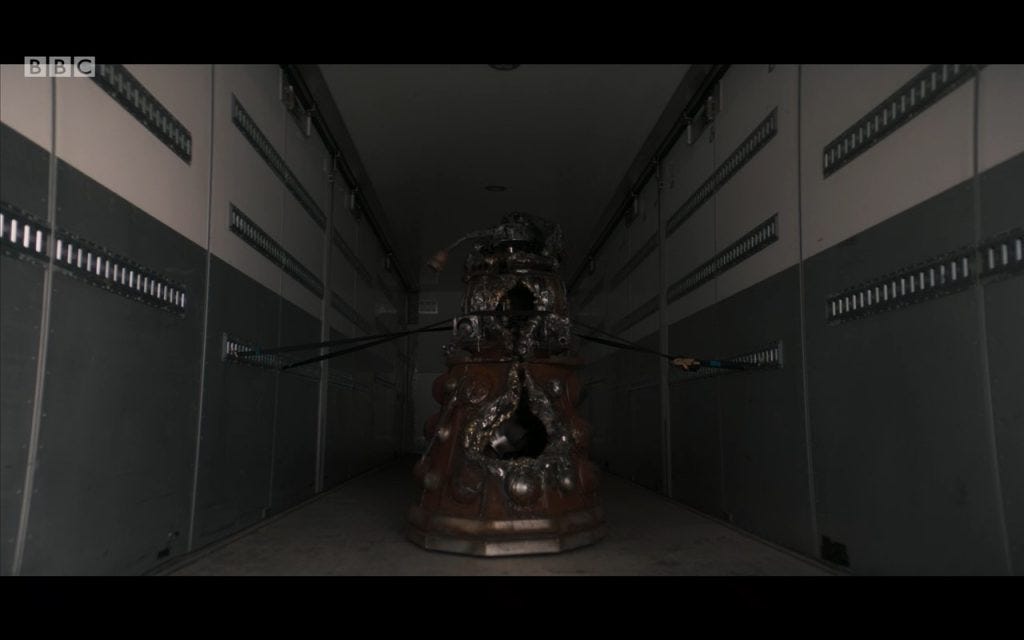

“Revolution of the Daleks” begins with a short recap of the major events in “Resolution,” especially Team TARDIS’s defeat of a Reconnaissance Dalek whose revival thousands of years after losing its battle with an army of 9th-Century warriors (fought on the land that becomes Sheffield, England) allows this mutant extraterrestrial to grow into intimidating proportions, to reconstruct its battle armor, to slaughter an entire squad of British troops, and to attack England’s General Communications Headquarters hoping to alert Daleks elsewhere in the universe that Earth is ripe for subjugation.

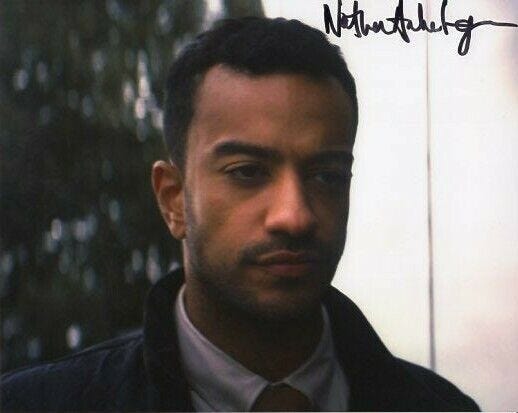

The 2021 New Year’s Day Special proper begins 367 minutes later, when a driver named Armen (Nathan Armarkwei-Laryea) is assigned to transport this Reconnaissance Dalek’s destroyed carcass to Depository 23 in a large, anonymous truck (or lorry, as the Brits might say). Armen unwisely buys hot tea from a roadside stand whose sole worker poisons his drink and steals the Dalek from him (on behalf of an unknown organization).

How this group’s leaders knew that Armen would stop at this particular coffee stand, thereby giving them the opportunity to purloin the remains of an extraterrestrial invader whose identity has certainly been kept secret from the general public, is either an enormous coincidence crafted by Chibnall to get the plot rolling or, alternatively, evidence of an intelligence operation so sophisticated that its designers know: 1) that the Reconnaissance Dalek exists at all, 2) when and how this Dalek’s remains will travel to a government holding facility, and 3) enough about Armen’s personal habits—to say nothing of his identity—that a single female operative can temporarily take over a highway refreshment kiosk long enough to poison his drink (or, instead, set up this small trailer as the first step in commandeering Armen’s truck).

These scenes illustrate, in less than five minutes, Chibnall’s concurrent strengths and weaknesses as a writer. He quickly establishes, through a few lines of dialogue shared with Armen’s apparent supervisor, Rachel (Helen Anderson), that Armen’s mother is ill and, through snapshots of Armen’s mum taped to the truck’s dashboard, that Armen deeply loves her.

The deftness by which Chibnall gives Armen a backstory full of challenges and responsibilities is laudable insofar as it tells us that Armen has held his job long enough to share personal details with his colleagues and that driving top-secret remains to government labs has become routine. This sense of a larger world existing independently from New Who’s protagonists extends Davies’s and Moffat’s (but especially Davies’s) commitment to grounding Who in quotidian details that anchor the franchise’s fantastical elements in working-class social realities (even if social realism is hardly the first genre that leaps to mind when thinking of Doctor Who).

Armen’s unsung work, in simpler parlance, spotlights minutiae that Doctor Who normally glosses over—or outright ignores—in its rush to tell big stories at breakneck speed. For anyone who’s ever wondered about the drudgery involved in cleaning up the Doctor’s messes, “Revolution of the Daleks” peeks behind this curtain in ways we haven’t seen since Torchwood (2006-2011) went off the air in 2011. Chibnall, lest we forget, was this spinoff’s showrunner during its first two seasons, so his choice to include Armen makes sense from a ground-level perspective.

Bringing life and personality to such a minor character also speaks well of Chibnall’s commitment to nuance, yet this sequence’s expedience lands so firmly on the side of convenience that its dramatic soundness is questionable. Why show this character and these events at all if they depend upon every action taken by every participant slotting into pace so perfectly that any deviation—a flat tire, a traffic jam, a bathroom break—would derail the entire plan?

The answer may be that Chibnall understands how much Doctor Who has relied upon coincidence since broadcasting its first episode on 23 November 1963, so he needn’t take seriously, much less earnestly, these moments’ believability. “Fair enough,” we might reply, even if saying so emphasizes how unlikely some details in “Revolution of the Daleks” are, or even if we say—as I do—that their improbability is a strength, not a weakness, of Chibnall’s approach to New Who’s storytelling.

“The details only matter when they matter,” we might claim, but this bit of circular reasoning concedes one fundamental truth of being a Doctor Who fan: You either enjoy a fair share of nonsense—happy, funny, whimsical poppycock free from the suffocating shackles of realism (however you define that term)—or you don’t remain a Whovian for long.

3. Jack Attack

“Revolution of the Daleks” is no more or less absurd than any other New Who installment broadcast since “Rose” launched the series in March 2005, but its special place in New Who’s lineup—coming one year into pandemic lockdowns that its cast and crew couldn’t predict—draws attention to the franchise’s unique blend of caprice, constancy, fantasy, and fact. If these elements seem paradoxical, all the better, for this episode gets going by stopping in place. Only by examining the consequences of the events dramatized in its immediate predecessor, “The Timeless Children,” does “Revolution of the Daleks” engage our full attention.

We find the Thirteenth Doctor already adjusted to life in the Judoon prison to which she was confined at that entry’s conclusion. The sight of the Doctor enduring an ingrained daily routine of greeting her fellow prisoners—including an Ood, a Pting, a Silence, a Skithra, a Sycorax, and even a Weeping Angel (whom the Doctor calls “Angela”)—and the humdrum normalcy of scratching hashes into her cell’s walls (to mark another day’s passing) are, to say the least, bothersome. The thousand-plus hashes covering every available surface suggest the disquieting possibility that the Doctor’s been captive for years without attempting escape.

The haunted expression on her face and in her eyes reveals a woman so deep in thought that mulling the extraordinary information the Master (Sacha Dhawan) disclosed (about the Doctor’s status as the Timeless Child) has so profoundly unsettled the Doctor that the she’s lost her zest for life.

That the Doctor may have experienced numerous incarnations before becoming the First Doctor (William Hartnell in Classic Who and David Bradley in New Who) would be enough to set anyone off kilter, but Chibnall here explores unusual emotional territory for his protagonist by having her become the passive recipient of Judoon justice rather than impatiently trying to reclaim her freedom. Whittaker’s terrific performance helps transform this uncharacteristic dolefulness into a natural response, while Segun Akinola’s plaintive music and Jake Skinner’s sober editing help sell this change to viewers unaccustomed to seeing the Doctor resigned to unfortunate circumstances for more than a few minutes.

The Doctor’s three companions—Ryan Sinclair (Tosin Cole), Yasmin “Yaz” Khan (Mandip Gill), and Graham O’Brien (Bradley Walsh)—have moved on with their lives in Sheffield, England, or, at least, Ryan and Graham have. They visit Yaz in the spare TARDIS that the Doctor salvaged from Gallifrey at the conclusion of “The Timeless Children” (the same TARDIS she managed to return to 2020 Sheffield to protect her friends from Gallifrey’s destruction). This timeship’s exterior resembles a normal, middle-class house, while its interior has become Yaz’s living quarters as she struggles to locate the Doctor. Yaz, indeed, angrily refuses to countenance Ryan’s and Graham’s suggestion that the Doctor may have perished while battling the Master.

Mandip Gill thickens Yaz’s Yorkshire accent to demonstrate just how isolated and obsessive her character has become. The companions’ dissension keys into small clues that Chibnall and his writing staff weave throughout Series 12, beginning with Ryan’s doubts about continuing to travel with the Doctor (as seen in the two-part “Spyfall” premiere; the seventh entry, “Can You Hear Me?”; and “The Timeless Children”) and culminating in Graham’s heartfelt “Timeless Children” chat with Yaz, where he tells her that she’s the best person he’s ever met, one who’s “never afraid and . . . never beaten. . . . You’re doing your family proud, Yaz, you really are. In fact, you’re doing the whole human race proud.”

Yes, sir, and yes indeed, which makes the tension among Yaz, Ryan, and Graham in “Revolution of the Daleks” even more palpable. Their interaction’s emotional maturity and good acting are commendable, as is Yaz’s immediate desire to jump into action when Ryan shows her leaked, year-old video footage of Daleks participating in a riot-control exercise supervised by Jack Robertson (Chris Noth), the blowhard financier Team TARDIS encountered in Series 11’s fourth installment, “Arachnids in the UK.”

Robertson, we realize, stole the Reconnaissance Dalek shell from the British authorities and handed it to Leo Rugazzi (Nathan Stewart-Jarrett), the CEO and founding genius of Rugazzi Technologies, an advanced-hardware corporation that Robertson purchased with the express purpose of developing artificially intelligent security drones (based on the Reconnaissance Dalek’s design) to sell to governments and businesses around the world.

Robertson finds a willing partner in Jo Patterson (Harriet Walter), the British cabinet’s newly appointed Technology Secretary, who agrees to purchase Dalek drones—fully automated and controlled by AI programming that Leo’s developed—when, in “a year, give or take,” Robertson can complete building an army of them. This day arrives to find Patterson having ascended to her party’s top leadership role, making her the new British Prime Minister. Ryan, Yaz, and Graham confront Robertson about his double dealing, but the man’s bodyguards chase them away, which stiffens their resolve to stop Patterson’s and Robertson’s scheme from succeeding despite the Doctor’s absence.

Robertson, however, isn’t the only Jack who returns in “Revolution of the Daleks.” While hailing her fellow inmates during another daily walk around the exercise yard, the Doctor is amazed to hear Captain Jack Harkness (John Barrowman) call to her. Seen for less than five minutes in “Fugitive of the Judoon,” the pivotal Series 12 episode that shifted the Timeless Child mythos into overdrive by unveiling the previously unknown Fugitive Doctor (Jo Martin) to New Who’s audience, Captain Jack makes a more jubilant return here than he did there.

Chris Chibnall (remember, showrunner of the Harkness-led spinoff Torchwood’s first two seasons) has written more onscreen material for Captain Jack than anyone else, even Russell T. Davies, who created the character in collaboration with Steven Moffat, who authored Jack’s inaugural New Who appearances in Season 1’s bravura two-parter “The Empty Child” / “The Doctor Dances.” Jack Harkness is a franchise favorite—perhaps the franchise favorite par excellence (second only the Doctor herself / himself)—due to the good writing of this character’s tenure on both programs and to Barrowman’s exuberant performance of the role.

And, just like his “Fugitive of the Judoon” appearance, Barrowman’s frothing and fizzing presence in “Revolution of the Daleks” is so welcome that I hope Davies finds ways to return both Captain Jack and Torchwood to television now that Davies has resumed the reins as New Who’s showrunner for 2023’s Sixtieth Anniversary Special (and seasons beyond). Granted, this task is nearly impossible given the allegations about Barrowman’s objectionable behavior on the sets of Doctor Who and Torchwood that dogged the actor throughout 2021, for which he’s issued half-hearted apologies, so I won’t hold my breath.1

Chibnall and Barrowman, however, were clearly thrilled to bring Captain Jack back to the flagship program for 71 minutes, so they make the most of every opportunity. The prison break that Jack masterminds—using a device he dubs “a breakout ball” (short for “temporal-freezing gateway-disinhibitor bubble”) and a carefully hidden vortex manipulator (his favorite escape mechanism, a wristband that permits instant space-and-time teleportation)—isn’t simply a scream, but an unmitigated joy to watch.

Chibnall even includes a marvelous callback to Series 1’s penultimate episode, “Bad Wolf,” that sees Jack reply, when the Thirteenth Doctor asks how he managed to smuggle the vortex manipulator into their Judoon prison, “You really want me to answer that?”2 The instant recognition and slight disgust that cross the Doctor’s face are so terrific (kudos, Jodie Whittaker!) that I burst out loud laughing, making me grateful, for once, that I wasn’t sipping coffee, tea, beer, or wine while watching.

This fun doesn’t last long, for when the Doctor and Jack take her TARDIS to Graham’s Sheffield living room, Yaz’s angry reaction—she shouts “We were worried about you!” and shoves the Doctor hard after the latter, chirpy as always, walks out the TARDIS’s front door to declare, “I was in space jail!”—surprises the Doctor, who appears momentarily poleaxed when Ryan reveals that she’s been away ten months.

As Graham comments, “your time machine ain’t the best at running to time, is it, though?” to underline how abandoned the three companions feel. Captain Jack tells the Doctor, during their prison break, that it took him 19 years to work his way into the cell next to hers, meaning that the Doctor spent at least two decades moping about space jail getting her head together. A further implication suggests that, in their original timeline, Ryan, Yaz, and Graham went that long without hearing from the Doctor, who may have changed history by re-entering their lives on New Year’s Day 2021, but whose extended absence offers good story fodder for ancillary New Who novels, short stories, and audio dramas.

These strong feelings play into the theme of fractured families that New Who has explored since Series 1—and that’s fascinated Chibnall during his residence as showrunner—to pave the way for Ryan and Graham to exit the TARDIS as “Revolution of the Daleks” ends. Yet before these departures occur, the Doctor’s reunited family must pursue one last adventure: defeating the reborn Reconnaissance Daleks (yes, plural) that menace Great Britain on New Year’s Day.

4. Farewell, Fam

After the complex storyline of “The Timeless Children,” the relatively straightforward plot of “Revolution of the Daleks” may be Chibnall’s attempt to slacken the narrative pace after tying the Doctor’s personal history into knots during the Series 12 finale. This entry’s premise demonstrates the dangers of melding unfettered disaster capitalism with overweening political ambition, with Jack Robertson hoping to earn additional millions after Prime Minister Patterson unwisely inaugurates what she calls “the Age of Security” by placing solar-powered Dalek “defence drones” (as they’re called) into every aspect of British life, including airports, police stations, government offices, border crossings, and even the Tower of London.

Patterson introduces these sinister mechanisms to her constituents in perhaps the most ill-advised press conference ever seen in New Who. Standing outside 10 Downing Street, the Prime Minister speaks platitudes about the British public embracing forward-thinking solutions to difficult problems (Chibnall, ever the optimist, floats notions like this one with a mostly straight face) before the Daleks, inevitably and remorselessly, begin massacring everyone in sight, including Patterson, whose time in office is the shortest political career in New Who history.

How, we must ask, do the Daleks continue turning the tables on supposedly sophisticated, yet stubbornly gullible people like Patterson and Robertson who, given the many Dalek attacks against Earth since Series 1’s 2005-2006 timeframe (and the umpteen subsequent extraterrestrial invasions), really should know better? Chibnall may indeed be criticizing humanity’s deplorably short historical memory, a supposition that gains credence considering that Leo Rugazzi, a prodigy, has apparently forgotten the same events.

Leo goes several steps further by harvesting the Reconnaissance Dalek’s organic remnants from its blasted shell, growing these cells into a new Dalek mutant, and hooking this creature into the central mainframe of Robertson’s business empire. This revived Dalek gains access to every resource (financial and otherwise) at Robertson’s command, permitting the creature to build a Dalek clone farm in Osaka, Japan that breeds enough mutants to fill the thousands of Dalek defence-drone casings that Robertson’s construction firms 3D-print to the Daleks’ original, battle-ready specifications. Leo’s mutant captures and controls him like a puppet master manipulating a marionette—in the same frightening manner that the Reconnaissance Dalek exploits the character Lin (Charlotte Ritchie) in “Resolution”—by climbing onto Leo’s back and using its telepathic abilities to overrule his mind.

The Doctor, Graham, and Ryan eventually abduct Robertson from his British headquarters, then venture, via the TARDIS, to Osaka to stop this new Dalek scheme. Yaz and Captain Jack are already there, conducting reconnaissance during a scouting trip that includes my two favorite scenes in “Revolution of the Daleks.” The first is a sincere conversation between the immortal, worldly wise, but not world-weary Jack and the emotionally vulnerable Yaz, who confesses to wishing she’d never met the Thirteenth Doctor because “it felt cruel. To be shown something I couldn’t have any more. Felt like, um, I’d rather not have known. I’d rather not have met her, ‘cause having met her and then . . . being without her, well, that’s worse.”

Mandip Gill is marvelous here, while John Barrowman keeps pace when Jack cites his own history with the Doctor to urge Yaz to enjoy her TARDIS time (since so few people receive this privilege). Chibnall writes lovely words for Gill and Barrowman to say, while director Lee Haven Jones rests the camera on their faces, eschewing flamboyant movements and flashy editing tricks, to permit this quiet discussion to build in power until Jack wipes away a single tear from Yaz’s right cheek. This action confirms what careful viewers have suspected since Series 12’s middle episodes, if not Series 11’s final outings: Yaz’s affection for the Thirteenth Doctor has grown into love similar to Martha Jones’s (Freema Agyeman’s) unrequited passion for the Tenth Doctor (David Tennant) during Series 3.

Chibnall follows this conversation with the episode’s most horrifying sequence, set inside the Dalek clone farm, whose sickening green light obscures two Dalek mutants escaping their tanks. The first mutant jumps onto Jack’s head in an unmistakable allusion to the Alien franchise’s facehuggers, while the second leaps onto Yaz’s back, who frees Jack from his attacker only to find herself in danger of being manipulated like Leo. Jack thankfully vaporizes both mutants with his square sonic blaster (another Series 1 callback), but neither he nor Yaz (nor the rest of Team TARDIS, once they land in Osaka) can annihilate the remaining, countless clones before Leo’s Dalek teleports them all into Robertson’s defence-drone husks.

The Doctor’s solution to this quandary is elegant and, indeed, among the cleverest bits of poetic justice any incarnation has foisted upon these giant pepperpots. Chibnall employs every element at his disposal, from the spare TARDIS that spent ten months masquerading as a house in Sheffield to the Doctor’s longtime talent at pulling “the old switcheroo” on creatures so bloodthirsty that, in their rush to destroy the Doctor, they ignore obvious red flags. And special mention must be made of Nicholas Briggs’s superb acting. He voices the Daleks, especially the mutant controlling Leo, so menacingly that Briggs—one of the few cast members who’s been with New Who since Series 1—has become a franchise treasure.

This dazzling sequence would normally conclude the New Year’s Day Special on high notes that leave us satisfied, if not gorged, on the holiday goodness Chibnall’s concocted, but clock-watchers know that nearly ten minutes must elapse before “Revolution of the Daleks” concludes. The reason, we soon learn, involves Ryan telling the Doctor, Yaz, and Graham that he’s decided to stay in Sheffield, which will include him continuing to protect Earth from strange phenomena.

Or, as Ryan poignantly tells the Doctor, “Look, Doctor, before I met you, I didn’t know what I wanted to do with me life. And . . . and now—and now I know.” This decision prompts Graham to stay behind and the Doctor to give both men their own psychic paper to facilitate their vow to save the planet from extraterrestrial threats. She regrets having “missed my time with you” during her ten-month imprisonment, but doesn’t hector, bully, or beseech Ryan and Graham to stay.

This intricate welter of emotions—joy, sadness, camaraderie, and regret—occasions one of New Who’s best farewell scenes as Team TARDIS enjoys its final group hug, shot from below with all four faces forming a circle that not only fills the screen but also lets us study each character’s visage. Whittaker, Cole, Gill, and Walsh conduct a masterclass in screen acting here, for no matter how high their feelings run, their restraint is exactly how people who deeply love one another behave when they wish to avoid breaking down into sobs. And, if “Revolution of the Daleks” had ended here, it would be an emotionally perfect sendoff for Tosin Cole and Bradley Walsh, who’ve been aces since their introduction in Series 11.

5. The Colors of Change

Chibnall, however, gives Ryan and Graham a brief epilogue to bring their story full circle. Ryan, who lives with dyspraxia, attempts to ride a bicycle through the same Sheffield moor where we first met Grace Sinclair-O’Brien (Graham’s wife and Ryan’s grandmother, wonderfully played by Sharon D. Clarke) in the Thirteenth Doctor’s inaugural adventure, “The Woman Who Fell to Earth.” Ryan falls but rises undaunted, just as he did in the Series 11 premiere, citing many of Team TARDIS’s adventures through space and time as reasons never to surrender to failure. Then, in a moment designed by Chibnall to rip heartstrings from our chests, both men see a momentary vision of Grace standing in a beam of sunlight and smiling at them.

My eyes welled at this sight, just as Chibnall intended, but I couldn’t enjoy the resulting emotions as effusively as Chibnall wanted because seeing Grace again, voiceless in death, reminded me of how much material Doctor Who’s viewers missed due to Chibnall’s choice to kill Grace in “The Woman Who Fell to Earth” (rather than make her a full-time companion). My review of Series 11’s premiere episode more fully explains my regrets about this misguided decision, but our final glimpse of Grace highlights another weakness of Chibnall’s writing in “Revolution of the Daleks” specifically and his era of New Who generally: the frequency with which Chibnall creates characters of color only to shuffle them off this mortal coil.

Consider, for instance, that the two people most responsible for the Dalek invasion—Armen and Leo Rugazzi—are Black men serving white bosses who cast them off without concern for their lives. Robertson, indeed, upbraids Leo for going beyond his brief in salvaging and cloning the Reconnaissance Dalek’s organic remnants despite relying upon Leo’s genius to make the Dalek defence-drone program into the largest commercial venture Robertson’s ever undertaken (and despite Leo’s intense curiosity being key to his success as a scientist and as a tech innovator). Robertson denies responsibility for the Dalek invasion by claiming to have lured the Daleks into a trap when, in fact, his cowardice leads him to sell out humanity. Robertson lies when he says, “I was deliberately acting as a decoy” because he allies himself with whomever seems most powerful at the moment: first the Daleks, then the Doctor.

Graham can’t believe how media outlets celebrate Robertson after this crisis has passed, but Ryan isn’t surprised at all. These diverging responses are Chibnall’s keenest comments about how white privilege insulates its beneficiaries from blame by dismissing the accomplishments and damaging the reputations of people of color. Even so, the Doctor doesn’t challenge Robertson’s self-serving falsehoods, while even Captain Jack—who says “I still say we should leave him here” when he, Ryan, and Graham encounter Robertson negotiating with the Daleks aboard their mothership (the same vessel they’re about to destroy with explosive charges)—lets Robertson get away with his crimes.

Life isn’t fair, we might observe, before going about our merry ways. Robertson, moreover, so clearly represents Donald Trump in “Revolution of the Daleks,” just as he does in “Arachnids in the UK,” that we might praise Chibnall for dramatizing a dispiriting truth about humanity’s wayward ways: The worst people in the world often profit from their cowardice and their criminal behavior.

Perhaps . . . yes, perhaps . . . but I’m not inclined to give Chibnall the benefit of the doubt here. Including a vision of Grace in this installment’s final moments doesn’t bring formal closure to Ryan’s and Graham’s time on Doctor Who, bookending each man’s experience by concluding their stories where they began, so much as it underscores how crucially “Revolution of the Daleks” depends upon sacrificing Black characters to complete its narrative.

Emmet Asher-Perrin, in their smart 2018 Reactor Magazine review of “The Woman Who Fell to Earth” (titled “Because We’re Friends Now”), so aptly analyzes the implications of killing Grace during her first New Who outing that we can see how Chibnall’s commitment to diversity, although largely positive (Chibnall is, after all, the man who cast the first female Doctor, who cast the first Black woman as the Doctor, and who paired two companions of color for the first time in franchise history), isn’t always as thoughtful as it should be:

Knowing, as fans generally do, that she wasn’t set to be one of the main companions for the season, I was worried that Grace might die when we met her at the start of the episode. But then I thought, no, they couldn’t do that. On the very first episode showcasing a female Doctor, they wouldn’t kill another woman, an older woman, a woman of color, just as we were coming back into the fold. An incredible woman in her own right, a woman who makes it clear that she should be the companion, they wouldn’t do that to her or to us.3

These words, as true now as they were then, are equally accurate in light of Chibnall’s decision to kill Armen and Leo in “Revolution of the Daleks.” Asher-Perrin’s comments about Grace’s death in “The Woman Who Fell to Earth” also illustrate that the showrunner didn’t learn his lesson before writing Ryan and Graham out of “Revolution of the Daleks,” either. “I miss everything that she deserved to experience and all the adventures she’ll never get to have,” Asher-Perrin says in a particularly cogent passage, observing that “perhaps something miraculous will happen—Doctor Who is known for its share of revivals and reunions—but I’m not giving them any points until I see it.”4

No points are deserved despite Chibnall returning Grace to New Who in four additional Series 11 and 12 episodes (respectively, “Arachnids in the UK,” “It Takes You Away,” “Can You Hear Me?,” and her brief “Revolution of the Daleks” cameo). Grace’s final appearance instead raises issues Chibnall might prefer we simply forget.

Nicole Hill elaborates this theme in her excellent 2020 Den of Geek article “Doctor Who and the Complications of Color-Blind Casting” by writing, about Series 12’s “Spyfall” premiere, “From casting more diversely without thinking about how those diverse identities affect the character and story to killing off characters with marginalized identity in the service of white male character development, Doctor Who is making a lot of the same missteps that we see throughout the current era of storytelling.”5

Hill’s analysis loses no luster given how Chibnall concludes Grace’s, Ryan’s, and Graham’s character arcs in “Revolution of the Daleks,” which strikes a sour note (or two or three) in this otherwise affable review of New Who’s 2021 New Year’s Day Special. Yet conceding these weaknesses helps us better understand the good and the bad, the positive and the negative, the feats and the failures of Chibnall’s generally fine work in Series 12.

My misgivings, in other words, cannot (and should not) obscure the high points of “Revolution of the Daleks,” but this installment isn’t just a fun romp through the time vortex or a nice capper to Series 12’s many successes despite having panache to spare. Chibnall, his writers, his cast, and his production crew have worked too hard to make Doctor Who thoughtful entertainment—delirious, joyful, sometimes unhinged entertainment that keeps me coming back for more—to ignore flaws sometimes buried so deeply inside the stories Chibnall and company choose to tell that they might hope we minimize or ignore them.

So yes, dear reader, I recommend “Revolution of the Daleks” to you as I’ve recommended every Chibnall-era episode of New Who in my appraisals of Series 11, Series 12, and Series 13. This one’s worth watching, pondering, discussing, watching again, mulling over, arguing about, and—best of all—enjoying as an entry that will engage your heart and your mind.

Chris Chibnall, Jodie Whittaker, Tosin Cole, Mandip Gill, Bradley Walsh, and every other member of New Who’s exceptional crew have my admiration and my gratitude. “Revolution of the Daleks” isn’t perfect, but, then again, we wouldn’t want it to be, would we? How terrible would we feel if there was nothing to discuss, only praise to heap? Chibnall and his creative partners have given us enough to relish for days, weeks, and years on end, so I sign off these Series 12 reviews by offering felicitations for a job mostly well done and, as always, cheerfully received.

Thank you, one and all.

FILES

NOTES

Barrowman, according to numerous May 2021 media reports, was accused of exposing himself on the sets of Doctor Who and Torchwood, with then-executive producer Julie Gardner confirming to Out Magazine on 7 May 2021 that she officially reprimanded Barrowman for his Torchwood behavior when complaints from production personnel reached her office. Barrowman later apologized for “tomfoolery” and “larking about,” but denied sexually harassing anyone.

These allegations came to light after actor Noel Clarke, who played Mickey Smith in Doctor Who Series 1 through 4, faced multiple accusations of bullying, verbal abuse, and sexual harassment in a 29 April 2021 Guardian exposé that Clarke vehemently denied. Interested readers should find Princess Weekes’s 10 May 2021 The Mary Sue article “Doctor Who Actor John Barrowman Apologizes for Repeatedly Exposing Himself on Set” a useful starting point for information about the accusations against Barrowman and Clarke.

For the uninitiated, “Bad Wolf” (set in the year 200,100) finds Captain Jack participating in a roboticized version of the 2001-2007 reality show What Not to Wear, where, in front of millions of viewers, he’s stripped naked by the makeover androids Trin-E (voiced by real-life WNTW host/presenter Trinny Woodall) and Zu-Zana (voiced by real-life WNTW host/presenter Susannah Constantine). These droids then decide that Jack’s entire body requires making over, so they threaten him with a face-off (i.e., they try to behead him with a chainsaw, among other nasty cutting tools).

Jack saves his skin (literally) by producing a compact laser pistol from an unseen place behind him and then blowing apart each android’s head. The production crew shot footage of John Barrowman’s naked buttocks to confirm that Jack had stored this weapon in his rectum (in an apparent salute to “The Gold Watch,” the middle segment of Quentin Tarantino’s 1994 film Pulp Fiction), but the BBC’s Editorial Policy Department forced Davies and company to remove Jack’s nudity from this episode’s broadcast cut (“More’s the pity,” producer Phil Collinson jokes during this installment’s DVD and Blu-ray audio-commentary track).

Emmet Asher-Perrin, “Because We’re Friends Now: Doctor Who, ‘The Woman Who Fell to Earth,” 7 October 2018, Reactor Magazine, https://reactormag.com/because-were-friends-now-doctor-who-the-woman-who-fell-to-earth/.

Ibid.

Nicole Hill, “Doctor Who and the Complications of Color-Blind Casting,” Den of Geek, 17 January 2020, https://www.denofgeek.com/tv/doctor-who-the-complications-of-color-blind-casting/.