Star Trek: Picard

“Penance”

Season 2, Episode 2

Teleplay by Akiva Goldsman & Terry Matalas and Christopher Monfette

Story by Michael Chabon and Akiva Goldsman & Terry Matalas and Christopher Monfette

Directed by Doug Aarniokoski

Starring Patrick Stewart, Evan Evagora, Michelle Hurd, Alison Pill, Jeri Ryan, and Santiago Cabrera

Guest Starring Jon Jon Briones, Patton Oswalt, and Annie Wersching

Special Guest Star John de Lancie

54 minutes

Original broadcast 10 March 2022

1. Good to Bad

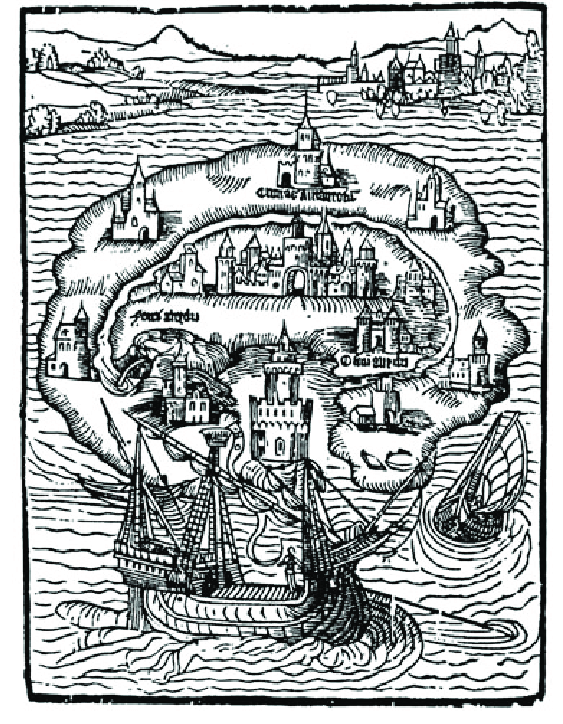

Whenever Star Trek aficionados mention the franchise’s utopian strivings, this conversation grows ripe with the possibility of misunderstanding. Far too many observers employ the term utopia to mean a perfect society (or, perhaps more accurately, a society without flaw) when, in truth, the word utopia was coined by Sir Thomas More as the title of his 1516 book (which may or may not be classified as a novel depending upon your historical perspectives, proclivities, and priorities) to describe this work’s social, political, economic, and even religious satire.

More wrote his Utopia in Latin (bearing the full title Libellus vere aureus, nec minus salutaris quam festivus, de optimo reipublicae statu deque nova insula Utopia), which, when finally translated into English in the year 1551, left literalists with something like A truly golden little book, not less beneficial than enjoyable, of a republic’s best state and of the new island Utopia, although English editions thankfully bore sleeker titles (i.e., About the Best State of a Commonwealth and the New Island of Utopia or Concerning the Highest State of a Republic and the New Island of Utopia).

So, without much prompting, you can understand why, for simplicity’s sake, More’s masterpiece has been called Utopia ever since. Resorting to simplicity, however, hazards misapprehending the meanings encoded in More’s book-length description of Utopia’s thoroughly imagined fictional society. Indeed, the notion that More’s island community has attained perfection for its members, who themselves exist in a prelapsarian state of bliss, is inaccurate for many reasons.

Utopia’s residents, it’s true, have their basic needs met by communities that include no more than 6,000 households per village, that organize themselves into 30-household districts each electing its own representative, that allow no private property to be purchased or sold, that tightly control each person’s life to ensure the domestic tranquility More emphasizes on page after page, and that award two slaves (criminals, conquered enemies, and other undesirables) to every family.

This last feature may hold little controversy for More and his patrician readers, but we can see how describing Utopia as perfect falls flat for 21st-Century audiences. More himself created the term utopia from the Greek roots ou (no) and topos (place)—so, no place (or nowhere)—to give his imaginary island a distinctive designation, even if scholars have noted almost since the day of the book’s publication that this title exactly matches, when pronounced in English, the term eutopia, which derives from the Greek roots eu (good) and topos—so, good place. The formulation of utopia as a perfect place—or, essentially, as close to a state of grace as humanity can achieve in the material world—occurs when readers conflate these two meanings, making utopianism a concept rife with contradictions, complexities, and contestations that create a fascinating genre unto itself (whether on the page, the stage, or the screen).

Star Trek, it goes without saying (yet I shall say it anyway), is a significant 20th- and 21st-Century example of utopian fiction, particularly when we understand that Trek’s imaginary future society isn’t perfect—meaning static or unchanging or unblemished—no matter how many times fans invoke Gene Roddenberry’s “vision” during recondite debates that cause the eyes of even Trek’s most passionate viewers (count me among them) to glaze when these arguments descend into shouting matches.

As anyone even passingly familiar with the production of The Original Series’s first season knows, Roddenberry and his extraordinarily talented creative team were making it up as they went along. True as this statement may be for every television series (or, really, for every creative enterprise in any medium), Roddenberry and his staff labored tirelessly to convince their audience that the 23rd Century was a real place populated by real people venturing into deep space to explore strange new worlds, to seek out new life and new civilizations, and, yes, to boldly go where no one had gone before.

This task proved so daunting that, according to Herbert F. Solow’s & Robert H. Justman’s 1996 book Inside “Star Trek”: The Real Story, Marc Cushman’s 2013 doorstop These Are the Voyages: TOS Season One, and Mark A. Altman’s & Edward Gross’s 2016 tome The Fifty-Year Mission: The First 25 Years (The Complete, Uncensored, Unauthorized Oral History of “Star Trek”),1 more than one person working behind the scenes on The Original Series (1966-1969), including Roddenberry himself, at some point checked themselves into the hospital to recuperate from exhaustion, if not other factors (such as alcoholism), so punishing were the hours required to get Star Trek up and running that first year.

These realities mean that Roddenberry’s vision, no matter how grand it seems in retrospect, was in those days simple: meet each week’s airdate without going so far over budget that NBC cancelled the series and put everybody out of work. Perhaps the most fun and fascinating facet of watching The Original Series’s first 15 episodes (including its rejected pilot episode, “The Cage”) is seeing Star Trek in the process of creating itself, developing the world—nay, the cosmos—of Starfleet, the Federation, and future humanity as each installment unfolds.

These earliest Treks test drive characterizations, technologies, themes, set pieces, and philosophical ideas without worrying too much about ambiguities or inconsistencies. The punishing pace of production, after all, demanded a new episode every week, forcing Roddenberry and his writers, producers, and technicians to revise—often on the fly—most aspects of Star Trek’s forward-thinking society due to the pressure-cooker environment that 1960s American network television imposed upon them. As such, Trek’s creators gradually settled into a view of humanity’s future that, while positive and certainly preferable to the fractious world they inhabited, is neither perfect nor perfectly peaceful.

2. Bad to Worse

No, the notion of human perfectibility in Star Trek took root during Roddenberry’s wandering-in-the-Hollywood-wilderness phase of the 1970s when, after serving as executive producer and creative consultant on the animated Star Trek series that ran for two seasons (from 1973 to 1974), he hit the college-and-convention lecture circuit with the enthusiastic, self-promotional talents of a latter-day P.T. Barnum.

Roddenberry refined these ideas while putting together several failed television pilots that never became weekly series (1973’s Genesis II, 1974’s Planet Earth, and 1974’s The Questor Tapes are only three), as well as Star Trek: Phase II, the aborted television series that was intended to launch a new Paramount television network to compete with ABC, CBS, and NBC; that would have chronicled the U.S.S. Enterprise’s (NCC-1701) second five-year mission under the command of James T. Kirk (William Shatner); and that eventually became the first Trek feature film (1979’s magisterial Star Trek: The Motion Picture).

By the time Roddenberry turned his attention to creating Star Trek: The Next Generation (1987-1994), he decided to portray future humanity—or, at least, the crew of the U.S.S. Enterprise-D—as overcoming the petty conflicts, rivalries, and jealousies so evident to anyone who lived through the 1980s, which immediately distinguished The Next Generation (TNG) from every other example of mass-media science fiction at the time. TNG’s first season is a remarkable display case for this approach to extrapolating humanity’s future. Yet, in an ironic development for many viewers who now vociferously invoke Roddenberry’s “vision” to claim that the New Trek productions launched in 2017 (with Star Trek: Discovery’s premiere) violate his founding principles, Trek’s wider fanbase generally considers this inaugural TNG season to be the show’s worst.

Yes, friends, even some defenders of “Gene’s vision,” as they call it, regard TNG’s first season as a dramatically limp excursion into the 24th Century that saw Roddenberry (or his lawyer, Leonard Maizlish) revise almost every script for its 26 episodes to the point that several writers left the program, either by choice or by being fired, including Dorothy “D.C.” Fontana, the woman whose contributions to onscreen Trek nearly rival Roddenberry’s and who parted company with The Next Generation after writing the early drafts of its pilot episode (“Encounter at Farpoint”), after serving as associate producer of its first 15 episodes, and after reworking Michael Michaelian’s script for that year’s 15th voyage, “Too Short a Season.”

Those people who’ve obsessively followed the Trek franchise’s behind-the-scenes development for decades (count me among them)—or just people who’ve seen William Shatner’s entertaining 2014 documentary Chaos on the Bridge—know that the first two years of The Next Generation’s production were so fraught with tension that TNG, at least behind the camera, was as far from utopian as it’s possible to be. The fights, firings, power plays, shouting matches, and office politics that Shatner’s documentary examines created what we’d now call a toxic working environment for many TNG cast and crew members, a dispiriting truth that demonstrates the distance between Roddenberry’s stated utopian principles for Star Trek’s imagined future and their intermittent (if not fully lapsed) application in real life.

I’ve never agreed that TNG’s first season is terrible (or, in a paradoxical term employed by viewers who’ve seen every episode, unwatchable) despite this first year’s growing pains. Season 1, after all, includes some excellent episodes (“Where No One Has Gone Before,” “The Big Goodbye,” “Datalore,” “Coming of Age,” “Heart of Glory,” and “Conspiracy”) amidst its direst outings (the appropriately reviled “Code of Honor,” for instance, is my choice as The Next Generation’s worst installment, if not the franchise’s worst-ever episode).

TNG Season 1, moreover, includes approaches, ideas, and themes that remain core aspects of onscreen Trek, while its vaunted perfect society doesn’t prevent the Federation, as represented by Captain Jean-Luc Picard (Sir Patrick Stewart) and his intrepid crew, from getting into violent scrapes with the Ferengi, the Klingons, and a Crystalline Entity tied to the backstory of Brent Spiner’s android character Data and Data’s “twin brother,” the prototype android Lore. Perfection certainly doesn’t stop Picard from being supercilious, Worf (Michael Dorn) from being irritable in mostly amusing ways, Dr. Beverly Crusher (Gates McFadden) from knocking down Picard’s haughtiest pronouncements when she finds them unbearable, or Tasha Yar (Denise Crosby) from behaving impulsively as a result of growing up on a failed colony so violent that “rape gangs” were a daily danger.

The Next Generation, in other words, wasn’t afraid to puncture the myth of its own utopianism even when Roddenberry exercised maximum control over its production, meaning that TNG (and the wider Trek franchise) has always included dystopian aspects, as well. The 21st Century Post-Atomic Horror to which John de Lancie’s Q transports Picard, Data, Yar, and Deanna Troi (Marina Sirtis) in “Farpoint,” as well as references to the Eugenics Wars and to World War III in The Original Series, are only a few examples, while the list of corrupt admirals, incompetent officers, lazy bureaucrats, and shiftless ne’er-do-wells encountered by the crews of each Enterprise could (and do) fill several pages (as attested by the many websites and YouTube video essays devoted to Trek’s least-savory people).

As such, it’s always fascinating to see any iteration of Star Trek explore dystopian realms, with voyages to the Mirror Universe being the best known (and, I would argue, best loved). Star Trek: Picard’s superb Season 2 premiere, “The Star Gazer,” concludes with Picard inhabiting just such a world thanks to Q’s ministrations, but its follow-up episode, “Penance,” dramatizes the concept of dystopia so well that, by its conclusion, memories of Picard’s mostly happy life as proprietor of Château Picard’s winemaking operation and Chancellor of Starfleet Academy seem to have occurred several episodes ago, not in the immediately prior installment.

Observing that writers Christopher Monfette, Akiva Goldsman, and new showrunner Terry Matalas (working from a story originated by Season 1 showrunner Michael Chabon) make this terrible journey into darkness both fun and fascinating to watch seems wrongheaded when we consider that Picard, Agnes Jurati (Alison Pill), Raffi Musiker (Michelle Hurd), Seven of Nine (Jeri Ryan), Elnor (Evan Evagora), and Cristóbal Rios (Santiago Cabrera) now inhabit a 25th Century galaxy under the yoke of the xenophobic Confederation of Earth, whose official motto is the distressingly allegorical “a human galaxy is a safe galaxy.”

Picard describes this new reality—where the Confederation brutally conquers alien worlds before enslaving their inhabitants—as “a polluted, totalitarian nightmare” midway through “Penance,” a statement difficult to deny given that “Penance” shows us the Confederation’s dystopian bona fides in scenes that surprise Picard’s characters—no less than its viewers—by enveloping them in a relentlessly despotic future. No other response would be credible given the changes that Goldsman, Matalas, and Monfette sketch with narrative flourishes that build an abundantly imagined world in only 54 minutes.

That’s quite an accomplishment by itself, but “Penance” isn’t content to rest on these laurels. Oh no, as Q tells Picard when the latter accuses him of destroying the Federation’s peaceful society (one that, in the eighteen months since Star Trek: Picard’s first-season finale, has reversed its regressive ban on synthetic lifeforms and worked to ameliorate this policy’s consequences), “Show them a world of their own making and they ask you what you’ve done.” With this line, Q announces a leitmotif that resonates throughout “Penance” and, undoubtedly, throughout the remainder of Season 2. Humanity’s fate is its own creation, meaning that we human beings can’t avoid the consequences of our worst, unchecked impulses.

3. First to Worst

“Penance,” in other words, is an apt title for this second installment. It’s as good as “The Star Gazer,” but moves in different directions. By dramatizing what initially resembles a terrible parallel reality to which Q has consigned our heroes, this entry bears all the trappings of a trip to the Mirror Universe (most recently visited by the crew of Star Trek: Discovery). “Penance,” indeed, doesn’t shy away from depicting what Trek might’ve become had Roddenberry succumbed to literary, cinematic, and televisual science fiction’s predominant modes (and moods) during the 1950s and 1960s: doleful, depressing, and dreary. This installment, put another way, shows us the dystopian Star Trek we’ve seen in drips and drabs throughout franchise history that’ve always been short-lived deviations from Trek’s optimistic vision of the future.

“Penance” promises us a season-long trip to the other side or, at least, an extended stay whose consequences won’t wrap up in one, two, or even five entries. There’s so much to notice and to enjoy that repeated viewings are mandatory, with the relationship between Q and Picard forming the crux of this episode’s good work.

John de Lancie and Patrick Stewart are, once again, aces in their scenes together, with de Lancie shading every line with four or five emotions at once, particularly when Q confesses that he saved Picard from the U.S.S. Stargazer’s destruction, itself initiated by Picard during “The Star Gazer’s” dramatic climax, to make Picard “the very board upon which this game is played.” Considering Q’s later statement that he (Q) is “but a suture in the wound” of Picard’s past mistakes, this game is in fact a life-and-death struggle not merely for Picard’s soul but for the Federation’s entire existence.

“I intervened,” Q explains during his colloquy with Picard, referencing the titles of many previous Trek episodes in a clever bit of intertextual (and even metatextual) awareness. “Oh, how quaint. How provincial. How yesterday’s Enterprise of you,” Q replies to Picard’s question about the fate of the Stargazer’s crew. Perhaps I should transcribe this final sentence as “How ‘Yesterday’s Enterprise’ of you” since Q’s allusion to that terrific third-season TNG episode (which finds the Enterprise-D crew occupying an alternate timeline triggered by a temporal anomaly similar to the one seen throughout “The Star Gazer”) may not break the fourth wall between Picard’s fiction and our reality, but damages it enough that de Lancie need only inflect this line with withering humor rather than winking at the camera.

Q, while showing Picard the study (that doubles as a trophy room) of his bloodthirsty Confederation counterpart (and his empire’s most barbarous military conqueror)—General Jean-Luc Picard, former commander of the C.S.S. World Razer (this new reality’s version of the Enterprise-D)—mentions moving “through a mirror darkly, and, here, the man who holds the glass is darker still.” This first quotation recalls Star Trek: Enterprise’s tremendous Season 4 two-parter “In a Mirror, Darkly,” which follows Scott Bakula’s Jonathan Archer as he schemes to become the Mirror Universe’s emperor, while the second epigram references Star Trek: Deep Space Nine’s touching Season 3 Mirror Universe episode “Through the Looking Glass,” which sees Avery Brooks’s Benjamin Sisko captured by agents of that parallel world’s rebellion against oppression to replace his recently deceased counterpart, who was this resistance movement’s leader.

General Picard’s trophies include battle armor and weapons alongside the skulls of seven prominent extraterrestrial opponents, bringing two more welcome allusions to Deep Space Nine (my favorite Trek program, if not my favorite-ever television series) to the fore. One skull belongs to Gul Dukat, the Cardassian hatemonger, Bajoran conqueror, and psychopath brilliantly embodied by Marc Alaimo during DS9’s seven seasons, while the second belongs to General Martok, the Klingon warrior beautifully performed by J.G. Hertzler in DS9’s fourth, fifth, sixth, and seventh years.

General Picard, Q says, also executed Sarek—Spock’s father and one of the franchise’s most beloved subsidiary characters (played by Mark Lenard in The Original Series, Star Trek III: The Search for Spock, Star Trek IV: The Voyage Home, Star Trek VI: The Undiscovered Country, and two TNG episodes; by Ben Cross in J.J. Abrams’s 2009 movie Star Trek; and by James Frain in Star Trek: Discovery)—on the steps of the Vulcan Science Academy. These examples pile atop so many others that “Penance” overflows with allusions, Easter eggs, and references to Trek’s past, filling my fanboy heart with joy—precisely as Goldsman, Matalas, and Monfette intend—and stoking nostalgia while generating perversely dystopian effects.

A later scene, for instance, mentions “General Sisko,” although the fact that Avery Brooks’s fabulous captain, in this new timeline, leads the Confederation’s xenophobic war against the Vulcans skillfully tempers the momentary delight DS9 fans experience when hearing Sisko’s name spoken aloud. It also squelches the endorphin rush of learning that Sisko is alive in this alternate reality, making his survival into a matter of regret rather than celebration.

“Penance,” indeed, includes so many paradoxical allusions to Star Trek’s rich history that they transcend simple fan service, which would be fine by me even it that’s all they were. Matalas and his collaborators strategically lace these references throughout “Penance” to turn Trek’s foundational principles on their ear, which reaffirms by contrast how important, necessary, and relevant these precepts are for viewers enduring the 2020s, a decade riven by political instability, open warfare, environmental catastrophe, a persistent pandemic, creeping authoritarianism, and noxious white supremacy. The Confederation of Earth, therefore, is Star Trek: Picard’s dystopian warning about what our world might become if we don’t reverse the regressive trends, policies, and ideologies running rampant around the globe.

4. Personal to Political

These concerns make Picard’s second season, in the best Trek tradition, among American television’s most political programs. Admiral Picard is dismayed to learn that he’s this new world’s greatest warmonger, with Stewart sighing, wincing, and casting his eyes downward whenever Q reveals a new detail about General Picard’s legendary cruelty and the Confederation’s bottomless fascism.

Even worse, the Confederation is celebrating Eradication Day—a worldwide paean to liberating humanity from alien influence by committing genocide on a galactic scale—as Q taunts Picard with his (Picard’s) own failures, at one point striking the recalcitrant admiral in the face in another DS9 callback (to Q’s only appearance on that show, in the Season 1 installment “Q-Less,” where Q punches Sisko in the face several times before Sisko, proving that he’s a much different man than Picard, decks Q hard enough to knock this childlike trickster to the floor).

Q’s anger causes Picard to say, “Q, you are not well,” but Q ignores this shrewd comment to throw Picard’s timidity back in his face. “And I’ve had enough of your obstinance, your stubbornness, your insistence on changing in all ways but the one that matters,” Q declares in dialogue that directly interrogates their final exchange in “All Good Things . . .,” The Next Generation’s remarkable series finale.

There, when Picard finally understands the predestination paradox that he himself has created, Q offers hope to the Enterprise-D’s captain in words brilliantly scripted by Ronald D. Moore & Brannon Braga (and wonderfully delivered by de Lancie): “For that one fraction of a second, you were open to options you had never considered. That is the exploration that awaits you. Not mapping stars and studying nebulae, but charting the unknown possibilities of existence.”

Picard’s failure to grow and evolve in this fashion seems linked to his unhappy childhood memories, especially the violence experienced by his mother, as seen in “The Star Gazer.” The penance that Q wishes to extract from Picard is a personal matter with political ramifications for everyone else living in the 25th Century. This truth becomes evident when “Penance” catches us up with all Picard’s Season 1 compatriots save Soji Asha (Isa Briones), who doesn’t appear here (and who may not exist in this new reality).

Seven of Nine awakens in a swank bedroom to discover that she is, in fact, Confederation President Annika Hansen, who was never assimilated by the Borg because this cybernetic species is nearly extinct. President Hansen, moreover, is married to the Confederation’s unnamed Magistrate, the man who functions as her chief of staff, who keeps such close tabs on her that he’s clearly her chief political minder, and who’s well played by Jon Jon Briones (the performer whose musical-theatre credentials include appearing in the original 1989 production of Claude-Michel Schönberg’s, Alain Boubill’s, and Richard Maltby, Jr.’s Miss Saigon, who’s developed into an excellent character actor for film and television, and who's the father of Picard principal cast member Isa Briones).

“Colonel” Cristóbal Rios serves as leader of a squadron of La Sirena-class starships bombarding the surface of Vulcan (all under General Sisko’s command), but heads for Earth when called there by President Hansen. Elnor finds himself in Okinawa, Japan helping a resistance group bomb skyscrapers in retaliation for the Confederation’s wars against Andoria, Cardassia, Qo’noS, Romulus, and Vulcan, but is nearly killed by Confederation security personnel whom Raffi manages to shoot first. Raffi, we learn, is a Confederation officer with enough rank to whisk Elnor away from Okinawa to the Confederation’s San Francisco headquarters, where they reunite with “General” Picard and “President” Hansen.

Despite the dire dystopian world that “Penance” creates, most of this episode’s fun comes from seeing our heroes stumble through the Confederation’s heartless political system by bluffing their way from situation to situation—and moment to moment—while finding their bearings. The Magistrate, however, notices his wife’s altered behavior and begins scrutinizing every facial expression, vocal inflection, and bodily movement while preparing Seven for her annual Eradication Day address. Director Doug Aarniokoski includes brief cutaway shots of the Magistrate’s face to tell a nifty little story about the man’s smart political instincts within this installment’s larger narrative of our heroes adjusting to life in their terrible new existence.

It’s gratifying that Seven and Picard can’t easily hoodwink the Magistrate even as both begin playing their parts as Confederation leaders with greater assurance. The Magistrate remains a shrewd man who, having managed to prosper within the Confederation’s murderous bureaucracy, is nobody’s fool. Jon Jon Briones performs the many different beats required of his character with the wily determination of a skilled apparatchik, relying upon his wonderfully expressive eyes and face to convey just how little the Magistrate comes to trust Seven or Picard.

And where’s Jurati in all this mess? Where else but in her lab, located deep within the bowels of Confederation headquarters, being kept company by an animated cat named Spot 73 that’s voiced by Patton Oswalt? Why not, after all? When Seven and the Magistrate order Jurati to show them the last surviving member of the Confederation’s greatest enemy, whom General Picard will execute later that evening in front of the Eradication Day crowds (in truth, mobs) assembled to hear Seven’s presidential address, both Jurati and Seven are shocked to find this condemned prisoner to be none other than the Borg Queen.

Or, perhaps more accurately, a Borg Queen. We can’t be certain if it’s the same creature that, in “The Star Gazer,” beamed herself onto the Stargazer’s bridge clad head-to-toe in black since this Queen, confined to an isolation chamber, is just a torso that appears much the worse for wear. She’s played to perfection by Annie Wersching, an actress perhaps best known for her role as FBI Agent Renee Walker in Seasons 7 and 8 of Fox Television’s real-time counterterrorist drama 24, but whose very first small-screen part came in the Season 1 Enterprise outing “Oasis” (alongside the late-great Rene Auberjonois, best known to Trek fans as Deep Space Nine’s resident security chief and shapeshifter, the redoubtable Constable Odo).

Wersching makes the Queen, at least in her early scenes, more skittish than either Alice Krige, who originated the role in 1996’s Star Trek: First Contact before playing it again in Star Trek: Voyager’s series finale (“Endgame”), or Susanna Thompson, who was cast as the Queen in three Voyager episodes (the outstanding Season 5 two-parter “Dark Frontier,” the Season 6 finale “Unimatrix Zero,” and the Season 7 premiere “Unimatrix Zero, Part II”).

Wersching’s Queen, mourning the death of her species, is fearful and even morose, although she unexpectedly recognizes Seven as having been previously assimilated into the Borg’s collective consciousness despite President Hansen being fully human. The Queen’s “transtemporal awareness,” as Seven terms it, is an old Star Trek (and science-fiction) standby that gives Picard, once he arrives, the key to understanding how, in the Queen’s words, “time has been broken.”

The Confederation, in other words, isn’t an alternate history or parallel reality to which Picard and company have travelled, but, thanks to Q, their own world monstrously deformed due to what the Queen calls a “temporal recision,” Trekspeak for a single change made to the timeline in the year 2024. Once our heroes realize that they must visit the past to repair the damage done to time, “Penance” becomes a race through some of Star Trek’s most enjoyable narrative conventions. Picard and company must go for broke by planning a last-minute escape (to Rios’s La Sirena), they must play their roles in this dystopian reality well enough to keep the Magistrate and everyone else off balance, and they must depend upon the transporter talents of a single person (in this case, Jurati) to save them from danger.

The episode’s time-is-broken motif implicates not just Trek’s version of time travel but also the series-spanning conspiracy that powered 12 Monkeys (2015-2018), the television program that Terry Matalas co-created and oversaw during its four seasons on the SyFy Channel. Avid viewers of that program already suspected how Star Trek: Picard’s second season might play out when watching “The Star Gazer,” but “Penance” confirms this hunch while melding Monkeys’s temporal calisthenics with the Trek franchise’s many instances of needing to repair the past whenever characters find themselves there.

Picard’s remaining eight episodes seem poised to embrace two potent examples of this plot: the franchise’s fourth (Star Trek IV: The Voyage Home) and eighth (Star Trek: First Contact) feature films. Given the Borg’s significance to the latter, First Contact offers a template for Season 2’s remaining installments. Picard, however, mentions James T. Kirk’s slingshot-around-the-sun maneuver from The Original Series and The Voyage Home to suggest—if not guarantee—many forthcoming allusions to that movie, as well.

“The Star Gazer” sets the table for an excellent season of Star Trek: Picard, but “Penance” offers a scrumptious second course that promises even better entrées to come. In the best Trek tradition, the Confederation’s nightmarish dystopia is magnificently realized here, so averting this fascist future will provide later installments, especially any episode set in 2024, ample opportunities to offer sociopolitical commentary about our present day. “Penance” tells a grand and thrilling adventure despite the terrible new world it creates, so I, for one, can’t wait to see where the writers, cast, and production crew take us next.

NOTE

Herbert F. Solow & Robert H. Justman, Inside “Star Trek”: The Real Story, Pocket Books, 1996.

Marc Cushman with Susan Osborn, These Are the Voyages: TOS Season One, Expanded and Revised Edition, Jacobs Brown Press, 2013.

Mark A. Altman & Edward Gross, The Fifty-Year Mission: The First 25 Years (The Complete, Uncensored, Unauthorized Oral History of “Star Trek”), Thomas Dunne Books, 2016.