How the West Was Lost

Retro Book Review (#1) of Stuart Banner's How the Indians Lost Their Land: Law and Power on the Frontier (2005)

Note to The Vestibule’s subscribers: This entry inaugurates my Retro Book Review series, which will see me post, in chronological order, the academic and mainstream book reviews I’ve published since 2006, the year I became a faculty member in the University of Guam’s Division of English & Applied Linguistics.

And to prime this particular pump, here’s a not-so-brief history of my path into academia. In December 2004, I received my doctoral degree in English and American literature, with specialities in modernism and postmodernism, from Washington University in St. Louis’s Department of English and American Literature (as it was then known—these days, it’s called the Department of English), after which I became a Senior Lecturer.

In other words, I climbed a half-rung on the academic job ladder from meager graduate student to the lowest official post the department offered, essentially a “postdoc” (postdoctoral position) for newly minted Ph.Ds, who were then required, while teaching 100- and 200-level courses for an actual salary ($33,500 if memory serves, a windfall after six years of scrimping and saving my way through graduate school, plus benefits, including Wash U’s excellent health-insurance program), to find permanent academic posts in a job market that, while considered tough at the time, was easy and welcoming compared to the professional killing fields that doctoral students in the humanities face as they search for permanent employment in 2022.

I gave myself two years to land a tenure-track position before returning to Corporate America, that place from which, in 1998, I’d escaped into graduate school after tiring of the rat-race that office work represented, even if I’d enjoyed my time as assistant editor at Towery Publishing in Memphis, TN and as associate editor for Boating World magazine in Atlanta, GA (with a brief, eight-month detour as the only news reporter working on the five-person staff of the Paulding Neighbor—now known as the West Georgia Neighbor—in Paulding County, GA).

I wanted to research; to write; and—in my dream of dreams—to publish essays, reviews, and even fiction, but found myself with little time to do so while writing and editing my way through every weekday. Plus, the life of an independent scholar—meaning a person unaffiliated with an academic institution and, in my case, with only a Bachelor of Arts (B.A.) degree—held little appeal since I knew I wouldn’t be taken seriously unless (and until) I pursued an advanced degree (or two).

Earning Master of Arts (M.A.) and doctoral degrees from Wash U became the first steps to achieving my goals, quaint as they were. Having begun my career straight of out Rhodes College (also in Memphis, TN) as a faculty member at Memphis’s Northside High School, I knew I enjoyed teaching, but I’d grown to love the convivial, back-and-forth conversations that teaching composition, literature, film, and media courses to university students permitted.

So, with two advanced degrees in my hand and hope in my heart, my academic job hunt began. Although I’d started a small consulting business after securing my M.A. degree from Wash U, this work wouldn’t be enough to sustain me unless I began “pounding the pavement,” “cold calling,” and all the other shenanigans that small-business owners must indulge to get their ventures “off the ground.” I disliked the sound of all these business buzzwords, concepts, and phrases—i.e., clichés—in direct proportion to their necessity to making my one-man consulting firm profitable.

In that first year, I mailed paper applications and, for the most technically avant-garde institutions, emailed digital applications to at least 100 colleges and universities across the nation (and across the globe) advertising tenure-track assistant professorships in literature, with a smattering of postdoc opportunities and full-time, non-tenure-track jobs thrown in for good measure.

Although I don’t precisely recall now, I received nine or ten phone interviews that resulted in two invitations to interview in person at 2004’s Modern Language Association Annual Convention, held that year from 27 to 30 December in Philadelphia, PA, where great minds would come together to exchange profound thoughts in bland conference rooms whose decor left much to be desired.

This largest MLA conference is the best-attended gathering of its kind, a place for humanities scholars to present their research, to argue amiably during panel discussions about whatever subjects they find fascinating no matter the announced topic, and to get sozzled in various bars and breweries around town when not interviewing eager Ph.D-holders (like myself) seeking employment in their august palaces of learning, discernment, and refinement.

Such smart people wouldn’t advertise jobs that didn’t exist, would they? An interview, after all, is an interview.

Don’t you believe it.

After my lovely girlfriend, Patricia Thomas, and I purchased plane tickets and booked a hotel room in Philly for the four-day conference, I was informed that both interviews were cancelled because neither tenure-track position had received the necessary funding from its parent university, meaning that neither institution’s hiring team would travel to Pennsylvania or attend the conference in any capacity.

Yes, I should’ve known better. Indeed, I should’ve seen it coming—or whatever other adage you wish to employ to rebuke my naïveté.

The lesson is: Any time a person seeking employment of any kind sees the disclaimer “position contingent upon funding” anywhere in the hiring announcement, that person should assume, as unerringly as night follows day, that no job exists (and, if it does, that this job will disappear before the interview process is complete).

Patricia and I enjoyed four terrific days in Philadelphia despite this setback, but no other job prospects appeared during that academic year. I remained a senior lecturer at Wash U, but couldn’t stay in that job long due to its three-year term limit (new Ph.D-holders are minted on a regular basis, you see).

During that next academic year, 2005-2006, I targeted my search to full-time positions in literature and composition at institutions willing to confirm they had secured funding for said positions. I sent out 70 or 75 applications, from which I received 14 or 15 phone interviews, but no invitations to chat in person at 2005’s MLA convention.

Then, in February 2006, I enjoyed a bright, fun, and collegial phone conversation with four English professors in the University of Guam’s Division of English & Applied Linguistics on a cold winter evening in St. Louis, which happened to be a warm, sunny day on Guam (indeed the next day since, for the uninitiated, the island lies west of the International Date Line).

I was happy to talk with people who asked sharp questions about my research and, especially, the depth of my teaching experience in ways that most other hiring teams hadn’t, making the chance to work with them enticing even if getting a post at a university located on a tropical island felt unlikely and unreal.

Matters were looking grim on the academic-job front as March 2006 rolled into April 2006 when, in April’s second and third weeks, I received email job offers from four different public colleges and universities.

Mind you, I’d only interviewed by phone, but each place (including Stony Brook University on Long Island) told me that its administrators didn’t see the need to pay for campus visits, which in their experience were expensive, hit-or-miss propositions. And in the University of Guam’s case, the hiring budget simply couldn’t afford to spend as much as $2,000 each to fly candidates to the island for personal interviews.

So, with four unexpected (yet welcome!) job offers in hand, I chose UOG, whose compensation package was fair, but, more importantly, proved to be the only one willing to guarantee the opportunity to teach literature courses straight out of the gate. The other three institutions proposed teaching schemes that assigned me four (in one case, five!) composition courses per semester for my first year (or two) as an assistant professor, at which point I could bid to fill unstaffed literature courses (if any such courses went unstaffed).

“Oh, I’m certain that will happen,” I remember thinking to myself, dialing the sarcasm up to ten. Yes, I’d learned my lesson: Without guarantees, no one is required to give you anything not stated in writing.

And since only one contract assured me the chance to teach literature courses as soon as I arrived, alongside the possibility of staffing graduate courses in its newly created M.A. in English program, UOG was an easy choice. The fact that I wouldn’t need to pay a cent to move to a tropical island 8,000 miles from St. Louis didn’t hurt, either.

I relocated to Guåhan (the island’s proper name in the language of its indigenous people, the CHamoru—sometimes printed as “the Chamorro”) in July 2006.

Amid the hurly-burly of buying a car, settling into a new apartment, and teaching four courses at a brand-new job while getting to know my brand-new colleagues, I received, in August 2006, an email message from Dr. Markus Vink (then-associate professor of history at the State University of New York—Fredonia) inviting me to review Stuart Banner’s book How the Indians Lost Their Land: Law and Power on the Frontier (published by Belknap Press, an imprint of Harvard University Press, in late 2005) for Itinerario: Journal of Imperial and Global Interactions.

I’m not certain how Markus tracked me down or why he offered me the opportunity to contribute to his publication (for which he served as book-review editor), but I’m happy he did. Reading and evaluating Banner’s book launched my career as a professional, credentialed, and academically affiliated scholar, becoming the first step in the long road to achieving promotion and tenure at UOG.

Markus, I’m happy to report, remains at SUNY—Fredonia, having been tenured and promoted to professor (or what we insiders, in a happy bit of redundancy, call “full professor”). I’ve remained at UOG, having been tenured and promoted there, so it’s been a good life, all in all. Casting my mind back to those days, weeks, and months makes me wonder how 16 years have passed so quickly (or seem to have passed so quickly), but then I remember that many remarkable events—including living through a pandemic that’s not yet finished—have occurred.

This long preamble serves as an introduction to my entire Retro Book Review series, so, without further ado, here’s my evaluation of How the Indians Lost Their Land. The words, spelling, and punctuation are the same, although I’ve broken some paragraphs into smaller chunks and aligned this review with The Vestibule’s house style (i.e., broken into sections bearing their own subheads; illustrated with images; and linked to notable supplementary materials, websites, and videos).

For people who wish to read How the Indians Lost Their Land and “How the West Was Lost” (my original title, which didn’t appear in Itinerario because the journal doesn’t title its reviews) in their original forms, PDF copies of Banner’s book and my essay are posted near the end of this entry (in a section titled “Files”). Making available full-text copies of my reviews and the books they discuss will become standard features of all Vestibule Retro Reviews (or, I should say, standard whenever such files exist).

—All the best, Jason

How the Indians Lost Their Land:

Law and Power on the Frontier

Written by Stuart Banner

Published by Belknap Press (Imprint of Harvard University Press)

2005

336 pages

ISBN: 0-674-01871-0

$29.95

1. American Land and Its Discontents

The story of Native American land dispossession is a tragedy that haunts the American experience like few other historical events. Only slavery competes with the forcible relocation of American Indians as an injustice so abhorrent that the nation, particularly in times of patriotic fervour, prefers not to acknowledge or even remember. The displacement of Native Americans into areas west of the Mississippi River, culminating in a system of reservations that persists to the present day, is a calamity compounded by the colonial arrogance, ignorance, and racism of European settlers, who proudly claimed that they were taming the wild and savage land that North America represented.

In one of modern scholarship’s profoundest ironies, historians of the American continent, in an effort to better understand the intricacies of the relationship between European immigrants and Native American inhabitants, spent much of the twentieth century coming to terms with the moral, ethical, and spiritual bankruptcy of the nation’s shameful treatment of its indigenous peoples.

Stuart Banner’s admirable new book, How the Indians Lost Their Land: Law and Power on the Frontier, aims to complicate received notions about Indian dispossession. Banner’s goal is not to excuse or to minimize the depressing facts of Native American marginalization, but rather to illuminate the convoluted land policies that led the United States government, often under the banner of improving the Indians’ lot, to remove them from their ancestral homes.

Banner takes an honest approach to his study, declaring in the Introduction that, when asked by a curious student “whether the Indians sold their land or had it taken from them, I responded with the offhand answer I suspect many would give.”1 This reply, Banner fears, may well evade the intricate social, political, and economic congress shared by the Europeans and the Native Americans, a relationship that resists the now tautological claim that the Native Americans’ “different conceptions of property” indicates that “they couldn’t have understood what the settlers meant by sale.”2 Banner, setting an ambitious goal for his book, hopes to soothe the nagging suspicion that he has overlooked the complicated history of Indian-settler relations:

American historiography was once populated by noble settlers and savage Indians; now, more often than not, it is populated by noble Indians and savage settlers. I wondered whether there might be a more intelligible story to be told in which whites disagreed among themselves over whether and how to acquire land, and in which Indians disagreed among themselves over whether and how to sell it.3

Banner succeeds in fulfilling this scholarly project. How the Indians Lost Their Land is a meticulously researched, intelligently argued, and lucidly written book that explores the cultural, economic, and political factors that influenced the initially voluntary, but increasingly forcible exchange of Indian land.

That Banner invests the mind-numbing subject of land policy with intellectual vigour is not only a credit to his talent as a writer, but also a demonstration of his skill as a researcher. The copious information included in the book’s 336 pages does not overwhelm Banner’s argument that the transfer of Native American land to European control was a heady mixture of good intentions, honest trades, fraudulent inducements, outright thievery, and compulsory transactions. This achievement alone qualifies How the Indians Lost Their Land as required reading for history, literature, and cultural-studies courses that examine colonialism and post-colonialism in their American formations.

2. Location, Location, Location

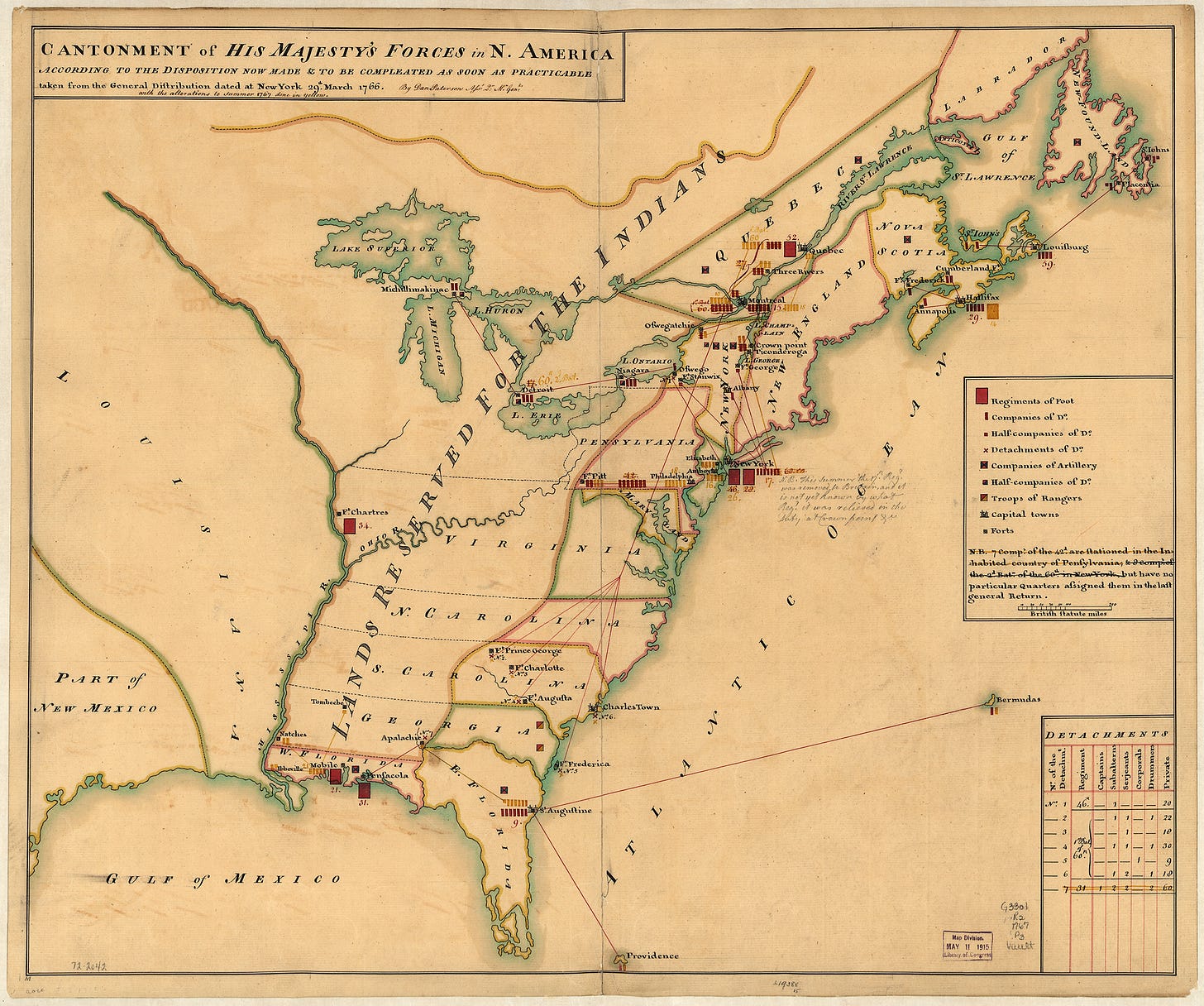

Banner’s thorough analysis of the vagaries of territorial sovereignty during the first two centuries of European settlement is especially enlightening. The book’s first two chapters, “Native Proprietors” and “Manhattan for Twenty-four Dollars,” productively assess how English settlers believed that “the English Crown, by virtue of the English ‘discovery’ and settlement of North America,”4 possessed sovereignty over the entire continent. The Indians maintained rights of self-government, but the land itself was understood to belong to England.

“Most of the charters,” Banner observes in a pregnant passage, “granted property rights as if the charters’ recipients were to be the first human beings in the area.”5 While many accounts of Indian-settler relations end here, Banner probes the historical record more deeply to discover numerous conflicts among the colonial officials, avid settlers, proselytizing clergymen, and commercial traders, who desired, in one way or another, access to Native American land.

Nearly every person, who professed a natural Christian right of conquest over the Indians, according to Banner, was opposed by another person who disputed this notion for religious, ethical, or practical reasons. The convenient theory that Native Americans did not claim property rights, or the even more absurd assertion that the Native Americans did not use the land for productive agricultural purposes, was contradicted by the observations of colonists, who had frequent contact with Indian communities. The picture that emerges is of a colonial society rife with disagreement over the issue of whether to regard the Native Americans as North America’s owners or merely as a people who occupied the land without possessing it.

Banner traces, in laudable detail, how the early English colonial governments came to recognize Indian property rights. Apart from religious conviction, Banner identifies three major reasons for acknowledging Native American land ownership: during the earliest years of colonization, the Native Americans were a larger and more powerful group than the English settlers; the English competed with France for control of North America, recommending a policy of land purchase from Native American inhabitants that would not alienate them or risk pushing Native Americans to ally themselves with the French; and the many English settlers, who had already received titles for land purchased from Native Americans, compelled colonial governments to accept the Native Americans as legitimate owners, lest these transfers be deemed illicit at a later time.

Banner also tackles the legendary story that, in 1626, the Dutch purchased Manhattan in exchange for goods worth twenty-four dollars. His extensive discussion of the relative value of seventeenth-century currencies and their application to land transactions clarifies this issue, while noting that the Native Americans who sold Manhattan did not vacate the land. It supports Banner’s conclusion that these Native Americans may have expected the Dutch to share resources with them rather than claiming exclusive property rights to the area.

Banner’s attention to the differences between European and Indian conceptualizations of property prevents him from stating a definitive conclusion about the fairness of the Manhattan sale, although he observes that European settlers, particularly the English, believed that “they were buying Indian land for a song”6 by the early decades of the eighteenth century.

3. A Banner, Mostly Bang-Up Effort

Rather than engaging in historical generalizations, Banner prefers to highlight the complex motivations and behaviours that drove the fractious, contentious, and ultimately tragic policies that divested Native Americans of their land. This approach has only one drawback, in that a more detailed account of Native American belief systems about the proper role of human beings within the natural order does not underscore the Indian conviction that humanity is the land’s caretaker (or steward), as much as its possessor.

Banner acknowledges this viewpoint, but his insistence that the Indians disagreed among themselves about whether, why, and how to sell land in response to continuing European encroachment occasionally obscures the Indians’ spiritual sense that land is not an object, but rather a subject worthy of profound respect. Banner presents the Native Americans’ metaphysical beliefs about the natural order in his larger argument, but does not stress them as much as he might.

This criticism is not as problematic for Banner’s study as it might sound. He is writing a history of land policy, after all, not anthropology. Banner also imparts the diversity of Native American ideas, attitudes, and beliefs about land ownership with commendable attention to detail.

How the Indians Lost Their Land carefully investigates an issue that has inspired tremendous disagreement, passion, and vitriol among historians of the American continent. The book’s comprehensive treatment of its subject, when coupled with its exhaustive research and articulate prose, should prove invaluable for readers interested in understanding the complex relationship between the Europeans, who regarded themselves as settlers of a new world, and the Native American residents for whom that world was already home.

FILES

NOTES

Stuart Banner, How the Indians Lost Their Land: Law and Power on the Frontier, Belknap Press, 2005, pg. 1.

Banner, How the Indians Lost Their Land: Law and Power on the Frontier, pg. 1.

Banner, How the Indians Lost Their Land: Law and Power on the Frontier, pg. 2.

Banner, How the Indians Lost Their Land: Law and Power on the Frontier, pg. 14.

Banner, How the Indians Lost Their Land: Law and Power on the Frontier, pg. 15.

Banner, How the Indians Lost Their Land: Law and Power on the Frontier, pg. 78.