Rebel with a Cause: Barack Obama’s Unfinished Presidency

Retro Book Review (#3) of Richard Wolffe's Renegade: The Making of a President

Note to The Vestibule’s subscribers: My previous post (“Dreams Deferred and Deserved: Barack Obama’s Unfinished Candidacy”) evaluates Barack Obama’s 1995 book, Dreams from My Father: A Story of Race and Inheritance. This assessment was first published, circa September 2008, in Belles Lettres: A Literary Review, the then-flagship newsletter of Washington University in St. Louis’s Center for the Humanities. Running from 2002 to 2013, Belles Lettres was the brainchild of my dissertation advisor (and, I’m happy to say, my friend), Dr. Gerald Early, whose editorial leadership was crucial to Belles Lettres’s success. I was happy to contribute my thoughts about Obama’s book in its September/December 2008 issue, whose print version appeared two months before the 2008 American presidential election. This piece, I’m also happy to say, was well received by many Belles Lettres readers, some of whom contacted Gerald (who duly passed along their messages) to express their approval, while others emailed their compliments directly to me.

One correspondent, however, was so enraged by my not-so-hidden argument that Obama was a better presidential candidate than John McCain that he took the time to locate my University of Guam office phone number, call me in the middle of the night (Guam time), and leave perhaps the nastiest phone message I’ve ever received. According to this seasoned observer of American politics, I was “dumb,” “hopelessly naïve,” and, if memory serves (I forgot to preserve this message before junking that phone or I’d share it with you here), an “example of everything that’s wrong with higher education” (or words to that effect). Oh, and I needed to learn to write better so that I didn’t sound like the “snotty little trust-fund baby” he knew that I was.

If I’d been there to take this call, I might’ve laughed into the receiver, or, more likely, told this intellectual giant how happy I was to disappoint him. You see, Mr. Peckerwood (I would’ve said), I’m the furthest thing from a trust-fund baby that exists, being the son of two blue-collar workers from a small Iowa town named Moville, one of whom—my father, Merlin Boyd Vest (1933-1981)—was killed in a work-related traffic crash in October 1981. More to the point, according to my mother, Delores Madge Vest (1938-2017), on the day of his death, Dad was looking forward to making more than $30,000 per year—a record sum for the son of a subsistence farmer (my grandfather, William Boyd Vest), who, according to family legend, never made more than $5,000 per year during his 73 years of life—when 1982 arrived alongside the triennial raise that my father was scheduled to receive as a longtime employee of Woodbury County, Iowa’s road-maintenance department.

I tell this anecdote not to aggrandize myself as a working-class hero who, misunderstood by his contemporaries, must prove (and provide) his blue-collar bona fides, but to demonstrate how easily—and how stupidly—people who don’t know what they’re talking about irritate the people who do. History has vindicated everyone who voted for Barack Obama, if for no other reason than John McCain decided that Sarah Palin was qualified to be Vice President of the United States—meaning, to employ an old aphorism, that McCain had no qualms about Palin being a heartbeat away from the presidency—in a misjudgment so spectacular that it once and for all demolished McCain’s reputation as a political maverick, instead confirming that he was just another inside-the-Beltway hack who thought that selecting a running mate almost no one expected was a bold and innovative choice when, in reality, it was as cynical a political ploy as any presidential candidate had pulled in 50 years.

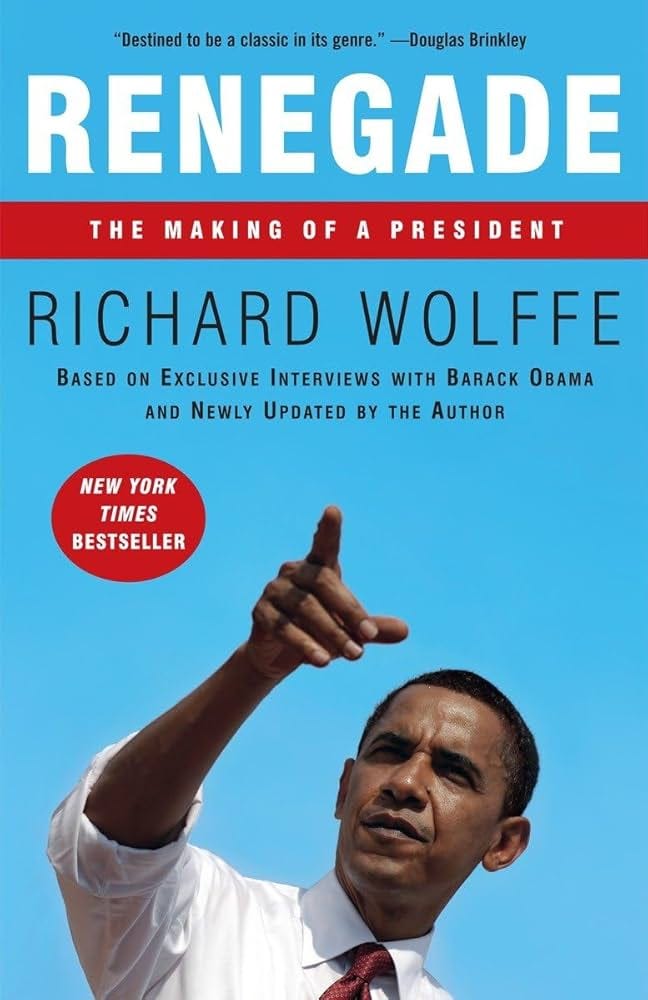

That bullet dodged, Obama’s inaugural year as president—after those consequential first 100 days, during which he signed a recovery act that, while it might’ve helped stabilize a national economy plunging into the abyss of financial turmoil, didn’t restructure that economy to privilege workers and their labor over the titans of capital who created the Great Recession in the first place—was rocky, to say the least. Given these givens, when Gerald asked me to review Richard Wolffe’s campaign chronicle Renegade: The Making of a President, I couldn’t resist, and, after reading Wolffe’s book during July 2009, I wrote the following essay, which Gerald published in Belles Lettres’s September/December 2009 issue (exactly one year after “Dreams Deferred and Deserved” saw the light of day).

Gerald retitled this piece “A Rebel’s Rendezvous with Destiny,” which is both more poetic and more accurate than my original title, under which the piece appears here: “Rebel with a Cause.” Sometimes a good editor—no, make that a great editor, which Gerald certainly is—helps clarify what the writer can’t see or says what the writer should’ve said, only better, so please, dear readers, decide for yourselves which title best describes this essay.

Like my previous post, I’ve aligned this review with The Vestibule’s house style, but I haven’t updated its language to place it in the past, meaning that this piece reads as if you’re encountering it in 2009.

I’m uncertain if reading “Rebel with a Cause” can or will mitigate any of the anxieties we’re experiencing as the Second Trump Regime’s ongoing political disasters pile atop themselves at a pace designed to stun us, to discombobulate us, and to depress us, so I can only encourage you, dear readers, to enjoy your lives as much as possible while we all, in the words of famed union organizer and labor activist Mary G. Harris Jones (a/k/a Mother Jones), “pray for the dead and fight like hell for the living.”

That’s the only course we have left and, for good measure, the only one we need.

All the best (and all my hopes)—Jason

Renegade: The Making of a President

Written by Richard Wolffe

Published by Crown Publishers

2009

356 pages

ISBN 0-307-463-125

$26.00

1. Mr. President

Barack Obama is President of the United States of America.

This fact, no matter how obvious, hasn’t prevented lunatic fearmongers from vociferously doubting its truth as 2009 unfolds. The occasionally stunning displays of contempt against Obama by Orly Taitz, the so-called “Birther Movement,” the Tea Party tax protesters, South Carolina Representative Joe Wilson, Glenn Beck, and Fox News seem peculiarly American in their misplaced passion, prideful ignorance, and proxy racism, so the statement bears repeating, unequivocally and univocally: Barack Obama is President of the United States of America.

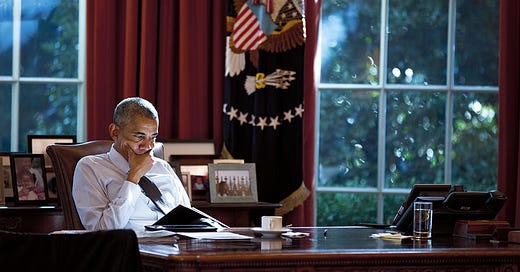

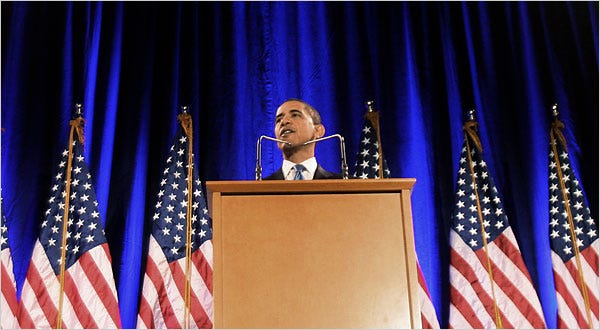

This outcome, no matter how inevitable it may strike the nostalgically minded, is, as Richard Wolffe argues in his fine book Renegade: The Making of a President, among the most improbable political victories in American history. Wolffe makes this claim partly because Obama’s election as the nation’s first African American chief executive is a development that many citizens (including myself) never fully believed could happen until they watched Obama’s 20 January 2009 inaugural address. Some viewers were misty-eyed by the sight, others awed by the symbolism, and yet others unhinged by the reality of a biracial American president. Wolffe, who covered Obama’s campaign from its first moments for Newsweek magazine and MSNBC, knows as well as anyone that, in presidential politics, expectations can buoy or sink candidates. Renegade recounts how Obama not only survived but also surmounted the crushing pressures that confronted his unlikely White House bid.

Wolffe, as befits his journalistic calling, extensively interviewed Obama, his family, his staff, his volunteers, and his voters during the long campaign (21 months from Obama’s official 10 February 2007 announcement on the steps of Springfield, Illinois’s state capitol, through the Democratic Party’s protracted primary process, and onto 4 November 2008’s general election). These conversations, particularly Wolffe’s ceremoniously billed “exclusive” dialogues with Obama, give Renegade a frenetic behind-the-scenes, on-the-trail, near-the-stump, back-of-the-plane intimacy. Obama emerges as a thoughtful, ambitious, friendly, and prickly man who, as Gerald Early (channeling Bill Buckley) noted in Belles Lettres’s pages last year (“The Singular Education of Young Man McCain,” September/December 2008), was riding the express train of history to victory (if not glory) in a contest that lasted far too long.

Wolffe’s campaign-history-cum-candidate-biography is one of several books that publishers, desperate to prop up their ailing print businesses by capitalizing on Obama’s victory, rushed to press. Chuck Todd’s and Sheldon Gawiser’s How Barack Obama Won: A State-by-State Guide to the Historic 2008 Presidential Election (Vintage), Earl Ofari Hutchinson’s How Obama Won (BookSurge Publishing), Greg Mitchell’s Why Obama Won: The Making of a President 2008 (BookSurge Publishing), Evan Thomas’s “A Long Time Coming”: The Inspiring, Combative 2008 Campaign and the Historic Election of Barack Obama (PublicAffairs), Larry J. Sabato’s edited collection The Year of Obama: How Barack Obama Won the White House (Longman), and Obama campaign manager David Plouffe’s The Audacity to Win: The Inside Story and Lessons of Barack Obama’s Historic Victory (Viking) all purport to tell the same story: how the nation’s first Black president challenged old-boy politics, entrenched Beltway interests, America’s racial divisions, and the nation’s complacent electorate to win a consequential election that, the pundits continually reminded us, would set America’s course for the next quarter-century.

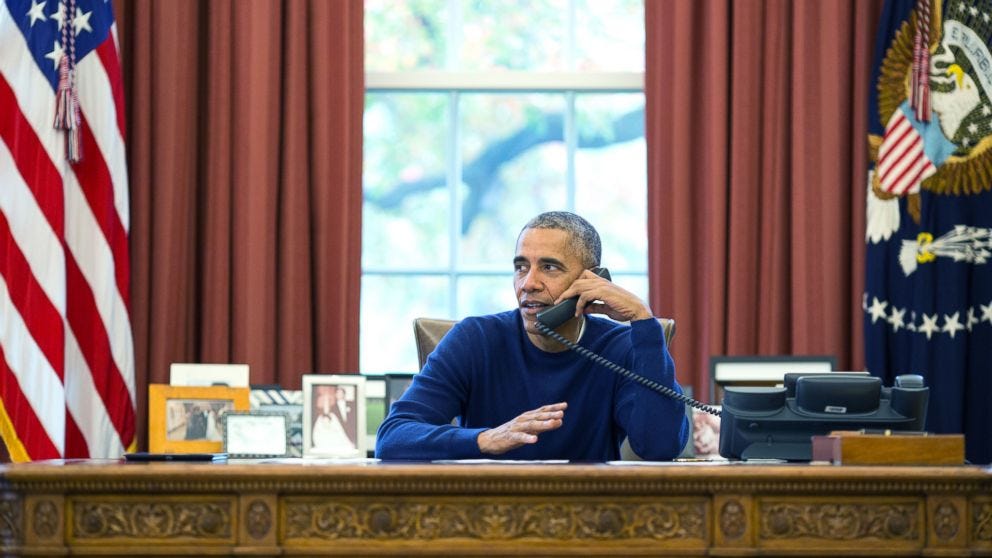

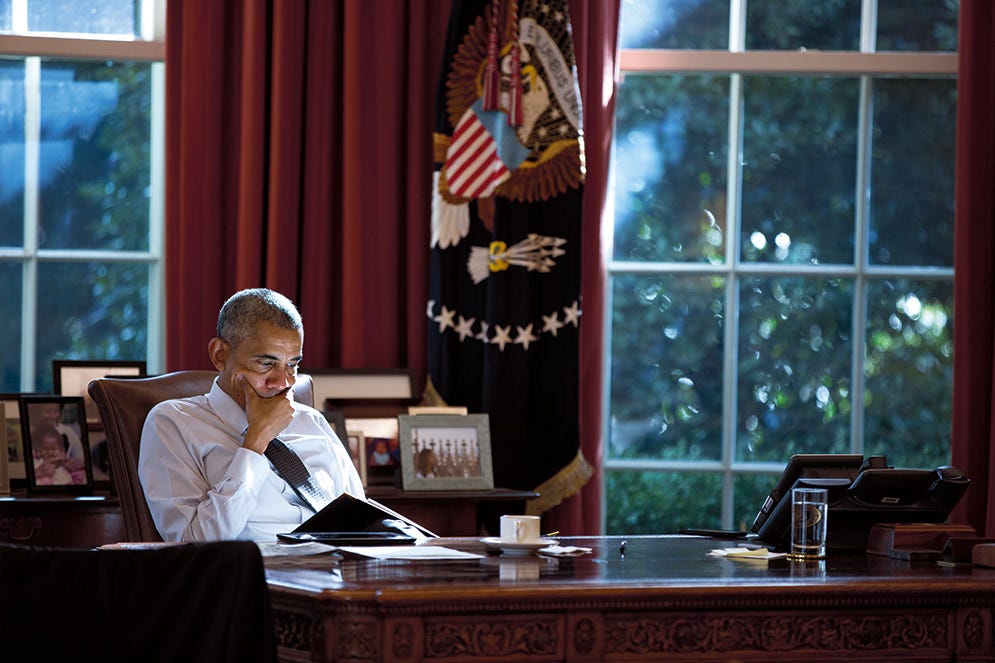

As these books’ titles, themes, and sentiments indicate, Obama’s election, even more than his candidacy, has become, in the year since his victory, a watershed event. Critical readers, no matter how true this historical judgment may be, can’t help doubting the back-slapping praise these books imply about Obama’s presidency, which—despite its first-year successes and stagnations—can too quickly assume an aura of unassailable nobility that the president himself takes pains to puncture. Obama’s somber and sober inaugural address refused the hagiographic sentiment that the just-quoted subtitles suggest, while his resolutely wonkish press conferences seem designed to downplay the historic significance—by now both profound and quotidian—of Obama standing before the White House press corps; discussing how he intends to save the financial system, extend health care to millions of uninsured Americans, and rebuild the nation’s image abroad; answering questions with literate responses that every reporter in the room (save Helen Thomas) seems startled to realize are still possible from the Commander-in-Chief; and, much to the chagrin of his detractors, being presidential.

2. Candid Candidacy

Renegade (named after Obama’s Secret Service call sign) strikes a different tone than the resolutely admiring—and therefore untrustworthy—campaign profiles that metastasized across magazine covers, news channels, and online blogs during 2008, even if, by the book’s conclusion, Wolffe’s professional, personal, and political respect for the candidate (and future president) is evident. The first chapter, titled “Change,” mixes Wolffe’s breathless account of how Obama spent Election Day 2008 with salient observations, intelligent analyses, and historical tidbits that illustrate just how conscious Obama was of the effect that his presidency might have on domestic and global politics.

Wolffe writes in an engaging, accessible, and conversational style that places readers close to the events and to the candidate himself. One of the freshest comments is also the shortest: “Across the nation,” Wolffe writes of Election Night 2008, after Obama’s popular and electoral vote margins are secure, “city streets are crime free and Obama crazy.”1 This sentence causes the reader to think back to 4 November 2008 to realize that, despite the observation’s implicit hyperbole, it nicely captures the fevered emotions that greeted Obama’s election. Not all those emotions were positive, of course, as anyone who watched John McCain’s supporters booing Obama’s name at McCain’s initially-awkward-yet-finally-gracious concession speech knows, but Wolffe succeeds in depicting that night’s intensity, importance, and joy in only a few words.

This comment also prepares readers for Renegade’s first major revelation about Obama’s awareness of his campaign’s impact. After the new president’s Grant Park victory speech, watched in person by thousands of Chicago residents and out-of-town citizens braving the nighttime cold, Wolffe reports that David Axelrod, Obama’s close friend and campaign adviser,

is in tears, catching sight of several African American children in the crowd. They, too, are crying as they wave American flags. He recalls the earliest days of their quest for the White House, when Michelle [Obama] asked Barack what he thought he could accomplish as president: “I know this,” he told her almost two years earlier, in Axelrod’s conference room. “The day I take the oath of office, the world will look at us differently. And millions of kids across this country will look at themselves differently. That alone is something.”2

Obama’s detractors might find this statement arrogant, even elitist (as they seem to find all his statements, even the banal ones), but Wolffe cites it to prove that Obama, while an inherently pleasant fellow, is also a fiercely intelligent and ambitious politician. He’s also a man, no matter how frequently supporters and media commentators proclaim him to be the Black candidate that transcends race, who understands how his biracial heritage shaped the campaign’s identity. No one, after all, discussed how John McCain’s election would be a victory for older Americans or how Joe Biden’s election as vice president would be a boon to chatterboxes everywhere. Not even Sarah Palin’s bizarre selection as McCain’s running mate was perceived as the stirring triumph for women that Obama’s candidacy was for Black Americans, or how Obama’s campaign became a forum for American race relations. Obama, Renegade slowly (but surely) reveals, knew that this development would occur even if he publicly downplayed its reality. Wolffe’s book, in other words, substantiates what thoughtful observers knew all along to be true.

Obama’s rise to the White House, Renegade argues better than any other book, was no accident. Obama’s victory combined many factors, including guile, confidence, luck, and fortitude. This last element is a repeated theme—really, a leitmotif—in Wolffe’s account. He doesn’t fawn over Obama’s toughness or the candidate’s ability to endure sometimes vicious attacks (from McCain and Palin during the general election, as well as from Hillary Clinton and Joe Biden during the primaries), but Wolffe regularly reminds the reader, as one pregnant passage comments, that “a fear of failure and a vaulting ambition were the twin forces that drove Obama onward and upward.”3

Ryan Lizza made much the same point in his 21 July 2008 New Yorker article “Making It” by noting that Obama used every available legal political tactic to knock opponents out of his way when beginning his Illinois political career. Chicago, it seems, either hardens its elected officials or destroys them (and, as disgraced ex-governors George Ryan and Rod Blagojevich prove, frequently does both). Obama, in other words, knows how to prevail in political street brawls despite his lofty rhetoric. Renegade offers so many examples of Obama’s ability to recognize, improve, and ameliorate his flaws (a healthy ego, according to Wolffe, being as persistent a problem for Obama as it’s been for other presidents) that the reader can’t escape concluding that Obama, even if he stepped onto the national stage at a propitious historical moment, created his own luck as much as the events of his era did.

3. Campaign Blues

Renegade’s most gripping, powerful, and lucid chapter is the fourth, simply titled “Failure.” Wolffe examines how Obama and his campaign team, after developing an impressive (and nearly unprecedented) ground operation in Iowa that allowed them to beat both Hillary Clinton and John Edwards in that state’s 2008 caucuses, came to New Hampshire too proud of their hard-fought victory. “The intoxicating feelings of triumph and hubris overpowered the workaday sense of caution and humility that had characterized Iowa,” Wolffe notes. “In private, the candidate seemed uncomfortable, unsettled with his own success; in public, he drank deep from the adoring crowds.”4

This declaration has the ring of authenticity, not because it unfairly criticizes Obama, but because it shows such restraint. Obama fumbled the New Hampshire primary so badly that some commentators, campaign workers, and longtime Democratic operatives wondered if he could clinch the party’s nomination (or even survive until Super Tuesday). David Axelrod—whom Wolffe variously describes as Obama’s best friend, biggest fan, and consigliere—eventually stated the case bluntly, but accurately: “We were still basking in the afterglow of Iowa and Hillary looked like she was working her ass off. She looked like she really wanted it. It felt like we were up at twenty thousand feet and she was at ground level, grinding out the votes. It looked like she was working harder than we did.”5

Obama’s reaction to the New Hampshire defeat, Wolffe persuasively argues, saved his campaign and won him the presidency. The candidate didn’t panic, fire his staff, or indulge in vicious recrimination. Obama instead told Valerie Jarrett, his longtime friend (and Chicago mayor Richard M. Daley’s former deputy chief-of-staff), “It’s going to be the best thing that could have happened. We’re going to be fine.”6 The candidate then addressed thousands of supporters in Nashua South High School, delivering his now-famous “Yes We Can” speech that the Black Eyed Peas’ will.i.am and director Jesse Dylan immortalized in an instantly famous online music video. This adult approach, in Wolffe’s eyes, distinguished Obama from all opponents on both sides of the political aisle and proved to his staff, his supporters, and enough undecided voters that Obama could, in fact, lead the United States of America.

Wolffe, however, doesn’t go easy on the candidate. Obama’s naïveté about the rigors of presidential campaigning occasions this nicely textured analysis: “Obama was failing the test, and he knew it. As much as he had tried to understand what a campaign would be like, he had no idea how intense the attention would be. ‘It’s like a public colonoscopy,’ he told his friend [Marty] Nesbitt [a Chicago airport-parking-lot magnate]. ‘It’s more rigorous, more in-depth than I ever imagined.”7 Obama’s memorable simile provides perfect counterpoint to Wolffe’s criticism. What, after all, did Obama imagine presidential politics would entail? While no human being may be able to prepare for such exposure, Wolffe suggests that Obama should’ve known it was coming.

Obama, at many points, hated campaigning (as Biden, McCain, and Palin undoubtedly did). He became irritable. He missed his family. He longed for relief from the daily grind of fundraisers, stump speeches, and media appearances. He questioned his decision to enter the race. Wolffe’s narrative brings these frustrations alive for his readers, while also emphasizing how Obama was able, on nearly every occasion, to push these feelings aside.

Wolffe’s grand metaphor for Obama the politician, the nominee, and the President-Elect is his renegade status: He was, after all, an insurgent candidate that few people expected could win. The general election, early in 2007, looked as if it would pit Rudy Giuliani against Hillary Clinton. Or John McCain against Hillary Clinton. Or Rudy Giuliani against John Edwards. Or Fred Thompson against Al Gore (if Gore, as some Democrats hoped, staged an eleventh-hour coup). The possibility that Barack Obama could rise from first-term senator to President in four years was, in Wolffe’s words, “also preposterous and quixotic, at least in the judgment of the greatest political minds in the nation’s capital.”8

Renegade reveals that President George W. Bush’s assessment of Obama’s chances, while conventional—and even reasonable—in its conclusions, proved spectacularly wrong (causing readers who endured eight long years of Bush’s presidency to question Wolffe’s contention that Bush is one of America’s greatest political minds). Bush, just before Obama’s February 2007 announcement, thought the Illinois senator to be “certainly a phenom and very attractive.”9 The primary process, however, is “really tough and rightly so. It exacerbates your flaws and tests your character. And I don’t think he’s been around long enough to stand it. I may be wrong. The process may forge a steel that I didn’t anticipate.”10

While some readers may be hard-pressed to believe that Bush uttered these words aloud (they resemble press-release verbiage more than the 43rd president’s verbally dyslexic public statements), they nonetheless nimbly evaluate Obama’s prospects at the beginning of his campaign. Renegade’s strength lies in how expertly it fuses political analysis, journalistic reportage, campaign exposé, and history lesson. Wolffe also illuminates previously unknown, underreported, or little-known facts, including the revelation that Obama’s ill-advised 2000 decision to challenge Bobby Rush, a former Black Panther and four-term congressman from Chicago’s South Side, nearly cost Obama his marriage.

The financial, familial, and emotional strains were nearly too much for Michelle Obama: “His daughter Malia was sick with a cold and his wife was unhappy with both his political career and their marriage. She disagreed with his decision to run, was dismayed by his failure to help around the house, and was barely on speaking terms with him.”11 This image so contrasts the strong relationship and happy photos of the Obama family now carpeting the Internet that it points out how the Obamas, long before they achieved fame or wealth, struggled with everyday problems. Renegade, in parts and in whole, summarily disproves the caricature of Obama as an elitist snob concerned only with personal advancement by illustrating how the man tripped over himself early in his political career.

4. Racing the White House

Losing decisively to Rush in 2000, however, taught Obama the most significant lesson of his political career. Race, Wolffe argues in Chapter Five (titled “Barack X”), has always been a factor in Obama’s public life (and, as the first year of his presidency has demonstrated, always will be). Although Obama, while an Illinois state senator, helped reform Illinois’s death-penalty system and helped change the state’s approach to racial profiling, he “was taken aback by racial politics in his days as a street-level activist and was ill equipped to appeal to people as an African American.”12

Jerry Kellman, Obama’s mentor during his community-activist days, finds this difficulty to be a political strength. Obama’s gift, according to Kellman, “is diversity. Not just diversity of race and people, but of holding different ideas together and understanding how they relate.”13 This quotation begins to explain President Obama’s baffling preoccupation with bipartisanship, particularly his efforts to reach out to Republican lawmakers who consistently rebuff his overtures. Wolffe’s observation also hints at the most controversial—and therefore largely unspoken—truth of Obama’s candidacy: that his biracial heritage and self-identification as a Black American distinguish him from the electorate’s largest voting bloc.

Wolffe notes, in perhaps Renegade’s most perceptive passage, precisely what Obama’s racial background means to Black Americans after reminding the reader that Black voters didn’t initially support Obama in droves or in the mindless fashion that Rush Limbaugh and Glenn Beck claimed they would because, shockingly to these media racists, Black voters are no more monolithic than White voters:

To Obama’s friends and family, the questions posed about his racial identity or his readiness for presidential power seemed to echo their own experience. For years, they had struggled to overcome the notion that this wasn’t their time, or they weren’t quite ready for their elite schools or high-flying careers. They had encountered the refined racism that could not conceive of a person of color in a position of leadership. And they had overcome the defensive crouch that kept African Americans down, adjusting their hopes lower, just in case of defeat or disappointment. Obama’s presidential run was not just a test of his ability to cross the lines that divided voters. He was breaking the rules about what a black candidate could aspire to, and what black voters should believe of themselves and their country. His skills and experience were not unique to Barack Obama. They were shared by many of his friends and a far wider generation of well-educated, professional, younger African Americans.14

This analysis echoes the writings of Earl Ofari Hutchinson, Eugene Robinson, Clarence Page, and Ta-Nehisi Coates by staring the complicated political effects of race and American racism in the face. Obama inspired people across racial, gender, and political lines, but to some of them, he was, unlike boxer Jack Johnson, forgivably Black by not operating in the same fashion as more flamboyant figures such as Jesse Jackson and Al Sharpton.

Obama, indeed, has publicly distanced himself from racial controversies as often as possible during his campaign (with the notorious exception of Reverend Jeremiah Wright) and his presidency (with the notable exception of his 22 July 2009 comments about the arrest of Harvard professor Henry Louis Gates Jr.), but he knew, from bitter experience, that his skin color mattered. Those people (particularly Republicans) who hoped that Obama’s transcendent identity would absolve America of its racial sins were, Wolffe’s book makes clear, simply wrong in their aspirations. And, as the Birthers, the Tea Baggers, and Glenn Beck have shown, Obama will never be allowed by fringe elements of the American electorate to heal America’s racial wounds.

Renegade, good as it may be on this and other points, has some notable flaws. Wolffe’s repeated use of the word insurgent, especially when the book discusses the Iraq War, uncomfortably associates Obama with fighters whose negative media portrayal—fair or unfair—reminds readers of the far right’s false allegations that Obama is a secret Muslim who wishes to destroy America. Some members of Obama’s inner circle certainly thought of him as an insurgent candidate, but this term doesn’t correctly characterize Obama once he secures the Democratic Party’s nomination. At that point, Obama has gone from being an outsider to the consummate insider, which Wolffe’s book occasionally ignores.

Chapter Six, titled “Game Changer,” takes Obama’s well-known love of basketball as an extended metaphor for his campaign’s direction, difficulties, and triumphs. Such sports analogies always run aground, particularly when applied to the consequential aspects of presidential politics, so Wolffe should’ve resisted the tendency to indulge the claptrap talk that characterizes ESPN’s SportsCenter and Sports Illustrated’s editorial existence. HBO’s Bryant Gumbel made these comparisons much more elegantly in his 15 April 2008 Real Sports segment “The Love of the Game” anyway, so Wolffe, even if he can’t be charged with conceptual plagiarism, can at least be rebuked for saying what Gumbel said better, only worse.

5. Yes, He Can?

Obama’s presidency, as it nears the end of its first year, seems beset on all sides. Republicans and their surrogates—when not calling Obama a liar, a weakling, a witch doctor, a socialist, a Communist, a Nazi, a Muslim, an Israel hater, Hitler, Stalin, Pol Pot, Idi Amin, or some strange fusion of the Predator alien and a Klingon—seem content to oppose every policy he proposes, every statement he utters, and every idea he advances in a fervent attempt to make Americans forget the damage they inflicted on the country’s economy, international reputation, and civic life during the Bush years. Some Democrats, not content to let Republicans win the media shoutfest that now passes for mainstream journalism, deride Obama as a smooth-talking capitalist; a war monger; a torturer; a bought-and-paid-for corporate shill; or a strange conflation of George W. Bush, Ronald Reagan, and Richard Nixon who happily sells out the common person to keep the bankers happy.

Before last year’s general election, I wrote that, should Obama become president, he would disappoint every person who voted for him and every person who didn’t. This safe prediction has now become reality. Obama’s defense of a bank bailout that allowed corporate executives to retain outrageously plush bonuses while autoworkers saw their contracts shredded, his extension of certain Bush-era security measures and PATRIOT Act provisions, his apparent willingness to compromise universal health care down to the nub in hopes of securing Republican support, and his dispatch of thousands of American soldiers to Afghanistan have progressive supporters enraged at Obama’s betrayal of what they believe are his core principles.

Some of these doubts are well-founded, so Obama’s advocates have every right to pressure him to pursue the agenda that he promised during his historic campaign. But the hard facts of governance, as opposed to the airy thrills of electioneering, force Obama to be a pragmatic centrist far more than his critics left, right, and center realize. The magnitude of the wreckage caused by Bush’s Administration means that Obama can’t repair eight years of economic, political, and social decline even if he’s granted two terms in office.

His presidency, so far at least, isn’t what people had hoped, but it’s what can we can reasonably expect given the challenges that Obama faces. When we recall the anemic first years of the Bush 43, Clinton, Bush 41, Reagan, Carter, and Ford presidencies, Obama’s freshman effort gains credibility, if not luster. Obama, for instance, has promised great change, particularly to the healthcare system, that he simply must deliver. Yet it won’t happen all at once, so prodding the president by seeming impatient, while maintaining the inner equipoise that Obama so readily projects, seems the best course for now.

Richard Wolffe is confident that Obama will improve as his presidency continues because Obama’s followed this pattern throughout his personal and political lives. Time, of course, will tell. Reading Renegade: The Making of a President not only confirms Wolffe’s talent as a political journalist and election chronicler but also makes its audience more sanguine about Obama’s chances. As campaign autopsies go, Wolffe’s book maintains its reader’s interest, engages its reader’s mind, and tugs at its reader’s heartstrings by demonstrating how transformative a leader Obama has been and can be.

It also gives its reader (or, at least, this reader) some small measure of comfort by thoroughly explaining how an inescapable, improbable, and incredible fact of life came to be.

This fact, no matter who attempts to diminish it, remains reason for hope.

Barack Obama is President of the United States of America.

FILES

NOTES

Richard Wolffe, Renegade: The Making of a President, Crown Publishers, 2009, pg. 18.

Ibid., pp. 19-20.

Ibid., pg. 121.

Ibid., pg. 105.

Ibid., pg. 112.

Ibid., pg. 115.

Ibid., pp. 124-125.

Ibid., pg. 3.

Ibid., pg. 4.

Ibid.

Ibid., pg. 120.

Ibid., pg. 154.

Ibid.

Ibid., pg. 155.