Red Balls & Blue Bloods

Three decades later, Homicide: Life on the Street remains an essential American television series.

Note to The Vestibule’s subscribers: Richard Belzer’s death on 19 February 2023 is a tremendous loss and, coming so soon after Annie Wersching’s passing on 29 January 2023, delivers a one-two punch to lovers of great acting. Rather than lament the universe’s unfairness in taking another terrific talent from us, I instead offer my condolences to Belzer’s family, friends, and colleagues.

Belzer’s remarkable performance as Detective (later Sergeant) John Munch over 23 years—as a principal cast member in all seven seasons of Paul Attanasio’s Homicide: Life on the Street (1993-1999) and in the first 15 seasons of Dick Wolf’s Law & Order: Special Victims Unit (1999-Present), with a guest appearance in SVU’s Season 17—makes Belzer a record-setter. As I write these words, he occupies the Number 2 spot on the list of American primetime-television performers who’ve played the same character over the longest continuous span of time, outlasted only by his fellow SVU castmate Mariska Hargitay, who’s played Detective (now Captain) Olivia Benson for 24 seasons (and counting).

Belzer will drop to Number 3 on this list if his fellow SVU actor Ice-T returns as Detective (now Sergeant) Odafin Tutuola in this program’s 25th season. NBC, I hasten to add, has yet to renew SVU, already the longest-running primetime drama in the history of American television, for its 25th season, although betting against this prospect seems like a fool’s errand given this second Law & Order series’s popularity.

Plus, Belzer lays claim to another American-television record, having appeared as Munch on five other one-hour drama series (Chris Carter’s The X-Files, Tom Fontana’s The Beat, David Simon’s The Wire, and Dick Wolf’s Law & Order and Law & Order: Trial by Jury), two half-hour comedy series (Tina Fey’s 30 Rock and Mitchell Hurwitz’s Arrested Development), one half-hour animated series (Seth MacFarlane’s, Mike Barker’s, and Matt Weitzman’s American Dad!), and a late-night talk show (namely, a comedy sketch performed on the 7 October 2009 episode of Jimmy Kimmel Live!).

Belzer, in simpler language, appeared as the same character on 11 different American television programs, a record that may never be broken. His prolificacy in this role is perhaps the most notable aspect of a career that stretched over five decades, beginning in 1972 and ending when Belzer left public life after departing SVU for good in 2016. Working as a stand-up comedian, a part-time conspiracy theorist, and the author (or co-author) of six books (including the cheekily titled 2008 novel I Am Not a Cop!), Belzer was indefatigable throughout 44 years of excellent work, slowing down only after retiring to his home in Beaulieu-sur-Mer, France in 2016.

If, as reported by novelist, comedy writer, and close friend Bill Scheft, Belzer’s last words were indeed “Fuck you, motherfucker,” then he (Belzer) was just as profanely witty at the end of his life as he was for most of his 78 years on this planet.

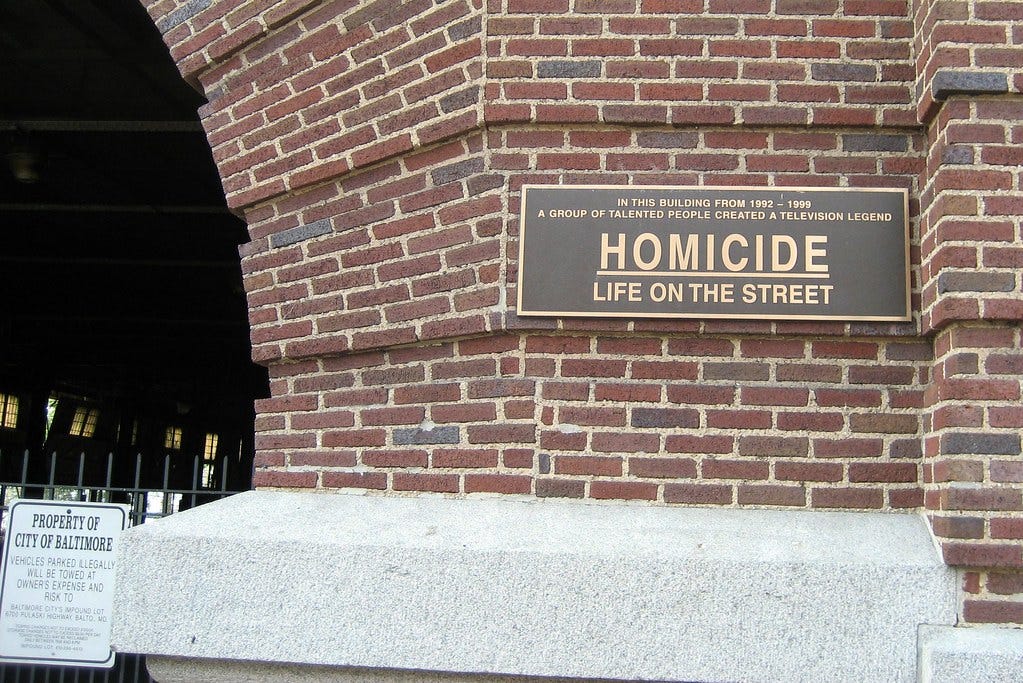

Belzer’s death provides a tragic counterpoint to the 30th anniversary of Homicide: Life on the Street’s 31 January 1993 premiere. This episode, broadcast immediately after the conclusion of Super Bowl XXVII, inaugurated a television series that remains, three decades later, a remarkable achievement for its entire cast and crew.

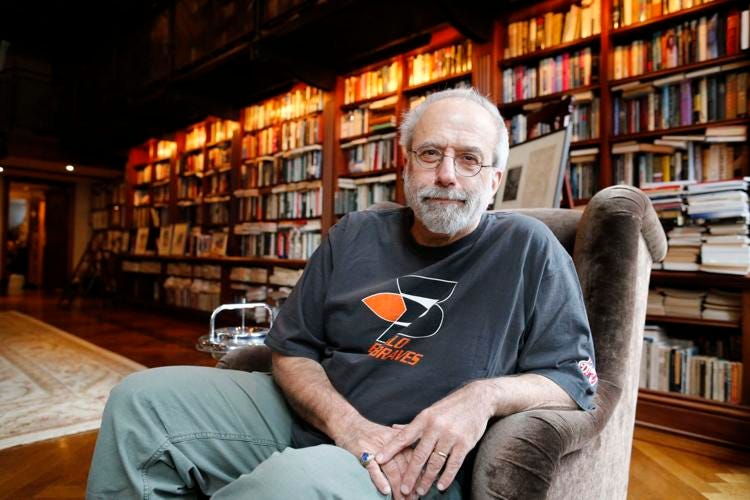

Indeed, this program is so good that I commemorate its status as an American cultural classic by reprinting “Red Balls: David Simon and Homicide: Life on the Street,” the third chapter of my 2010 scholarly monograph Violence Is Power, below. Bearing a new title and following The Vestibule’s house style, this l-oo-nnn-gggg piece analyzes how Homicide adapts David Simon’s 1991 book Homicide: A Year on the Killing Streets as well as any television program has ever transferred a work of non-fiction into a continuing, weekly drama series.

Violence Is Power compares the lives, careers, and television writing of David Simon (the creator of The Corner, The Wire, and Tremé, among others) and David Milch (the writer-producer who co-created—with the late-great Steven Bochco—1993-2005’s NYPD Blue and who created 2004-2006’s Deadwood) to argue that both men’s excursions into television drama have produced some of the most fascinating programs of the late 20th and early 21st Centuries, in the process becoming significant social realists whose efforts rank among the best popular art produced in the United States of America during their lifetimes.

So, for what I hope is every reader’s enjoyment, I now present “Red Balls and Blue Bloods.” The original chapter (including Violence Is Power’s complete bibliography and filmography), plus six other sources pertaining to Homicide: Life on the Street, are all available in the “Files” section that appears after this piece’s conclusion.

Despite disclaiming Violence Is Power’s title (I lost three “discussions” with my publisher’s marketing team after submitting a manuscript named American Savagery, which, as I argued during these “chats,” is the title of a book worth stealing from the library or the bookstore—remember bookstores, dear reader?), this volume still holds a special place in my heart because it’s one that I hope my late father would’ve approved. Although I’m unsure how much he’d have enjoyed reading any academic treatise, even one written by his son, he was a great lover of American television and, especially, American cop-and-detective shows. As such, Dad might well have disagreed with my evaluations of Simon’s and Milch’s work, but I would’ve loved debating those judgments (and watching those shows) with him.

And I would’ve enjoyed discussing these issues with Richard Belzer, had I ever been lucky enough to meet him in person, but, now that Belzer has joined the ancestors, I shall only say that he’ll be fondly remembered and greatly missed.

May he rest in perfect peace.

Homicide: Life on the Street

Created by Paul Attanasio

Based on Homicide: A Year on the Killing Streets by David Simon

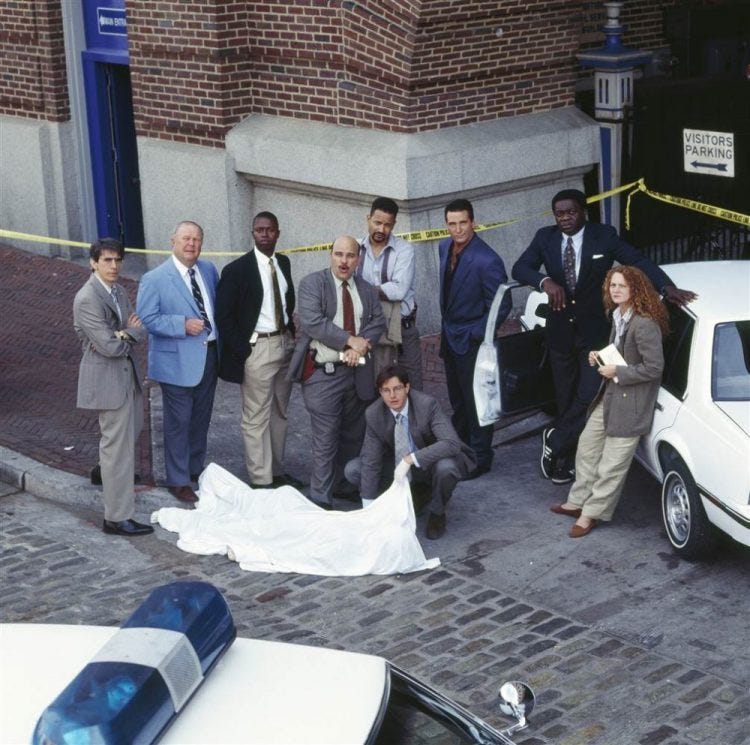

Starring Daniel Baldwin, Ned Beatty, Richard Belzer, Andre Brauger, Reed Diamond, Giancarlo Esposito, Michelle Forbes, Peter Gerety, Isabella Hofmann, Želko Ivanek, Clark Johnson, Yaphet Kotto, Melissa Leo, Toni Lewis, Michael Michele, Max Perlich, Jon Polito, Kyle Secor, Jon Seda, and Callie Thorne

Guest Starring Ami Brabson, Erik Todd Dellums, Gerald F. Gough, Wendy Hughes, Clayton LeBouef, Harlee McBride, Ellen McElduff, Walt McPherson, Austin Pendleton, Kristin Rohde, Ralph Tabakin, Judy Thornton, Sean Whitesell, and Sharon Ziman

122 one-hour episodes & 1 two-hour telefilm

Original broadcast 31 January 1993 — 21 May 1999 & 13 February 2000 (telefilm)

1. From Page to Screen

Homicide: Life on the Street (1993–1999) not only adapted David Simon’s 1991 book Homicide: A Year on the Killing Streets into a critically acclaimed television series but also inaugurated Simon’s television-writing career. Although each episode credits Paul Attanasio as this program’s creator, executive producers Barry Levinson and Tom Fontana developed Homicide: Life on the Street (hereafter known simply as Homicide) from Simon’s book once movie director Levinson optioned the rights to Homicide: A Year on the Killing Streets (hereafter referred to as A Year on the Killing Streets) soon after its 1991 publication.

Levinson—best known for directing the feature films Diner (1982), The Natural (1984), Good Morning, Vietnam (1987), and Rain Man (1988)—came to believe that the book’s rich details about the fractious professional lives of Baltimore homicide detectives deserved the narrative attention that only an ongoing series—with its multiple episodes, continuing storylines, and complex characters—could offer. Confining Simon’s 650-page book (originally pitched to Levinson as a movie) to a film’s two-hour running time would have, in Levinson’s mind, eviscerated A Year on the Killing Streets’s factual complexity, narrative density, and sociological precision.1

Levinson quickly hired Fontana, the veteran writer-producer of St. Elsewhere (1982–1988), to adapt Simon’s mammoth book into a workable dramatic program, to supervise Homicide’s writing staff, and to ensure that the series avoided cop-drama clichés. Levinson also offered Attanasio, the screenwriter who had adapted Michael Crichton’s 1993 novel Disclosure into Levinson’s 1994 film of the same title, the opportunity to write Homicide’s pilot episode after Attanasio finished the screenplay for Robert Redford’s 1994 film Quiz Show.2

Attanasio, however, didn’t function as a producer, staff writer, or consultant for the series, penning only one additional Homicide episode, “See No Evil” (2.1), during the program’s seven-season run. Critical observers, in light of these facts, more properly consider Levinson and Fontana to be Homicide’s originators. Fontana’s input became so crucial to Homicide’s success that writers-producers James Yoshimura and Eric Overmyer, in their DVD commentary for “The Documentary” (5.11), explicitly credit Fontana as the program’s creator.3

This tangled genesis, however familiar to American television, didn’t initially include Simon, who worked as a crime (or police-beat) reporter for the Baltimore Sun newspaper from 1982 until 1995. During his tenure at the Sun, Simon took two year-long leaves of absence to research and write his massively detailed accounts of urban Baltimore: 1991’s Homicide: A Year on the Killing Streets and 1997’s The Corner: A Year in the Life of an Inner-City Neighborhood. This final book was cowritten with ex-Baltimore Police Department detective Edward Burns, who would become Simon’s writing and producing partner for HBO’s 2008 miniseries adaptation of Evan Wright’s Generation Kill and, most crucially, for their HBO masterpiece The Wire (2002-2008).

Simon sold the rights to A Year on the Killing Streets but didn’t involve himself in creating, running, or supervising the program’s early seasons, even though he and David Mills co-wrote the teleplay (based on a story by Fontana) for Homicide’s second-season opener, the excellent “Bop Gun” (2.4).

This episode was broadcast by NBC, Homicide’s parent network, as the premiere of its abbreviated, four-episode second season to capitalize on guest star Robin Williams’s presence. Thanks to Levinson’s work as a well-regarded film director, he was able, in a pattern that recurred throughout Homicide’s network life, to entice big-screen actors like Williams—whom Levinson had directed to a breakout performance in Good Morning, Vietnam—and fellow movie directors like Kathryn Bigelow, Martin Campbell, Gary Fleder, and Barbara Kopple to work for the program.

Simon’s minimal involvement, however, belies his importance to Homicide’s televisual incarnation. Fontana, for one, sees A Year on the Killing Streets as decisively influential to Homicide’s success while discussing the series’s origins with Levinson during their audio commentary for its first episode, “Gone for Goode” (1.1). “I think by the end of the six years [of the program’s production] we had pretty much sucked every comma and question mark out of [David Simon’s] book,” Fontana at one point says, making an observation that no attentive viewer can deny.4

So many characters, plotlines, and criminal cases from A Year on the Killing Streets make their way into Homicide that Fontana’s cheerful hyperbole underscores how much the process of bringing Homicide to television differed from David Milch’s process in co-creating NYPD Blue (1993-2005) with Steven Bochco. Adapting Simon’s book required a fidelity to its journalistic source that Milch attempted, but could not approximate, by basing so much of NYPD Blue’s early narrative material on New York City Police Department officer Bill Clark’s detective career. This judgment doesn’t diminish Milch’s research in preparing NYPD Blue’s portrayal of urban policing, but it emphasizes how faithfully Fontana and his writers attempted to preserve the integrity of Simon’s work in their series.

Homicide: Life on the Street, in another quirk of fate, premiered eight months before NYPD Blue, although Milch and Bochco began working on their program in late 1991 or early 1992 (at roughly the same time that Levinson and Fontana began working on their series).5 Homicide, however, never matched NYPD Blue’s ratings success, mainstream popularity, or press coverage. The usual explanation for this disparity—propounded by Simon, Levinson, Fontana, Yoshimura, Overmyer, other Homicide production personnel, fans, and critics (such as John Leonard)—is that Homicide eschews car chases, gunplay, nudity, and profanity to offer a more realistic, variegated, and accurate portrayal of detective work than NYPD Blue.

Homicide, in other words, challenges its viewers’ expectations of cop shows even more than does NYPD Blue (or another contemporary drama cited for its realistic approach to the criminal-justice system, Dick Wolf’s Law & Order) to attain a level of social realism not seen in other police dramas (even Bochco’s & Michael Kozoll’s landmark 1981-1987 series Hill Street Blues).

Homicide, to be certain, is one of the best cop shows ever broadcast on American television. Only Simon’s The Wire surpasses the breadth, depth, and intricacy of Homicide’s depiction of a major American city’s urban life, while Homicide’s portrait of the complicated lives of African-American characters was, in its day, unmatched in the history of American network television. The series nicely captures A Year on the Killing Streets’s complex tone—journalistic, analytical, reflective, cynical, sardonic, and unsentimental—even as it diverges from Simon’s book by allowing its fictional detectives to indulge more abstruse musings about life, crime, religion, and love than their real-life counterparts.

2. Spinning Stories & Breaking Clichés

David Simon, whose day-to-day involvement with Homicide began during its fourth season (Simon would receive screen credit as story editor beginning in the program’s fifth season and become a full-fledged producer for Season 6), potently analyzes Homicide’s literary aspirations by stating, in “Homicide: Life in Season 4,” the behind-the-scenes documentary included in the program’s Season 4 DVD set, that, when he began writing for Homicide,

I had to put aside in my mind the characters that I saw when I was in the Homicide Unit. There were very few characters that were reflective of the real detectives I knew, which is not to say they were not completely vibrant and worthy of the drama that was written about them. They were interesting to me because I’d watched them just, consumed them like any other viewer. But they had no real connection to me, in my head, to the book characters, who were very real and a lot less philosophical.6

This assessment both credits and criticizes Homicide’s dramatization of police lives by acknowledging the program’s vivid characters while underscoring its narrative departures from the street-level reality that A Year on the Killing Streets so painstakingly documents. Simon distinguishes real-life detectives’ disinterest in questions of morality, ethics, and justice from their fictional avatars’ concern with these issues. Simon advances a seemingly sophisticated appraisal of the different parameters of journalism and television drama by recognizing how the show’s characters philosophize about their work and their lives more explicitly than the actual detectives whose experiences Simon’s book chronicles.

This perspective, however, ignores the expert pacing, nuanced characters, and precise details that A Year on the Killing Streets includes. The book masterfully integrates these techniques into its sociological evaluation of the problems besetting late 20th-Century Baltimore to erode the boundaries between neutral reportage and literary license that Simon insists set his book apart from its television counterpart. A Year on the Killing Streets, indeed, includes continuous third-person commentary that analyzes the nature of police work alongside the economic disillusionment, political lethargy, racial animus, and cultural dislocations that define Baltimore’s civic life during the late 1980s and early 1990s. Tom Fontana and Homicide’s writers, since their program rarely employs voiceover narration to advance an episode’s plot, allow their characters to verbalize ideas, concepts, and opinions that A Year on the Killing Streets presents as the work of a single, unnamed, third-person narrator (who seemingly reflects Simon’s attitudes, opinions, and perspectives).

Simon, in the same behind-the-scenes interview, elaborates how Homicide’s detectives diverge from the men and women whom he observed during his year-long sojourn with the Baltimore Police Department’s Homicide Unit:

There was not a lot of great debate about religion or good or evil. The nature of good and evil was determined based on “I have enough to charge or I don’t have enough to charge” or “he’s an asshole or he’s not an asshole.” That struck me as the difference in the show, between the show and the book is that, uh, the show really was, like, trying to tackle some great moral questions through the use of character, and real life often isn’t like that.7

This assessment invokes an implicit dichotomy between A Year on the Killing Streets’s putative realism and Homicide’s moral drama. Ethical concerns arising from murder cases, in Simon’s telling, do not plague actual detectives. Real-life homicide cops—or “murder police,” in Baltimore parlance—focus on a case’s essential details rather than becoming emotionally, spiritually, or intellectually invested in a heinous act whose motives, Simon implies, they try not to ponder.

Such philosophizing amounts to reckless folly for people whose task is closing murder cases, not comforting the family members of homicide victims, even if determining who committed the crime, arresting the perpetrator(s), and relinquishing the suspect(s) to the criminal-court system helps these family members manage their grief. The emotionally draining experience of probing murder, in other words, requires homicide detectives to reduce their field of vision to a case’s details. This reaction is a psychological defense against the sadness, anxiety, and depression that contemplating the tragedy of murder might induce.

Indeed, homicide detectives’ impulse to judge their job performance by tracking which cases result in arrests rather than indictments or convictions typifies A Year on the Killing Streets’s depiction of late 20th-Century urban American policing as a bureaucratic morass that sporadically, if ever, seeks justice as its goal. Two notable passages speak to the heartless statistical ballet that Baltimore’s homicide detectives must dance to please their superior officers.

The first excerpt alternates sacred diction with profane imagery to make this point: “It is the unrepentant worship of statistics that forms the true orthodoxy of any modern police department. Captains become majors who become colonels who become deputies when the numbers stay sweet; the command staff backs up on itself like a bad stretch of sewer pipe when they don’t.”8 Homicide detectives may refuse to debate the merits of individual murders, but Simon’s account stresses how pursuing higher clearance rates subordinates all talk of good and evil to the utilitarian demands of bureaucratic authority, which co-opts religious language to demand that police officers venerate a new master: cold, hard numbers that permit no sentiment other than success (as defined by the higher-ups who control that same bureaucracy).

The second passage remorselessly punctures the hope—sustained, if not created, by the hundreds of television cop shows broadcast by American radio and television networks since the 1940s—that homicide detectives wish to do right by murder victims: “Consider the fact that a case is regarded to be cleared whether it arrives at the grand jury or not. As long as someone is locked up—whether for a week or a month or a lifetime—that murder is down.”9

This single sentence demolishes the image of virtuous detectives crusading for justice, while the following lines underscore the officious mentality that creates this heartless system: “If the charges are dropped at the arraignment for lack of evidence, if the grand jury refuses to indict, if the prosecutor decides to dismiss the case or place it on the inactive, or stet, docket, that murder is nonetheless carried on the books as a solved crime. Detectives have a tag line for such paper clearances: Stet ’em and forget ’em.”10 Closing homicide cases is, A Year on the Killing Streets repeatedly argues, less a matter of righteous indignation than a procedurally driven, paperwork-laden, and administratively burdensome occupation that, like so many careers in postindustrial America, diminishes authentic human feeling to the point that all decisions seem soulless.

This jaded vision characterizes Simon’s nonfiction work, television writing, and political outlook. Homicide effectively captures this perspective, particularly in the single-minded determination of its most original and bracing character, Detective Frank Pembleton (Andre Braugher), to close cases regardless of the victim’s identity, the perpetrator’s motivations, and the police hierarchy’s interference. Pembleton’s partner, Detective Tim Bayliss (Kyle Secor), does not share Pembleton’s cold-blooded fascination with the facts of murder but instead becomes emotionally involved in cases—particularly the killings of young children—that prompt him to wonder about “the why,” meaning the reason(s) that one human being murders another.11

Homicide’s inaugural episode, along with much of its first season, follows Bayliss’s initiation into the seemingly uncaring world of homicide detectives, who jettison empathy to prevent the emotional damage that afflicts several principal characters—including Bayliss, Detective Steve Crosetti (Jon Polito), Detective Beau Felton (Daniel Baldwin), and Detective Mike Kellerman (Reed Diamond)—throughout the program’s seven seasons. Felton’s deteriorating marriage is one of Season 3’s major plotlines, while Crosetti commits suicide in “Crosetti” (3.4). Kellerman nearly shoots himself in the head in “Have a Conscience” (5.13), avoiding this fate only because his partner, Detective Meldrick Lewis (Clark Johnson), talks him out of it.

Bayliss never goes this far, but the death of Adena Watson, a young African-American girl whose murder is Bayliss’s first case as primary investigator, haunts him for Homicide’s entire broadcast run. Bayliss, in Homicide’s strongest rebuke to the cop-drama convention of closing major cases by the end of an episode, a season, or the series itself, never solves Watson’s murder.

These narrative developments parallel A Year on the Killing Streets better than Simon recognizes, while Barry Levinson’s and Tom Fontana’s commitment to civil liberties ensures that Homicide offers a more progressive portrayal of urban policing than NYPD Blue. Only the early seasons of Hill Street Blues match Homicide’s realistic depiction of urban life, although Hill Street, by setting its police station in a harsh (even animalistic) ghetto neighborhood, indulges stereotypes about the diminished, damaged, and violent lives of its district’s mostly poor, mostly non-white residents.

Homicide, thanks to Fontana’s insistence on avoiding cop-drama formulas, breaks these conventions more frequently than it obeys them, mixing elements of the traditional police procedural, the observant social comedy, and the classic drama (which Richard Clark Sterne, in his essay about NYPD Blue in Robert M. Jarvis’s & Paul R. Joseph’s invaluable academic anthology Prime Time Law: Fictional Television as Legal Narrative, believes commercial television feebly reproduces12) into a unique series whose terrific writing, documentary camera work, and superlative acting enhance its social realism.

3. Keeping It Real(?)

This final statement should not imply that Homicide is, in fact, an objective or neutral account of homicide detection. By sympathizing with its cop characters, even while presenting them unsentimentally, Homicide fails to dramatize the lives of criminals, suspects, and residents with the same careful attention that it accords police officers (only Simon’s The Wire achieves this goal).

The series, however, offers a more vibrant portrait of its urban community than any previous (or contemporary) network police drama, permitting Homicide to stand apart from the generic tradition in which it participates. Tom Fontana acknowledges this complicated lineage during an interview with James L. Longworth, Jr. in TV Creators: Conversations with America’s Top Producers of Television Drama by revealing that Levinson originally approached St. Elsewhere producers John Tinker and John Masius to adapt A Year on the Killing Streets into a television series.

When they departed the project, Tinker and Masius urged Levinson to contact Fontana. “I went out and met with Barry,” Fontana tells Longworth, “and when the whole idea of a cop show was presented to me, I was like, ‘Well, there’s never going to be a better cop show than Hill Street Blues, there’s no other way to do it better.’”13 This assessment, however, didn’t deter Levinson from outlining a different vision for his new television program: “‘I want to do a cop show without car chases and without gun battles. I want to do Homicide as a thinking man’s unit.’ And so, the minute [Levinson] said that, I [Fontana] said, ‘That’s impossible. I have to be part of this!’”14

Fontana’s enthusiasm led to him to hire writers, particularly Chicago-born playwright James Yoshimura, who would upset the accepted conventions of television crime drama, resist network pressure to make Homicide a more predictable program, and honor the spirit of Simon’s book. Fontana’s general success in this venture allows Homicide to fulfill Levinson’s aspiration for the series to become a thinking person’s police show even while indulging elements of traditional cop dramas, whether infrequent shootouts, car chases (that sometimes end with detectives crashing their squad cars into other vehicles), and onscreen violence.

Placating NBC’s desire to improve the show’s ratings occasionally forced Homicide’s writers to honor the network’s demands for more romance, more violence, and more closed cases, but these compromises demonstrate that Homicide differs from typical cop shows by stressing authenticity in tone, mood, atmosphere, pace, and procedure. The series generally avoids rushing from scene to scene, while the long conversations and interrogations that typify Homicide’s structure allow its principal characters to achieve fully rounded lives of their own.

Fontana, however, refuses to demean Homicide’s major competitor, NYPD Blue, to improve his own program’s stature. He tells Longworth, “My opinion is that David Milch and Jimmy Yoshimura are probably the two most talented people writing television today, or, at least, episodic television” (this interview was conducted before Homicide’s 1999 cancellation, although Longworth’s book was not published until 2000).15 Fontana’s invocation of Hill Street Blues’s quality and Milch’s talent demonstrates his awareness of Homicide’s antecedents and contemporaries, but his respect for Yoshimura counters charges that Homicide cannot escape the shadow of its more popular rival. “My whole attitude toward Yosh is when he comes to me with an idea that he is excited about, I would be an idiot to stand in his way,”16 Fontana comments, implicitly declaring Homicide to be just as good as NYPD Blue.

Little rivalry exists in Fontana’s mind between his and Milch’s series due to Homicide’s singular style. Not every author can master it, making Homicide a challenging, but not impossible, program to write: “In my mind, not every writer can write everything. There are a lot of incredible writers who could not write an episode of Homicide, and that doesn’t mean they’re not good writers. That just means that they’re not right for this particular show.”17

This generosity of spirit explains how David Simon became such an intelligent television dramatist, for Fontana closely mentored Simon’s transition from journalist, book author, and social critic to small-screen writer. Simon, in the “Homicide: Life in Season 4” documentary, confesses that he declined producer Gail Mutrux’s offer to write the first episode because he knew nothing about television writing: “There was a moment where Gail called me up and said, ‘Would you like to try your hand at writing the pilot?’ and, uh, like an idiot, I said, ‘You know, no, get somebody who knows what they’re doing because I’ll mess it up and there’ll be no TV show.’”18

Simon eventually left the Baltimore Sun and came aboard Homicide’s writing staff, where Fontana instructed him in the challenges, pitfalls, and pleasures of producing television. Simon praises Fontana’s tutelage in “Inside Homicide: An Interview with David Simon and James Yoshimura” (a short documentary included in Homicide’s Complete Season 5 DVD set) by explaining Fontana’s approach to making television: “Tom made a promise to me, which was, uh, he said, ‘I don’t pay as much as some producers and I don’t give titles easily—I won’t make you a producer until you’re really producing—but I’ll teach you how to do this, I’ll teach you everything I can possibly teach you about not just writing for television, but protecting the writing,’ which is what producing is in a sense.”19 Simon recognizes that Fontana’s concern for preserving the integrity of every writer’s story distinguishes television from cinema: “The writer has no authority to protect his story, his telling of the story, in features. It’s, it’s a director-and star-based medium, but in television, the writer rules.”20

Simon would take this final dictum to heart when creating, producing, and writing The Corner and The Wire, but, despite Simon’s status as the author of A Year on the Killing Streets, his first television job required him to work as one member of Homicide’s busy writing staff under Fontana’s supervision. This arrangement benefited Simon by allowing him to learn the rigors of producing a weekly series, to recognize the limitations that major American networks impose upon their primetime dramas, to negotiate the resulting narrative constrictions, and to appreciate the unique possibilities that fiction affords socially conscious authors when constructing incisive, relevant, and realistic stories about crime, race, class, and politics.

“Homicide: Life in Season 4” reveals that Fontana dubbed Simon “Nonfiction Boy” because Simon initially approached writing Homicide with a journalist’s eye for accuracy. His talent for lucid detail explains how A Year on the Killing Streets’s exacting portrait of urban police work enriched Homicide’s early seasons by providing Fontana and his writers with exhaustive material that they could fashion into inventive, unconventional, and quirky crime drama.

Simon, once he joined the writing staff, “was always the guy at the meeting that went, ‘Well, it really wouldn’t work that way,’”21 but this perspective misunderstands the power of television drama. Homicide, by emphasizing, altering, and enhancing Simon’s account of real-life murder police, sketches a more viscerally intimate portrait of fictional events than A Year on the Killing Streets does with its journalistic (and supposedly detached) tone. Homicide’s signature visual style of handheld footage, jump cuts, and quick montage may approximate the vérité storytelling of documentary films, while A Year on the Killing Streets’s fulsome details may create a comprehensively realized world, but Homicide’s lively characters, compelling stories, and handsome production values ensure that its audience relates to its imaginary portrait of Baltimore more immediately, more incisively, and more intensely than to the book’s factual accounts of urban crime.

Fontana, because he understood these differences, ably honed Simon’s dramatic instincts while taking advantage of Simon’s vast knowledge of police culture to meld fact with fiction, to generate Homicide’s distinctive style, and to teach Simon how powerful a medium television can be. Simon, in the “Inside Homicide” documentary, lauds Fontana’s willingness to consider his (Simon’s) desire for accuracy: “Tom, to his credit, he would listen and . . . sometimes he would say, ‘Okay, well, let’s do it the way it really would be’ and, other times, he would say, ‘No, this is better storytelling. You know, let’s do the make-believe here because this makes a better episode.’ And the purposes were different, you know. It wasn’t journalism. It was episodic drama.”22

This formulation’s invocation of “make believe” concedes that television drama’s fictional imperatives—rather than always promulgating tired, hackneyed, and formulaic stories—can, at their best, submerge viewers into an invented environment that offers stunning appraisals of everyday life. Homicide, in other words, may not be journalism, but its documentary tone permits Fontana, Simon, and the program’s other writers to fashion a cop show that is also an absorbing and compelling, yet sometimes imperfect, work of social realism.

4. Cop Shops & Stops

The dichotomy between journalistic accuracy and televisual imagination suggested by David Simon’s comments is, in at least one significant respect, false. Simon implies that his book’s account of one year (1988) in the life of the Baltimore Homicide Unit reports the events he observed more clinically than Homicide’s fictional narrative. Yet, as Christopher P. Wilson notes in “True and True(r) Crime: Cop Shops and Crime Scenes in the 1980s,” his masterful analysis of three popular true-crime books published in the early 1990s (Simon’s A Year on the Killing Streets, Mitch Gelman’s 1992 Crime Scene: On the Streets with a Rookie Police Reporter, and Robert Blau’s 1993 The Cop Shop: True Crime on the Streets of Chicago), this presumption elides the social, political, economic, and ideological biases that influence how A Year on the Killing Streets represents late 20th-Century urban policing.

Simon’s book may construct a dispassionate, even neutral, façade, but this impression cannot long withstand critical analysis. Wilson identifies A Year on the Killing Streets as an exemplary “‘liberal-realist’ initiation narrative,” or a story of “baptism into an urban, street-smart wisdom” that, despite its liberal credentials, participates in the “‘authoritarian populism’ or ‘popular conservatism’ emergent in the 1980s.”23 Simon’s cop-shop narrative, like Gelman’s and Blau’s books, proclaims its neutrality while replaying a “dramatic 1980s clash of posts and dispositions: the encounter of young liberal reporters, in the twilight years of Reagan-Bush America, with the supposed pathology of our inner cities.”24

Wilson perceptively argues that true-crime (or cop-shop) books such as A Year on the Killing Streets advance a specific view of American crime, namely, a hard-boiled perspective that “might well be described as working in the field of urban ‘police populism.’”25 These books represent police power as necessary to preserving social order; claim sympathy for impoverished citizens who live in crime-infested areas, but rarely deal with the institutional, structural, and social reasons that poverty and crime exist; and see criminals as social deviants who fail to follow civilized rules, not as complex human beings trapped in an unjust system.

They offer “a terribly unrepresentative look at American violence” because, as a “murder-based genre,” the true-crime narrative “overemphasizes female victims, older victims, and—intriguingly—white offenders and white victims” while reproducing Vance Thompson’s compelling insight that “the police reporter’s daily lesson is ‘the fall of man.’”26 The true-crime book’s tendency to regard police work as a notable (even noble) effort to preserve order, in other words, compromises true crime’s much-celebrated courage in facing urban America’s bitter realities. Critical readers, therefore, should notice how A Year on the Killing Streets adopts law enforcement’s Manichean view of its task as defending civilization from the chaos originating in faceless, forbidding, and frustrating American cities that threaten to spin out of control at any moment.

Simon’s mammoth book, to its many admirers, is a masterpiece of field research, vigilant observation, and critical analysis that confronts uncomfortable truths about race, class, politics, and crime in late 20th-Century urban America. Wilson’s article, however, reminds Simon’s audience that A Year on the Killing Streets is not the objective account that the author’s comments about the differences between book and television claim to be. This judgment can neither diminish Simon’s superlative writing in A Year on the Killing Streets nor dismiss its extensive study of American policing because the book’s literary fineness is as impressive as its vivid reportage. Simon, simply stated, is a gifted author whose control of language, theme, symbol, and pace gives A Year on the Killing Streets a novelistic quality that predicts his attentive, elegant, and darkly humorous television writing.

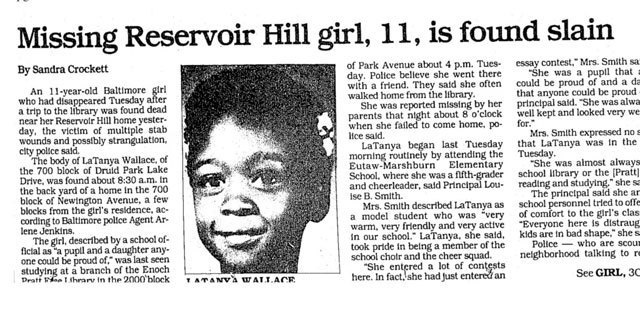

Perhaps the best example of how the book fuses journalism, social conscience, literary prose, and police populism is the section that recounts the discovery of the corpse of LaTanya (sometimes spelled as La-Tonya or Latonya) Kim Wallace, an 11-year-old African-American girl dumped in a Baltimore alleyway after being molested, strangled, and disemboweled:

It is the illusion of tears and nothing more, the rainwater that collects in small beads and runs to the hollows of her face. The dark brown eyes are fixed wide, staring across wet pavement; jet black braids of hair surround the deep brown skin, high cheekbones and a pert, upturned nose. The lips are parted and curled in a slight, vague frown. She is beautiful, even now. . . .

Among the detectives and patrol officers crowded over the body of Latonya Kim Wallace there is no easy banter, no coarse exchange of cop humor or time-worn indifference. Jay Landsman offers only clinical, declarative statements as he moves through the scene. Tom Pellegrini stands mute in the light rain, sketching the surroundings on a damp notebook page. Behind them, against the rear wall of a rowhouse, leans one of the first Central District officers to arrive at the scene, one hand on his gun belt, the other absently holding his radio mike.

“Cold,” he says, almost to himself.

From the moment of discovery, Latonya Wallace is never regarded as anything less than a true victim, innocent as few of those murdered in this city ever are. A child, a fifth-grader, has been used and discarded, a monstrous sacrifice to an unmistakable evil.27

This passage emblematizes Simon’s authorial talent by offering lucid sensory details that re-create Wallace’s murder scene yet emphasize its emotional aridity by underscoring the near silence that overtakes the assembled officers and detectives. Simon reverses his reader’s expectations by noting how the detectives refuse the gallows humor that characterizes every previous crime scene that A Year on the Killing Streets records. The passage’s richness of detail contrasts with its starkness of feeling to prepare the reader for the final paragraph’s moralizing conclusion. Mentioning monstrosity, sacrifice, and evil reveals the suppressed horror that the officers and narrator feel but do not verbally express.

Identifying Wallace as a “true victim” purer than most murdered people, whom the killer has treated as garbage, transforms the girl into an angelic symbol while juxtaposing good and evil so effectively that Pellegrini, the primary investigator, must now avenge Wallace’s death if he wishes to right this hideous wrong. The police, as this excerpt concludes, no longer serve as simple investigators but rather as populist defenders of the city’s vulnerable children, meaning that they become metaphysical defenders of innocence itself.

This passage also substantiates Christopher P. Wilson’s point that A Year on the Killing Streets cannot reproduce true journalism’s impartiality. Simon synthesizes clinical observation with moral passion to represent the homicide detective, in true cop-shop fashion, as what Wilson calls “a dedicated, hardbitten knight of the city”28 who seeks truth, pursues justice, and bears witness for defenseless victims. Depicting homicide detectives in this fashion positions Simon’s book as an exemplary cop-shop narrative that exhibits “a long-recognized double-edged potential in populist ideology . . . that [is] progressive and reactionary, liberal and authoritarian all at once.”29

Such contrary motives lead Simon to merge dispassionate observation, righteous indignation, and conscientious police work into a powerful vignette that dismantles all claims to objectivity. The Wallace murder—fictionalized in Homicide as the never-closed Adena Watson case—is the book’s primary example of a red-ball investigation, or, as Simon baldly defines this term, “murders that matter.”30 Although homicide detectives may repudiate caring about motive or morality, their practiced world-weariness extends only so far. The emotional attrition of working as murder police, therefore, requires detachment, dark humor, and defensive cynicism. The homicide detective, according to Simon’s book, “gives what he can afford to give and no more” by “carefully measur[ing] out the required amount of energy and emotion” before he “closes the file and moves on to the next call.”31 For the best investigators, however, this dispassion never becomes psychological numbness.

This sympathetic portrait of homicide detectives proves that A Year on the Killing Streets, far from offering a neutral account of their grim work, weaves symbols, themes, and tropes about justice, morality, and religion throughout its narrative, bringing it closer to Homicide’s imaginary portrait of Baltimore than Simon may care to admit. The television series, indeed, reproduces the book’s tone better than Simon recognizes, so much so that most episodes disrupt the documentary approach that Barry Levinson creates in “Gone for Goode” with flashbacks, surreal images, musical montages, and repeated scenes. Homicide develops into a faithful adaptation of A Year on the Killing Streets that, by employing stylized visual, aural, and storytelling strategies to modulate the program’s sharp dialogue, naturalistic performances, and realistic settings, combines imaginative extrapolation with memorable imagery to produce an artistic work that reflects, even as it transcends, reality.

5. Three Men & A Meeting

David Simon, in fact, masters these narrative techniques during his tenure at Homicide thanks to Tom Fontana’s guidance. Simon’s participation in writing five noteworthy Homicide episodes best illustrates his flair for melding fact, fantasy, and fiction into compelling episodic drama while predicting the excellent television that he will create after Homicide ceases production. Examining “Bop Gun” (2.4), “Bad Medicine” (5.4), Parts 2 and 3 of “Blood Ties” (6.2 and 6.3), and “Sideshow (Part 2)” (7.15) in light of Fontana’s Emmy-winning script for “Three Men and Adena” (1.6) demonstrates the storytelling gifts that permit Simon to craft The Corner’s unflinching depiction of inner-city drug addiction and The Wire’s unparalleled portrait of urban decline.

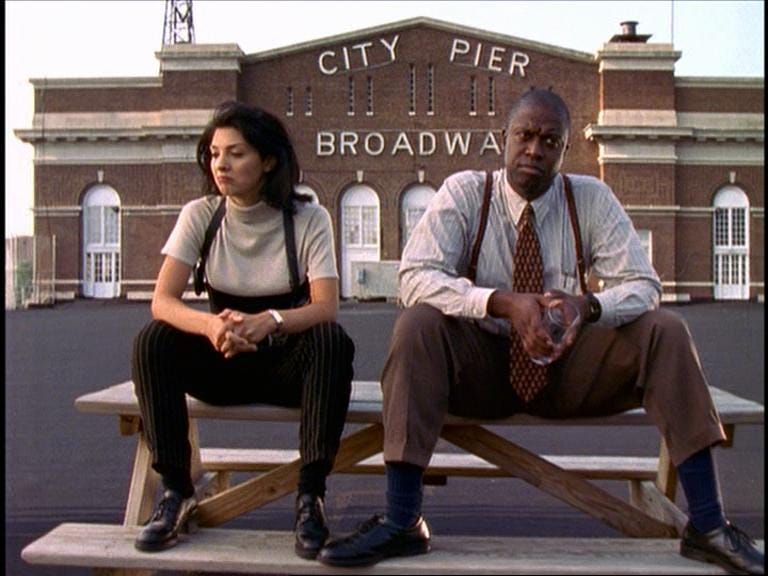

“Three Men and Adena” may be Homicide’s best-known and best-reviewed episode.32 The story takes place almost entirely in “The Box,” the Homicide Unit’s stark, functional, and unattractive interrogation room. Detectives Bayliss and Pembleton interrogate Risley Tucker (Moses Gunn), Bayliss’s prime suspect in Adena Watson’s murder, for 12 hours to elicit a confession. Tucker, an “Arabber” who sells fruits and vegetables from a horse-drawn cart that roams Baltimore’s many neighborhoods (a nomadic existence that marks Tucker as untrustworthy in the eyes of many residents, including Adena’s mother), has been interrogated on two previous occasions, making this third attempt the final time that Bayliss and Pembleton can legally question him.

“Three Men and Adena” adapts a relatively short passage from A Year on the Killing Streets into a remarkable hour of television that is, as John Leonard notes in Theodore Bogosian’s excellent documentary Anatomy of a “Homicide: Life on the Street,” a masterpiece of writing, setting, and acting that exceeds “Ariel Dorfman’s Death and the Maiden . . . and a number of Don DeLillo novels about what happens to men in small rooms.”33 Simon’s book recounts how detectives Tom Pellegrini and Harry Edgerton question a suspect called “The Fish Man, as he has long been known in the neighborhood,” a “fifty-one-year-old living alone in a second-floor apartment across the street from his [fish] store” and a “grizzled, time-worn piece of work [who] was quite friendly with Latonya [Kim Wallace]—a little too friendly, as far as the child’s family was concerned.”34

“Three Men and Adena” transforms the Fish Man into Arabber Risley Tucker to dramatize the fissures of race, class, age, and gender that crime drama frequently portrays but rarely interrogates as maturely as Fontana’s script does. This episode allows Tucker, after enduring alternately respectful, scornful, friendly, and angry questioning by Bayliss and Pembleton, to reverse the interrogation’s dynamic by articulating the emotional baggage that defines both detectives. Tucker calls Pembleton a member of the “Five Hundreds,” or a successful and professional Black man who condescends to working-class “colored folk” such as Tucker, before accusing Pembleton of hating himself for chasing “the white dream” rather than authentically connecting with his racial roots.

Tucker also verbally attacks Bayliss by comparing him to the white plantation owners who raped enslaved women, claiming that Bayliss not only carries a darkness inside himself that terrifies the detective but also fears being perceived as an amateur by his colleagues. Tucker, in a long monologue, then mournfully tells both detectives how he (Tucker) talked with Adena as often as possible, how he noticed the small details of her behavior, and how he came to adore her. Tucker weeps, finally confessing that, to the profound shame of a man in his sixties, “the one great love of my life was an 11-year-old girl.” Tucker, however, never admits to killing Adena. The episode concludes with Pembleton certain that Tucker murdered Adena, Bayliss unsure about this possibility, and Tucker watching the squad room’s television before being set free.

Fontana’s rich, provocative, and perceptive script questions the possibility that homicide detectives can conclusively determine the truth during any investigation. As Richard Clark Sterne argues when comparing “Three Men and Adena” to NYPD Blue’s more conventional interrogation scenes, Fontana’s Homicide episode “evokes with an insight rare in television fiction mutual tensions and distrust” between African Americans and police departments “that can militate against the establishment of ‘the facts’ in a police interrogation.”35 Tucker’s ability to recognize the inner doubts, fears, and inadequacies that afflict Pembleton and Bayliss reflects a street vendor’s talent for observing people, while Tucker’s success at undermining the self-assured demeanor of even so confident a character as Pembleton illustrates how uncertain a venture investigating homicide cases is.

Although Pellegrini’s and Edgerton’s questioning of the Fish Man doesn’t see this lonely, middle-aged store owner take control of the interrogation in the same way that Tucker does in “Three Men and Adena,” Fontana’s episode illuminates two important truths about police work that A Year on the Killing Streets also emphasizes. The first lesson may surprise viewers accustomed to the cop-drama convention of crack detectives pursuing every possible lead en route to solving each week’s case: “Even with the murders themselves,” Simon writes, “much of what clears a case amounts to pure chance.”36 The second lesson involves the “detective’s Holy Trinity, which states that three things solve crimes: Physical evidence. Witnesses. Confessions.”37

Fontana’s script incisively dramatizes each element by depicting a long interrogation in which Bayliss and Pembleton offer so much physical evidence against Tucker that the viewer initially takes this information to be overwhelming. The moment when Pembleton rips a map (of the neighborhood where Adena’s body was discovered) off the wall to reveal grisly photos of her mutilated corpse is especially effective. Tucker, however, is neither as shocked nor as saddened as Bayliss hopes, thereby diminishing Bayliss’s attempt to force him to recognize just how horrific Adena’s death is.

Tucker never confesses to murder but, by revealing his shameful love for the young girl, demonstrates why, according to A Year on the Killing Streets, “the detective’s trinity ignores motivation, which matters little to most investigations. The best work of Dashiell Hammett and Agatha Christie”—to say nothing of police dramas such as Hill Street Blues, NYPD Blue, and Law & Order—“argues that to track a murderer, the motive must first be established; in Baltimore, if not on the Orient Express, a known motive can be interesting, even helpful, yet it is often beside the point.”38

“Three Men and Adena” exposes Tucker’s reason for consenting to a third interrogation as his twisted need to purge the pedophiliac feelings he holds for Adena. This unexpectedly tragic motive fails to secure a confession that justifies Bayliss’s frenzied work on the case, Pembleton’s belief in Tucker’s guilt, or the viewer’s expectation that the episode will see justice done by tricking Tucker into admitting his complicity in butchering a child. “Three Men and Adena,” thanks to Fontana’s firm control of all dramatic elements, even invalidates the Year on the Killing Streets passage that summarily dismisses the significance of determining a killer’s motive: “Fuck the why, a detective will tell you; find out the how, and nine times out of ten it’ll give you the who.”39

Bayliss and Pembleton know how the girl was murdered, but this information cannot tell them who committed the crime despite their best suspicions. Bayliss’s misgivings about Tucker’s culpability mark the episode’s final statement about the ambiguity of establishing guilt and innocence. “Three Men and Adena” smartly upends the expectations of its genre and its source material to undermine the efficacy of the investigative methods that Simon’s authoritative book recounts.

This accomplishment illustrates the capacity of skillful television drama to challenge its viewer’s preconceptions. Fontana’s script, beyond inspiring Andre Braugher, Kyle Secor, and Moses Gunn to deliver extraordinary performances, also sets a pattern for Homicide’s writers (including Simon) to follow. Simon’s best scripts for the program capture police work’s frequently disappointing realities while indulging the artistic liberties, strategies, and techniques unique to episodic television drama.

6. Gunning for Cover

David Simon’s first Homicide: Life on the Street episode, “Bop Gun” (2.4), written in collaboration with David Mills and based on a story by Tom Fontana, displays Homicide’s penchant for musical montage, crosscutting, and realistic portrayals of homicide detectives’ indifference to the crimes they investigate.40 Iowa tourist Catherine Ellison is murdered when three young men rob her, her husband Robert (Robin Williams), and her two children, Abby (Julia Devin) and Matt (Jake Gyllenhaal), at gunpoint. Catherine refuses to relinquish a golden locket, then receives a fatal gunshot that sets the story’s emotional dynamic into motion.

The episode’s teaser (the sequence that precedes its opening credits) is a terrific montage that intercuts images of the Ellisons enjoying a walking tour of Baltimore’s sights (including Camden Yards) while consulting a guidebook; of three young men—Vaughn Perkins (Lloyd Goodman), Marvin (Antonio D. Charity), and Tweety (Vincent Miller)—playing basketball in an alleyway until Marvin brandishes a .45 pistol; and of detectives Beau Felton (Daniel Baldwin) and Kay Howard (Melissa Leo) going about their daily routine while Seal’s song “Killer” plays over the soundtrack.

When Perkins, Marvin, and Tweety see the Ellisons walking down a street, still looking for tourist spots, the men, clearly intending to rob the family, move toward them. “Bop Gun” follows Robert Ellison as he gives Felton and Howard information about the crime, makes arrangements for his wife’s remains to be returned to Iowa, comforts his children, and expresses shame at being too afraid to intervene during the robbery. Felton, Howard, Tim Bayliss, and Meldrick Lewis eventually arrest, interrogate, and charge Tweety, Marvin, and Perkins, but even Perkins’s conviction cannot relieve the anger, confusion, and grief that Robert Ellison experiences.

The episode’s signature scene comes when Ellison overhears Felton, Howard, and Detective John Munch (Richard Belzer) joking about how Ellison described the gun that shot Catherine as “big and metal.” When Felton enthusiastically remarks, “I am telling you, I am going to rack up the overtime on this one” (the case has become an instant red ball because it involves a tourist’s death), Ellison demands that Felton be removed from the investigation.

Lieutenant Al Giardello (Yaphet Kotto), Homicide’s shift commander and Felton’s superior officer, explains his detective’s seemingly cold attitude to Ellison: “A few weeks ago, he was working on a father of four shot in East Baltimore. After that, a domestic stabbing and, after that, a drug shooting in a project where an innocent bystander was killed. And next week, it will be somebody else. He’s not going to feel what you feel. None of us are.” Ellison comments that Giardello is not as insensitive as Felton, causing the lieutenant to say, “Mr. Ellison, I can still remember the first murder I ever handled. . . . I can’t remember my fiftieth or my fortieth. None of us can. But the only difference between Felton and the rest of us is that he doesn’t have the patience to hide that fact. You need him to solve your murder, not to grieve.”

This unsentimental dialogue reflects A Year on the Killing Streets’s casual attitude toward homicide. David Simon, in Theodore Bogosian’s documentary Anatomy of a “Homicide: Life on the Street,” stresses this scene’s authenticity by noting that Felton’s overtime comment is “a conversation that would happen. It would happen in any homicide unit anywhere in America, and when I saw it actually being acted out, I, I got a real kick in the pants because I thought, ‘Wherever they are, homicide cops are watching this and they’re cracking up ’cause they know how true it is.’”

Williams’s, Baldwin’s, and Kotto’s excellent performances enhance the moment’s realism, while Ellison’s grief—he later cries while clutching his wife’s nightgown—adds an emotional poignancy that counteracts Felton’s unfeeling attitude. The fact that Ellison’s children, lying in bed in the next room, hear him weep transforms “Bop Gun” into a touching, resonant, and accurate portrait of human anguish. Simon and Mills don’t downplay the family’s sadness but allow Felton’s insensitivity to cast the Ellisons’ heartache into even greater relief.

“Bop Gun” employs visual and aural techniques whose narrative effects A Year on the Killing Streets cannot replicate. The teaser resembles a music video, but juxtaposing the disparate behavior of the unsuspecting Ellisons, the initially jovial yet larcenous basketball players, and the seen-it-all-before banter between Felton and Howard foreshadows how these people’s lives will violently intersect before underscoring how tenuous human life, freedom, and safety are. The episode repeats this opening sequence’s parallel editing during Marvin’s and Tweety’s dual interrogations. While Felton and Lewis question Marvin in The Box, Howard and Detective Stanley Bolander (Ned Beatty) grill Tweety in The Box’s observation room as Public Enemy’s “Get Off My Back” provides the scene’s dialogue.

Rather than resorting to the longer, more deliberate interrogations that characterize other Homicide episodes and Simon’s A Year on the Killing Streets, this short montage adroitly intercuts Marvin’s and Tweety’s interviews to demonstrate how homicide detectives play suspects against one another, how they upset each man’s intellectual equilibrium, and how they exhaust each arrestee’s emotional endurance. The sequence’s brevity distorts the actual time such interrogations require, yet emphasizes their inherent unpleasantness. An agitated Tweety eventually offers information despite Marvin remaining stoic, with Tweety mentioning that Vaughn Perkins was provoked by Catherine Ellison’s refusal to hand over her locket. This statement culminates a frenetic scene whose jump cuts reflect the intensity that Tweety and Marvin experience while under interrogation.

“Bop Gun” also deals with issues of race and justice. Giardello asks Kay Howard, a detective with a perfect case-clearance rate, to look into the Ellison investigation because its implications trouble him. When Giardello doubts that his superiors would demand results if the victim were a Black Baltimore woman rather than a white female tourist, the episode briefly (but effectively) acknowledges the regrettable truth that American society privileges homicide victims based on their racial and socioeconomic background. Giardello’s statements lead Howard to observe Perkins’s interrogation, in which Perkins seems genuinely remorseful, even asking to write a letter of apology to Robert Ellison.

Based on this behavior, Howard wonders whether Perkins truly shot Catherine Ellison or whether he is confessing to the crime to protect Marvin from prosecution. Simon and Mills, in a further example of Homicide’s penchant for telling ambiguous crime stories, never resolve Howard’s doubts. When she visits Perkins in prison, he, having converted to Islam, claims the Ellison shooting as his own. Howard, although she agrees with Felton when he says that she should never have distrusted Perkins’s guilt, seems uncertain about this prospect. Melissa Leo’s carefully modulated acting throughout “Bop Gun,” particularly in Howard’s final scene with Perkins, stresses the ambivalence that haunts police detectives when determining guilt and innocence. Simon’s contributions to this episode give it an authentic sense of procedure, atmosphere, and tone that exposes the emotional, intellectual, and legal complexities that confront homicide detectives charged with conducting murder investigations.

7. The Bad & The Bard

“Bad Medicine” (5.4), by contrast, features a more self-consciously literary style.41 Simon’s script for this episode, based on a story by Tom Fontana and Julie Martin, sees Meldrick Lewis team with Terri Stivers (Toni Lewis), a narcotics detective investigating several deaths that result from people snorting, shooting, or smoking impure heroin. The victims, in a small but important detail, belong to all gender, racial, and socioeconomic groups, reflecting the tragic reality of Baltimore’s drug abuse. Simon, indeed, bases this storyline on several actual Baltimore deaths caused by ingesting heroin laced with the alkaloid drug scopolamine.42

Lewis and Stivers connect this bad heroin to Luther Mahoney (Erik Todd Dellums), a man they suspect of being one of the city’s most prominent drug moguls. Mahoney, first encountered by Lewis and Mike Kellerman in “The Damage Done” (4.19), works as a community activist and philanthropist to cover his illegal activities. Mahoney becomes a recurring nemesis for the Homicide Unit throughout Season Five, but “Bad Medicine” showcases his charm, intelligence, and unflappability.

Dellums plays the role with cultured menace, particularly when Lewis and Stivers interrogate Mahoney about the killings of two low-level drug dealers named Bo-Jack Reed and Carlton Phipps. The detectives suspect that Mahoney has ordered these slayings, so Stivers invites him to the squad room for a chat. Mahoney arrives in an expensive sports-utility vehicle wearing upscale clothing, only to find himself handcuffed to The Box’s table. Mahoney, however, willingly participates in the interrogation, condescending to Lewis and Stivers by playing along with them in a scene that captures Simon’s talent for good dialogue. Lewis begins by saying that a witness has identified Mahoney as the man behind the murders.

MAHONEY. Are you suggesting a motive?

LEWIS. Well, we have, uh, say, your theoretical drug slinger and, you know, he’s marketing a viable product, proper purity, proper cut, until some no-name, know-nothing, old-school, just-out-of-Jessup knucklehead starts messing around with his home chemistry set and he starts killing off the customers quick.

STIVERS. As opposed to killing them slow.

LEWIS. Even if this drug slinger—this theoretical drug slinger—was, was a reasonable man, I mean, your guy might be compelled to act.

MAHONEY. You know, your case makes sense. I like it.

LEWIS. I like it, too.

MAHONEY. Except I don’t sling bags and I didn’t kill Bo-Jack Reed.

STIVERS. Then who did?

MAHONEY. A guy named Carlton Phipps.

LEWIS. No, he’s dead, too.

MAHONEY. You know, I heard that.

LEWIS (sighs). See, our problem is that we don’t have any way of connecting Carlton Phipps with the murder of Bo-Jack Reed. (Mahoney raises his hand and shrugs.) Well, see, I worked that case. I talked to Carlton’s people. You know what they told me? They said that he was despondent, that he may even have taken his own life.

MAHONEY. He killed himself? He shot himself in the back of the head? Who are you fooling? He was murdered. Bo-Jack’s people came back on him. I mean, he had the gun that killed Bo-Jack right on the table—(Mahoney stops, realizing he’s given away too much.)

LEWIS (laughs). Let me ask you this: How you know where Carlton caught that bullet? And let me ask you this: How in the hell’d you know what was on the table in front of the man?

MAHONEY. Well, the word was all over about what happened to Carlton.

LEWIS (laughs as he and Stivers move to exit). Oh, Luther, Luther, Luther, you just fell for the oldest trick we got, baby.

MAHONEY. I want a lawyer.

LEWIS. I bet you do.

This interrogation initially parallels “Three Men and Adena” when Mahoney, like Risley Tucker, reverses the usual dynamic by quietly taking control of the questioning. Mahoney compliments Lewis’s theory, denies involvement in the crime, and offers crucial information. Lewis’s ploy, however, becomes clear when his effusive discussion of the investigation’s problems prompts Mahoney to provide details about the crime scene never released to the public. Lewis lies to Mahoney, who realizes too late that he’s inadvertently implicated himself in Phipps’s murder. Mahoney, however, doesn’t become flustered, angry, or truculent (as so many suspects before him have when tricked into revealing their complicity in violent crimes). Mahoney says that news of Phipps’s death was common knowledge, then requests legal representation to protect his interests. The scene is an exemplary verbal sparring match that ranks among Homicide’s best interrogations, with Erik Todd Dellums and Clark Johnson delivering effective performances.

Mahoney’s calm response is justified, as Lewis and Stivers discover when they later talk with Assistant State’s Attorney (ASA) Ed Danvers (Željko Ivanek), who tells them that, since the door to Phipps’s house was unlocked before his corpse was discovered, anyone in the neighborhood could have learned the details that Lewis has withheld from press reports. Mahoney is set free the next morning, ruefully smiling as he steps into his chauffeured vehicle. This pattern repeats during much of Season Five, with the Homicide Squad suspecting Mahoney of drug-related murders for which no conclusive evidence exists. The squad’s inability to jail Mahoney reflects the difficulty of securing drug convictions, but the character himself seems preternaturally calm during almost every appearance. This fact leads David Simon, in the “Inside Homicide” documentary, to declare, “to me, honestly, the character was always a little arch, again not resembling the drug traffickers that I knew in Baltimore in any sense.”

Simon then identifies Mahoney as a Shakespearean villain whose sophisticated persona avoids stereotypical portrayals of the thuggish drug dealer, although Simon might also have compared Mahoney to the master villains that populate the mystery fiction of Sir Arthur Conan Doyle, Agatha Christie, Dashiell Hammett, and Patricia Highsmith. The apparent naturalism of “Bad Medicine” reveals itself as a literary construct that privileges Mahoney, making him more refined than the drug dealers whom Simon and Ed Burns profile in The Corner (both the book and the miniseries) and whom The Wire authentically depicts.

“Bad Medicine,” however, demonstrates how the literary strategy of giving a fictional work’s protagonists worthy adversaries offers Homicide a classical storytelling integrity that the series normally evades when striving for realistic accounts of urban police work. This episode allows Simon to extend his dramatic range by fashioning one of Homicide’s most memorable, intriguing, and complicated characters, even if Luther Mahoney is, in the end, larger than life.

8. Cry Us a River

David Simon’s work on Parts 2 and 3 of “Blood Ties” combines his skillful characterization, fluid dialogue, and political savvy into episodes of rare power. These final two segments of the three-part storyline that opens Homicide’s sixth season (based on stories by Tom Fontana, Julie Martin, and James Yoshimura) trace the racial, socioeconomic, and political ramifications of the murder of Malia Brierre, a domestic servant employed by wealthy philanthropist Felix Wilson (James Earl Jones), one of Baltimore’s most respected citizens.

Wilson, known as Fabulous Felix, has earned his fortune by mass-producing cookies, doughnuts, cupcakes, and other confections (the character is loosely based on Wallace Amos, founder of the Famous Amos cookie brand43). Brierre’s corpse is discovered in the men’s room of the Belvedere Hotel during a black-tie gala that honors Wilson’s charitable contributions to Baltimore’s African-American community. Giardello, an old friend of Wilson’s wife, Regina (Lynne Thigpen), attends the event, only to see Pembleton, the primary investigator, interrupt the proceedings to begin questioning attendees. Neither Pembleton nor Giardello considers the Wilsons or their children, Hal (Jeffrey Wright) and Thea (Ellen Bethea), to be suspects, instead professing respect for Felix Wilson’s generosity to Baltimore’s civic life.

“Blood Ties (Part 2)” (6.2) examines the racial divisions among the Homicide Unit’s squad.44 Simon’s script acknowledges its principal characters’ tangled racial feelings in three powerful scenes that illustrate how Homicide, in Thomas A. Mascaro’s words, “depict[s] not ‘The Black Man’ but a wide range of blackness among the population of black men. As with real-life racial interactions, Homicide [is] complex” by portraying “African American men who [have] the freedom to sculpt their own identities while negotiating with whites and each other as they [enforce] the law.”45

Pembleton, Homicide’s most dynamic and intelligent character, confronts three accusations from detectives Stuart Gharty (Peter Gerety) and Laura Ballard (Callie Thorne) that he protects Wilson from criminal scrutiny due to his (Pembleton’s) racial allegiance to a powerful Black man. During the first, Gharty and Ballard discuss the case while driving to the squad room after questioning Hal Wilson. Ballard—who has recently arrived in Baltimore from Seattle, Washington—says that her friends and family call Baltimore a tough town and a hard-core place, meaning that it is a Black city. Ballard disagrees with how Pembleton investigates the case, thinking that the police should obtain hair and blood samples from Felix and Hal to determine their involvement with Brierre, who had sexual intercourse not long before her murder.

Ballard then claims that Pembleton perceives suspecting the Wilsons of murder as evidence of racism, prompting Gharty to offer this blunt assessment of the Homicide Unit’s racial politics:

GHARTY. Even if Pembleton wasn’t the primary, say you caught the case. You think you could work this murder the way you want? Not a chance in hell. Giardello would still be in our faces, still maneuvering to protect Wilson and his family. All I’m saying is, you and I, we’re just working the case, just taking in the facts, trying to identify suspects, uh, through simple common sense. Giardello and Pembleton, they are covering Wilson’s ass because Wilson’s ass is the same color as theirs.

BALLARD. Okay, hold up a second.

GHARTY. It is what it is. I’m not saying that Giardello is a bad lieutenant. I’m not saying that I think Pembelton is a lousy cop, but the racial stuff on this case is right there on the table. Nobody’s talking about it, but it’s there.

This discussion highlights the perception among white detectives that Black men protect their own. Ballard’s discomfort with Gharty’s description of Giardello and Pembleton as racial “ass kissers” offers only temporary disagreement to Gharty’s statement that he and Ballard employ common sense to investigate the case while Giardello and Pembleton pursue ulterior agendas. Gharty considers his position to be neutral, but concluding that his African-American colleagues make decisions based solely on race endorses the unexamined bias that Black men place their racial loyalties above all other concerns.

Pembleton’s and Giardello’s refusal to suspect Felix and Hal may seem unusual until the viewer recalls that no physical evidence points to either man, even if determining Felix’s and Hal’s involvement with Brierre, as Ballard indicates, is a wise investigative decision that may substantiate each man’s innocence. The circumstantial case that Gharty and Ballard construct against the Wilsons, however, is flimsy, as Pembleton and Giardello later note.

Gharty also ignores two key points. Giardello’s close friendship with Regina Wilson motivates his defense of the Wilson family, while Pembleton defers to Felix more out of respect for the man’s accomplishments than his race. Pembleton, who admires Wilson’s initiative, intelligence, and compassion, praises Wilson’s charitable work in all three “Blood Ties” episodes. Pembleton cannot ignore how Wilson has overcome the humble life of an East Baltimore project child to achieve financial prominence, yet continues to maintain close ties with the city’s working-class and poor residents.

This admiration, however, contains a racial element that makes the episode’s political stance more ambivalent. The event honoring Wilson’s philanthropy acknowledges the man’s support of African-American causes, particularly education, to suggest that Pembleton cannot fully separate race from class. The scene immediately following Gharty and Ballard’s conversation, however, finds Pembleton doing exactly that while conversing with Bayliss. Pembleton claims not to lean on race, telling Bayliss that “since my first day on patrol, I’ve worked this job as hard as it can be worked. I ask no quarter, I give no quarter. When people think of Frank Pembleton, they don’t think in terms of Black or white. On the street, in The Box, on the witness stand, I come to people as a cop, a detective.”

Pembleton emphasizes that the Wilsons’ status as Black Americans doesn’t affect his investigative judgment, but Pembleton’s need to articulate this caveat illustrates his sensitivity to accusations of racial bias. Pembleton also asserts his credentials as a cop above his status as a Black American, demonstrating how nimbly Simon reflects the competing personae that Pembleton must integrate into his workplace identity as a dogged, determined, and gifted detective.

This reality underscores the double consciousness that Pembleton must negotiate as a police officer of African descent but that Bayliss, Gharty, and Ballard do not. Pembleton’s talent as an investigator never fully overcomes his racial identity, making the third scene that Simon includes in “Blood Ties (Part 2)” even more significant as a statement about preferential treatment. Giardello angrily tells Pembleton, Bayliss, Gharty, and Ballard that the Baltimore Sun’s crime reporter has learned important details about the case nearly as soon as the lieutenant has, leading Giardello to suspect that someone inside the department has leaked the information.

Pembleton distrustfully glances at Ballard, provoking an argument that reveals the fundamental grievances that each detective holds. Ballard thinks that Felix’s and Hal’s proximity to Brierre, when coupled with Brierre’s beauty, makes them suspects, but this conclusion troubles Pembleton:

PEMBLETON. Because we all know that Black men can’t control themselves when it comes to loose shoes and tight pants.

BAYLISS. Hey, Frank. Frank! No one is saying that.

BALLARD. What I’m saying is that these people—

PEMBLETON. These people?

BALLARD. Black, white, or blue, Pembleton.

PEMBLETON. So you can prove once again that you can take the nigger out of the ghetto but not the ghetto out of the nigger, is that it?

BALLARD. Are you joking? All I want is some straight answers.

Bayliss’s response casts Pembleton’s statement about sexually voracious Black men as an oversensitive reaction to Ballard’s point, but Pembleton doesn’t relent. Referring to “ghetto niggers” intensifies the dispute, causing Ballard to suggest that Pembleton deliberately misreads her comment to infer racist implications that don’t exist. Gharty then claims that the Wilsons’ reputation won’t suffer from police scrutiny because the family has half of City Hall, Giardello, and Pembleton in their pocket:

PEMBLETON. Excuse me, I’m in someone’s pocket?

GHARTY. Hey, this is Baltimore. They’re Black, successful. That’s the deal. End of story. This is your city, Pembleton. Your house. Your department. Your rules.

PEMBLETON. Oh, so it wasn’t that way when the Italians ran it or when the Irish owned it? How many favors have been called in in the name of the Knights of Columbus or the St. Michael’s Society, huh?

Pembleton refutes Gharty’s statement about African Americans privileging themselves within the Baltimore Police Department by reminding Gharty that departmental favoritism has long depended on ethnicity. Pembleton also illustrates the subtle point that these racial and ethnic groups resemble one another more than they diverge by using bureaucratic power to benefit their own members. Pembleton, indeed, doesn’t deny that race and ethnicity are factors in investigative or administrative decisions but instead places this lamentable truth in its broader historical context.

The scene’s most explosive exchange, however, occurs when Gharty, upset by the special treatment that the Wilsons have received, tells Pembleton, “You’re the errand boy here, not me.”

PEMBLETON. I’m a boy now?

GHARTY. Oh, don’t bait me, you son of a bitch! I didn’t use the word that way! I didn’t use the word that way!

PEMBLETON. Why don’t you crawl up to one of those, uh, Hampden gin mills and buy a round for your Irish brothers on me and, and cry the blues about how your time has passed, okay?

This heated confrontation depicts how rigidly each man clings to his preconceptions. The term errand boy may not have specific racist connotations in the context in which Gharty employs it, but his enraged reaction when Pembleton bristles at having the word boy applied to him suggests that Gharty thoughtlessly employs a term that has historically infantilized, diminished, and demeaned Black men.

Pembleton, in turn, again insults Gharty’s Irish background by accusing Gharty and his white brethren of bemoaning their reduced importance in the Baltimore Police Department’s new hierarchy. Pembleton recognizes a tendency in ethnic white men to claim positions of authority, power, and influence by unfairly excluding racial minorities but then complain that those same people—after years of struggle to achieve the authority that has been unjustly denied them—illegitimately usurp political power. The sense that history has abandoned white Americans (particularly white men) thereby justifies the prejudice that white men should control America’s centers of power to prevent African Americans from wrongly excluding white people from the political, social, and economic institutions that have historically oppressed and marginalized non-white peoples.

Pembleton and Gharty’s argument deftly criticizes institutional racism, ethnic grievances, and personal animus. David Simon prevents any single character from possessing the moral high ground, resulting in a scene whose political ambivalence produces rich dramatic texture. This quarrel’s rawness illustrates how honestly Homicide faces racial division and how capably Simon integrates socially realistic themes into his television writing. The situation becomes even more complex when Pembleton, enraged by his confrontation with Ballard, Bayliss, and Gharty, questions Felix to prove that the man had no reason to murder Brierre. Wilson, however, confesses to having consensual sexual intercourse with the young woman. Pembleton’s palpable disappointment at this news forces him to realize that Ballard’s concerns were justified. Wilson expresses shame at betraying his wife’s loyalty but soon hires an attorney to protect his legal interests, leaving Pembleton to re-evaluate his faith in Wilson’s rectitude.

“Blood Ties (Part 2)” is David Simon at his best. The episode, by shattering Felix’s spotless public image, forces Pembleton and Giardello to question their own assumptions about a heroic civic figure whom they respect, yet the story doesn’t certify Gharty’s careless accusations of racial bias and protectionism. The episode instead mines the ambiguities of American race relations to display the individual, institutional, and ideological compromises that the nation’s contested racial history forces upon its citizens.