If You Find This Essay Bad, You Should Read Some of the Others

Why taking Dr. Kirk Johnson's "Towards a More Perfect Union: Teaching and Learning in Micronesia" Seminar was such a rewarding experience.

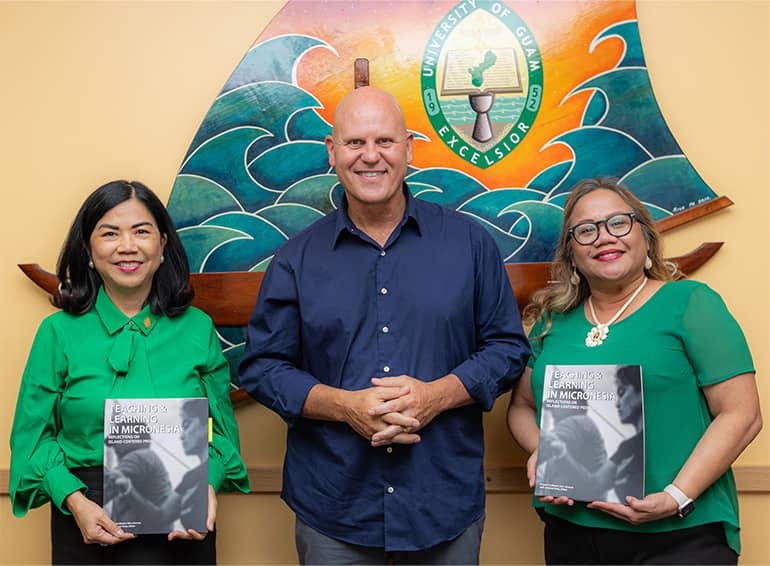

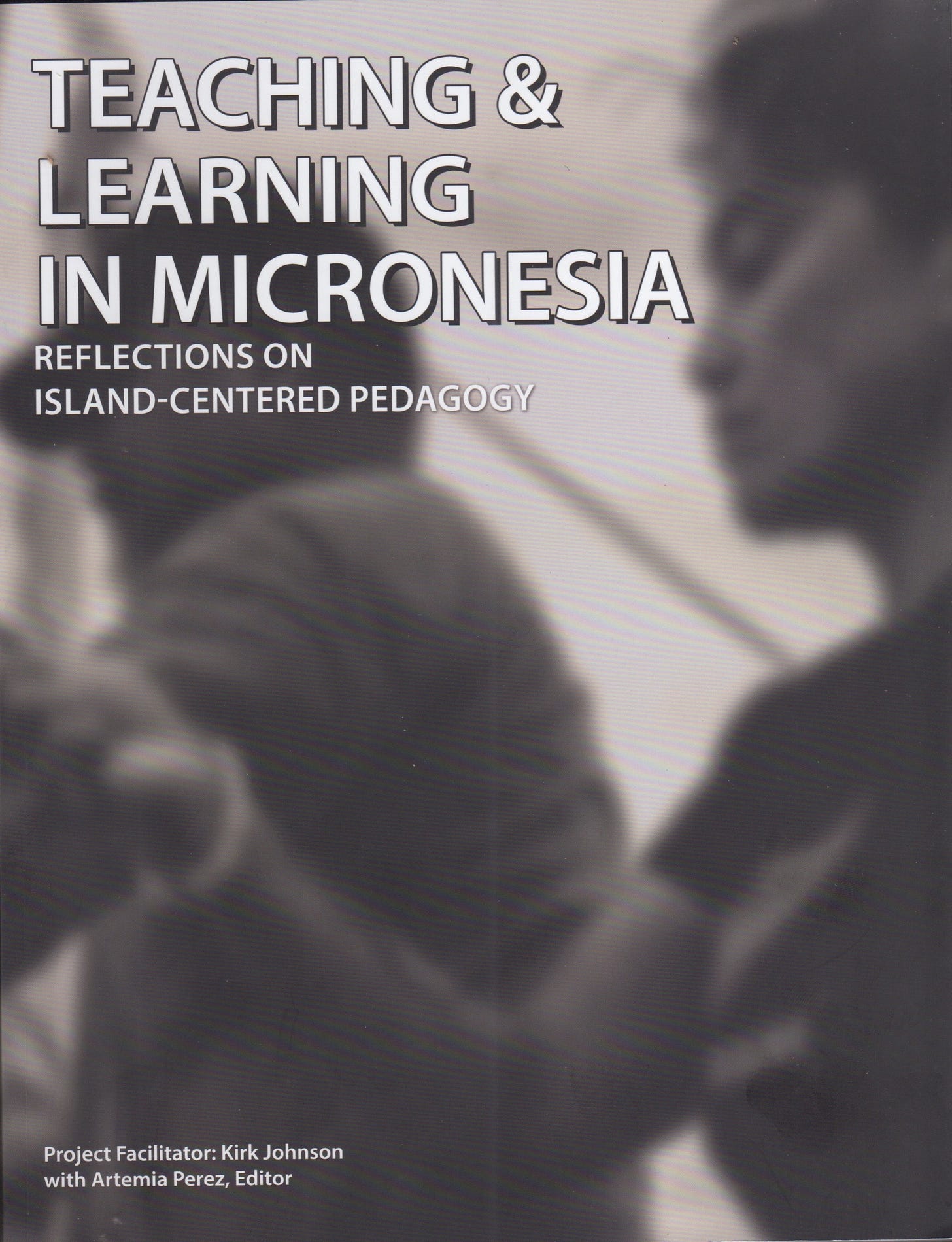

Note to The Vestibule’s subscribers: This post includes my article “If You Find This Essay Bad, You Should Read Some of the Others,” which was recently published in the book Teaching & Learning in Micronesia: Reflections on Island-Centered Pedagogy. This invaluable, 310-page volume is the culmination of two different month-long seminars organized by my colleague and, I’m happy to say, my friend Dr. Kirk Johnson, professor of sociology at my professional home since 2006, the University of Guam.

Kirk, having secured grant funding from the National Endowment for the Humanities, facilitated “Towards a More Perfect Union: Teaching and Learning in Micronesia” twice last year, the first seminar beginning in June 2022 and the second beginning in October 2022. Kirk conducted the June seminar online, while the October seminar was held face-to-face, on UOG’s campus, to bring together faculty members from all levels of Guåhan’s educational system, “new and veteran, young and old, from middle and high school to university level,” as Kirk notes in Teaching & Learning in Micronesia’s introduction.

The seminar’s purpose, Kirk continues, is “to reflect and learn with each other about how we can continue to refine our efforts so that our students engage the learning environment in such a manner that empowers them to build their capacities to be great contributors toward the advancement of Micronesia’s communities.”1

I’m pleased to report that the seminar accomplished all these goals over three Saturday sessions (22 & 29 October and 5 November 2022) that ran from 8am to 1pm, which testifies to how good were the seminar’s reading materials, invited lecturers, and Kirk’s boundless enthusiasm at getting chatty, disputatious, and irascible teachers to arrive punctually during the weekend—hallowed time for all American workers, but particularly sacred to educators escaping the stifling bureaucratic climates of their day jobs—and at how worthwhile, exciting, and all-around-fabulous were the discussions provoked by these readings and lectures.

Teaching & Learning in Micronesia captures the intellectual frisson that typified these conversations better than I could have imagined. Kirk and his co-editor, Artemia Perez, selected this book’s 47 entries from the final essays submitted by every person in both “Towards a More Perfect Union” seminars, papers in which we reflect upon our time together and, in 2,000 to 2,500 words, attempt to offer advice (and even wisdom) to island educators everywhere, whether on Guåhan or—if you’ll forgive this terrible pun—on island Earth.

I’m not certain how useful or wise my piece is, so please offer comments about how good, bad, and/or ugly this article may be. Several fellow participants in the “Towards a More Perfect Union” seminars have mentioned that they chuckled aloud when reading my title, which I always take as a positive sign (even if I shouldn’t jump to conclusions about any reader’s responses).

As such, I can only hope that anyone who finishes the entire piece will laugh alongside my observations and commentaries, although, in truth, I’ll be grateful for any reaction (good, bad, or ugly) just as long as indifference—the death-knell for all work performed in good faith and happy circumstances—doesn’t raise its head.

And “Towards a More Perfect Union” was among the happiest professional circumstances I’ve experienced in many years, so I thank Kirk Johnson and everyone else involved not simply for keeping the faith, but for restoring my faith in the power of people to come together in common cause and then accomplish mutually rewarding ends. If that statement sounds earnest to the point of becoming treacle, it at least has the virtue of being true.

I’ve aligned “If You Find This Essay Bad…” with The Vestibule’s house style by dividing it into sections with their own subheads, inserting relevant images, and offering links to useful supplementary materials. The original piece, along with additional seminar materials, appears in the “Files” section for your perusal and your edification.

All the best—Jason

“If You Find This Essay Bad, You Should Read Some of the Others”

Written by Jason P. Vest

Teaching & Learning in Micronesia: Reflections on Island-Centered Pedagogy

Pages 187-192

Edited by Kirk Johnson & Artemia Perez

2023

1. Canoes & Curricula

My title is a punning reference to American novelist Philip K. Dick’s public lecture “If You Find This World Bad, You Should See Some of the Others,” a September 1977 address that Dick gave at the second annual Festival International de la Science-Fiction in Metz, France. In this speech, Dick (or PKD, as his most ardent admirers call him) tackles subjects as abstruse as eternity, epistemology, ontology, and the possibility that “we collectively dwell in a kind of laser hologram, real creatures in a manufactured quasi-world”2 from the perspective of an author best known during his lifetime (1928-1982) as the hack writer of science-fiction (SF) potboilers.

Yet even by that late date (less than five years before PKD’s untimely 1982 death), his reputation as the visionary author of significant American fiction had begun taking hold despite the aloof regard—if not outright contempt—in which he was held by the literary establishment’s snobbier denizens.

Dick’s title is his humorous rejoinder to people who didn’t take seriously the ideas explored by science fiction (not necessarily, PKD is quick to note, the ideas explored by his own SF novels and short stories, although one cannot escape the sense that, despite his defense of science fiction as a relevant and legitimate form of expression, Dick longs for acceptance by mainstream critics). My essay’s title, to extend this theme, serves as jocular shorthand for how I once thought about the quality of my university courses (meaning the courses I teach), to wit: Even my off days are better than many professors’ good days.

This self-aggrandizing declaration isn’t as narcissistic as it seems given 1) the consistently high ratings I’ve received from students who’ve attended my courses at Washington University in St. Louis, Missouri (my doctoral institution), at Maryville and Webster Universities (also in St. Louis), and at the University of Guam (i.e. UOG, my professional home since August 2006) as well as 2) the fact that, soon after arriving at UOG, I realized that the pedagogical approach I adopted during graduate school was, while suited to UOG’s student population, perhaps not as well suited as I hoped.

In other words, this approach changed, shifted, evolved—choose whatever term seems most progressive, but know that I couldn’t remain the same educator I was before that sunny July 2006 evening when my plane touched down at the Antonio B. Won Pat International Airport on the island of Guåhan.

Teresia K. Teaiwa (1968-2017) makes so many marvelous observations in her essay “The Classroom as Metaphorical Canoe: Co-operative Learning in Pacific Studies” that selecting almost any passage at random yields scholastic chestnuts that any university professor—and, in truth, any teacher who works at any level of just about any educational system—will find useful. Most striking to me are the humility, wonder, and open-hearted curiosity that Teaiwa, an authority on all matters Pacific, manifests throughout her argument, perhaps nowhere better summarized than when she states, about the academic field of Pacific Studies, “the lecturer-student relationship is also one of shared responsibility, as lecturers can never claim omnipotence over this vast region.”3

This notion is one that all teachers, especially university professors high on their reputations as subject-matter experts, should bear in mind while dispensing knowledge to rooms full of eager (and, in some cases, not-so-eager) students. None of us, no matter how much material we have mastered in our chosen field(s) of study and no matter how much time we devote to studying it, can ever fully master it all.

There is simply too much to learn, too much to encounter, too much to experience, and, if we keep our minds and our hearts as open as Teaiwa did during her short life, too much to enjoy about our vocation as educators. Fostering a posture of wonder in the face of what we don’t know seems to me a powerful example to set for all students, with Teaiwa’s canoe metaphor stressing how education, at its best, is a collaborative enterprise that depends upon every person’s active participation.

Philip K. Dick, in his “If You Find This World Bad” lecture, puts the matter this way: “A novelist carries with him constantly what most women carry in large purses: much that is useless, a few absolutely essential items, and then, for good measure, a great number of things that fall in between.”4

So, too, do educators of all stripes no matter our gender, no matter our expertise, and no matter our career stage. Our minds are filing cabinets full of knowledge and information mixed with ephemera and bric-a-brac about topics far and wide that we can, should, and must bring to bear during class sessions covering subjects large, small, significant, tangential, and, for good measure, everything in between. Conveying such knowledge to students in the disciplined and focused, yet fluid manner recommended by Teaiwa’s canoe model remains an ongoing challenge that cooperative learning promotes as much as, if not more than, competitive models do.

2. Frames & Refrains

Several participants in the Teaching and Learning in Micronesia (TALIM) seminar that occasions this essay mentioned acting as facilitators of their students’ learning rather than as pedants arrogantly preaching the gospel of subject-matter proficiency from the altar-lecterns that sit at the head of their classrooms, happily rejecting the example of Thomas Gradgrind, the school-board superintendent who hectors an unlucky captive audience (of students and schoolmasters) in the memorably vituperative opening passage of Charles Dickens’s 1854 novel Hard Times, where Gradgrind extols his own personal utilitarian gospel: “Now, what I want is, Facts. Teach these boys and girls nothing but Facts. Facts alone are wanted in life. Plant nothing else, and root out everything else. . . . In this life, we want nothing but Facts, sir; nothing but Facts!”5

As a humanities scholar and educator, I reject as absurd this unbending ideology even if teaching the differences between fact and opinion, information and misinformation, logic and illogic, and (small-t) truth and untruth remains crucial to our pedagogical mission, to say nothing of an era that sees large-scale lies (medical, social, economic, and political) rampaging across the globe. Even courses in business and the so-called “hard” sciences can (and must) explore the nuances of their subject’s materials even if balance sheets must finally be balanced and experiments must finally yield results. Yet those results are not predetermined, nor should they be, so even if business and science teachers are the people who—to me, at least—seem most likely to adopt Gradgrind’s outlook, such beliefs are erroneous, even prejudicial, given the helpful discussions that TALIM’s weekly sessions evoked.

Michael Karlberg’s essay “Reframing Public Discourses for Peace and Justice,” like Teaiwa’s article, offers powerful observations about the pedagogical stances and missions that teachers at all levels of the American educational system may adopt, but perhaps the most apposite is the following statement: “To insist that the prevailing culture of contest is leading us toward a more peaceful and just social order, or that the culture of contest can be sustained indefinitely as our numbers and impact on this planet continue to grow, is arguably the more naïve and unrealistic expectation.”6

This comment comes midway through Karlberg’s penultimate paragraph, helping to accomplish the goal that he sets at the outset, namely altering his readers’ perceptions about the stifling rhetoric of neoliberal competition that suffuses popular and, to a lesser extent, academic debates about how to seek greater understanding, inclusivity, and justice in a world that seems less committed to these ideas (and ideals) with every passing day.

Acknowledging this reality—a term that frequently arises in Karlberg’s essay, in the conversations that characterized the TALIM Seminar, and in the fictional Thomas Gradgrind’s lexicon of “just the facts”—makes Karlberg’s recommendations far more palatable. Many of the public-school teachers in the TALIM small-discussion group that I joined after Karlberg addressed us by video conference praised his writing, but, in the next breath, asked how his theoretical concerns apply to the hurly-burly of actual classroom practice.

These educators, they were quick to note, must expend tremendous energy just getting their students to pay attention before they can teach lessons about the curricular subjects they are required to cover. “How can I translate this into my daily life of working with students of varied aptitude and preparation, some who may not even have eaten breakfast?” asked one social-studies teacher (from Guåhan’s George Washington High School) about Karlberg’s sometimes abstruse analyses of global events. “How,” she prodded, “can we make this real for ourselves and our students?”

This incisive question, asked almost off-the-cuff during an enjoyable back-and-forth among five public high-school teachers plus myself, reminded me of those long-ago days during the 1990s when I too taught high school, days where making theories, notions, and ideas propounded by educational experts real to students struggling with the daily conflicts, deficiencies, and problems created by the “culture of contest” that Karlberg’s essay so acutely skewers seemed fantastical, even farcical—to the point that doing so resembled the travails of ancient ocean voyagers, already uncertain if their destination exists at all, sighting land across the horizon, only to discover, upon approaching the shoreline, that only a mirage awaits them.

Karlberg reframes our understanding of the term reality by writing in his conclusion, “Our reproductive and technological successes as a species have transformed the conditions of our own existence. This new reality requires us to adopt a new realism—one that recognizes our organic interdependence and seeks to translate this recognition into a more peaceful, just, and sustainable social order.”7 The term new realism has many valences, one of which is to remind professional educators that transformation is an active process, something that human beings intentionally pursue, meaning that, as teachers, we can adopt similarly intentional and active pedagogical methods to bring change to our students’ understanding (and, perhaps, to their lives, as well).

Change does not necessarily mean the wholesale reframing of the many different discourses that surround our students, but it can mean helping them to understand the conceptual frameworks that they inhabit, which then allows us to demonstrate, in small ways throughout an entire semester, how to alter those frames step by step and piece by piece.

3. Resistance & Reality

This pursuit seems a critical component for any diligent educator working in the 21st Century to adopt. My small-group colleagues mentioned specific strategies based on local wisdom (that they have gleaned from their families and from growing up on Guåhan) that they bring to their classrooms, yet most of them had rarely conceptualized transferring these practices to their students as reframing their students’ discourse—even if that goal is precisely what they accomplish. These teachers, in other words, synthesize local wisdom with the Western-influenced pedagogical requirements foisted upon them by the Guam Department of Education’s bureaucracy to fashion a hybrid educational experience for their students.

Apart from once again demonstrating how privileged university professors are in our pedagogical pursuits (especially the “classroom management” problems that we—or, certainly, that I—rarely if ever encounter), this conversation also reminded me of two books important to my own pedagogical practice: Linda Tuhiwai Smith’s Decolonizing Methodologies: Research and Indigenous Peoples and Ngũgĩ wa Thiong’o’s Decolonising the Mind: The Politics of Language in African Literature.

Both texts examine numerous ways to reframe educational discourses for the benefit of students matriculating through educational systems set up by colonial bureaucracies throughout Oceania and Africa that can help teachers all over the world recognize the hierarchical assumptions undergirding the complex systems of power, regulation, and control that envelop us all. Karlberg discusses similar notions when criticizing what he calls “the culture of contest,” whereas Tuhiwai Smith and wa Thiong’o in their books employ the metaphor of the ladder to point out how hierarchical systems presume that people inhabiting the top rungs are better, smarter, and worthier than those people residing on the lower rungs, plebes assumed to be less deserving of (and less receptive to) the privileges that those same top-rung holders presume to mete out to their subordinates through insulting displays of noblesse oblige.

We can, therefore, profit from considering Tuhiwai Smith’s declaration in Decolonizing Methodologies’ second-edition introduction that, when her book’s first edition was published in 1999, “indigenous communities were most often the objects or subjects of study by non-indigenous researchers. They were not considered agents of themselves, as capable of or interested in research or as having expert knowledge about themselves and their conditions”8 and of wa Thiong’o’s observation in Decolonising the Mind’s first chapter that, when dealing with African literature and culture, “Language as communication has three aspects or elements. There is first what Karl Marx once called the language of real life,” “the second aspect . . . is speech and it imitates the language of real life, that is communication in production,” and “the third aspect is the written signs. The written word imitates the spoken.”9

The presumption that orality—what we might call, after Marx and wa Thiong’o, the language of real life—is primitive compared to written language is false, indeed a remnant of the hierarchical colonial systems whose structures still influence the educational bureaucracies in which so many educators work. Reframing discourse is a way of reshaping language and, consequently, a way of reshaping the reality we experience inside and outside the classroom. Bringing even small bits of these perspectives to our pedagogical practices qualifies, at least in my view, as an act of resistance against said bureaucracies that can assist our students in recognizing not only their own place within these systems but also their power to revise, even incrementally, said systems.

These thoughts inevitably bring me to the late-great American novelist Ursula K. Le Guin, who, during her fabulous 19 November 2014 speech accepting the National Book Foundation’s Medal for Distinguished Contribution to American Letters, offered so many pearls of wisdom for professional educators of all kinds to consider that this brief talk might well have been designed for that purpose.

It wasn’t, but Le Guin’s address that night has become a legendary statement of principles about the necessity of literary art (and, especially, the significance of science fiction and fantasy fiction) to keeping alive the possibilities of positive change in the complex, difficult, and demanding world we all collectively inhabit: “I think hard times are coming when we will be wanting the voices of writers who can see alternatives to how we live now and can see through our fear-stricken society and its obsessive technologies to other ways of being, and even imagine some real grounds for hope. We will need writers who can remember freedom: poets, visionaries, the realists of a larger reality.”10

These realists of a larger reality (a marvelous phrase!) are precisely the people who put into practice the new realism that Teaiwa, Karlberg, Tuhiwai Smith, and wa Thiong’o explore in their own work. These new realists include professional educators who, by helping create Le Guin’s larger reality—in drips, in drabs, and in short strides taken while surviving the strenuous schedules that we all must keep—can decolonize our courses and our minds, even if achieving such grand outcomes does not and cannot outweigh the more modest goals of getting through the day, the week, the quarter, the semester, and the syllabus with our wits intact.

As challenging as the quotidian labor of education can be, Le Guin’s perspective helps us—or, at least, helps me—understand how vibrantly vital a mission it is. We should avoid becoming too precious and too pompous about our public images as educators—let us take our work seriously but ourselves far less so—while striving to help students navigate the complicated currents they encounter regularly, even ceaselessly, while spending part of their lives with us. As our understanding grows, so shall theirs.

Here endeth the lesson.

FILES

NOTES

Kirk Johnson, Ph.D., “Introduction, Overview, and Framework,” Teaching & Learning in Micronesia: Reflections on Island-Centered Pedagogy, edited by Kirk Johnson & Artemia Perez, University of Guam, 2023.

Philip K. Dick, “If You Find This World Bad, You Should See Some of the Others,” The Shifting Realities of Philip K. Dick: Selected Literary and Philosophical Writings, edited by Lawrence Sutin, Vintage Books, 1995, pg. 253.

Teresia K. Teaiwa, “The Classroom as Metaphorical Canoe: Co-operative Learning in Pacific Studies,” WINHEC: International Journal of Indigenous Education Scholarship, no. 1, 2005, pg. 8.

Teaiwa’s article appears in manuscript form, so, despite the official bibliographic entry given above, the essay from which I quote Teaiwa’s words appears on pages numbered 1 through 17. All citations refer to these manuscript page numbers, not to the bibliographic entry’s pages.

Dick, “If You Find This World Bad, You Should See Some of the Others,” pg. 233.

Charles Dickens, Hard Times: For These Times, first published 1854, Penguin Classics, 1969, pg. 47.

Michael Karlberg, “Reframing Public Discourses for Peace and Justice,” Forming a Culture of Peace: Reframing Narratives of Intergroup Relations, Equity, and Justice, edited by Karina Korostelina, Palgrave Macmillan, 2012, pg. 32.

Ibid.

Linda Tuhiwai Smith, Decolonizing Methodologies: Research and Indigenous Peoples, first published in 1999, 2nd edition, Zed Books, 2012, pg. x. The emphasis is mine.

Ngũgĩ wa Thiong’o, Decolonising the Mind: The Politics of Language in African Literature, Heinemann Books, 1986, pp. 14-15. The emphasis is mine.

Ursula K. Le Guin, “Ursula’s Acceptance Speech: Medal for Distinguished Contribution to American Letters,” 19 November 2014, UrsulaKLeGuin.com, https://www.ursulakleguin.com/nbf-medal. The emphasis is mine.

Jason,

As always, I enjoyed your writing as your mind meanders through the various subjects it touches. Humor laced with doses of reality and quotes from some great thinkers made this article insightful and fun to read. Keep the essays coming.

Lewis