Dancing with Denzel

Three decades later, Spike Lee’s Malcolm X remains a powerful, if patriarchal, masterpiece.

Note to The Vestibule’s subscribers: To commemorate the 30th anniversary of director Spike Lee’s 1992 masterwork Malcolm X, I reprint below “Dancing with Denzel,” the third chapter of Spike Lee: Finding the Story and Forcing the Issue, my 2014 scholarly monograph (that’s a fancy way of saying “book”) about one of America’s greatest and most prolific filmmakers.

This essay focuses most of its attention on Malcolm X, although it covers Spike’s first collaboration with actor Denzel Washington, 1990’s Mo’ Better Blues, as an important forerunner to their work on Malcolm X.

Although Chapter 3 mentions Lee’s and Washington’s two excellent later projects, you won’t find any discussion of 1998’s He Got Game or 2006’s Inside Man here. He Got Game receives sustained attention in Chapter 5 (titled “Brooklyn’s Finest”), while Inside Man gets its due in Chapter 7 (titled “Crime and Punishment”).

I’m happy to say that Finding the Story and Forcing the Issue remains available in print and digital formats, so if these movies and/or Spike’s career (up until 2014, at least) interest you, please purchase this book wherever you can find it.

That’s a shameless plug, of course, but if I don’t promote my own work on this humble Substack newsletter, who will?

I offer this chapter here, rather than a brand-new essay devoted to Malcolm X, because my observations and opinions about Lee’s film haven’t changed in the eight years that’ve elapsed since my book’s publication (a span that, yes indeed, prompts the inevitable question “where does the time go?”).

I winced only a few times while re-reading this piece, a response so unexpected that improving this chapter’s thorough analysis of Malcolm X seems unlikely, unnecessary, and unwise. The term thorough is, of course, a polite warning that substantial screen-scrolling awaits you. This piece is a long, long, l-o-o-n-n-n-g-g-g-g haul that may not be quick reading, but that, as the most extensive piece yet published in The Vestibule, I hope is a worthwhile journey.

Scholarly monographs (ahem, “books”—there I go again, running on at the mouth when I should be getting to the point!) thrive on extended paragraphs, but most of this chapter’s paragraphs are so gargantuan that I can’t now explain why I didn’t break them into shorter passages—or why my copyeditors didn’t insist that I do so—before Finding the Story and Forcing the Issue saw the light of day.

As such, I’ve chopped most paragraphs into shorter chunks while aligning this piece with The Vestibule’s house style. Each section, in other words, bears a subheading carried over from the original chapter, while images and links to relevant videos (and other resources) appear throughout this essay.

I’ve resisted the temptation to revise this chapter’s prose (no matter how advisable that action might be) for a simple reason: Once I start, I know I won’t stop until I’ve produced an entirely new essay, which defeats the purpose of posting the original piece here in the first place.

I’ve attached (in the “Files” section) digital copies of “Dancing with Denzel” and Malcolm X’s screenplay. The chapter file includes all research citations and notes alongside Finding the Story and Forcing the Issue’s complete bibliography and complete filmography, while the screenplay, so smashingly written by Spike Lee, originated as a project undertaken by the incomparable James Baldwin.

Difficult as it may be to believe that 30 years have passed since Malcolm X’s theatrical release, here we are. If you haven’t recently seen this Spike Lee joint, encountering it again will provide a remarkable movie-watching experience.

—All the best, Jason

Malcolm X

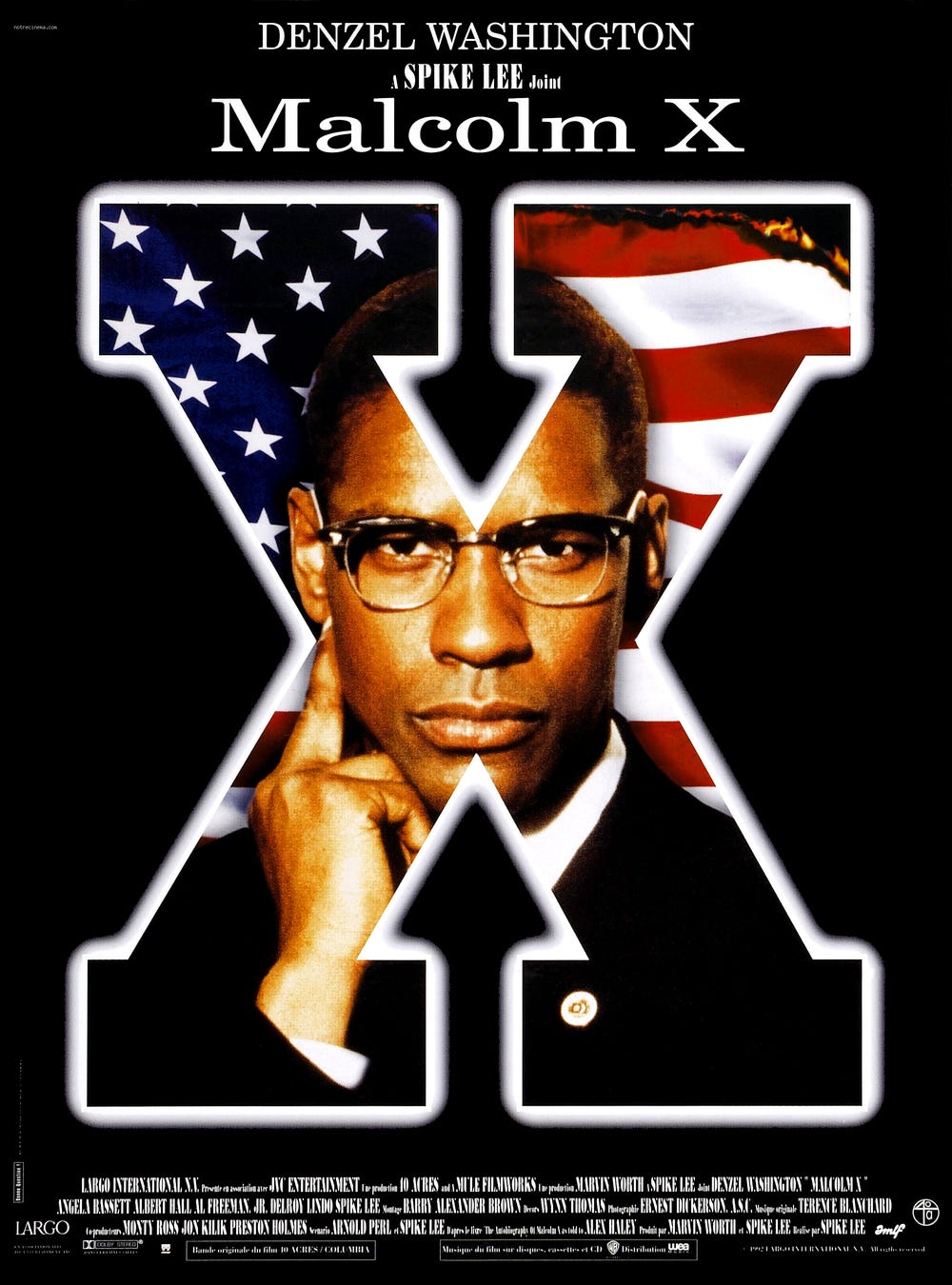

Directed by Spike Lee

Screenplay by Arnold Perl & Spike Lee

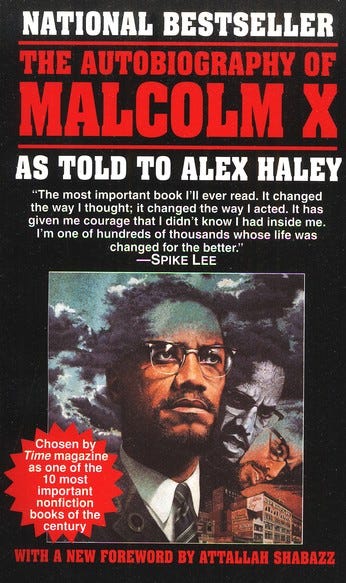

Based on The Autobiography of Malcom X as told to Alex Haley and a screenplay by James Baldwin

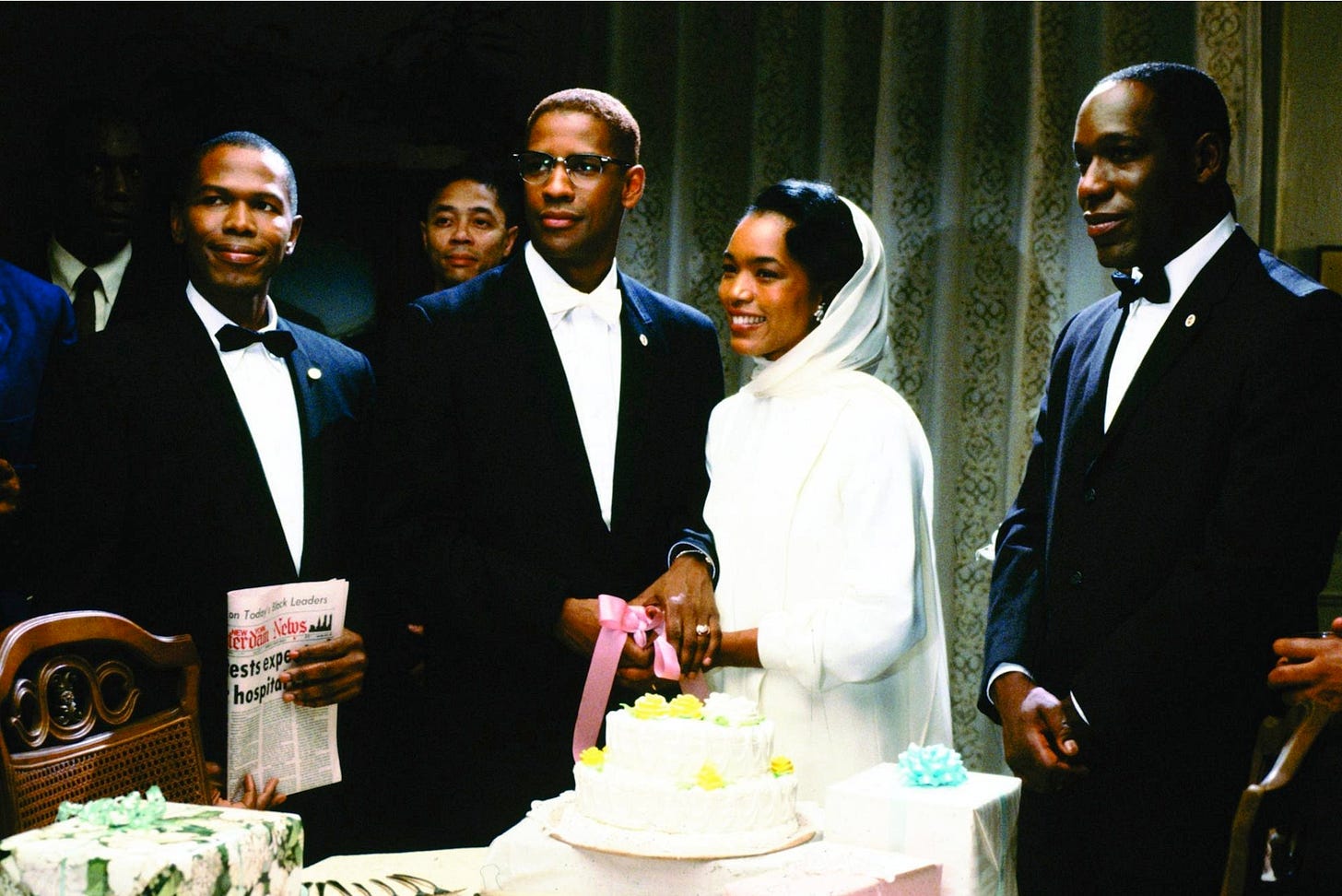

Starring Denzel Washington, Angela Bassett, Giancarlo Esposito, Albert Hall, Tommy Hollis, Spike Lee, Debi Mazar, Lonette McKee, Wendell Pierce, Theresa Randle, Joe Seneca, Roger Guenveur Smith, Kate Vernon, and Al Freeman Jr.

202 minutes

Released 18 November 1992

1. Take the A-Train

For film reviewers, Hollywood observers, and even the director himself, Spike Lee’s four collaborations with Denzel Washington—Mo’ Better Blues (1990), Malcolm X (1992), He Got Game (1998), and Inside Man (2006)—are milestones in their careers. Although these projects tend to confirm each man’s artistic gifts, mainstream discussions surrounding Malcolm X so widely judge this film a landmark accomplishment for American (and African American) cinema that the movie now stands as a masterpiece of early 1990s’ American popular art.

The Library of Congress endorsed this perspective in 2010 by selecting Malcolm X for preservation in its National Film Registry, offering the imprimatur of the organization created by the U.S. Congress to maintain, according to its website, “a list of films deemed ‘culturally, historically or aesthetically significant’ that are earmarked for preservation by the Library of Congress. These films are not selected as the ‘best’ American films of all time, but rather as works of enduring importance to American culture. They reflect who we are as a people and as a nation.”1

The fact that a movie devoted to dramatizing the life of the Black revolutionary once so reviled by the American government that the Federal Bureau of Investigation’s (FBI’s) official surveillance file of Malcolm X runs to more than 5,000 pages2 entered the nation’s official film archive less than twenty years after its theatrical release speaks not only to Lee and Washington’s passion in pursuing Malcolm X’s production but also to Malcolm X’s changing reputation, from frightening critic of American racism, capitalism, and militarism to socially acceptable icon of American dissent, protest, and progress.

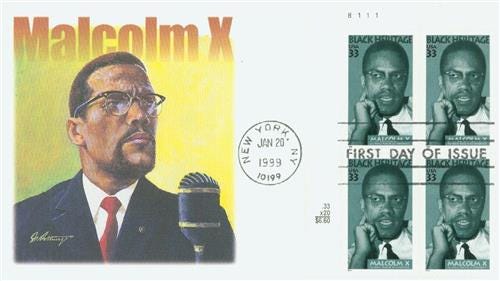

Lee’s cinematic treatment of Malcolm’s life, at least according to the Registry’s mission statement, exhibits such momentous concerns about American history, culture, and politics that Malcolm X tells its viewers fundamental truths about the national experience. The U.S. Postal Service subsequently affirmed Malcolm’s importance by issuing a postage stamp bearing his likeness in January 1999, only six years and two months after Malcolm X’s November 1992 theatrical release.

This event caused actor, activist, and longtime Lee collaborator Ossie Davis—the man whose moving eulogy of Malcolm closes Lee’s film—to comment at the stamp’s unveiling ceremony, “We in this community look upon this commemorative stamp finally as America’s stamp of approval”3 and Attallah Shabazz, Malcolm’s oldest daughter, to write in her foreword to the 1999 edition of The Autobiography of Malcolm X, “This national commemoration, three decades after his lifetime, pays tribute to his immeasurable contributions on behalf of one’s innate right to self-preservation and human dignity.”4

Lee’s film did not directly inspire the stamp’s issuance, but the movie participated in a cultural movement to renew and reclaim Malcolm’s historical significance that began shortly after his assassination on February 21, 1965, that gained traction during the 1970s, and that became a noticeable aspect of African American youth culture throughout the 1980s.

As S. Craig Watkins notes in Representing: Hip Hop Culture and the Production of Black Cinema’s astute discussion of Malcolm X’s production, “And perhaps most important, black youth had created a popular culture based on Malcolm X as a symbol of race pride and cultural resistance. By the early 1990s, the renewed interest in Malcolm X sparked a proliferation of rap songs, caps, T-shirts, books, and posters that saturated the popular cultural world of black youth.”5

Lee, indeed, designed a Malcolm X baseball cap to promote his film long before principal photography began, as he recounts in By Any Means Necessary: The Trials and Tribulations of the Making of “Malcolm X” (While Ten Million Motherfuckers Are Fucking with You!), the movie’s cheekily titled companion publication: “While we were shooting Jungle Fever in late 1990, I made up an initial design for the ‘X’ cap. I’d already decided I had to do Malcolm X, and marketing is an integral part of my filmmaking. So the X was planned all the way out. I came up with a simple design—silver X on black baseball cap.”6

These hats began appearing alongside the T-shirts, posters, books, and songs devoted to Malcolm X that African Americans of all ages, but particularly young people, had embraced in the preceding years, meaning that Lee’s public-relations savvy helped build enthusiasm not only for Malcolm himself but also (and just as importantly) for the film Malcolm X. “The colors could be changed later on as the campaign advanced,” Lee says in By Any Means Necessary, revealing just how deliberately he pursued this marketing strategy: “It looked good. I started wearing it, and we began selling it in our store, Spike’s Joint, and in other places. I gave them away strategically. I asked Michael Jordan to wear it, and he has. Then I asked some other stars to wear it and, what can I say, it just caught on. Then the knock-offs started appearing.”7

Jordan’s assistance was invaluable, particularly when he wore an “X” cap during his televised interview after the National Basketball Association’s 1991 All-Star Game in Charlotte, North Carolina, bringing wide exposure to Malcolm X in an endorsement that, according to Lee’s autobiography, That’s My Story and I’m Sticking to It, made the caps “the must-have accessory of the year.”8

This testament to Lee’s promotional prowess, however, raises the troubling possibility that he crassly commercializes Malcolm’s memory rather than capturing this complex man’s revolutionary life, political philosophy, and social impact onscreen. Watkins, indeed, forthrightly addresses this point by writing, “It was the popularization of Malcolm X and his attractiveness to black youth that both Warner Brothers and Lee sought to exploit”9 in bringing the long-delayed biopic of Malcolm’s life to cinema screens in 1992, although Lee’s commitment to the film throughout its troubled production demonstrates that making Malcolm X was not simply a vanity project designed to generate cash for himself, his collaborators, and his production company.

Yet this concern—expressed before, during, and after Malcolm X’s release by scholars as varied as Amiri Baraka, Clayborne Carson, and Manning Marable10—indicates deeper flaws in Malcolm X, which, while an accomplished film, exemplifies Lee’s problematic representations of Black radicalism, Black militancy, and Black women.

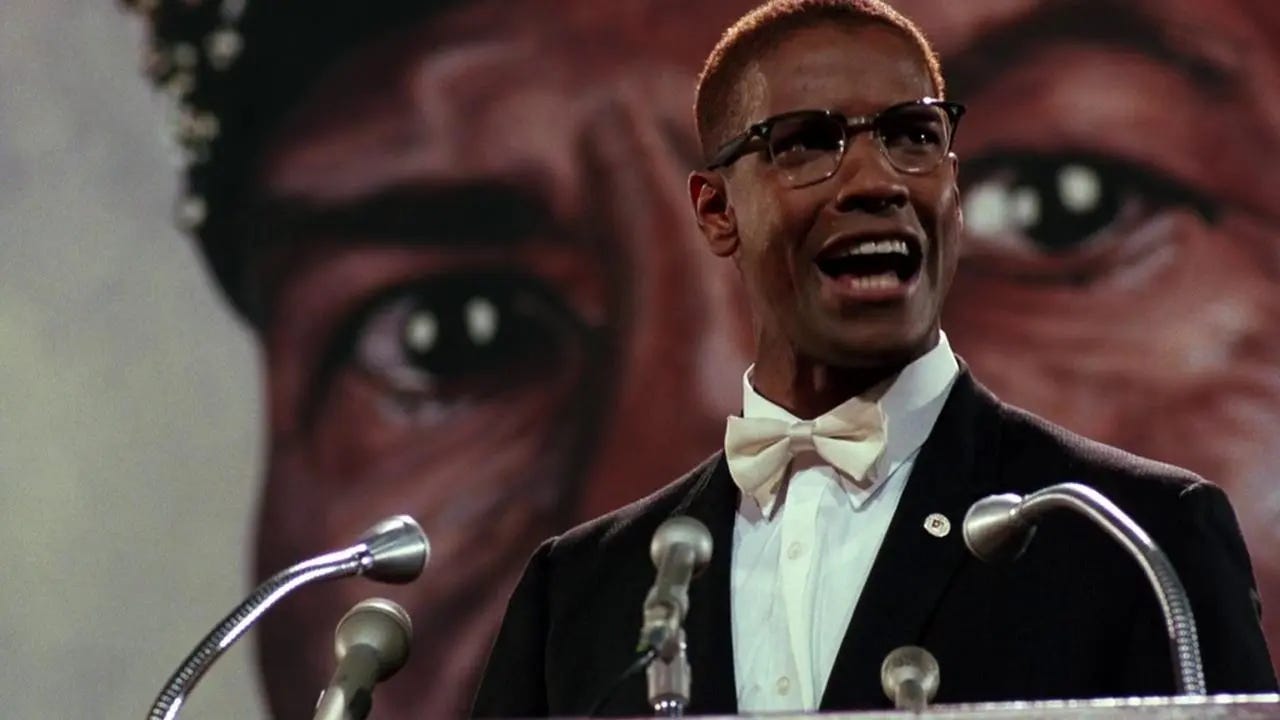

These challenges do not detract from the scale of Malcolm X’s achievement, especially Denzel Washington’s astonishing performance in the title role, Lee’s assured direction, Ernest Dickerson’s admirable cinematography, and Terence Blanchard’s en- gaging score, but they indicate how straitened Lee’s outlook can be when dealing with historically, politically, and culturally charged material.

These drawbacks to an otherwise masterful movie, however, find precursors in Lee and Washington’s first collaboration, Mo’ Better Blues, the story of jazz trumpeter Bleek Gilliam’s professional and personal woes. This movie’s considerable pleasures cannot hide its sometimes distressingly regressive approach to African American women, making it almost a trial run for Malcolm X’s flawed magnificence. Both films are intricate cinematic narratives that evince skillful, dedicated, and passionate craft on the part of their makers, but neither movie can escape the limitations that typify Lee’s early work.

Their blemishes, indeed, are nearly as instructive as their triumphs to demonstrate how Lee’s cinematic vision, like important aspects of Malcolm’s political ideology, is simultaneously revolutionary and traditional.

Both Mo’ Better Blues and Malcolm X are fascinating productions that advance troubling representations of women (particularly African American women) to unite them in a sexist narrative that underscores Lee’s virtues and shortcomings as a filmmaker of provocative subject matter.

2. Blue Notes

Mo’ Better Blues is not merely Malcolm X’s forerunner, but a complicated work of art in its own right. Lee, the son of noted jazz bassist and composer Bill Lee, wrote the film not only to dramatize his appreciation for this music but also in response to three prior movies: Bertrand Tavernier’s Round Midnight (1986), Clint Eastwood’s Bird (1988), and his own Do the Right Thing (1989). Lee confesses in his production notes (compiled in Mo’ Better Blues: A Spike Lee Joint, the film’s companion publication written in collaboration with Lisa Jones), “Not to negate love and relationships, but I don’t think Mo’ Better Blues is as important a film as Do the Right Thing. This doesn’t mean that I like it less—it was the right film for me to do at the time. However, the issue of racism is one I want to explore again on film.”11

Lee’s major interest in creating Mo’ Better Blues, however, involves his marrow-deep love of jazz, perhaps best exemplified by the companion volume’s opening paragraph: “I always knew I would do a movie about the music. When I say the music, I’m talking about jazz, the music I grew up with. Jazz isn’t the only type of music that I listen to, but it’s the music I feel closest to.”12

Although Lee wished to honor his father Bill Lee’s life and career by making a movie about jazz musicians, Tavernier’s and Eastwood’s films inspired him to fashion Mo’ Better Blues as an insider’s view of contemporary jazz artists that avoided the problems he saw in Round Midnight and Bird.

“Both were narrow depictions of the lives of Black musicians, as seen through the eyes of White screenwriters and White directors,”13 Lee writes in the companion volume, while telling Kaleem Aftab in That’s My Story that, despite the fact that both Tavernier and Eastwood might love jazz as much as (and probably know more about it than) he does, the problem with both films is that they offer little warmth, preferring to forward images of tormented musicians who “never laughed, they never had joy in their life, they’re all tragic and torn and twisted.”14

Lee points out that the jazz performers of his generation are not one-dimensional artists condemned to lives of self-destruction by citing Branford and Wynton Marsalis, Terence Blanchard, and Donald Harrison as examples of jazz artists who “weren’t rich, but they were making good money. [T]hey had family, they had girlfriends, had a good time going out, living—they’re not simply moping around lamenting the misery of their lives.”15 Lee, therefore, sees Mo’ Better Blues as a way to correct the cinematic record by offering a broader portrait of African American jazz and blues musicians than Hollywood typically allows, not just in Tavernier’s and Eastwood’s films, but stretching back to Allen Reisner’s St. Louis Blues (1958), Martin Ritt’s Paris Blues (1961), Leo Penn’s A Man Called Adam (1966), and Sidney J. Furie’s Lady Sings the Blues (1972).

Lee’s desire to dramatize the wider experiences of late-twentieth-century jazz artists leads Mo’ Better Blues to repudiate the film cliché of the tragic jazz performer battling his inner demons, especially feelings of artistic inadequacy and commercial failure that lead to drug addiction, by making Bleek Gilliam (Denzel Washington) a disciplined musician and composer involved with two women—aspiring singer Clarke Betancourt (Cynda Williams) and elementary-school teacher Indigo Downes (Joie Lee)—who places his creative life ahead of these (and, truth be told, all other) relationships.

Herein lies the movie’s major problem, for despite this premise’s dramatic potential and the rich terrain that Mo’ Better Blues covers in its best moments, the film does not pay sufficient attention either to Clarke or Indigo as individuals or develop them into autonomous personalities.

As satellites to Bleek’s sexual needs who remain subservient to his artistic pursuits, they are two in a long line of Lee’s hollow female characters. Indigo—despite working as a professional educator (like Lee’s mother, Jacquelyn Shelton Lee) and being well played by his sister, Joie Lee—telegraphs her forgiving nature during her first appearance, when Indigo tells Bleek, after a night of lovemaking, that she should have followed her mother’s advice by not getting romantically involved with a musician, who will bring “grief and pain and tears and heartbreak to my doorstep.” Bleek is “a good brother . . . but you still don’t know what you want” and “a dog . . . a nice dog, but you’re a dog nonetheless.”16

Bleek does not protest these descriptions, but instead utters the film’s most famous (and infamous) line when he tells Indigo, “I’m not gonna argue the point. You know how I am. With men, it’s a dick thing.” This bald, unreconstructed, and bracing declaration of Bleek’s ingrained sexism indicates his adolescent view of romantic relationships. Sex, for Bleek, is merely an anatomical pursuit that reduces both partners to pleasure-seeking fleshpots. He justifies this outlook to his father, Big Stop (Dick Anthony Williams), by telling the older man, simply, “I like women” to explain his refusal to commit to Indigo.

This paradox reveals how Bleek regards Indigo and Clarke less as human beings than as physical bodies that offer sexual stimulation, gratification, and relief, but who retain the potential to disrupt Bleek’s life with emotional considerations that restrict his career ambitions. Bleek, in other words, is a classic sexist who thinks that women, while worthy of physical intimacy, should not intrude into his highly regulated life.

Bleek’s first interaction with Clarke reinforces this point when he chastises her for interrupting his practice session, saying that they might as well make love because she has disturbed his tightly organized schedule. Bleek, indeed, dubs their sexual escapades “the mo’ better” as a comfortable euphemism for coitus that avoids all suggestion of emotional entanglement.

Clarke, no stranger to their relationship’s limitations, accepts her status as Bleek’s casual lover by saying, “We don’t make love because you don’t love me. But in the meantime, I’ll settle for some of that mo’ better.” This capitulation to Bleek’s desire praises his sexual prowess while fortifying Bleek’s view of their relationship as little more than physical release.

Clarke is not upset by this state of affairs, but instead jokes with Bleek about his emotional deficiencies in a scene that, from the perspective of Hollywood’s long history of sexually passive female characters, shows Clarke to be more independent than usual. She is, after all, a woman who pursues physical intimacy with Bleek because it pleases her, not because it ties her to him in more complicated ways.

Lee, indeed, sketches these scenes with good dialogue, while the performances are uniformly excellent. Denzel Washington and Joie Lee are particularly effective, but more intriguing is how first-time actress Cynda Williams infuses Clarke with the subdued eroticism of She’s Gotta Have It’s Nola Darling (Tracy Camilla Johns). Clarke and Indigo, however, are far less interesting than Nola, for however progressive their open sensuality may seem, their willingness to subordinate themselves to Bleek rather than pursuing multiple amorous affairs (like Nola) reveals an ultimately regressive view of women that, despite Lee’s stated commitment to expanding his female characters’ horizons, fails in Mo’ Better Blues.

Clarke may seem to fulfill Lee’s goal when she leaves Bleek for his quintet’s saxophone player, Shadow Henderson (Wesley Snipes), after Shadow offers her the opportunity to sing with the new jazz combo he forms near the film’s conclusion, but, despite Shadow’s charm and Snipes’s good performance in the role, Clarke merely substitutes one domineering man for another.

Bleek, however, loses the ability to play music after his violent encounter with two enforcers, Madlock (Samuel L. Jackson) and Rod (Leonard Thomas). While beating Bleek’s manager, Giant (Spike Lee), for not paying his gambling debts to their boss, the bookie and loan shark Petey (Rubén Blades), Madlock and Rod damage Bleek’s lip by smacking him in the mouth with his own trumpet.

Shadow, having chafed against Bleek’s overbearing control of the Bleek Gilliam Quintet earlier in the movie, takes this opportunity not only to form his own band but also to encourage Clarke’s talent in ways that Bleek (who refuses to let Clarke sing with his combo because she does not have sufficient vocal training) never does. Yet even this beneficence is a sexual scam insofar as the smooth-talking Shadow uses his appreciation of Clarke’s talent as his primary seduction strategy, getting her into bed before giving her the job.

Clarke, true to Bleek’s evaluation, is a passable (but far from terrific) singer who still headlines Shadow’s band, thereby developing greater confidence in her own talent. Indigo, by contrast, becomes less interesting by Mo’ Better Blues’s conclusion. She exercises her own agency by rejecting Bleek when, one night during sex, he mistakenly calls her Clarke, but then mysteriously takes him back when, one year after his injury, the despondent Bleek pleads with Indigo to marry him so that they may start a family. This development suggests that the attractive and intelligent Indigo has had no romantic prospects for the entire year of Bleek’s recovery. She submits to his request because, having no better possibilities, Indigo settles for the now-reformed Bleek, who, no longer pursuing music as either his occupation or avocation, prepares himself for commitment.

The film’s unlikely conclusion sees Bleek and Indigo marry, have a son named Miles (Zakee Howze), and live as a reasonably happy middle-class family in the same brownstone that served as Bleek’s childhood home. This denouement demonstrates Mo’ Better Blues’s essential sexism, for Indigo surrenders to marriage and motherhood with scant motivation. Indeed, only her physical attraction to Bleek explains Indigo’s willingness to accept his questionable confession of love, which, in truth, is merely his plea for Indigo to fulfill him because music no longer can.

Treating the film’s female characters so cavalierly weakens Lee’s approach to Mo’ Better Blues despite the movie’s other merits, setting a path that Malcolm X follows. As bell hooks notes in “Male Heroes and Female Sex Objects: Sexism in Spike Lee’s Malcolm X,” her caustic review of the latter film, “it is Mo’ Better Blues that sets paradigms for black gender relations. Black females are neatly divided into two categories—ho’ or mammy/madonna. The ho’ is out for what she can get, using her pussy to seduce, conquer, and exploit the male. The mammy/madonna nurtures, forgives, provides unconditional love.”17

Creating such stereotypical women strands Lee’s male protagonists in an untenable situation that, for hooks, reinforces the director’s worst propensities: “Black men, mired in sexism and misogyny, tolerate the strong, ‘bitchified,’ tell-it-like-it-is black woman but also seek to escape her. In Mo’ Better Blues, the black woman who gets her man in the end does so by surrendering her will to challenge and confront. She simply understands and accepts. It’s a bleak picture. In the final analysis, mo’ better is mo’ bitter.”18

This evaluation perceptively identifies Mo’ Better Blues’ major flaw, which Malcolm X both extends and revises by including female characters—especially Malcolm’s wife, Betty Shabazz (Angela Bassett)—who, despite their intelligence and dignity, remain satellites to the protagonist’s quest for political and personal liberation. Although hooks sees both movies as victims of Lee’s cinematic chauvinism, this underlying truth misses the political, cultural, and sexual complexities that make Mo’ Better Blues and Malcolm X worthwhile films to watch.

Both movies are revolutionary and traditional, progressive and regressive, liberatory and restrictive texts that cannot be reduced to simple failures of vision because they chronicle, with occasional insight, the problematic African American masculinities so typical of Lee’s most provocative productions.

3. Reel Women

Lee’s difficulties with female characterization help explain why Malcolm X is such a patriarchal film, a reality with precedent in The Autobiography of Malcolm X that Lee’s movie accentuates by sidelining or omitting significant women in Malcolm’s life.

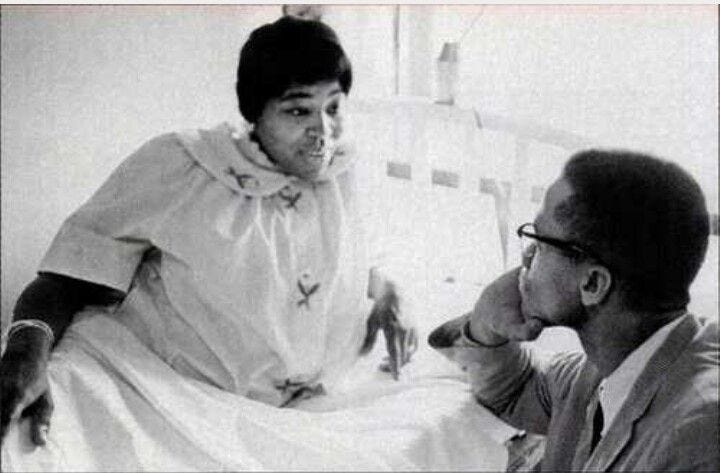

Malcolm’s mother Louise Norton Little (Lonette McKee), like his father Earl Little (Tommy Hollis), appears only in flashbacks, where, in her first appearance, the pregnant Louise attempts to protect her children (including the unborn Malcolm) from Ku Klux Klansmen who break all the windows of their Omaha, Nebraska house when the Klansmen realize that Earl, an itinerant preacher and supporter of Marcus Garvey whom they blame for inciting local African Americans to become “uppity,”19 is not at home. Louise’s subsequent appearances become shorter and more disturbing, until, after moving with Earl to Lansing, Michigan, she endures the indignities that follow his violent death (Earl is run down by a trolley car after being attacked by men belonging to the Black Riders, a local racist militia).

Louise fights the life-insurance company that refuses to honor Earl’s policy after judging his death a suicide, protests the visits of social worker Miss Dunne (Karen Allen) as intrusive and racially insensitive, loses control of her family, sees her children become wards of the state, and, finally, sits prostrate and unmoving in the Kalamazoo mental hospital to which she is forcibly committed.

These vignettes follow the Autobiography’s narrative sequence, bringing Louise to vivid life (McKee is excellent in the role), but devote less attention to her than Malcolm’s book, even allowing for the narrative compression necessary to adapt the Autobiography into a three-hour, twenty-two-minute movie. Malcolm X, in a serious omission, fails to dramatize the domestic violence that Louise suffered at Earl’s hands, violence that Malcolm describes in resolutely sexist terms.

The Autobiography’s first chapter, for instance, notes that Malcolm’s parents “seemed to be nearly always at odds. Sometimes my father would beat her. It might have had something to do with the fact that my mother had a pretty good education. Where she got it I don’t know. But an educated woman, I suppose,” Malcolm writes in a passage revealing his patriarchal beliefs, “can’t resist the temptation to correct an uneducated man. Every now and then, when she would put those smooth words on him, he would grab her.”20 This statement, one of many in the Autobiography to expose Malcolm’s entrenched sexism, prepares the reader for his eventual recognition of women’s importance to the Black freedom struggle, both in America and in Africa’s newly independent nations.

Lee’s exclusion of this material, however, deprives Malcolm X of a key flashback that would help contextualize Louise’s mental breakdown not simply as the product of racial discrimination, but as the culmination of long-term racial and gender inequality that, when coupled with the stress of raising seven children alone, provokes the depression and despair that Malcolm’s Autobiography forlornly documents. Scrubbing Earl’s violence against his wife from the film may seem to offer Louise more agency than the Autobiography permits, but this decision restricts her character to a common stereotype: the wild-eyed Black mother incapable of caring for her children.

Malcolm’s cinematic voiceover, taken from the Autobiography, notes that, “if ever a state agency destroyed a family, it destroyed ours” in Lee’s effort to capture the sexist-yet-sympathetic portrait of Louise Little that the Autobiography’s first chapter conveys. Observations (in the book) such as “Nothing that I can imagine could have moved me as deeply as seeing her pitiful state”21 are particularly poignant. Lee visually suggests this comment by having the adult Malcolm sit in a corner of Louise’s hospital room with his face (in one of Denzel Washington’s finest moments) covered by appalled regret, but Lee still chooses not to dispute the Autobiography’s patriarchal treatment of Louise.

Jeffrey B. Leak, in his cogent essay “Malcolm X and Black Masculinity in Process,” agrees with Hilton Als’s assessment (propounded in Als’s article about the Autobiography’s treatment of Louise Little, “Philosopher or Dog?”) that Louise “only serves two purposes for Malcolm: to give birth to him and to symbolize the stain of white blood on the Negro race”22 because, as a light-skinned Black woman, she offers visual proof of the historical crime of white masters raping their female slaves.

Leak points out that, in the Autobiography, “Malcolm objectifies her, rendering her as nothing more than an extension of white supremacy and colonialism. He is able to explain why his father would strike her, but he fails to explain or consider the notion that his mother had a right to offer an opinion (and even a criticism) when necessary.”23 Failing to challenge more forcefully this sexist depiction of Louise in Malcolm X demonstrates that Lee, at least in this instance, remains more concerned about faithfully rendering the Autobiography’s chauvinistic view of women than offering a broader portrait of Louise.

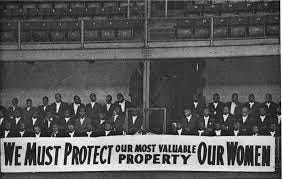

Lee’s interest in her, like Clarke and Indigo in Mo’ Better Blues, remains more symbolic than realistic. Louise, indeed, becomes the first woman to disappoint Malcolm and, consequently, the model upon which he bases his future opinions of women, making him receptive, once he becomes a member of the Nation of Islam (NOI), to the Nation’s strict ideology that the sexes should inhabit separate spheres; that women are, in the words of the memorably troubling NOI rally banners that Malcolm X reproduces in two different scenes, Black America’s “most valuable property”; and, most famously, that women should confine themselves to submissive, nurturing roles that revolve around husbands and children rather than independent lives, ambitions, and careers.

Leak’s analysis shows that Malcolm’s attitudes toward women were not static despite the patriarchal affirmation they received once he joined NOI. Any detailed reading of the Autobiography exposes the considerable understatement Leak indulges when writing, “Malcolm certainly began his ruminations about his life with, at best, a deep indifference toward women,”24 yet Leak correctly observes that Malcolm’s relationship with his half-sister and eventual guardian, Ella Little-Collins, “depicts Malcolm’s struggle with patriarchy and his willingness to reveal his rather narrow-minded views about women, perspectives that by the end of the Autobiography are in the process of reformulation but far from complete revisions.”25

Ella takes Malcolm into her home when he relocates to Boston’s all-Black Roxbury neighborhood; offers him guidance about life as a young African American man; succeeds in transferring him from the Charlestown State Prison to the Norfolk Prison Colony (described by the Autobiography as “an experimental rehabilitation jail”26) after Malcolm is arrested for burglarizing Boston homes and sentenced to ten years imprisonment; finances his 1964 trip to Mecca, during which he undergoes spiritual transformation while on hajj; and, after his death, helps preserve Malcolm’s legacy by running the Organization of Afro-American Unity that Malcolm founded less than one year before his assassination.

Malcolm explains Ella’s immense effect on him by commenting in the Autobiography that, during their first meeting, Ella visits his family in Lansing, where he notices that “she was the first really proud black woman I had ever seen in my life. She was plainly proud of her very dark skin. This was unheard of among Negroes in those days, especially in Lansing.”27 Ella’s dignified bearing, however, cannot overcome Malcolm’s sexist appraisal of her when he arrives in Boston to find that Ella has prepared a room in her Roxbury home for him.

The Autobiography, in a pattern that typifies Malcolm’s depiction of Ella and other independent women, mingles praise with skepticism about unconventional female lives. “Ella still seemed to be as big, black, outspoken and impressive a woman as she had been in Mason and Lansing,” Malcolm says, but then reveals, “Only about two weeks before I arrived, she had split up with her second husband . . . but she was taking it right in stride. I could see, though I didn’t say, how any average man would find it almost impossible to live for very long with a woman whose every instinct was to run everything and everybody she had anything to do with— including me.”28

Malcolm, by indicating that only extraordinary men can tolerate strong-willed women like his half-sister, repeats the sexist canard that proper female behavior defers to men rather than challenges male authority. Average men, the Autobiography implies, find Ella (and women like her) so intimidating that the emasculating potential such women represent strikes fear in them. Malcolm, in the passage’s most significant subtext, feels just as threatened as Ella’s husband despite admiring her race pride. He refuses to contemplate how Ella’s strong will enhances her compassion for him, which, rather than dominating Malcolm into submission, instead protects him for several years from the vicissitudes of growing up as a ne’er-do-well young Black man in Boston.

Ella becomes Malcolm’s surrogate mother, who, as bell hooks notes, “helped educate him for critical consciousness,”29 but also ensured that Malcolm would rebel against her influence. Ella’s significance as a symbol of assertive Black femininity appears at key junctures throughout the Autobiography to illustrate, just as Jeffrey B. Leak argues, that, despite the book’s persistent chauvinism, Malcolm’s patriarchal view of women is not so ironclad that it resists all modification.

Malcolm X, however, eliminates Ella from its cinematic narrative. This elision prevents the film from demonstrating how crucial she was to Malcolm’s development, particularly how his time as a hustler, as a sexually promiscuous criminal who parades his white girlfriend Sophia (Kate Vernon) throughout Harlem and Roxbury, and as an NOI minister preaching sexism under the guise of Muslim propriety contradicts Ella’s example and approbation.

Her presence is a vital component of Malcolm’s life that Lee’s movie avoids to maintain its resolutely patriarchal character. This aesthetic decision, in hooks’s estimation, allows Lee “to create a film that does not break with Hollywood conventions and stereotypes,” which, true to form, remain invested in portraying “the super-masculine hero . . . as a loner, an outlaw, a cultural orphan estranged from family and society.”30 Erasing Malcolm’s relationship with Ella and marginalizing his relationship with Louise transform Malcolm X into a masculine fantasy that hooks finds not merely regrettable, but fully objectionable.

“To have shown the bonds between Ella and Malcolm which were sustained throughout his life,” hooks writes, “Lee would have needed both to break with Hollywood representations of the male hero as well as provide an image of black womanhood never before imagined on the Hollywood screen. The character of Ella would have been a powerful, politically conscious black woman who could not be portrayed as a sex object.”31

This damning assessment recognizes how thoroughly Lee rewrites Malcolm’s life to emphasize the masculine stereotypes that align Malcolm X with the Hollywood biographical pictures (biopics) that Lee both emulates and revises. Choosing Malcolm as the subject of such a film expands the biopic’s traditional boundaries, since no previous studio-backed movie of Malcolm X’s scale had tackled the life of an African American revolutionary leader (cinematic portrayals of Nat Turner, Frederick Douglass, Martin Luther King, Jr., Medgar Evers, and Huey P. Newton restricted them to supporting roles in theatrical films or to the subjects of television movies and miniseries), yet respects the genre’s conventions by making the protagonist a dominant male who interacts with women on his own terms and as he pleases.

Reducing Louise Little’s presence and eliminating Ella Little-Collin’s role in Malcolm X not only extend the problematic representation of women in Lee’s earlier films but also repeat Mo’ Better Blues’s depiction of women as either irritants or accessories to the protagonist’s unquestioned masculinity.

4. Biopics, Bitchery, & Betty

Malcolm X’s debt to the biopic, however, helps account for its patriarchal attitude. Thomas Doherty’s insightful essay “Malcolm X: In Print, On Screen” carefully analyzes the links between Lee’s film and the genre that proves so influential to his narrative choices. “Just as The Autobiography of Malcolm X was read by the light of classic American literature,” Doherty writes, “Malcolm X unspooled in the shadow of one of Hollywood’s most durable motion picture genres: the biopic. During the classical studio era, the biopic thrived by celebrating the great (white) men of science, politics, and the arts, and the loyal women who stood behind them.”32

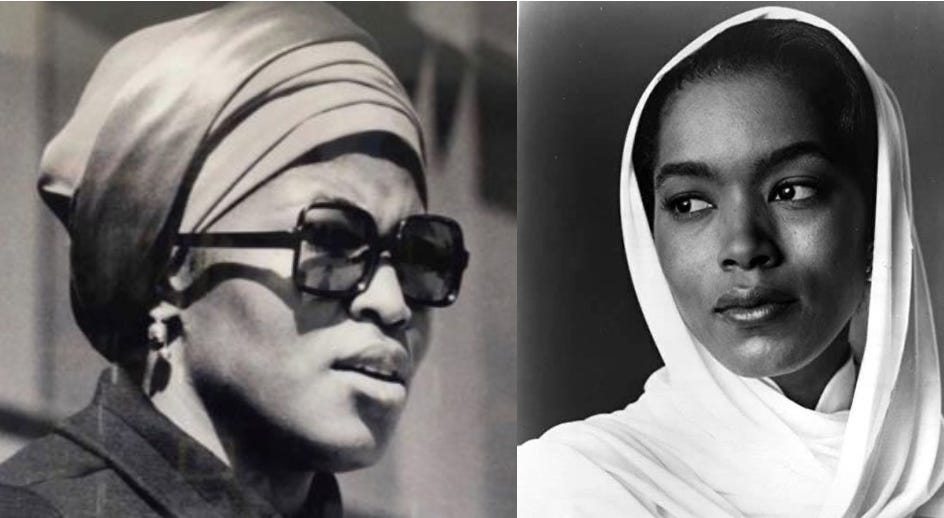

This final clause well describes Malcolm X’s depiction of Betty Shabazz, Malcolm’s charming and intelligent wife, as a woman who occasionally prods him to be a better provider for his growing family and who, in a powerful scene, forces Malcolm to question the moral rectitude of NOI leader Elijah Muhammad (Al Freeman, Jr.) when reports of Muhammad’s infidelities with NOI secretaries surface.

Angela Bassett so beautifully plays Betty that the woman’s status as a doting spouse might escape the viewer’s notice when first watching the film, but Bassett-as-Betty contradicts the image that bell hooks advocates in “Male Heroes and Female Sex Objects” of a woman who “seduces and traps” Malcolm into marriage and who “‘reads’ her man in the bitchified manner that is Lee’s trademark representation of heterosexual black coupling.”33 Betty neither appears in enough scenes to justify the charge of seduction nor pursues Malcolm in the open, sensual, and aggressive manner of Sophia, who, early in Malcolm X, offers herself to him at Boston’s Roseland Ballroom after the frenetic and exceptionally well-choreographed Lindy Hop dance number that becomes the film’s first show-stopping set piece.

Despite hooks’s generally acute assessment of Malcolm X’s sexism, she misreads Betty’s character as a temptress when neither Lee’s direction nor Bassett’s acting substantiates this conclusion, especially considering that Betty’s earnest interest in Malcolm’s welfare (visible during their first meeting at one of Malcolm’s public speeches, during their later meal at a Muslim cafeteria where Malcolm lectures Betty about women’s deceitful ways, during a subsequent trip to New York’s American Museum of Natural History, and during their visit to a diner where they share ice-cream sundaes) remains so chaste that Betty barely registers as a sexual presence, to say nothing of Malcolm’s marriage proposal, which he makes from a Detroit phone booth in what may be the least romantic scene of a man asking a woman to join him in matrimony ever depicted in an American studio film.

Betty instead so perfectly fulfills the biopic’s stock role of faithful spouse to a man destined for greatness that only her race and Bassett’s terrific performance distinguish Betty from the trustworthy wives who appear in dozens of earlier Hollywood biopics. Malcolm X, in other words, captures the Autobiography’s conservative view of women, especially Black women, with Betty standing as a symbol of strength, dignity, and submission in both book and film.

Sheila Radford-Hill addresses the realities of Betty’s life in her important essay “Womanizing Malcolm X” by noting, “Betty Shabazz was a well-educated black woman who was willing to conform to the Black Muslim feminine ideal,” being “one of the many Muslim women who did not outwardly defy their husbands as their behavior was intimately connected to their religious conviction.”34 Betty, however, was no wilting flower, as her friend Myrlie Evers-Williams (widow of Medgar Evers) writes in her foreword to Russell J. Rickford’s biography Betty Shabazz, Surviving Malcolm X, describing Betty as a “highly unusual woman of strength and courage”35 who learned “how to survive heartache, self-doubt, anger, bitterness, and personal growth”;36 who once told Evers-Williams, “My children think my persona is me, when actually it is their father’s”;37 and “who was complex and yet simple in her wisdom.”38

These comments and Rickford’s well-researched book demonstrate that Betty was a complicated person who, despite her intellectual independence, accepted NOI’s teachings about women out of religious faith. Radford- Hill explains this seemingly contradictory outlook by writing, “Women like Betty Shabazz respected the Nation’s masculine ideal as it offered provision, protection, honor, and respect for black women who had an important, though subordinate, role in building the black nation.”39 Betty’s religious commitment to Islam, indeed, began as dedication to NOI, but underwent a similar transformation to Malcolm’s when she left the Nation with him in 1964, made pilgrimage to Mecca in 1965 (after Malcolm’s assassination), embraced Sunni Islam, and returned to the United States to earn master’s and doctoral degrees while raising six daughters.

Lee’s movie depicts some of this strength, as well as Betty’s understated sense of humor, when, during Malcolm’s lecture about women’s wicked ways, Angela Bassett’s fine acting comes to the fore. Betty smiles skeptically, knowingly, and sweetly in the same moment before commenting, “I think you’ve made your points, Brother Minister Malcolm. You haven’t any time for marriage,” causing the rueful Malcolm to laugh.

Denzel Washington and Bassett play this scene not only with the tentative affection appropriate to a couple just learning about one another but also with the warmth that characterizes their companionable marriage later in the film. Most notable, however, is Bassett’s talent at communicating Betty’s inner strength and determination by subtly challenging, rather than directly contradicting, Malcolm’s (and Elijah Muhammad’s) overbearing sexism.

Lee’s film, in this and other scenes, follows the Autobiography’s lead by depicting Betty as “a good Muslim woman and wife”40 about whom Malcolm, in one of the book’s most revealing passages, writes, “I guess by now I will say I love Betty. She’s the only woman I ever even thought about loving. And she’s one of the very few—four women—whom I have ever trusted.”41 This hesitant declaration (“I guess by now I will say I love Betty,” not “I love Betty”) comes after Malcolm mentions their four daughters by name to suggest that Betty’s status as mother of his children, not her other qualities, convinces him to love and trust her.

Malcolm immediately expands this portrait by noting that what he calls the “Western ‘love’ concept . . . really is lust. But love transcends just the physical. Love is disposition, behavior, attitude, thoughts, likes, dislikes—these things make a beautiful woman, a beautiful wife. This is the beauty that never fades,” meaning that actual love appreciates deeper merits in a woman and should not wait until her “physical beauty fails”42 to declare itself. Malcolm’s fascinating but troubling perspective here recommends a spiritual connection between husband and wife that sees beyond a woman’s surface appearance in what resembles a laudable attempt to appreciate women in general—and Betty in particular—for their strength of character, but that nonetheless privileges masculine control.

Malcolm, after all, neither enumerates the qualities that make a beautiful (or handsome) husband appealing to his partner nor considers how a man’s failing appearance might make him less attractive to his wife. Malcolm’s most egalitarian statement about such relationships comes via religious explanation: “But Islam teaches us to look into the woman, and teaches her to look into us.”43

Yet this declaration also takes for granted a man’s privilege in evaluating a woman’s life, character, and potential, raising him to an unchallenged position by employing the plural term us to implicate Malcolm, his amanuensis Alex Haley, and his reader in a narrative that constructs its audience as male to help Malcolm relate his (and NOI’s) conviction about women’s subordination. By citing Betty as a specific example of a woman who fulfills the roles of good wife and mother for the benefit of all African Americans, Malcolm’s effort to reframe his sexist assumptions merely helps to reinforce them.

Seeing into a person is one of the Autobiography’s central metaphors for developing a secure understanding of another human being’s beliefs and attitudes. It also cements NOI’s foundational sexism. Malcolm later states that, because Betty looks into him as Islam teaches, “so she understands me. I would even say I don’t imagine many other women might put up with the way I am. Awakening this brainwashed black man and telling this arrogant, devilish white man the truth about himself, Betty understands, is a full-time job.”44

Betty’s forbearance and patience are prime values for Black women to adopt if they wish to support their husbands in liberating African Americans from the political, economic, and social bonds that restrict them. These virtues demand, as Radford-Hill recognizes, “submissiveness and single-minded attention to the care and nurture of black children, the fruit of the black nation”45 that defines NOI’s feminine ideal, a mindset that Malcolm wholeheartedly adopts during his time as the Nation’s most visible spokesperson, both in the Autobiography and in Malcolm X.

This patriarchal view so typified Black-nationalist pronouncements about the freedom struggle during the 1950s and 1960s that Radford-Hill analyzes the sociopolitical context in which Malcolm made similar statements, not to excuse his sexist (and occasionally misogynistic) opinions, but to understand how they developed within the larger systems of thought, behavior, and culture that affected Malcolm’s political stance. Writing that “black feminist and womanist scholars have long recognized that black nationalism promoted a pernicious machismo,”46 Radford-Hill reminds her reader that research into the factors surrounding NOI’s conservative sexual roles permits readers of the Autobiography (and viewers of Malcolm X) to understand the loyalty of NOI women to Elijah Muhammad’s doctrine of female submission, for, in perhaps Radford-Hill’s most important insight, “feminists and womanists have also exposed how patriarchal dominance manipulates female expectations of men to enforce gender codes favorable to male interests.”47

Malcolm X and Betty Shabazz were as captive to these codes as anyone else, while the passages in Malcolm’s Autobiography about Betty’s exemplary behavior become, in this light, interventions in their era’s gender discourse that fortify patriarchal understandings of women’s proper roles relative to masculine authority.

Critical readers may even say that Malcolm manipulates theses gender codes to reinforce his reputation as a fearless truth-teller and to enhance his image as the strong male who keeps his wife in line, but Radford-Hill notes this image’s nuances by writing, “another aspect of gender research involves how black manhood is constructed and performed. The short history of Malcolm’s manhood suggests that his family provided examples of determined black women and that as he developed politically, he remade his masculine subjectivity in ways that allowed him to see women as agents of social change.”48

This judgment becomes clear to anyone who studies Malcolm’s final year when, after two 1964 trips to Africa, he becomes impressed by how forcefully women play roles in the decolonization movements that, beginning in the 1950s, swept the continent, with seventeen African nations achieving independence from European colonial powers and becoming United Nations member states in 1960 alone.49

Malcolm, indeed, says during a 1964 interview conducted in Paris, France, after his second African visit, “One thing that I became aware of in my traveling recently through Africa and the Middle East, in every country that you go to, usually the degree of progress can never be separated from the woman. If you’re in a country that’s progressive, the woman is progressive.”50

He elaborates this theme, saying, “If you’re in a country that reflects the consciousness toward the importance of education, it’s because the woman is aware of the importance of education,” enabling him to repudiate the Autobiography’s and NOI’s pervasive sexism by concluding, “So one of the things I became thoroughly convinced of in my recent travels is the importance of giving freedom to the woman, giving her education, and giving her the incentive to get out there and put that same spirit and understanding in her children,” even going so far as observing, “And I frankly am proud of the contributions that our women have made in the struggle for freedom and I’m one person who’s for giving them all of the leeway possible because they’ve made a greater contribution than many of us men.”51

These words demolish many of Malcolm’s earlier regressive statements about women, including declarations laced throughout the Autobiography. This single interview response, of course, cannot undo the damage inflicted by years of preaching NOI’s sexist ideology, but Radford-Hill recognizes that, although “Malcolm X internalized masculine regimes or attitudes, values, and beliefs about manhood based on cultural norms, race consciousness, religious identity, and the social norms of the urban working class,”52 he also worked with many forthright, assertive, and independent women—including Maya Angelou, Ruby Dee, Shirley Graham Du Bois (widow of legendary Black intellectual and activist W.E.B. Du Bois), Fannie Lou Hamer, Coretta Scott King, and his half-sister Ella Little-Collins—after leaving NOI.

He also “recruit[ed] such women as Lynne Shifflett, Muriel Feelings, and Alice Mitchell to play key roles in the early development of the Organization of Afro-American Unity.”53 These professional relationships demonstrate Malcolm’s evolving perspective about the place, potential, and role of Black women in the freedom struggle, an outlook that was by no means complete at the time of his death, but that indicates the growing distance between the sexism of Malcolm’s NOI years and his enlightenment about issues of gender, sexism, and feminism that began transforming Malcolm’s views during his final months of life.

Malcolm X, however, does not dramatize this shift in Malcolm’s attitudes, but instead portrays his sincerely held conviction that Elijah Muhammad’s infidelities illustrate the older man’s personal failings more than the systemic sexism propagated by NOI’s severe (and, in Muhammad’s case, hypocritical) gender ideology.

This failure fortifies the patriarchal attitudes that Malcolm displays throughout the film, causing bell hooks to write that Lee’s choice to underplay Malcolm’s changing views of women “creates a version of black political struggle where the actions of dedicated, powerful, black female activists are systematically devalued and erased. By writing Ella out of Malcolm’s history, Spike Lee continues Hollywood’s devaluation of black womanhood.”54 This assessment suggests that Malcolm X’s fealty to the Autobiography’s provincial regard for women demonstrates Lee’s commitment to rendering faithfully Malcolm’s influential text for moviegoers who may never have read the book (or never have finished it).

Abolishing Ella from Malcolm X’s narrative is, therefore, a curious oversight given Lee’s repeated public pronouncements about wanting to get Malcolm right, although Lee, during his long interview with Henry Louis Gates, Jr., about the movie’s production titled “Generation X,” defends this choice by saying, “Our intention is not to tear down Malcolm; for us this is an act of love. And in those cases where we had to change names, change events, or make three or four characters into one, well, I don’t think that’s distorting the Malcolm X story. You have to realize we’re not making a documentary, we’re making a drama,”55 which, in Lee’s mind, justifies significant omissions: “Ella Collins is not in this film; Farrakhan is not in this film; you don’t have Reginald [Malcolm’s brother] introducing him to Islam in this film. So you’ve got the same problem as a filmmaker adapting a vast novel to the screen. You can’t include everything; some things you switch or turn around.”56

Lee also neglects including Alex Haley and Malcolm’s adult siblings as characters, thereby giving the impression that Malcolm not only worked in isolation from meaningful human contact but also endured the political and personal setbacks depicted throughout Malcolm X alone. This portrayal conforms to the traditional biopic’s fascination with active, assertive, and aggressive men who require few emotional connections to achieve their destiny, extending the American fascination with rugged individualism into cinematic myth.

Lee’s proclamation that the temporal limitations of even this epic film govern aesthetic choices that he makes out of love, however, ignores the antifeminist implications of deleting so many important women from Malcolm X. The confluence of Lee’s patriarchal depiction of Malcolm’s life and the biopic’s preference for lone-wolf heroes (who affirm their masculinity by secluding themselves as much as possible from female influence) reduces the movie’s effectiveness despite its excellent performances, direction, set design, musical score, and cinematography.

Angela Bassett’s admirable turn as Betty Shabazz and Kate Vernon’s effective performance as Sophia cannot overcome Malcolm X’s backward attitude toward women, which was far from inevitable given the project’s disputatious production history and James Baldwin’s early work as its screenwriter. The film’s difficulties with female characters in some measure mirror its political hesitance about presenting Malcolm’s most radical ideas, especially after his break with NOI, but these problems do not condemn Malcolm X to irrelevance.

While remaining a praiseworthy accomplishment for Lee and his collaborators, the film’s political inhibitions, no less than its feminist implications, prevent Malcolm X from becoming the groundbreaking production that its most fervid admirers believe, but also far from the outright failure that scholars such as bell hooks and Amiri Baraka proclaim.

5. Rage, Revolution, & Redemption

No single film devoted to Malcolm X could dramatize every important individual, incident, and intention documented in the Autobiography, to say nothing of Malcolm’s entire life. Doing so would require a long-running television series staffed by writers willing to reconcile the Autobiography’s claims with the vast scholarship about Malcolm that has developed since his 1965 assassination (including two controversial biographies, Bruce Perry’s Malcolm: The Life of a Man Who Changed Black America and Manning Marable’s Malcolm X: A Life of Reinvention), the many memoirs published by people who knew or were influenced by Malcolm (including his third daughter Ilyasah Shabazz’s Growing Up X: A Memoir by the Daughter of Malcolm X and his nephew Rodnell P. Collins’s Seventh Child: A Family Memoir of Malcolm X), and the massive government surveillance files of Malcolm available at the FBI’s official website (and in Clayborne Carson’s book Malcolm X: The FBI File, with an introduction written by Spike Lee).

The scope of this imaginary project increases any critical viewer’s appreciation for Lee’s achievement in making Malcolm X a quarter century after producer Marvin Worth first optioned the rights to The Autobiography of Malcolm X in, depending upon which source one consults, 1967 or 1968.57 That Lee was only ten (or eleven) years old when Columbia Pictures first considered bringing Malcolm X to cinematic life illuminates how Malcolm’s contested reputation, controversial image, and revolutionary politics made him not only a difficult subject to capture on film but also a risky commercial gamble for any Hollywood studio hoping to attract substantial crossover audiences and box-office profits.

The fact that such studios backed movies that lost more money than Malcolm X’s eventual $33-million budget, including Anthony Mann’s The Fall of the Roman Empire (1964), Michael Cimino’s Heaven’s Gate (1980), Elaine May’s Ishtar (1987), and Brian De Palma’s The Bonfire of the Vanities (1990), indicates that the studios’ concern with money (Warner Brothers eventually took over the film from Columbia) was not the only, or even primary, reason for taking so long to get Malcolm X into theaters.

Malcolm’s contentious politics—particularly his insistence that anti-Black racism was the province (and product) of a pernicious white supremacy that America could not easily, if ever, overcome and that African Americans were morally obligated to defend themselves against the violence that they suffered at the hands of white people by, if necessary, taking up arms (as guaranteed by the U.S. Constitution)—frightened casual observers schooled in media reports like Mike Wallace’s and Louis Lomax’s 1959 television documentary The Hate That Hate Produced, as well as numerous mainstream newspaper and magazine articles that erroneously portrayed Malcolm as a vehement reverse racist advocating preemptive violence against white Americans.

The reluctance of Hollywood corporations to produce a feature-film adaptation of The Autobiography of Malcolm X, therefore, had as much to do with Malcolm’s bracing, yet incisive analysis of how centuries of white supremacy had inculcated self-hatred in Black Americans as it did with the possibility of the movie not recovering its costs. Many films, after all, lose money at the box office, although fears that Malcolm’s stridency would put off viewers (particularly white viewers) affected studio thinking about Malcolm X’s financial viability.

The difficulties that Lee encountered while directing Malcolm X were well documented at the time because Lee, ever the canny promoter, freely discussed them in press interviews, eventually referring to Warner Brothers as “the Plantation”58 for its refusal to fund the project’s $33-million budget or agree to its epic, three-hour-and-twenty-two-minute length despite offering at least $50 million for Oliver Stone’s three-hour JFK (1991) and, in a decision that Lee rightly protested as an example of the studio’s double standard about funding films by Black directors, $45 million for actor-comedian Dan Aykroyd’s directorial debut, the instantly forgettable Nothing But Trouble (1991). Lee’s companion volume, By Any Means Necessary, adopts Malcolm X’s most famous phrase as its title to recount, through the recollections of key production personnel, the challenges that the film presented its makers.

These issues included Lee’s public skepticism that a white director, whether Sidney Lumet or Norman Jewison (who were both attached to the project at various points), could direct the movie with the necessary political sensitivity or inside knowledge of African American culture; his choice to revise a screenplay originally written by James Baldwin and Arnold Perl rather than use the later screenplays penned by David Bradley, Charles Fuller, David Mamet, and Calder Willingham; and his insistence on travelling to Egypt and Saudi Arabia to shoot Malcolm’s 1964 Mecca trip, as well as to South Africa to film Nelson Mandela for the movie’s final sequence.

Lee also publicly courted African American celebrities Tracy Chapman, Peggy Cooper-Cafritz, Bill Cosby, Janet Jackson, Magic Johnson, Michael Jordan, Prince, and Oprah Winfrey to donate cash to help him complete Malcolm X when the film’s completion-bond company, named Century City California (hired by Warner Brothers to guarantee the film’s budget and to pay all excess costs should the movie go over the $28-million budget cobbled together from Warner Brothers’ $20-million investment and the $8 million paid by Largo Entertainment for Malcolm X’s foreign-distribution rights), halted postproduction while editor Barry Alexander Brown was cutting the film’s extensive footage into a rough assembly because, true to Lee’s predictions, Malcolm X overran its allotted budget (ultimately costing $33 million, the figure that Lee and line producer Jon Kilik had calculated would be necessary to make the film as scripted when first negotiating its budget with Warner Brothers in 1991).59

Lee, indeed, contributed $2 million of his $3-million fee to continue the editing process, then shamed Warner Brothers into rectifying this situation by holding a press conference at the New York Public Library’s Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture on what would have been Malcolm’s sixty-seventh birthday—May 19, 1992—to applaud these celebrity donations as prime examples of Malcolm’s repeated recommendation that African Americans come together to support one another’s creative and commercial ventures.

Lee tells Kaleem Aftab in That’s My Story and I’m Sticking to It that this event had the desired effect, becoming such a negative public-relations spectacle that Warner Brothers began funding the movie the following day.60 Lee’s strategy of openly discussing Malcolm X’s production difficulties generated substantial press coverage that raised the film’s profile before its November 1992 theatrical release, thereby compensating for what Lee considered Warner Brothers’ weak promotional campaign while at the same time maintaining his own notoriety as the most-famous Black director working in American film.

These problems, which threatened to overwhelm the movie itself, constituted only the final leg of Malcolm X’s long production odyssey. Decades-long script difficulties preceded them, as Marvin Worth details in By Any Means Necessary (among other venues), to illustrate the challenges of cinematically adapting not only the Autobiography but also Malcolm’s vituperative attacks on white supremacy, American racism, and the “white devils” that he criticized during NOI rallies.

This ideology, considered radical as well as racist in its day, conflicts with Hollywood’s preference for conservative, comforting, and conformist filmic narratives invested in racial reconciliation rather than honest, complex, and difficult examinations of the economic, political, social, and religious factors that perpetuate, even as they modify, America’s racial animosities. The possibility of making a transformative film about Malcolm’s life, one that respected his revolutionary vision, was enticing enough that James Baldwin (a friend and mutual admirer of Malcolm X) agreed in 1968 to adapt the Autobiography for Columbia Pictures, working on drafts that culminated in a 250-page screenplay rejected by studio executives because, according to David Leeming’s James Baldwin: A Biography, it “read more like a novel than a screenplay.”61

Brian Norman offers the best available scholarly analyses of Baldwin’s aborted attempts at dramatizing Malcolm’s life for the silver screen in the indispensable essays “Reading a ‘Closet Screenplay’: Hollywood, James Baldwin’s Malcolms and the Threat of Historical Irrelevance” and “Bringing Malcolm X to Hollywood,” noting in the former that, after the studio “disliked the effect of Baldwin’s early drafts and forced upon him Arnold Perl as a ‘technical assistant,’” Baldwin began to fear “that his script would be technically cut down to easily digested action scenes. In fact, Baldwin’s former secretary, David Leeming, notes [in the Baldwin biography] that familiar actor-heroes were considered for the role of Malcolm X, even Charlton Heston—‘darkened up a bit.’”62

Baldwin, no stranger to Hollywood’s aesthetic seductions and cultural cachet, which he trenchantly analyzes in the books No Name in the Street (1972) and, especially, The Devil Finds Work (1976), rightly saw these suggestions as presaging a terrible future for Malcolm X. “Anticipating the inevitable,” Norman writes in “Reading a ‘Closet Screenplay,’” Baldwin “hastily published his original version of the script in 1972 as One Day, When I Was Lost, and split town,”63 leaving behind the unproduced “closet screenplay” (subtitled “A Scenario Based on Alex Haley’s The Autobiography of Malcolm X”) that Norman defines as “a print version of a film never realized in the visual medium.”64

The disagreements that prompted Baldwin to leave the project, while familiar (even common) to Hollywood’s committee-driven brand of moviemaking, raise questions about the capacity of any studio film to do justice to Malcolm X’s life and legacy. The most fundamental query, according to Norman, is “Does a blockbuster film inherently fall short of Malcolm’s radical vision?”65

The temptation to answer affirmatively acknowledges the restrictions imposed upon such movies by the commercial aspirations of studio paymasters who, desiring profit over artistic integrity, historical accuracy, and biographical fidelity, remain less interested in the evolving revolutionary activism that Malcolm embraced after leaving NOI—itself a remarkably complex social philosophy that would prove difficult (but not impossible) to dramatize on screen—than in the story of Malcolm’s personal transformation from street hustler to national leader (and, after his death, internationally respected icon).

These constraints are not as problematic as they seem if filmmakers and viewers consider Malcolm’s investiture in radical politics as one (albeit complicated) aspect of his life, although underscoring his individual journey from prison to prominence diverts attention from the institutional, structural, and foundational causes of American racism that Malcolm analyzed (and regularly thrashed) in his public speeches, media appearances, and Autobiography.

Expecting Malcolm X to accomplish so many goals is a fool’s errand, at least as far as Jacquie Jones is concerned in “Spike Lee Presents Malcolm X: The New Black Nationalism,” a contrarian Cineaste essay that discusses the trend of criticizing Malcolm X for not presenting a sufficiently radical portrait of its subject’s life, work, and beliefs (Amiri Baraka, Gerald Horne, William Lyne, and Nell Irvin Painter, among others, all published scholarly pieces around this theme in the twelve months surrounding the movie’s production66).

Jones then states what seems a simple truth about the American movie business: “The charge of Hollywood has never been to produce functional political documents.”67 Jones argues that, while Malcolm X deserves criticism, it is neither a thesis film nor a political treatise. For Jones, commentators like Baraka, Horne, Lyne, and Painter “are suffering from an elemental delusion with regards to Hollywood and its capabilities and some pretty off-base assumptions about contemporary African American popular culture, in which the cinema is the most coveted vehicle,” meaning that, had Lee tried to “capture faithfully the meaning and the resilient spirit of Malcolm in a manner that would satisfy the needs of every person of African descent in the United States, it would have remained as unmade as it has been for the past two decades.”68

Jones defends Lee’s version of Malcolm X as realizing a goal—getting the picture into theaters—that no one else had achieved. She praises the film for accomplishing “something that is rarely done well, and even then most often in fictions like Richard Wright’s Native Son and Toni Morrison’s Beloved: it details the tragic and profound effects of racism on the construction of the African American self-image, and the equally unfortunate repercussions the resulting absence of self-esteem can have on society as a whole.”69

This judgment correctly describes the film’s overall effect, particularly its middle section, when Malcolm endures harsh treatment in prison, where he is quickly nicknamed Satan for his violent and antireligious behavior, only to experience misery while locked in solitary confinement and enlightenment when, after returning to the general population, he encounters a prisoner named Baines (Albert Hall) who converts Malcolm to Islam (and NOI) by stressing the importance of education, self-respect, and discipline.

The prison conversations between Malcolm and Baines develop substance thanks not only to Denzel Washington and Albert Hall’s excellent acting but also to Lee’s narrative patience. Scenes of Malcolm reading in his prison cell long into the night follow scenes of him reading in the prison library until kicked out by guards, while Malcolm’s newfound intellectual discipline finds visual expression in his physical appearance, with Washington transforming the loose-limbed swagger he exhibits during the movie’s first act—set during Malcolm’s days as a Harlem and Roxbury hustler that Lee and cinematographer Ernest Dickerson shoot with the romantic lighting and sweeping camera movements of MGM musicals of the 1940s and 1950s—into a straighter posture and less flamboyant gait that, when combined with the earnest studiousness on Malcolm’s face and his noticeably improved grooming, reflect the inner transformation that he experiences as a result of Baines’s tutelage.

The most effective scene comes when Baines encourages Malcolm, who will eventually copy every word from Webster’s Collegiate Dictionary (beginning with aardvark) into a notebook to improve his penmanship and increase his vocabulary, to compare the definitions of the words black and white. As Baines and Malcolm read these entries aloud, Lee and editor Barry Alexander Brown cut to close-up and panning shots of the words on the page to reinforce their differing registers: black refers to unfavorable concepts such as “enveloped in darkness, hence utterly dismal or gloomy; soiled with dirt; foul; sullen; hostile; forbidding; foully or outrageously wicked; indicating disgrace, dishonor, or culpability” while white refers to progressive ideas such as “free from spot or blemish; innocent; pure; without evil intent; harmless; honest; square-dealing; honorable” and, tellingly, “the opposite of black.”

These images, intercut with Malcolm’s changing facial expression and vocal tone as he realizes just how biased such definitions are, provoke the realization that Baines intends when Malcolm asks him, “This was written by white folks, though, right? This is a white folks’ book?” Malcolm then locates an illustration of Noah Webster in the dictionary’s opening pages to confirm his suspicion.

This scene illustrates Lee’s mastery of narrative compression by cinematically condensing much of the Autobiography’s eleventh chapter, “Saved,” into a longer sequence that illustrates Malcolm’s devotion to his prison education, his newfound passion for reading, and his growing acceptance that, as he states in the book, “the teachings of Mr. Muhammad stressed how history had been ‘whitened’—when white men had written history books, the black man had simply been left out. Mr. Muhammad couldn’t have said anything that would have struck me much harder.”70 Malcolm and Baines’s interlude with the dictionary, in Lisa Kennedy’s opinion, is “an example of Lee’s capacity to capture in a single scene a psycho-socio-racial moment that would require pages of explication.”71

Lee, indeed, adeptly adapts all of the Autobiography’s prison chapters, dramatizing Malcolm’s changing perspective by combining the Autobiography’s pseudonymous “Bimbi” (a fellow black inmate whom Malcolm meets at Charlestown State Prison in 1947 and whom he describes as “the first man I had ever seen command total respect . . . with his words”72) and Malcolm’s siblings Reginald, Philbert, and Hilda (who helped convert him to Islam as practiced by Elijah Muhammad) into the composite character Baines, who guides Malcolm into greater knowledge of his heritage after recognizing the younger man’s fierce intelligence, helping him overcome his drug habit, and preparing him for entry into NOI.

Malcolm X’s dictionary sequence, much to Lee’s credit, gains profound intellectual and emotional power by forcing viewers to consider how fundamental white supremacy is to America’s national history, experience, and character. By depicting Malcolm’s shocked realization that racial prejudice is encoded in the English language, Lee prepares the audience for Malcolm’s later denunciations of how America’s “whitewashed” language, politics, and history create a debilitating self-hatred that destabilizes African American identity and culture.

The Autobiography discusses this theme in nearly every chapter, laying out Malcolm’s case that African American progress, hobbled by the structural racism of American society (and Western culture more broadly conceived), faces appalling institutional constraints that individuals, by themselves, cannot overcome, thereby demanding the collective economic action that leads Elijah Muhammad and Malcolm, following Marcus Garvey’s early-twentieth-century political program, to recommend strict separation between Black and white communities. This Black-nationalist political philosophy caused Malcolm to focus on the conditions of working-class and poor African Americans, whom he inspired in large numbers, while disparaging the “blue-eyed devils” who, in his estimation, passively accepted, when they were not actively aiding, America’s oppressive political, economic, and cultural system.

Malcolm X highlights the idea of white supremacy’s crippling power in the prison sequence before expanding this theme in the film’s third act, when Malcolm rises to become NOI’s top minister by ceaselessly confronting America’s history of slavery and segregation in speeches, lectures, and media appearances that, expertly played by Denzel Washington, convey Malcolm’s combative intelligence, charismatic passion, and raffish charm. Lee’s movie, however, downplays the institutional and structural elements of Malcolm’s social analysis, sidelining Malcolm’s passionate interest in Africa’s anticolonial movements and the tentative acceptance of socialism (as an alternative to capitalism’s inequities) that fascinated Malcolm during his final eighteen months of life, after he leaves NOI, goes on hajj, and begins rethinking many of his previous positions.

The movie becomes a tale of redemption in which Malcolm casts off his beliefs in strict racial separation and the white man’s inherent evil when, during his spiritual transformation in Mecca, Malcolm recognizes the common humanity of all people under Islam. This personal journey holds more interest for Lee than Malcolm’s changing political trajectory, placing Malcolm X firmly within the conventions of the Hollywood biopic. Stressing Malcolm’s personal enlightenment follows the Autobiography’s structure, but dilutes the revolutionary impact of Malcolm’s political philosophy after he departs NOI.

This choice seems to verify David Bradley’s analysis in his illuminating essay “Malcolm’s Mythmaking,” which chronicles Bradley’s efforts to adapt The Autobiography of Malcolm X for producer Marvin Worth and Warner Brothers before Lee joined the project (Bradley, in fact, was one of at least five screenwriters to work on Malcolm X during its twenty-five-year journey to multiplexes).

Bradley argues that, because Malcolm’s life does not easily fit Hollywood’s preferred three-act screenplay structure and because Malcolm refused to adopt the turn-the-other-cheek, integrationist line of other civil-rights leaders, Hollywood studios “didn’t keep firing writers because the scripts were wrong. They kept firing writers because the story was wrong.”73

Malcolm’s life, in other words, exceeds the ability of traditional biopics—with their emphasis on exceptional individuals—to depict his work in the comprehensive detail necessary to dramatizing the radical political positions that made Malcolm a threat to American power structures throughout his adult career.

Avoiding these complications, for viewers invested in radical politics, sells out Malcolm’s legacy by misrepresenting his beliefs, underplaying his activist vision for social change, and reducing his importance as a national leader speaking uncomfortable truths about the fundamental problems ailing the American body politic. The movie, from this perspective, is a failure of vision that emphasizes Malcolm’s legitimate status as an American hero at the expense of his most revolutionary attitudes, thoughts, and arguments.

6. Telling Tales

Lee’s Malcolm X, while not politically timid, nonetheless softens Malcolm’s most searing attacks on white supremacy, his most piercing calls for separatism, and his most radical recommendations for social progress, especially his embrace of pan-Africanism and proto-socialism after travelling in Africa and the Middle East during 1964, where he recognizes that reframing the American civil-rights struggle as an international human-rights liberation movement, along with fundamentally restructuring America’s capitalist economy, is necessary to free Black Americans from the oppression they suffer.

Yet criticizing the film for overlooking this perspective assumes that Malcolm X must include these matters to be a successful depiction of its subject’s life, which raises pressing questions about representation, iconography, and historical memory explored in notable scholarly essays about the movie’s cultural significance, Malcolm and Alex Haley’s construction of identity in The Autobiography of Malcolm X, and the implications of autobiographical narrative’s historical utility.

Malcolm Turvey’s “Black Film Making in the USA: The Case of Malcolm X,” for instance, defends Lee’s movie by noting, in words similar to Jacquie Jones’s Cineaste analysis, that the critical response to Malcolm X, “despite ranging from approbation to condemnation, has been depressingly uniform and univocal in the use of a single strategy or heuristic to interpret the film. ‘How faithful to the true spirit of Malcolm is this film?’ has been the standard question posed by critics and cultural commentators from positions both within and beyond the entire spectrum of institutions,”74 leading Turvey to ask, “For beneath the insistence of this question, its continued and varied return in review after review and commentary after commentary, is there not a single and oppressive demand that Malcolm X be truthful, that it live up to expectations, that it please all those who need and desire Malcolm?”75