Note to The Vestibule’s subscribers (11 February 2025): Late last year, while enjoying my annual holiday respite from university teaching, I received, in December 2024’s final week, a message from a correspondent I hadn’t previously known requesting copies of an article, first published on 1 September 2010, that addressed the then-hot topic of American television’s “New Golden Age,” as so many people—critics, reviewers, scholars, and everyday folk—were discussing, in person and online, during those halcyon days.

Yes, 14 years had passed since I’d prepared this essay for the publishing behemoth ABC-CLIO’s online Enduring Questions Database, a project into which I’d been enlisted by two Greenwood Publishing Group editors named George Butler and Rebecca Matheson, who asked me to choose one question from a long list of 50-plus queries they’d compiled, then prepare a punchy article about this topic.

George and Rebecca had conceived the Enduring Questions project as a forum where intelligent readers—meaning people not necessarily grounded in the critical theories then (and now) dotting the academic landscape, but who were quick studies nonetheless—could encounter learned essays about relevant cultural questions that omitted the ornate jargon, dense sentences, and impenetrable prose that, they felt, characterized too much academic writing, especially scholarship in the humanities.

In other words, Rebecca remarked while probing my interest in contributing to the Enduring Questions project, let’s be rigorous, yet accessible in our work. This pithy declaration suggested that any Enduring Questions author should write scholarship that people might actually enjoy reading (gasp!) rather than adopting the elitist tone that characterized just enough specialist fare—again, particularly in the humanities—to make its audience members grind their collective teeth in frustration, if not anger.

This invitation proved irresistible to me, a person who’d railed against bad scholarly writing even before I began, in August 1998, graduate study in Washington University in St. Louis’s Department of English & American Literature (now the Department of English). I was, in Summer 2010, a newly promoted—yet still untenured—associate professor in the University of Guam’s Division of English & Applied Linguistics whose resistance to the leaden, even somnambulistic prose encountered in professional journals had only stiffened in the years since I’d received my doctorate. I’m sorry to say that my dissertation, about Philip K. Dick’s visionary fiction, was full of such writing, so I now take the opportunity to apologize to every member of my dissertation committee for inflicting such dross upon them.

Even so, I’d begun living the life of a gainfully employed scholar interested in literature, in culture, in literary culture, and in popular culture—something I hadn’t dreamed possible while in graduate school. Yet here I was, teaching undergraduate and graduate students while publishing journal articles and, in 2007 (in hardback) and again in 2009 (in paperback), Future Imperfect: Philip K. Dick at the Movies, the first of four scholarly monographs I’d author, with the second (The Postmodern Humanism of Philip K. Dick) appearing in early 2009 and the third (“The Wire,” “Deadwood,” “Homicide,” and “NYPD Blue”: Violence Is Power) appearing in Summer 2010.

I don’t recall reading much past the question “Was There Ever a Golden Age of Television?” before saying “Yes!” to George’s and Rebecca’s request. Then began a happy period of reading, watching, and thinking about American television’s development as an artistic and commercial medium, even if some people didn’t acknowledge the art part.

After receiving suggestions from three peer reviewers and then revising my draft to George’s and Rebecca’s satisfaction, this piece was published in the Enduring Questions Database on 1 September 2010. Yet that database no longer exists, at least in the same form that it did 15 years ago. Although I thought I’d received offprints of “Out of the Twilight Zone: American Television Comes of Age” (my article’s eventual title) from Rebecca (and, moreover, thought I’d taken screenshots of this essay’s digital version), I couldn’t find them anywhere last December.

And I still can’t find them, although I’ve looked here and there, in the real and online worlds. I’ll continue sleuthing around my campus office, my home office, and ABC-CLIO’s website for the published piece, but I recently realized that my final-draft manuscript may be all that’s left.

As such, I now present to you “Out of the Twilight Zone: American Television Comes of Age,” the first of my three contributions to the Enduring Questions Database. I’ve aligned it with The Vestibule’s house style while revising certain passages for clarity, yet resisted the temptation to include television programs broadcast since this piece’s original (2010) publication. As such, reading it evokes the sensation of traveling backward in time one-and-a-half decades, so I hope taking this journey is as fun for you as it has been for me.

Please note that the Enduring Questions format (replicated here) includes six units: 1) the Question, 2) a Quick Response, 3) the Essay, 4) the Works Cited section, 5) the Further Reading section, and 6) the Endnotes section.

You’ll also find in the Files section digital versions of some, but not all, articles and books mentioned below.

All the best—Jason

Addendum to Introductory Note (17 February 2025): While methodically searching my campus office for a copy of this essay, I found one in a folder lodged on the floor of my filing cabinet’s bottom drawer, buried under the many other folders hanging there, as if someone (who could it be?) shoved the original folder there rather than hanging it in the correct, upright position. Indeed, I found two different copies: one printed from the Enduring Questions Database specifically formatted for the page (marked “Print”) and one as it appeared while reading the article onscreen (marked “Web”).

Both now appear in the “Files” section below.

All the best—Jason

Enduring Question

Was There Ever a Golden Age of Television?

Quick Response

The only honest answer to this question is “perhaps” because, no matter how final it sounds, the term Golden Age poses unique problems for cultural observers.

1. Golden Ages

The numerous golden ages that art historians, musicologists, theatrical scholars, literary critics, and media theorists extol in their writing are, to recall George Steiner’s memorable comment about the unending literary analyses of Franz Kafka’s novel The Trial, “cancerous.”1 References to golden ages multiply so quickly in academic and popular discourse that even diligent readers can’t track them all, much less fathom the maddening vagueness (and peerless narcissism) of identifying an era and its works as unswervingly marvelous. Proclaiming Periclean Athens an historical golden age, the period encompassing Bach’s cantatas and Beethoven’s symphonies a musical golden age, Elizabethan drama a theatrical golden age, and the Victorian novel’s prominence a literary golden age enshrines these periods, art forms, genres, and modes as indispensable contributions to human culture.

Golden ages, therefore, depend upon elitist, hierarchical, and exclusionary judgments. According to their proponents’ misty-eyed proclamations, golden ages embody human genius in ways so sublime that their reputations become unassailable. Doubting the reality of golden ages—whether art, architecture, brewing, cinema, comics, dance, drama, fashion, gaming, government, history, journalism, literature, music, sports, even needlepoint (this list could indefinitely continue)—mistrusts humanity’s nobility of purpose, capacity for greatness, and record of achievement. Only the most callous, jaded, or dyspeptic thinker would suggest that the term Golden Age, as a concept, remains an enabling fiction that cloaks subjective historical, artistic, and literary preferences in the mantle of objective truth.

To discuss the Golden Age(s) of American television, therefore, may seem oxymoronic. Robert J. Thompson, in the opening pages of his 1996 book Television’s Second Golden Age: From “Hill Street Blues” to “ER,” smartly describes this conundrum: “That Americans took early to calling the television set the boob tube and the idiot box says a lot about what they thought of what came out of it. The publicly voiced opinion of many thinking adults still holds that entertainment TV in general is usually at best a waste of time and at worst a toxic influence.”2 Television, to follow this line of argument, doesn’t edify its viewer, being neither good nor good for its audience, but instead offers mindless escapism to counter the hard realities of daily life. Television, in Todd Gitlin’s formulation, is “entertainer, painkiller, vast wasteland, companion to the lonely, white noise, thief of time,”3 or, in simpler language, a guilty pleasure that rarely (if ever) produces thoughtful art.

Persistent talk about the Golden Age of Television, however, defies Gitlin’s dismissive stance. Thompson defines this nostalgic idea in his book’s preface: “Ask anyone over fifty and they’re likely to tell you that they just don’t make television like they used to. Their eyes may glaze over as they recall the ‘Golden Age of Television’—a time stretching roughly from 1947 to 1960 when serious people could take TV seriously.”4 This notion—that television, like most features of American life, was better during the mid-20th Century—naïvely recalls a simpler, more conservative, and more comprehensible era where few people locked their doors; housewives gratefully stayed home; children played in large backyards; and filmed entertainment was elegant, decent, and refined.

This portrait of the American 1950s is a lie that disregards the political, social, economic, and cultural foment that characterized that decade. No one who seriously studies the Fifties, as David Halberstam attests in his 1993 book The Fifties, can escape the era’s complex combustibility, particularly when discussing its popular arts. Cinema, comics, photography, radio, and television chronicled a time of remarkable upheaval: the Civil Rights Movement, the Cold War, Europe’s postwar reconstruction, Africa’s early decolonization, Senator Joseph McCarthy’s anti-Communist ramblings, America’s military involvement in Korea, school desegregation, Fredric Wertham’s crusade against comic-book violence, the interstate-highway system’s construction, rapid suburbanization, and the expanding national-security state all contended for attention in the minds of busy Americans.

The staid reputation of mid-century America as a Golden Age preceding the 1960s’ angry activism, however, largely persists because televised comedies like The Adventures of Ozzie and Harriet (1952-1966), Leave It to Beaver (1957-1963), and The Donna Reed Show (1958-1966) depict the 1950s as a peaceful, even idyllic time in which the memories of World War II, the savageries of segregation, and the fears of nuclear annihilation rarely trouble the middle-class, white-picket-fence communities that remain the dominant image of Fifties America. Halberstam straightforwardly summarizes this sanitized representation: “By the mid-fifties television portrayed a wonderfully antiseptic world of idealized homes in an idealized, unflawed America. There were no economic crises, no class divisions or resentments, no ethnic tensions, few if any hyphenated Americans, few if any minority characters.”5 Television’s capacity to elevate America’s mid-century prosperity into near-utopia reciprocally cements the medium’s own standing as the purveyor of worthwhile entertainment that comforts its viewer by erasing everyday tensions, anxieties, and conflicts.

2. Golden Memories

American television’s first Golden Age, therefore, wasn’t as splendid as its later reputation suggests. Thompson acknowledges this truth by writing, “the TV of the 1950s continues to bask in the glow of selective recall. Most living Americans have no memory of what TV was really like back then, and only the good stuff is ever seen in reruns and in montage sequences on Emmy Award shows and network anniversary specials.”6 Fond recollections of comedy-variety programs like Milton Berle’s Texaco Star Theater (1948-1956) and Sid Caesar’s Your Show of Shows (1950-1954), along with happy memories of theatrical anthologies like Studio One (1948-1958) and Playhouse 90 (1956-1961), burnish the decade’s image as a time of mature small-screen content.

The major networks’ primetime programming schedules, however, contained much mediocre (and even laughable) fare. Marc Scott Zicree’s 1982 book The Twilight Zone Companion substantiates this claim by reprinting the Cincinnati Times-Star’s 12 November 1953 television guide to demonstrate that Rod Serling—six years before creating and producing one of the medium’s most innovative series, The Twilight Zone (1959-1964)—faced little competition as a serious dramatist. The program listings under the category Drama, cited by time and channel, offer compelling proof:

6:30 12—Superman’s secret identity is threatened by a gangster’s dog.

7:00 9—Captain Video advises Rangers to blast at full space speed.

7:30 9—Tom Conway stars as Inspector Mark Saber.

8:00 5—Joan complicates Brad’s hobby of collecting tropical fish.

8:30 9—Colonel Flack outswindles a tout at the racetrack.

8:30 5—“My Little Margie” causes “A Slight Misunderstanding” worth $35,000.

9:00 5—Cincinnatian Rod Serling’s “A Long Time Till Dawn”, story of tumultuous conflict in a young poet, is produced.7

That James Dean played this troubled poet further highlights the gap between Serling’s effort and its competitors. When Zicree comments, “Given this kind of comparison, it’s easy to see why young Serling, only twenty-eight in 1953, quickly gained the notice of both the public and a number of television critics,”8 the Golden Age of Television (these capital letters signaling its unchallenged significance) loses luster. No matter how good some programs were, others were dreadful.

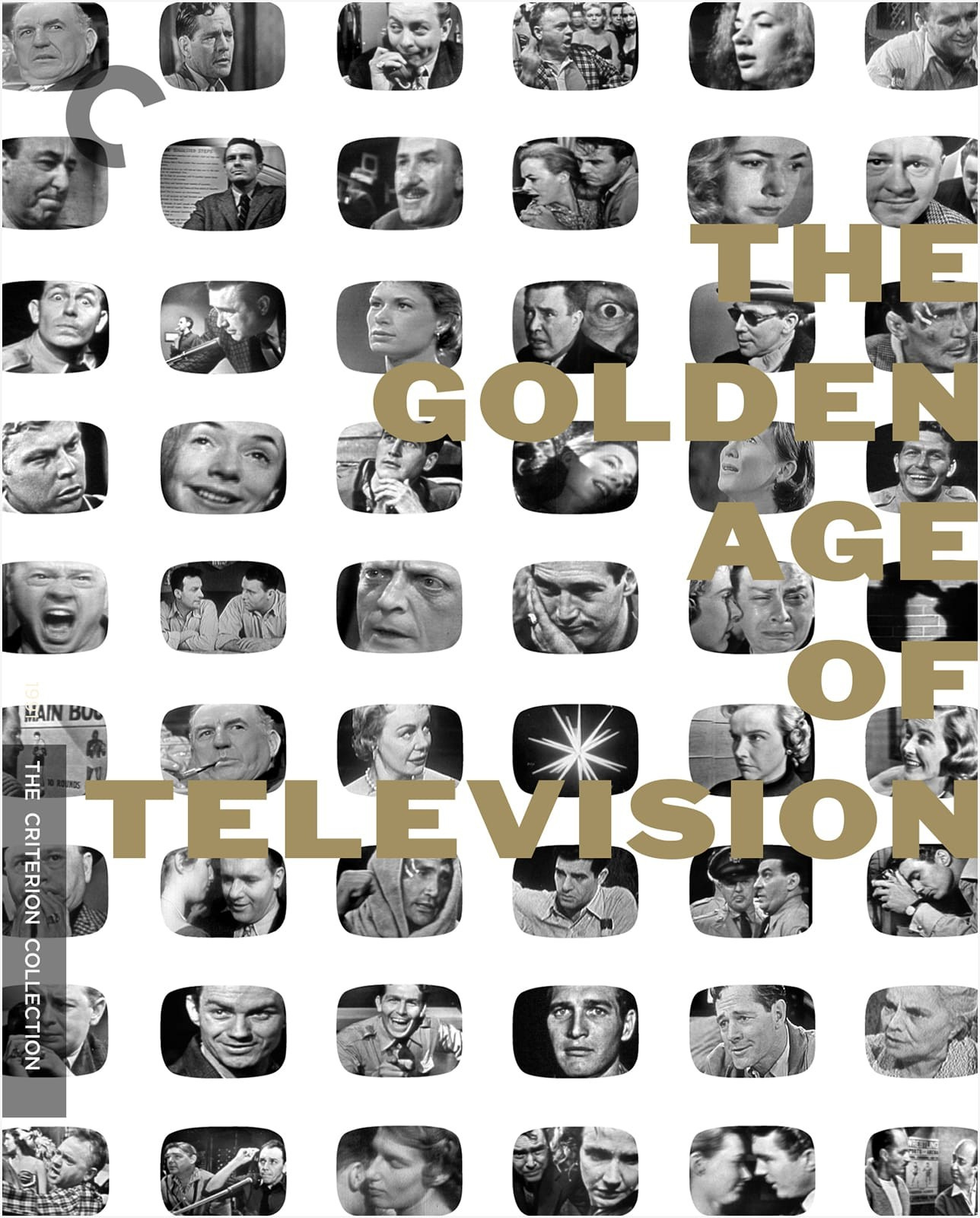

The title of Thompson’s book, however, suggests that American television experienced at least two distinctly artful periods. If 1947-1960 constitutes television’s First Golden Age, then the era inaugurated by Hill Street Blues’s 15 January 1981 premiere begins what David Bianculli, in his 1992 book Teleliteracy: Taking Television Seriously, calls the “Platinum Age of Television.”9 Bianculli’s appellation not only compounds the definitional problems associated with the term Golden Age, but also indicates the growing perception among critics, scholars, and regular viewers that American television had achieved a sophistication rarely seen in earlier times (including the much-vaunted First Golden Age).

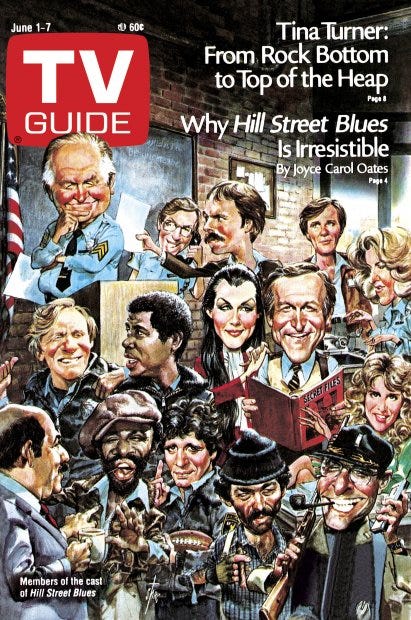

Hill Street Blues challenged its audience’s expectations of primetime drama by serializing storylines over multiple episodes. Grafting one of the soap opera’s fundamental narrative conventions onto the cop show’s urban adventurism allowed creators Steven Bochco and Michael Kozoll to develop characters, themes, and settings so precisely that Joyce Carol Oates, in TV Guide’s 1-7 June 1985 cover article, claims that Hill Street “is one of the few television programs watched by a fair percentage of my Princeton colleagues arguably because it is one of the few current television programs that is as intellectually and emotionally provocative as a good book. In fact, from the very first, Hill Street Blues struck me as Dickensian in its superb character studies, its energy, its variety; above all, its audacity.”10 These words, written by a celebrated American novelist, praise Bochco’s and Kozoll’s series while indirectly christening American television’s Second Golden Age as the province of novelistic narratives that actively subvert televisual conventions.

Oates ignores the debt that Hill Street owes to perhaps the most bastardized television genre of all—the daytime soap opera—to announce the arrival of a thoughtful, artistic, and valuable weekly series that emerges out of the “vast wasteland” that “Television and the Public Interest,” FCC Chairman Newton N. Minow’s 9 May 1961 address to the National Association of Broadcasters, famously (and infamously) identified.11 Oates, like other mainstream and academic writers, downplays Hill Street’s televisual precursors to place the program in an august literary lineage that stretches back to the Victorian Age’s most famous novelist.

This tendency had become a tradition by 1995, when New York Times Book Review editor Charles McGrath, in an article titled “The Triumph of the Prime-Time Novel,” states, “TV is actually enjoying a sort of golden age—it has become a medium you can consistently rely on not just for distraction but for enlightenment.”12 This declaration precedes a sober analysis of Law & Order (1990-2010, 2022-Present), Picket Fences (1992-1996), Homicide: Life on the Street (1993-1999), NYPD Blue (1993-2005), Chicago Hope (1994-2000), and ER (1994-2009) as valuable contributions to American culture. McGrath goes even further by identifying primetime television drama as “one of the few remaining art forms to continue the tradition of classic American realism, the realism of Dreiser and Hopper: the painstaking, almost literal examination of middle- and working-class lives in the conviction that truth resides less in ideas than in details closely observed. More than many novels, TV tells us how we live today.”13

When the editor of the Times Book Review—a person dedicated to assessing the quality of printed literature for America’s most prominent readership—employs the term Golden Age to describe primetime American television as a realistic medium, no concerns about that term’s utility can long survive. Robert J. Thompson’s book, released one year after McGrath’s article, capitalized on a growing trend—influenced by academic treatises, popular-press debates, and watercooler discussions—that television had passed an important threshold to become a serious, significant, and insightful medium.

Even so, the above provisos, doubts, and suspicions can’t belie the sense that, during the 1980s, American television left its adolescence to develop more adult, complex, and relevant storytelling. Such cautions also fail to hide the habit of the medium’s most passionate advocates to proclaim their present moment as the true Golden Age of Television. For example, the decade of the 1950s—with its theatrical anthologies, Alfred Hitchcock Presents (1955-1962), Naked City (1958-1963), and The Twilight Zone—first laid claim to provocative programming.

The 1960s, producing even more series for viewers to watch, saw The Defenders (1961-1965), East Side/West Side (1963-1964), The Outer Limits (1963-1965), The Fugitive (1963-1967), Star Trek (1966-1969), The Smothers Brothers Comedy Hour (1967-1969), Mission: Impossible (1966-1973), and Julia (1968-1971)—among others—expand the narrative conventions, parameters, and intricacy of televised comedy and drama. The 1970s saw situation comedies bloom into significant venues for social criticism, satire, and parody, with the later seasons of The Carol Burnett Show (1967-1978), The Mary Tyler Moore Show (1970-1977), All in the Family (1971-1979), The Bob Newhart Show (1972-1978), M*A*S*H (1972-1983), Good Times (1974-1979), and Taxi (1978-1983) blending topical storylines (or comedy sketches) with biting humor, while, in the same decade, Columbo (1971-1978 & 1989-2003), Kojak (1973-1978), Kolchak: The Night Stalker (1974-1975), and The Incredible Hulk (1977-1982) refreshed the detective, cop, newspaper, and comic-book genres.

The 1980s made adult storytelling a requirement of its best dramas and comedies by seeing Hill Street Blues (1981-1987), Cagney & Lacey (1981-1988), St. Elsewhere (1982-1988), Cheers (1982-1993), The Equalizer (1985-1989), Moonlighting (1985-1989), Frank’s Place (1987-1988), Wiseguy (1987-1990), Star Trek: The Next Generation (1987-1994), China Beach (1988-1991), and Quantum Leap (1989-1993) achieve critical and popular success after arriving on network schedules or in first-run syndication (with The Next Generation establishing an alternative business model to the network and cable outlets that, by the decade’s conclusion, were available in many American homes). Thompson argues that Dallas (1978-1991) “gave memory to the entire medium”14 to establish the multi-episode story arc as a narrative convention that allowed primetime television to replicate more closely the literary effects of good novels.

The 1990s, therefore, so handsomely benefited from these developments that this decade produced television drama and comedy that regularly challenged, confronted, enlightened, and mystified its audience, with Twin Peaks (1990-1991 & 2017), Oz (1997-2003), and The Sopranos (1999-2007) encompassing the 1990s’ provocative programming. Law & Order began in 1990 (with its first spinoff series, Law & Order: Special Victims Unit, debuting in 1999), while January 1993 saw two complicated, intricate, and insightful series—Star Trek: Deep Space Nine (1993-1999) and the aforementioned Homicide: Life on the Street—premiere.

The Adventures of Brisco County Jr. (1993-1994), NYPD Blue (1993-2005), and The X-Files (1993-2002, 2016, & 2018) also arrived in 1993 to offer innovative approaches to old genres. Millennium (1996-1999)—thanks to sharp writing and Lance Henriksen’s masterful performance as criminal profiler Frank Black—profoundly explored the origins of human violence, spirituality, and religion, while Frasier (1993-2004) combined sophisticated dialogue with family melodrama to produce a superlatively acted sitcom. The West Wing (1999-2006) made national politics appointment drama even as the short-lived American Gothic (1995-1996) and Nowhere Man (1995-1996)—like The X-Files and Millennium—offered wicked satires of American paranoia to raise narrative ambiguity into high art.

3. Golden Cages

The 21st Century’s inaugural decade boasted so many terrific—even groundbreaking—programs that referring to the 2000s as American television’s true Golden Age became a common refrain among viewers, critics, and scholars. 24 (2001-2010 & 2014), The Shield (2002-2008), The Wire (2002-2008), Karen Sisco (2003-2004), Arrested Development (2003-2006, 2013, & 2018-2019), Deadwood (2004-2006 & 2019), Battlestar Galactica (2004-2009), Invasion (2005-2006), The Office (American remake, 2005-2013) Brotherhood (2006-2008), Friday Night Lights (2006-2011), 30 Rock (2006-2013), Dexter (2006-2013), Big Love (2007-2011), Californication (2007-2014), Breaking Bad (2008-2013), Mad Men (2008-2015), Parks and Recreation (2009-2015), and Treme (2010-2013) are all fascinating examples of television narrative, in some cases problematic, but just as frequently masterful—if not outright masterpieces.

If we trust reviews, scholarly articles, and message-board postings published between 2000 and 2010, Arrested Development is the situation comedy’s apotheosis, while The Wire is a work of television genius. This list could expand, but the point is that, although no single year or decade qualifies as American television’s Golden Age because this term is an elitist canard, references to the Golden Age of American Television—whenever it happens to be—will continue, just as identifying the Golden Age of Television in other nations will surely proceed. The tendency to announce golden ages, after all, is not exclusively American, with British series Fawlty Towers (1975-1979), The Office (British original, 2001-2003), and Doctor Who (1963-1989, 1996, & 2005-Present) achieving as much praise as any American program.

Since the 1970s, premium- and basic-cable channels, DVD and Blu-ray technology, and streaming services have challenged the major television networks’ monopoly over producing, distributing, and broadcasting primetime television. The result is an era, beginning in 1981, that’s offered audiences more provocative programs than any prior point in history although every previous decade can boast its share of complicated, challenging, and skillful series.

And the term Golden Age remains problematic for another reason. Every decade since television’s inception as a narrative medium has produced programs so terrible that they’re best forgotten: My Mother the Car (1965-1966); Full House (1987-1995); Baywatch (1989-2000); and Walker, Texas Ranger (1993-2001) are obvious offenders. Mediocre television seems more prevalent than either exceptional or execrable series, so no purified Golden Age of Television has ever existed (just as, by this criterion, no cultural Golden Age has ever existed).

Still, thanks to the digital availability—on demand, on disc, and online—of vast amounts of American television, along with cable channels devoted to broadcasting older television (Nick at Nite, TVLand, and MeTV are only three examples), viewers have never had a better opportunity to refresh themselves about the cultural heritage that television represents. The existence of so many sophisticated, thoughtful, and challenging programs allows the medium’s admirers to make an argument unimaginable during the 1960s: People should watch more television—or at least more great television—to better understand, appreciate, and enjoy the medium’s pleasures and possibilities.

Although we’ve passed the day when that global communication system known as “the Internet” has outstripped television as humanity’s most pervasive, influential, and profitable mass medium, the fact that—if only you search long and hard enough for it—so much television produced in every nation and language is available somewhere online testifies to TV’s enduring popularity, longevity, and influence.

The upshot to these observations is that debating the dates of the Golden Age (or Golden Ages) of Television seems less intriguing—and certainly less fun—than discussing television’s best work, so, with this proviso in mind, I issue this clarion call:

Stream on, dear reader, stream on!

FILES

WORKS CITED

Bianculli, David. Teleliteracy: Taking Television Seriously, Continuum Books, 1992.

Gitlin, Todd. “Look Through the Screen,” in Watching Television: A Pantheon Guide to Popular Culture, edited by Gitlin, Pantheon Books, 1986, pp. 3-8.

Halberstam, David. The Fifties, Villard Books, 1993.

McGrath, Charles. “The Triumph of the Prime-Time Novel,” New York Times Magazine, 22 October 1995, pp. 52+, http://www.nytimes.com/1995/10/22/magazine/the-prime-time-novel-the-triumph-of-the-prime-time-novel.html?pagewanted=all.

Minow, Newton M. “Television and the Public Interest,” Address to the National Association of Broadcasters, 9 May 1961, http://www.americanrhetoric.com/speeches/newtonminow.htm.

Oates, Joyce Carol. “Why Hill Street Blues Is Irresistible,” TV Guide, 1 June 1985, pp. 5+.

Steiner, George. Introduction to The Trial: The Definitive Edition by Franz Kafka, Schocken Books, 1992, pp. vii-xxi.

Thompson, Robert J. Television’s Second Golden Age: From “Hill Street Blues” to “ER,” Syracuse University Press, 1996.

Zicree, Mark Scott. The Twilight Zone Companion, Bantam Books, 1982.

FURTHER READING

Adorno, Theodor W., and Max Horkheimer. “The Culture Industry: Enlightenment as Mass Deception.” In Dialectic of Enlightenment: Philosophical Fragments, edited by Gunzelin Schmid Noerr, translated by Edmund Jephcott, first published in 1947, Stanford University Press, 2002, pp. 94-136.

Benjamin, Walter. “The Work of Art in the Age of Mechanical Reproduction.” In Illuminations, edited by Hannah Arendt, Schocken Books, 1968, pp. 217-251.

Berger, John. Ways of Seeing, first published in 1972, British Broadcasting Corporation and Penguin Books, 2003.

Canby, Vincent. “From the Humble Mini-Series Comes the Magnificent Megamovie,” New York Times, 31 October 1999, http://www.nytimes.com/1999/10/31/arts/from-the-humble-mini-series-comes-the-magnificent-megamovie.html?pagewanted=all.

Edgerton, Gary R., and Jeffrey P. Jones, editors. The Essential HBO Reader, University Press of Kentucky, 2008.

Fiske, John. Television Culture, first published in 1987, Routledge, 2006.

Gitlin, Todd. Inside Prime Time, first published in 1983, University of California Press, 2000.

Graham, Allison. Framing the South: Hollywood, Television, and Race during the Civil Rights Struggle, Johns Hopkins University Press, 2003.

Gray, Herman. Watching Race: Television and the Struggle for Blackness, first published in 1995, University of Minnesota Press, 2004.

Lavery, David, editor. Reading Deadwood: A Western to Swear By, Reading Contemporary Television Series, I.B. Tauris, 2006.

Longworth, James L., Jr. TV Creators: Conversations with America’s Top Producers of Television Drama, Syracuse University Press, 2000.

Lotz, Amanda D. The Television Will Be Revolutionized, first published in 2007, 2nd edition, New York University Press, 2014.

Mander, Jerry. Four Arguments for the Elimination of Television, first published in 1978, Perennial, 2002.

McCabe, Janet, and Kim Akass, editors. Quality TV: Contemporary American Television and Beyond. I.B. Tauris, 2007.

Mittell, Jason. Genre and Television: From Cop Shows to Cartoons in American Culture, Routledge, 2004.

Newcomb, Horace, editor. Television: The Critical View, first published in 1976, 6th edition, Oxford University Press, 2000.

Peacock, Steven, editor. Reading “24”: TV Against the Clock, Reading Contemporary Television Series, I.B. Tauris, 2007.

Rapping, Elayne. Law and Justice as Seen on TV, New York University Press, 2003.

Siegel, Lee. Not Remotely Controlled: Notes on Television, Basic Books, 2007.

Spiegel, Lynn, and Jan Olsson, editors. Television after TV: Essays on a Medium in Transition, Duke University Press, 2004.

Jarvis, Robert M., and Paul R. Joseph, editors. Prime Time Law: Fictional Television as Legal Narrative, Carolina Academic Press, 1998.

Steyn, Mark. “The Maestro of Jiggle TV,” The Atlantic, September 2006, pp. 146-47.

Teachout, Terry. “The Myth of ‘Classic TV,’” in A Terry Teachout Reader, Yale University Press, 2004, pp. 174-77.

Torres, Sasha, editor. Living Color: Race and Television in the United States, Duke University Press, 1998.

Vande Berg, Leah, Lawrence A. Wenner, and Bruce E. Gronbeck. Critical Approaches to Television, Houghton Mifflin, 2004.

Williams, Raymond. Television: Technology and Cultural Form, first published in 1974, Routledge, 2003.

Yeffeth, Glenn, editor. What Would Sipowicz Do?: Race, Rights and Redemption in “NYPD Blue,” BenBella Books, 2004.

NOTES

George Steiner, introduction to The Trial: The Definitive Edition, by Franz Kafka, Schocken Books, 1992, pg. vii.

Robert J. Thompson, Television’s Second Golden Age: From “Hill Street Blues” to “ER,” Syracuse University Press, 1996, pg. 19.

Todd Gitlin, “Looking Through the Screen,” in Watching Television: A Pantheon Guide to Popular Culture, edited by Gitlin, Pantheon Books, 1986, pg. 3.

Thompson, Television’s Second Golden Age, pg. 11.

David Halberstam, The Fifties, Villard Books, 1993, pg. 508.

Thompson, Television’s Second Golden Age, pg. 12.

Marc Scott Zicree, The Twilight Zone Companion, Bantam Books, 1982, pg. 8.

Ibid.

David Bianculli, Teleliteracy: Taking Television Seriously, Continuum Books, 1992, pg. 272.

Newton N. Minow, “Television and the Public Interest,” Keynote Address, National Association of Broadcasters, Washington, D.C., 9 May 1961, https://www.americanrhetoric.com/speeches/newtonminow.htm.

Charles McGrath, “The Triumph of the Prime-Time Novel,” New York Times Magazine, 22 October 1995, 52+, http://www.nytimes.com/1995/10/22/magazine/the-prime-time-novel-the-triumph-of-the-prime-time-novel.html?pagewanted=all.

Ibid.

Thompson, Television’s Second Golden Age, pg. 34.