The Right Stuff

Even 35 years after its premiere, Spike Lee's Do the Right Thing remains a bracing and intelligent masterpiece.

Note to The Vestibule’s subscribers: Tough as it may be to believe, 30 June 2024 marked the 35th anniversary of the theatrical release of Spike Lee’s Do the Right Thing. As my 2014 book Spike Lee: Finding the Story and Forcing the Issue argues, Lee’s third movie is not merely a great film but also a landmark entry in the American cinematic canon, which makes its failure to be nominated for Best Picture at the 1990 Academy Awards—coupled with the fact that Bruce Bereford’s superbly acted, yet insistently cloying 1989 screen adaptation of Alfred Uhry’s 1987 stageplay Driving Miss Daisy did win—seem more unbelievable all these years later.

Kim Basinger didn’t let the Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences’s membership off the hook for this “oversight” (the kindest term I can ascribe to it) when, on 26 March 1990, the Oscar ceremony was held at Los Angeles’s Dorothy Chandler Pavilion. While introducing Peter Weir’s Dead Poets Society as one of 1989’s five Best Picture nominees (the others being Driving Miss Daisy, Oliver Stone’s Born on the Fourth of July, Phil Alden Robinson’s Field of Dreams, and Jim Sheridan’s My Left Foot), Basinger prefaced her scripted comments with impromptu remarks that speak just as powerfully today as they did 35 years ago: “We’ve got five great films here, and they’re great for one reason: because they tell the truth. But there is one film missing from this list that deserves to be on it because, ironically, it might tell the biggest truth of all. And that’s Do the Right Thing.”

Lee’s movie did receive two nominations: Danny Aiello for Best Actor in a Supporting Role (for his fabulous performance as pizzeria proprietor Salvatore “Sal” Frangione) and Spike Lee (for Best Original Screenplay), so, while Do the Right Thing wasn’t shut out of the 1990 Oscars, as some people mistakenly believe, it received far less respect than it deserved. Plus, both lost (Aiello to Denzel Washington in Edward Zwick’s Glory and Lee’s screenplay to Tom Schulman’s Dead Poets Society script), so the sense that the Academy Awards unjustifiably shortchanged Do the Right Thing has persisted for good reason no matter how many times we remind ourselves that the Oscars reward popularity and studio press campaigns more than cinematic art.

Even so, Do the Right Thing won in the long run. How many people still talk about Driving Miss Daisy except as a prime example of Hollywood’s inability to deal with controversial social issues—foremost among them race, racism, and the depredations of White supremacy—in any powerful manner, instead preferring sanitized, milquetoast, and comforting narratives of uplift, rapprochement, and cooperation meant to leave us, the filmgoing public, misty-eyed at the “progress” that America’s supposedly made despite our lived experience telling us the opposite?

Beresford’s movie sports marvelous performances by Jessica Tandy and Morgan Freeman, yet remains the principal counterpoint to DRT’s bracing, intelligent, and inventive narrative about how, on the hottest day of the summer, one Bedford-Stuyvesant block erupts into violence in response to an act of police brutality that’s still shocking to watch—and that should be shocking to watch—even 35 years later. That’s a long, rambling, and polite way of saying that Driving Miss Daisy is what legendary novelist and screenwriter William Goldman, in his 1983 book Adventures in the Screen Trade: A Personal View of Hollywood and Screenwriting, calls movies that tell comforting lies rather than difficult truths: “Hollywood horseshit.”

Do the Right Thing isn’t, so, to commemorate its 35th anniversary, I now present Finding the Story and Forcing the Issue’s second chapter, titled “The Right Stuff.” This exceptionally l-oo-nnn-gggg piece tackles Spike Lee’s third movie from many different angles that I hope, dear reader, edify—rather than bore—you. Although I’ve massaged the prose where necessary and aligned this chapter with The Vestibule’s house style, it remains much as it was when first published in 2014.

Although I could write an entirely new chapter about how distressingly relevant Do the Right Thing remains three-and-a-half decades after is release, the following anecdote (taken from the Spring 2024 “Major Authors” course that I taught in the University of Guam’s Division of English & Applied Linguistics, a class devoted to Spike Lee’s career) should suffice. Only four students enrolled in this couse, making it a terrific, intensive seminar in which we discussed Lee’s films as artistic works and as cultural products of their times.

All four students were impressed by Lee’s aesthetic, narrative, and directorial gifts, as well as his sharp mind and take-no-prisoners attitude, but, after reading Do the Right Thing’s screenplay and watching the film, one student, Sia, offered this telling comment at the beginning of our first conversation about the film: “This movie came out in 1989, but it could’ve come out yesterday. That’s amazing and troubling. What’s it say about our country that the attitudes Spike Lee captures in Do the Right Thing haven’t changed much, if at all, and that these things keep happening?”

Yes, Sia, precisely right. The fact that neither I nor anyone else can definitively answer this question in any positive way dispiritingly confesses how far we haven’t come and how far we still have to go. Spike Lee has acknowledged this sad truth many times over the years, saying in a 2019 New York Times interview celebrating Do the Right Thing’s 30th anniversary, “So a lot of things in this film, that even though it was written 31 years ago, are still happening today. Black and brown people are still being murdered today by police forces across the United States of America. And the people who inflict this death walk free. Don’t get fired, don’t get suspended.”

No single book chapter or newsletter post can reckon with how powerful, how remarkable, and how shattering a film Do the Right Thing is, but here’s hoping this extended meditation upon its cinematic sophistication helps clarify why Spike Lee’s third movie is as great and troubling a viewing experience as it is.

And if you haven’t seen it lately, please watch Do the Right Thing the next time you sit down in front of your television (or whatever screen you prefer). You’ll be amazed, upset, astounded, and saddened—but certainly not disappointed—by it’s quality.

All the best—Jason

Do the Right Thing

Directed by Spike Lee

Screenplay by Spike Lee

Starring Danny Aiello, Rick Aiello, Paul Benjamin, Ossie Davis, Ruby Dee, Richard Edson, Giancarlo Esposito, Frankie Faison, Robin Harris, Samuel L. Jackson (as Sam Jackson), Martin Lawrence, Joie Lee, Spike Lee, Bill Nunn, Steve Park, Luis Antonio Ramos, Christa Rivers, Miguel Sandoval, Roger Guenveur Smith, Leonard L. Thomas, John Turturro, Frank Vincent, Steve White, Ginny Yang, and introducing Rosie Perez

120 minutes

Released 19 May 1989 (at the Cannes Film Festival), 30 June 1989 (in limited American theatres), & 21 July 1989 (in all other American cinemas)

1. Critical Conditions

Do the Right Thing, in the 35 years since its 1989 theatrical release, has become Spike Lee’s best-known, best-remembered, and best-regarded feature film. So much mainstream and scholarly commentary about Lee’s third movie exists that confronting this extensive material exposes the reader to an onslaught of differing opinions, responses, and analyses that testify to Do the Right Thing’s now-central status, both within Lee’s filmography and within American cinema.

The American Film Institute, for instance, includes Do the Right Thing in its “100 Years . . . 100 Movies” list of the best American films produced during the 20th Century;1 the British Film Institute’s Sight and Sound Directors’ 100 Greatest Films of All Time Poll places Do the Right Thing as the 29th-best movie out of 100 international films (between Martin Scorsese’s Goodfellas and Dziga Vertov’s Man with a Movie Camera);2 the National Society of Film Critics cites Do the Right Thing as the 27th entry in its “100 Essential Films” list;3 the New York Times considers Do the Right Thing one of the “Best 1,000 Movies Ever Made”;4 and, in a 1999 decision that secures Do the Right Thing’s status as a significant American artwork, the National Film Preservation Board placed it in the United States National Film Registry.5

The movie’s numerous academic citations, to take another measure, indicate Do the Right Thing’s importance to film, media, and literary scholars. These honors form a general consensus, particularly advanced by popular-press observers, that Do the Right Thing is Lee’s earliest (and perhaps only) masterpiece.

The mixed reviews that attended the film’s opening, therefore, may surprise viewers accustomed to hearing Do the Right Thing praised not merely as Lee’s best movie, but as perhaps the greatest feature film ever made about American race relations. W.J.T. Mitchell, in his perceptive essay “The Violence of Public Art: Do the Right Thing,” comments upon the curious effect that the film’s ascent to classic status produces in Lee’s moviemaking career: “One of the interesting developments in the later reception of DRT has been its rapid canonization as Spike Lee’s ‘masterpiece.’ Critics who trashed the film in 1989 now use it as an example of his best, most authentic work in order to trash his later films (most notably Malcolm X).”6

This outcome, among many crucial observations in Mitchell’s article, indicates just how contested Do the Right Thing was upon its release. Lee’s movie, indeed, became a lightning rod for criticism not only of its filmmaker’s supposed political opportunism but also of the difficult state of race relations in New York City (and, by extension, the United States of America). Mitchell may be among Do the Right Thing’s finest academic analysts, but the initial mainstream response to Lee’s movie illuminates the racial animus that afflicted even educated (and supposedly enlightened) popular-press critics.

David Denby, for example, concludes “He’s Gotta Have It,” his 26 June 1989 New York Magazine review of Do the Right Thing, by stating, “If an artist has made his choices and settled on a coherent point of view, he shouldn’t be held responsible, I believe, if parts of his audience misunderstand him. He should be free to be ‘dangerous.’ But Lee hasn’t worked coherently. The end of this movie is a shambles, and if some audiences go wild, he’s partly responsible.”7 Privileging narrative coherence, however, is a serious misreading of Lee’s stylized, ever-changing film. The writer-director structures Do the Right Thing as a series of genial vignettes about the downtrodden residents of a single Bedford-Stuyvesant block who, on the hottest day of the summer, see their polyglot lives descend into racial conflagration.

Denby’s suggestion that certain audiences might “go wild” is, as Lee himself points out in numerous articles and interviews,8 racially coded language that presumes younger Black viewers will become violent after watching the movie’s conclusion, in which New York City Police Department officers murder a young African-American man named Radio Raheem (Bill Nunn). This callous action provokes the destruction of the movie’s principal location, Sal’s Famous Pizzeria, by the block’s furious Black and Latino residents. Denby’s incoherent perspective identifies Do the Right Thing as an unrealistic story whose messy, violent ending is nonetheless so authentic that “some audiences” (read: Black teenagers) may recapitulate its rage.

Denby’s review, despite these problems, can’t fully dismiss Do the Right Thing. Denby admires the film’s well-crafted visuals by commending Ernest Dickerson’s cinematography and applauds the story’s comic touches by declaring, “the first three quarters of the movie has the jumping vitality and buoyant, light touch of a good musical.”9 Denby finds Do the Right Thing to be significantly better than Lee’s second film, 1988’s School Daze, but still condemns Do the Right Thing’s urban naïveté: “Lee’s version of a poor neighborhood is considerably sanitized, without rampaging teenagers, muggers, or crack addicts.”10

Denby, in other words, speciously assumes that most poor New York City neighborhoods are crime-infested dystopias beset by out-of-control young people, meaning that accurate fictional representations of these places require Lee to include elements that Do the Right Thing omits. Denby, under the guise of correcting Lee’s skewed vision, perpetuates racial stereotypes about economically depressed communities of color that not only pervaded late-1980s New York City but also reveal his unthinking (or uncaring) prejudices.

New York Magazine’s political reporter, Joe Klein, goes even further in “Spiked?,” a column published in the same 26 June 1989 issue as Denby’s review, by linking David Dinkins’s mayoral prospects to Do the Right Thing, which Klein calls, “Spike Lee’s reckless new movie about a summer race riot in Brooklyn . . . which opens June 30 (in not too many theaters near you, one hopes).”11 Klein fears the reaction of African-American viewers: “If Lee does hook large black audiences, there’s a good chance the message they take from the film will increase racial tensions in the city. If they react violently—which can’t be ruled out—the candidate with the most to lose will be David Dinkins”12 (the Manhattan Borough president who successfully opposed Ed Koch and Rudy Giuliani to become, on 7 November 1989, New York City’s first African-American mayor).

This claim’s unapologetic bigotry leads Klein to note that, despite the “almost Dickensian quality to [Lee’s] sense of slum life” and the “wonderful characters who are at once simple and complicated—poignant and ridiculous, dangerous and funny,” Lee is “a classic art-school dilettante when it comes to politics” whose film reflects “the latest riffs in hip black separatism rather than taking an intellectually honest look at the problems he’s nibbling around.”13

Even more damning for Klein is that, “Like Stokeley Carmichael, [Lee] is a middle-class intellectual trying to prove his solidarity with ‘the people’ by demonstrating his outrage over white oppression.”14 Do the Right Thing, in Klein’s estimation, boils down to two messages for Black viewers: “The police are your enemy” and “White people are your enemy, even if they appear to be sympathetic.”15

Klein’s analysis features so many misunderstandings of Do the Right Thing that the critical viewer scarcely knows where to begin. Lee, however, rebukes Klein’s and Denby’s backward views of African-American audiences (in a letter published under the title “Say It Ain’t So, Joe” in New York Magazine’s 17 July 1989 issue) by noting, “Klein and Denby were so busy accusing me of inciting the black masses to riot, they didn’t stop to take stock of their own inferences.”16

Lee, moreover, defends Do the Right Thing as telling “the story of race relations in this city from the point of view of black New Yorkers” and as being “very accurate in its portrayal of the attitude that black and Hispanic New Yorkers have toward the police.”17 Invoking accuracy doesn’t deny Do the Right Thing’s insistent stylization, but Lee’s assertion of his film’s attitudinal realism forces viewers to consider just how true to life Do the Right Thing is, a topic that’s fascinated mainstream and scholarly commentators ever since.

Stanley Crouch, not to be outdone by Denby and Klein, derides Do the Right Thing’s portrait of American bigotry in his 20 June 1989 Village Voice article (provocatively titled “Do the Race Thing: Spike Lee’s Afro-Fascist Chic”) by pronouncing Lee’s film the “sort of rancid fairy tale one expects from a racist.”18 Amiri Baraka, in his essay “Spike Lee at the Movies,” dismisses Do the Right Thing as the work of “the quintessential buppie, almost the spirit of the young, upwardly mobile, Black, petit bourgeois professional” who, as part of “the middle class [that] most directly benefited from the militant sixties, as far as the ending of legal American apartheid and the increased access to middle-management resources are concerned, not only take it for granted because they have not struggled for this advance, but believe it is Black people’s fault that we have not made more progress.”19

Terrence Rafferty’s long, intriguing, and misguided New Yorker review (titled “Open and Shut”) claims that Do the Right Thing, despite its visual inventiveness, “winds up bullying the audience—shouting at us rather than speaking to us. It is, both at its best and at its worst, very much a movie of these times.”20 Murray Kempton’s “The Pizza Is Burning!,” his 28 September 1989 New York Review of Books article about Do the Right Thing, claims, “American artists from Mark Twain to Spike Lee have confronted the conflict between white and black for more than a century, and it would not be easy to recall many scenarios that so heavily and pitilessly loaded the dice against the better side” before proclaiming Mookie (Spike Lee), the pizza deliveryman who functions as one of the film’s many down-on-his-luck protagonists, to be “not just an inferior specimen of a great race but beneath the decent minimum for humankind itself.”21

Kempton’s caustic appraisal of Do the Right Thing’s central character leads W.J.T. Mitchell to call his (Kempton’s) essay “perhaps the most hysterically abusive of the hostile reviews”22 to illustrate the movie’s contested reception. Other observers found different faults with Do the Right Thing, particularly the film’s refusal to examine the structural causes of American racism and Lee’s unwillingness to develop his female characters in any real depth. Notable scholarly analyses offer similar criticisms, thereby agreeing that Do the Right Thing, no matter how good it may be, isn’t as fine or as significant a movie as its reputation suggests.

The film, indeed, provokes such divergent responses that it risks falling into a critical netherworld of political, cultural, and ideological mystification from which it can’t hope to emerge. Toni Cade Bambara, in her essay about Lee’s sophomore movie (titled “Programming with School Daze”), identifies this characteristic not only as integral to Lee’s cinematic approach but also as evidence of his talent. The diversity of viewers who “champion Spike Lee films”—sexists, homophobes, progressives, reactionaries, and independent thinkers—do so “not because the texts are so malleable that they can be maneuvered into any given ideological space, but because many extratextual elements figure into the response. . . . That the range of spectators is wide speaks to the power of the films and the brilliance of the filmmaker.”23

Such praise notwithstanding, David Denby, Stanley Crouch, and Murray Kempton (among others) remain unimpressed by Do the Right Thing, raising the possibility that the movie’s critical rehabilitation is a sham. Do the Right Thing’s admirers, however, note that Lee’s superbly crafted slice-of-life drama tackles uncomfortable truths about race and racism. Their best representative is Roger Ebert, who, in his original 30 June 1989 review (published in the Chicago Sun-Times), declares, “Lee’s writing and direction are masterful throughout the movie; he knows exactly where he is taking us, and how to get there, but he holds his cards close to his heart, and so the movie is hard to predict, hard to anticipate. After we get to the end, however, we understand how, and why, everything has happened.”24

Ebert, indeed, implicitly disputes David Denby’s judgment that Do the Right Thing’s conclusion is a poorly conceived shambles to argue that the film’s structure perfectly serves Lee’s politically charged narrative. This observation, so simple and so powerful, is important to keep in mind when thinking about the movie’s value as narrative, as sociopolitical statement, and as entertainment.

And Ebert’s esteem only grew with time. He begins his 27 May 2001 retrospective review (for Ebert’s “Great Movies” series) this way: “I have been given only a few filmgoing experiences in my life to equal the first time I saw Do the Right Thing. Most movies remain up there on the screen. Only a few penetrate your soul. In May of 1989 I walked out of the screening at the Cannes Film Festival with tears in my eyes. Spike Lee had done an almost impossible thing,” which, in Ebert’s estimation, is making “a movie about race in America that empathized with all the participants.”25

This response credits Do the Right Thing as a full-throated work of art to contradict Murray Kempton’s hyperbolic dismissal, implying that Lee’s controversial third film provokes, and even cajoles, viewers into debating its fundamental themes. The resulting popular-press disagreements have spurred cinema and media specialists to transform Do the Right Thing from a cultural cause célèbre into a touchstone of contemporary film scholarship, one whose ongoing relevance to America’s racial fissures makes it a masterwork that’s stood the test of time. This judgment, in perhaps the movie’s saddest resonance, offers its own damning commentary about its nation’s political sclerosis in the 35 years since Do the Right Thing’s release.

2. Academic Adventures

The numerous scholarly articles devoted to Lee’s third movie prompt Norman K. Denzin, in his fine essay “Spike’s Place,” to comment, “Little new can be written about DRT.”26 This conviction, however, should neither obscure Do the Right Thing’s significance nor overlook the film’s flaws. Denzin finds the movie’s representation of African-American communities and characters problematic because “Lee reduces the film’s conflict to a dispute between personalities, to personal and group bigotry, not to the larger structures of institutional racism,”27 thereby adopting a position influenced by three major, early contributions to Do the Right Thing scholarship: bell hooks’s 1989 essay “Counter-Hegemonic Art: Do the Right Thing”; Wahneema Lubiano’s 1991 article “But Compared to What?: Reading Realism, Representation, and Essentialism in School Daze, Do the Right Thing, and the Spike Lee Discourse”; and Ed Guerrero’s 1993 book Framing Blackness: The African American Image in Film.28

All three texts take Do the Right Thing to task for its simplistic approach to American racism’s political, sociological, and economic causes. Their authors challenge the movie’s august reputation by concluding that Do the Right Thing is a conservative cinematic portrait of social bigotry that focuses on individuals rather than institutions.

Hooks repeatedly makes this point in “Counter-Hegemonic Art,” stating in a particularly hard-hitting passage, “Do the Right Thing does not evoke a visceral response. That any observer seeing this film could have thought it might incite black violence seems ludicrous,” because, hooks writes, “it is highly unlikely that black people in this society who have been subjected to colonizing brainwashing designed to keep us in our place and to teach us how to submit to all manner of racist assault and injustice would see a film that merely hints at the intensity and pain of this experience and feel compelled to respond with rage.”29

Lee’s dramatic approach, in hooks’s view, founders on its inability to explore how systemic racism imperceptibly perpetuates itself, preferring instead to focus on characters who, by struggling to maintain dignity within their unfair society, cannot criticize (or even comprehend) the structural forces that restrict their lives: “The film does not challenge conventional understandings of racism; it reiterates old notions. Racism is not simply prejudice. It does not always take the form of overt discrimination. Often subtle and covert forms of racist domination determine the contemporary lot of black people.”30

This final charge identifies Lee’s greatest failing in Do the Right Thing as his refusal to question the economic order that privileges White ownership in the film’s Bedford-Stuyvesant setting, which restricts Do the Right Thing’s portrait of racial animus to parochial rather than institutional concerns. Even worse, hooks implies that Lee soft-pedals the sting (if not the agony) of racism to blame his working-class Black characters for their diminished political, economic, and social opportunities.

Lee’s Do the Right Thing production journal—written in collaboration with Lisa Jones and published in the movie’s companion volume, Do the Right Thing: A Spike Lee Joint—disputes this last criticism by stating, in its inaugural entry (dated 25 December 1987), “In this script I want to show the Black working class. Contrary to popular belief, we work. No welfare rolls here, pal, just hardworking people trying to make a decent living.”31 Lee, rather than judging, berating, or belittling the working-class African Americans and Latinos who populate his film’s fictional Bed-Stuy block, defends them by challenging the largest stigma affecting their daily lives: that they use welfare programs to avoid earning money at good, socially approved occupations.

This stereotype had gained tremendous resonance in American political discourse by Do the Right Thing’s 1989 release thanks to the racial rhetoric of President Ronald Reagan’s repeated invocations of welfare queens, along with his many other coded references to poor, mostly African-American people. This discourse cemented in the minds of the wider American electorate the spurious idea that “inner-city people” (itself a code for Black and Brown Americans) are all lazy, good-for-nothing freeloaders who, to support their families, prefer taking government handouts to holding regular jobs.

This notion became so fixed in American politics that its specious factual basis had little effect on its currency, even though Chicago resident Linda Taylor, the “Cadillac-driving welfare queen” that Reagan first mentioned in his failed 1976 presidential campaign (and continued to cite throughout his successful 1980 White House bid), was a contested case of welfare fraud that Reagan and his handlers frequently mentioned during Reagan’s race-baiting campaign.32 Similar ideas promulgated during Reagan’s presidency became pervasive facts of American civic life even when demonstrably false.

Herman Gray, in the second chapter of his superlative book Watching Race: Television and the Struggle for Blackness, evaluates the rhetorical bigotry that underlies these politically influential concepts: “Although unmarked, Reagan’s references to this Chicago ‘welfare queen’ and to ‘you’ play against historic and racialized discourses about welfare at the same time they join law-abiding taxpayers to an unmarked but normative and idealized racial and class subject—hardworking whites.”33 Gray’s analysis notes how “the new right effectively appealed to popular notions of whiteness in opposition to blackness, which was conflated with and came to stand for ‘other.’ . . . As a sign of this otherness, blackness was constructed along a continuum ranging from menace on one end to immorality on the other, with irresponsibility located somewhere in the middle.”34

These notions grew into stigmas, then stereotypes, and, finally, into cultural commonplaces. Gray’s study identifies the origin of many biases against African-American working-class people prevalent in 1980s American culture, biases that Do the Right Thing takes as its subject, that Lee’s production journal questions, and that bell hooks wishes Lee’s third film would resolutely contest.

Lee’s desire to break from regressive portrayals of poor and working-class Black people remains evident throughout his journal, nowhere more clearly than in its 14 February 1988 entry: “If I’m dealing with the Black lower class, I have to acknowledge that the number one thing on folks’ minds is getting paid. It’s on everyone’s mind, lower class or not, but the issue has more consequences when you’re poor, flat broke, busted.”35 Lee, at least while conceptualizing Do the Right Thing, remembers the challenges facing his film’s disadvantaged characters, thereby rejecting the most piercing elements of hooks’s criticism. Lee’s sympathy, nonetheless, revolves around the primacy of individuals earning money rather than the structural unfairness of American capitalism.

Wahneema Lubiano, on this score, feels that Do the Right Thing’s relentless focus on money inhibits the institutional appraisal necessary to any honest examination (fictional or otherwise) of American racism. Lubiano, in “But Compared to What?,” writes that Lee “produces representations that suggest particular Euro-American hegemonic politics. His Do the Right Thing is imbued with the Protestant work ethic: There is more language about work, responsibility, and ownership in it than in any five Euro-American Hollywood productions.”36

This hegemony, for Lubiano, simplifies inherently complicated economic realities: “The film insists that, if African Americans just work like the Koreans, like the Italians, like the Euro-American brownstone owner [the character Clifton, played by John Savage], these problems could be averted; or, if you own the property, then you can put on the walls whatever icons you want; or, if you consume at (materially support) a locale, then you can have whatever icons you want on the walls.”37

Lubiano, therefore, finds Do the Right Thing’s dramatic premise unpersuasive. The film’s conflict begins when Buggin’ Out (Giancarlo Esposito), a self-styled neighborhood revolutionary (and budding Black nationalist), asks Salvatore “Sal” Fragione (Danny Aiello), owner and proprietor of Sal’s Famous Pizzeria, why he (Sal) doesn’t include photos of Black celebrities on the pizzeria’s Wall of Fame, which includes framed shots of Italian-American stars such as Joe DiMaggio, Rocky Marciano, Frank Sinatra, Robert De Niro, Al Pacino, and Liza Minnelli. Sal’s response is a paen to the rights of private-property owners: “You want brothers on the wall? Get your own place. You can do what you wanna do. You can put your brothers and uncles and nieces and nephews, your stepfather, stepmother, whoever you want. See? But this is my pizzeria. American-Italians on the wall only.”38

Lubiano finds the movie so imbued with talk of work, property, and money that it defines manhood purely in economic terms: “And its masculinist focus could be distilled into the slogan that screams at us throughout the film: ‘Real men work and support their families.’” Yet, for Lubiano, this rhetoric’s slanted view of work, men, and working men is hollow: “These representations compared to what? Within the representations of Do the Right Thing, what are the ideologies being engaged here, or critiqued here, or, more to the point, not critiqued here?”39 Lubiano comments that such narrow definitions (of manhood, of property, and of work) refuse to examine, much less indict, the Protestant work ethic that both Sal and Mookie embody.

Even Buggin’ Out barely questions the assumptions that undergird the neighborhood’s shaky economy, responding to Sal’s declaration by conceding the man’s ownership rights: “Yeah, that might be fine, Sal, but you own this. Rarely do I see any American-Italians eating in here. All I see is Black folks. So since we spend much money here, we do have some say.”

Buggin’ Out begins the economic analysis that Lubiano recommends, even going so far as to stage an attempted boycott of the pizzeria after Sal, who, rather than addressing Buggin’ Out’s point about the responsibility that he (Sal) owes his customers, responds by asking, “You looking for trouble? Are you a troublemaker? Is that what you are?” Sal brandishes a baseball bat when Buggin’ Out demands that Sal put photos of Malcolm X, Nelson Mandela, and Michael Jordan on the Wall of Fame.

No matter how correct Buggin’ Out’s point may be or how provocative Sal’s response is, the younger man fails to note the institutional barriers that prevent his fellow African Americans from receiving the same access to capital that Sal enjoys. Buggin’ Out, therefore, remains a feeble revolutionary who, much like Dap Dunlap in School Daze, seems unwilling to expend the effort necessary to building and maintaining a successful protest movement.

Lubiano finds such discussions misguided and, finally, tedious: “Against, I suppose, the long-held racist charge that African Americans neither work nor want to work, this film spends much of its running time assuring its audience that African Americans in Bed-Stuy certainly do value work! (By its end, I am so overwhelmed by its omnipresent wage-labor ethos that I find myself exhausted).”40

Lubiano rightly perceives Lee’s desire to alter the stereotypical images of shiftless Black people that characterized Reagan-era America, but she finds that, by doing so, Do the Right Thing reinforces the same unfair economic policies and conditions that help create those images in the first place: “I am not anti-labor; however, this film makes no critique of the conditions under which labor is drawn from some members of the community, nor are kinds of labor/work differentiated. Instead, without any specific contextualization, work is presented as its own absolute good.”41

This problem becomes worse when Lubiano considers the failed promise of the “Corner Men,” three black friends named Sweet Dick Willie (Robin Harris), Coconut Sid (Frankie Faison), and M.L. (Paul Benjamin) who sit on a street corner across from the block’s Korean-owned fruit market while drinking beer and discussing the day’s events. “Early on,” Lubiano writes, “the film promises a class critique of sorts in the discussion of Sweet Dick Willie and his buddies on the corner. M.L. begins a complaint that the Koreans, like so many other immigrant groups, move into the neighborhood and seem immediately to ‘make it,’ only to lose the focus of his critique”42 because he doesn’t (or can’t) criticize the systemic roadblocks that retard African-American progress: “The men make no mention of differential capital bases or accesses to bank loans—and there is no reason to think that vernacular language could not handle that analysis.”43

Lubiano, in this passage, interrogates Do the Right Thing’s (and Lee’s) failure to mention America’s long history of racial exclusion, particularly the unfair lending, housing, and employment practices that restricted African-American economic advancement during the 19th and 20th centuries. Do the Right Thing’s man-on-the-street perspective, to Lubiano, repudiates institutional analyses in favor of individual portraits that prevent the film from achieving the political ends that its director, in both his production journal and public appearances, hopes to dramatize.

Lubiano, in simpler language, may admire Do the Right Thing’s style, energy, and wit, yet considers it a politically contradictory narrative that can’t accomplish the ends that Lee desires: “For a filmmaker who claims the mantle of transgression, cultural opposition, political righteousness, and truth-telling, the political ambitions of this film are diffuse and, by its end, defuse into nothingness.”44

3. Scholarly Sojourns

Spike Lee’s production journal, as if to reply to Lubiano’s observations, demonstrates his willingness to upset typical depictions of American racism, although it never suggests the institutional appraisal that she recommends. Lee’s 1 January 1988 entry connects his early wish to cast Robert De Niro as Sal with Do the Right Thing’s treatment of American racism. Lee reveals that he met De Niro one year prior, “the night after the Howard Beach incident. We discussed racism and how the animosity between Blacks and Italians has escalated. I think we can make an important film about the subject.”45

The Howard Beach incident refers to the tragic event that first inspired Lee to create Do the Right Thing: just before midnight on 19 December 1986, the automobile of four African-American men driving through the predominantly Italian-American neighborhood of Howard Beach, Queens stalled on Cross Bay Boulevard. Three passengers—Michael Griffith, 23; Cedric Sandiford, 36; and Timothy Grimes, 20—tried to locate a pay phone on foot. When confronted by a group of White pedestrians yelling racial epithets, these men entered the New Park Pizzeria.

Lee’s autobiography, That’s My Story and I’m Sticking to It, collates many different accounts to describe what happened next, saying that all three men entered the pizzeria, but, when told they couldn’t use the phone to call for assistance, decided to eat. Two police officers arrived not long after, having been notified that “three suspicious black males” were inside the establishment, but departed when they determined that Griffith, Sandiford, and Grimes had done nothing wrong, which escalated the trouble when White patrons “chased the black youths out of the pizzeria toward a gang of accomplices waiting with baseball bats.”46

Grimes, pulling a knife, escaped this mob, but Sandiford was beaten unconscious. The severely injured Griffith, trying “to stagger away from his pursuers,” instead “wandered onto the busy Belt Parkway, where he was hit and killed by a passing automobile. New York erupted, witnessing the largest black protest rallies since the civil-rights movement.”47

Lee, as this description makes clear, includes so many references to Howard Beach in Do the Right Thing that audiences at the time of the film’s 1989 release, particularly in New York City, couldn’t miss them: The main action occurs in an Italian-American pizzeria, Sal wields his Louisville Slugger baseball bat to assert dominance, and his son Pino (John Turturro) utters racial epithets at nearly every turn.

Lee, however, reverses Howard Beach’s primary setting to comment upon the changing urban demographics that the United States had witnessed during the previous thirty years. Rather than tell the story of African Americans stranded in a mostly Caucasian neighborhood, Lee isolates his three Italian characters—Sal, Pino, and Sal’s younger son, Vito (Richard Edson)—in Black and Latino Bedford-Stuyvesant.

Sal, in other words, hasn’t fully participated in the “White flight” of the 1950s, 1960s, and 1970s that saw Caucasian residents and business owners abandon American cities for more suburban areas as African Americans, Latinos, and Asians moved into previously all-White enclaves. Sal proudly plies his trade in Bed-Stuy, although he and his family now live in Bensonhurst, driving to work each morning to spend their days amongst the Bed-Stuy block’s minority residents.

Do the Right Thing, therefore, offers an African-American perspective, aesthetic, and approach to its narrative that strikes many viewers as authentic. Lee, indeed, strives for authenticity, as his 1 January 1988 production-journal entry states: “Truth is more important than an evenhanded treatment of the subject. No matter what, the story has to be told from a Black perspective.”48 Even so, Do the Right Thing avoids addressing the systemic racism noted in bell hooks’s and Wahneema Lubiano’s essays, preferring a granular approach that depicts the lives of individual human beings trying to survive the racial, social, and economic circumstances they’ve inherited.

Critical viewers, however, should recognize that neither Do the Right Thing nor its writer-director claims to deliver a neutral account of urban racism. The movie, despite all talk of its realism, naturalism, and authenticity, is a highly stylized representation of American race relations, as well as an effective response to the Howard Beach incident (among other tragic confrontations between Black New Yorkers and the New York Police Department in the years immediately preceding the movie’s release49), not a cinematic documentary offering objective viewpoints.

Although hooks and Lubiano criticize Do the Right Thing’s inability to diagnose racism’s institutional foundations, Lee’s production journal demonstrates his awareness of the socioeconomic issues in play. The 4 January 1988 entry, in fact, equates social class with educational achievement: “Both Pino and Vito only made it through high school. They will work in their father’s pizzeria probably for the rest of their lives and are ill-equipped to do otherwise. They’re lower-middle class and basically uneducated.”50

Pino’s toxic racism, as the character’s dialogue and John Turturro’s superb performance confirm, has many causes, but Pino expresses disdain for customers he calls “niggers” (even telling Sal, “I don’t like being around them. They’re animals”) due to the rage that he feels knowing his life is no better than theirs. Pino’s economic opportunities, to state the matter bluntly, are scarcely broader than the African-American residents he serves every day, yet detests. Even Pino’s claims that he works harder than everyone on the block (except Sal) ring hollow because Pino has no appreciable skills beyond taking orders, making change, cleaning the shop, and occasionally helping his father cook pizza (although Sal lords over this task as much as he does all others).

Do the Right Thing, indeed, compares Pino to the person he most loathes, Mookie, by paralleling their circumscribed choices. This thematic twinning increases the tension between both men as the film unfolds, for Do the Right Thing exposes Pino’s hatred of Mookie as a pernicious form of self-hatred. Lee’s January 4th journal entry makes this point, as well: “Pino, Vito, and Mookie have many similarities. All three are high school graduates and are stuck in dead-end jobs. They are trapped. They would never discuss it amongst themselves.”51

Pino and Mookie, therefore, have no class consciousness (and indeed never directly discuss socioeconomic issues), but the scene just before the altercation among Sal, Buggin’ Out, and Radio Raheem that precipitates the pizzeria’s destruction captures the subtext of Lee’s January 4th entry. Sal, happy that the shop has done good business during the day, praises Pino, Vito, and Mookie as a family that works together to achieve the common goal of enhancing their economic interests. He says that the shop should be renamed Sal and Sons Famous Pizzeria, even telling Mookie, “there’s always gonna be a place for you here, right here at Sal’s—Sal’s Famous Pizzeria—because you’ve always been like a son to me.”

The shocked, disbelieving, and silent expressions on Pino’s, Vito’s, and Mookie’s faces are testaments to Turturro’s, Edson’s, and Lee’s acting talents, for they perfectly capture the stage directions specified by Do the Right Thing’s screenplay: “The horror is on their faces, with the prospect of working, slaving in Sal’s and Sons Famous Pizzeria, trapped for the rest of their lives. Is this their future? It’s a frightening thought.”52 Lee’s reference to “slaving” is deliberate, drawing out the scene’s most troubling implication as written, performed, and edited: Pino, Vito, and Mookie are condemned to a life of wage slavery as long as they work for Sal, who, despite his effusive demeanor, is little more than a benevolent tyrant who controls their future earnings and, consequently, the quality of their future lives.

Lee even revisits this notion in his 2012 movie Red Hook Summer by showing “Mr. Mookie” (as this film’s end credits identify him) still delivering pies for Sal’s Famous Pizzeria in Brooklyn’s Red Hook district. Mookie never mentions Pino or Vito by name in Red Hook Summer, but the fact that he remains a pizza deliveryman 23 years after Do the Right Thing’s events implies that they, too, still work at Sal’s.

Do the Right Thing, therefore, is as symbolic as realistic by presenting the economic hierarchy of Sal’s Famous Pizzeria as a microcosm of late-1980s American capitalism. Sal doesn’t see himself as an oppressor, but rather as a man who offers opportunity to everyone: his family, his customers, and his sole African-American employee. This hidden, subtextual discourse counters some of hooks’s and Lubiano’s criticisms about the movie’s inadequacies, yet fails to convince Ed Guerrero that Do the Right Thing is a groundbreaking work of American cinema even if it “explores the great unspeakable, repressed topic of American cultural life: race and racism.”53 Guerrero states that Lee’s mastery of the techniques of Hollywood studio filmmaking leads him into “a contained, mainstream sensibility” that finds the director “diligently struggling to learn the conventions and clichés of market cinema language, instead of struggling to change the dominant system by creating a visionary language of his own.”54

Guerrero, indeed, considers “the glossy, wide-screen, poster-bright colors, sanitized streets, overworked theatrical settings, and up-to-the-moment fashions that constitute so much” of Do the Right Thing’s visual style deficient because, “in contrasting irony, it is the film’s alleged sense of ‘authenticity’ and ‘realness’ that some critics have praised. But the film’s slick, color-saturated look has the effect of idealizing or making nostalgic the present, rather than dramatizing any deep sense of social or political urgency.”55

Do the Right Thing’s signature look—the bold primary colors in which Lee and cinematographer Ernest Dickerson bathe nearly every scene, combined with canted camera angles that make everyday conversations and confrontations unsettling—becomes, in Guerrero’s analysis, evidence of political naïveté, particularly the narrative’s apparent dismissal of collective political action. The movie, Guerrero writes, makes its two “proto-revolutionaries,” Buggin’ Out and Radio Raheem, “supercilious and unreasonable characters advocating the most effective social action instrument of the civil rights movement, the economic boycott,” but, in the end, Do the Right Thing’s audience sees “the possibility of social action dismissed by the neighborhood youth for the temporary pleasures of a good slice of pizza,” meaning that “the film trivializes any understanding of contemporary black political struggle, as well as the recent history of social movements in this country.”56

Guerrero, like hooks and Lubiano before him, charges Lee with adopting an individualist stance that ignores, when not actively repudiating, organized political protest as an effective response to institutional racism: “Thus, Lee inadvertently gives way to dominant cinema’s reflex strategy of containment, that of depicting complex social conflicts as disputes between individuals, where deliberated collective action is either impossible or unnecessary.”57 Lee’s heart, in other words, may be in the right place, just as his intentions may be for the best, but Do the Right Thing is neither a guerrilla film nor a call to arms. For Guerrero, the movie fails to address the true origins and outcomes of American racism.

The important objections raised by hooks, Lubiano, and Guerrero dispute Do the Right Thing’s classic status and extend criticisms registered in the unappreciative reviews that greeted the film’s 1989 release, but without the bigotry evident in Joe Klein’s and David Denby’s articles. Indeed, the nuanced arguments that hooks, Lubiano, and Guerrero construct pose sophisticated challenges for later assessments of Do the Right Thing’s quality, effectiveness, and value.

One conclusion seems clear: Do the Right Thing cannot fulfill the diverse expectations of its many viewers, critics, and scholars (as, indeed, no film can). This truth, however, shouldn’t suggest that Do the Right Thing remains so ambiguous that it means whatever particular audiences wish it to mean. The movie, as Toni Cade Bambara suggests, isn’t so malleable that it fits into innumerable ideological boxes, even if Do the Right Thing permits multivalent reactions. Despite the prognostications of Joe Klein, David Denby, and Norman Denzin, Lee’s film reveals different facets with each viewing that force us to consider and reconsider its events, effects, and themes.

4. Saturday Night (& Day) Fever

The scholarly articles that defend Do the Right Thing, in whole or in part, are as numerous as those sources that condemn it. Important texts in this regard include Nelson George’s “Do the Right Thing: Film and Fury” (first published in Five for Five: The Films of Spike Lee, the retrospective 1991 volume that celebrated the release of Lee’s fifth movie, Jungle Fever), Mark A. Reid’s edited 1997 essay anthology Spike Lee’s “Do the Right Thing” (particularly Douglas Kellner’s “Aesthetics, Ethics, and Politics in the Films of Spike Lee” and W.J.T. Mitchell’s aforementioned “The Violence of Public Art: Do the Right Thing”), S. Craig Watkins’s 1998 book Representing: Hip Hop Culture and the Production of Black Cinema, Paula J. Massood’s 2003 book Black City Cinema: African American Urban Experiences in Film, and, especially, Dan Flory’s 2006 article “Spike Lee and the Sympathetic Racist.”

Each writer considers Lee’s third movie to be a complicated cinematic probing of American race and social class. Massood, indeed, argues that Do the Right Thing succeeds precisely where bell hooks, Wahneema Lubiano, and Ed Guerrero think it fails: “Rather than exploring the macrocosm of causes and effects leading to the conditions on this particular block, Lee lets the block, its residents, and the day’s events reveal the conditions and pressures of the inner city.”58 Noting that the movie uses “many of the techniques introduced by the Italian Neorealists, the French New Wave, and Soviet filmmaking from the 1920s,” Massood cites literary theorist Mikhail Bakhtin’s concept of heteroglossia before arguing that Do the Right Thing “bears the influence of the French New Wave, especially in the use of the Brechtian concepts of alienation and distanciation and their related formal and narrative techniques.”59

The film, therefore, cinematically addresses “racism, its many causes and effects, and how it all plays out in this small urbanscape. Its single-block setting embodies multiple signifiers of the extradiegetic conditions affecting the neighborhood.”60 Massood, unlike hooks, finds Do the Right Thing’s granular approach (emphasizing individual over institutional concerns) to resemble Bakhtinian and Brechtian modernism by underscoring the ceaseless play of signifiers (music, costumes, colors, angles, and editing) that influence, without fully determining, the lives of the movie’s characters and the progression of its themes.

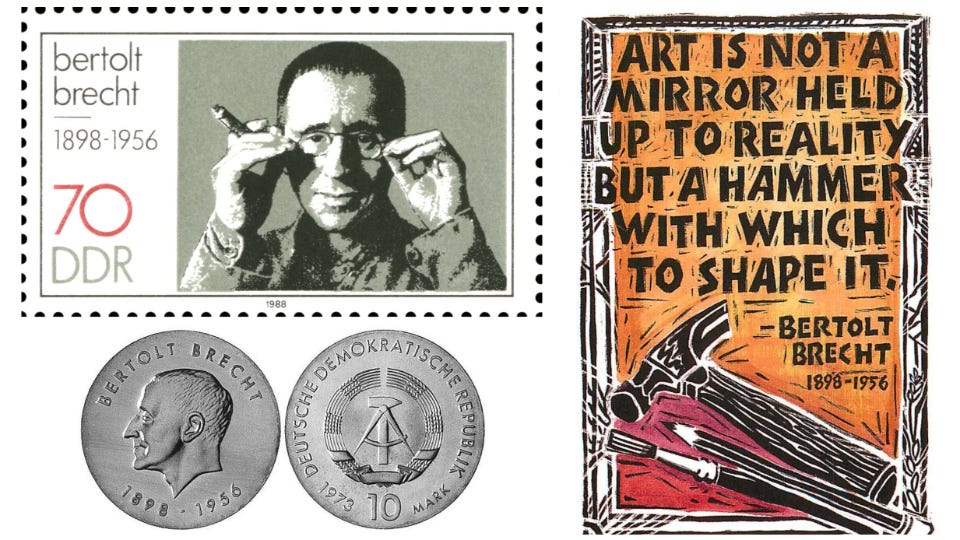

Douglas Kellner also discusses Berthold Brecht’s German modernist theater as an important and valuable forerunner of Lee’s American cinema. “Both Brecht and Lee,” Kellner writes, “produce a sort of ‘epic drama’ that paints a wide tableau of typical social characters, shows examples of social and asocial behavior, and delivers didactic messages to the audience. Both Brecht and Lee utilize music, comedy, drama, vignettes of typical behavior, and figures who present the messages the author wishes to convey.”61

This final point rehabilitates a common criticism of Do the Right Thing and Lee’s other films: that their characters function as little more than mouthpieces for their director’s social, cultural, and political beliefs, along with his pet peeves and hobby-horses. In Brecht’s plays and Lee’s films, such characters (who are perhaps better described as animated, ambulatory characteristics rather than psychologically realistic people) allow both playwright and filmmaker, in Kellner’s words, to “present didactic learning plays, which strive to teach people to discover and then do ‘the right thing,’ while criticizing improper and antisocial behavior. Brecht’s plays (as well as his prose, his film Kuhle Wampe, and his radio plays) depict character types in situations that force one to observe the consequences of typical behavior,”62 a modernist trait that Brecht’s writing shares with Do the Right Thing.

Kellner also argues that Lee’s third movie “is arguably modernist in that it leaves unanswered the question of the politically ‘right thing’ to do. By ‘modernist,’ I refer, first, to aesthetic strategies of producing texts that are open and polyvocal, that disseminate a wealth of meanings rather than a central univocal meaning or message, and that require an active reader to produce the meanings.”63 Do the Right Thing fulfills all these criteria, generating so many divergent responses that, from Kellner’s perspective, scholars like hooks, Lubiano, and Guerrero mistake the film for a realistic account of the block’s warmest day when it instead resembles a symbolist play.

Even so, Kellner points out how the movie celebrates mass-market consumerism to confirm one fundamental conclusion propounded by Do the Right Thing’s critics: “Lee excels in presenting small-group dynamics but has not been successful in articulating the larger structures—and structural context of black oppression—that affect communities, social groups, and individual lives. Thus, he does not really articulate the dynamics of class and racial oppression in U.S. society.”64 Kellner regards Lee’s personal rather than systemic focus as evidence of Do the Right Thing’s modernist, Brechtian aesthetic more than a regrettable failure, although, for Kellner, “Lee’s politics, by contrast [with Brecht’s avowed Marxism], appear more vague and indeterminate”65 in their expression, thereby promoting an ambivalence that some viewers (particularly Amiri Baraka) read as bourgeois conservatism.

Lee’s film, despite its powerful effect on viewers, isn’t the epic drama that Kellner claims, or at least not epic in the sense of covering vast historical and geographical territory. Following its characters throughout a single, 24-hour period restricts Do the Right Thing’s narrative to the more modest scope of slice-of-life fiction, causing Kellner to criticize the effect of Lee’s “tendency to use Brechtian ‘typical’ characters to depict ‘typical’ scenes. The ‘typical,’ however, is a breath away from the stereotypical, archetypal, conventional, representative, average, and so on, and lends itself to caricature and distortion.”66

Do the Right Thing, indeed, fulfills this dictum through characters who receive designations rather than names, the most prominent being Buggin’ Out; Radio Raheem; Da Mayor (Ossie Davis), a shambling alcoholic who functions as the neighborhood’s de facto mediator; and Mother Sister (Ruby Dee), a griot who watches the block’s events from her dilapidated brownstone’s front window while dispensing advice to Mookie and his sister, Jade (Joie Lee). Their stereotypical traces—or their stock roles (frustrated revolutionary, fearsome block-boy, town drunk, and old maid)—may work against Do the Right Thing’s putative realism, but these characters push critical viewers to recognize, along with S. Craig Watkins, that Lee’s movie “operated more at the level of allegory and symbolism”67 than quotidian fidelity.

For Watkins, this development liberates the movie’s story from the shackles of strict realism while paradoxically invoking real-world issues:

Thus, if we view Sal and the black youths in the film as vehicles for expressing some of the shifting racial moods and sensibilities of the late twentieth century, then the politics of the film become much more dynamic and discernible: the intensification of racial tension between black youth, downwardly mobile whites, and institutions of social control.68

Do the Right Thing, in this reading, doesn’t ignore social or institutional concerns, but instead mixes closely observed, traditionally realistic characters (Sal, Mookie, Pino) with broader types (Buggin’ Out, Da Mayor, Mother Sister) to question the economic influences and impacts, but not the origins, of American racism.

Watkins, like Paula J. Massood, notes that Do the Right Thing’s multivalent storyline—replete with unresolved themes, characters, and plots—reproduces heteroglossia, as well as the Bakhtinian concept of polyphony, to challenge classical Hollywood style’s preference for tidy and reassuring resolutions. Lee, in this film (and several others), “privileges multiple story-plots over the single-story-plot formula” in a structure that “fractures the primary story-plot. Consequently, his film narratives tend to develop acute fissures. So instead of constructing a single homogenous world, Lee opts for creating a filmic world in which a polyphony of issues, conflicts, and enigmas seem to proliferate unabashedly.”69

Do the Right Thing, in other words, leaves its audience to ponder difficult events that the film makes no effort to reconcile. Its ambivalent conclusion sees Radio Raheem dead, Sal’s Famous Pizzeria destroyed, and Mookie determined to receive his wages despite throwing a trash can through Sal’s front window. This ending subverts classical Hollywood’s preference for, in Watkins’s words, “easy resolution and narrative closure,”70 or “the happy-ending cliché” that “reaffirms dominant ideological values like individualism and patriarchy and further suggests that heroic, often male, deeds are the solution to social problems.”71 Do the Right Thing, by partially rejecting these values and deeds, criticizes racism’s social, economic, and institutional foundations to become, if not the counter-hegemonic cinema that bell hooks favors, at least a film that interrogates its era’s dominant racial ideologies.

Yet no matter how intelligently the movie’s mainstream and scholarly observers present their arguments, they rarely acknowledge the second, crucial aspect of Do the Right Thing’s setting. Every newspaper review, magazine article, and scholarly essay discusses the movie’s primary locale, sometimes criticizing this neighborhood block as too clean and too drug-free to be an authentic representation of Bedford-Stuyvesant, but rarely mentions that Do the Right Thing takes place on Saturday. This significant detail is easy to miss, but, in one of the film’s earliest scenes, Mookie’s sister Jade lies sleeping in bed when he playfully touches her lips and face, then tells her, recalling Dap Dunlap’s final plea in School Daze, to “Wake up!”

Jade, complaining about Mookie’s interference, says, “Saturday’s the only day I get to sleep late” in dialogue that also rebukes the energetic words of Mister Señor Love Daddy (Samuel L. Jackson, credited as Sam Jackson), disc jockey for neighborhood radio station WE LOVE 108FM, who, in Do the Right Thing’s opening scene, tells his listeners, “Waaaaake up! Wake up! Wake up! Wake up! Up ya wake! Up ya wake! Up ya wake! Up ya wake!” Lee’s decision to cast Jackson as Love Daddy connects Do the Right Thing even more closely to School Daze, suggesting that Do the Right Thing not only picks up where its predecessor ends but also promises to fulfill Dap Dunlap’s fervent dream of African-American characters who finally comprehend the political conditions that restrict their daily lives.

Jade’s comment, as such, ironically suggests that she prefers pursuing individual interests to the communal action that School Daze states is necessary for Black Americans to collectively advance. Jade’s perspective gains credence when she refuses to join Buggin’ Out’s boycott of Sal’s Famous Pizzeria, asking him, “What good is that gonna do, huh? You know, if you really tried hard, Buggin’ Out, you could direct your energies in a more useful way, you know?” This response illustrates the point made by hooks, Lubiano, and Guerrero that Do the Right Thing underplays (or dismisses) the benefits of organized protest to the detriment of its Black characters.

Jade, indeed, relentlessly preaches what Lubiano calls the movie’s exhausting wage-labor ethos, voicing this work ethic even more frequently than Sal and Pino. Jade badgers Mookie throughout Do the Right Thing to fulfill his responsibilities at work and home, equating his ability to earn enough money to support his young son, Hector (Travell Lee Tolson), and Hector’s mother, Tina (Rosie Perez), with Mookie’s full identity. That Mookie works on Saturday, the traditional American weekend, escapes her notice as much as Do the Right Thing’s critics.

The block’s residents fill the streets to seek relief from the day’s oppressive heat because, contrary to careless assumptions that they are idle welfare recipients, they wish to enjoy time away from their jobs. The rage that they unleash against Sal’s Famous Pizzeria after Radio Raheem’s murder, in this context, transcends its immediate cause to represent communal anger at the economic inequalities that allow Sal to prosper while everyone else struggles in economically uncertain conditions.

This reading also explains why Mother Sister (who, along with Da Mayor, represents the older generation of Black Americans who endured Jim Crow segregation) screams, “Burn it down! Burn it down!” after the police haul Raheem’s corpse away from the pizzeria. The stage directions in Lee’s screenplay offer a fascinating gloss on her anger: “One might have thought that the elders—who through the years have been broken down, whipped, their spirits crushed, beaten into submission—would be docile, strictly onlookers. That’s not true except for Da Mayor. The rest of the elders are right up in it with the young people.”72 The block’s hottest day unveils the long-simmering dismay that working-class African Americans feel when confronting the truth that they’re unimportant to the institutions that regulate their lives. The police and Sal seem to prize property over life throughout the movie, leaving the distraught onlookers to express their helplessness at Raheem’s murder by attacking the pizzeria as the only symbol of social oppression available to them.

Do the Right Thing, moreover, subtly controls its mise-en-scène to demonstrate that the block’s inhabitants aren’t universally poor: Jade wears colorful clothing and hats when visiting Sal’s; Love Daddy wears similarly distinct clothing while working his day-long shift at the radio station; Mother Sister implies that her ex-husband’s poor business sense caused her to accept tenants in her brownstone; Buggin’ Out observes that his fellow Black patrons spend “much money” on Sal’s pizza and wears new Nike shoes (thereby falling prey to the crass commercialism that Douglas Kellner criticizes); and Mookie’s introduction finds him counting money (not food stamps or welfare checks) in his bedroom.

These characters therefore exemplify Lee’s production-journal reference to hardworking people earning their keep, making Saturday, for most residents, a respite from their occupational challenges and tensions, meaning that Do the Right Thing isn’t the simple celebration of bourgeois conventionality that Amiri Baraka claims.

The movie’s Saturday setting, moreover, helps sketch its character’s polyvalent lives, while acknowledging the existence of people who buck the film’s insistence on the necessity and dignity of labor: Mother Sister tells Mookie not to work too hard in the day’s intense heat, Da Mayor sweeps the sidewalk in front of Sal’s pizzeria just long enough to accumulate the spare change that supports his alcoholism, Radio Raheem walks the block listening to Public Enemy’s anthem “Fight the Power” rather than pursuing the difficult political action that would fulfill the song’s title, and the Corner Men pontificate about the block’s problems rather than trying to solve them.

Lee’s screenplay, indeed, describes the Corner Men as having “no steady employment, nothing they can speak of; they do, however, have the gift of gab. These men can talk, talk, and mo’ talk, and when a bottle is going round and they’re feeling ‘nice,’ they get philosophical. These men become the great thinkers of the world, with solutions to all its ills.”73 Their job in Do the Right Thing’s narrative is to observe, to comment, and to advise (much like a traditional Greek chorus), not to seek financial reward.

Da Mayor likewise watches, engages, and advises his neighbors (telling Mookie, in the movie’s titular line, “Doctor, always do the right thing”), but pursues no career ambitions beyond scrounging enough money for his next drink. Mother Sister demonstrates no interest in leaving her home, remaining content to offer wisdom to whomever will listen. Saturday, for these characters, is just another day rather than a reprieve from the working world’s pressures, yet Do the Right Thing doesn’t exclude or overlook their voices even if the Corner Men, Da Mayor, and Mother Sister reject socially approved forms of industrial labor.

Lee’s third film, considered in this light, develops a discourse about the value of capitalism that may not directly challenge the wage-labor ethos that Lubiano finds pervasive, but that nonetheless undermines easy faith in earning profit to support one’s family. Mookie, after all, resists Sal’s, Pino’s, and Jade’s imprecations to be a diligent worker by taking longer to deliver pizzas than he should, even visiting Tina in an erotic sequence that finds Mookie rubbing ice cubes along her lips, thighs, and breasts. Pino and Vito argue about finishing the tasks assigned by their father, who, early in the film, presciently says, “I’m gonna kill somebody today.”

Sal, for his part, ignores his employees and his customers when Jade enters the pizzeria to make her a special meal. Money, therefore, isn’t the sole motivator for the movie’s characters even if it underscores their major actions. Do the Right Thing, indeed, cannot examine the long-term influences of institutional capitalism on American racism in the same manner as, say, David Simon’s superb, 60-episode HBO television series The Wire, but neither does the movie avoid making such points.

Lee eschews polemics in favor of vignettes that illustrate the block’s economically restrictive conditions from a ground-floor perspective. Do the Right Thing’s Saturday setting, consequently, is central to its portrayal of working- and lower-class people who cannot (or will not) defy the economic and racial restrictions they face until Radio Raheem’s murder provides the impetus to act. Their destruction of Sal’s pizzeria, in this light, isn’t as thoughtless an undertaking as critics like David Denby suggest, but instead builds upon key sequences that foreshadow the oncoming violence.

5. Sons, Slurs, & Sal

Three sequences illustrate Do the Right Thing’s complex rendering of race, class, and bigotry in late-1980s America. The first occurs when Pino, upset that Mookie uses the pizzeria’s phone for personal calls, asks, “How come niggers are so stupid?” Mookie replies, “If you see a nigger, kick his ass” before asking Pino about the man’s favorite celebrities. Pino admires Magic Johnson, Eddie Murphy, and Prince, but sees no conflict with his racist viewpoints. “Magic, Eddie, and Prince are not niggers,” Pino says. “I mean they’re Black, but they’re not really Black. They’re more than Black. It’s different.” This short dialogue displays Lee’s genius for compression, encapsulating in a few words the contradictions of American racist thought, or, as Nelson George observes in “Do the Right Thing: Film and Fury,” “one of the ironies of the post civil-rights era is that the wide acceptance of black stardom hasn’t really changed ground-level racism—something King had hoped for, but Malcolm X had anticipated.”74

Pino speaks for White ethnic men who regard themselves as hardworking, fair-minded Americans happy to credit individual Black men as outstanding contributors to society. Yet Pino and his friends demonstrate little understanding of the historical, political, and economic barriers that restrict many African Americans from achieving the success that Johnson, Murphy, and Prince enjoy. Pino implicitly takes each man’s wealth and notoriety as evidence that America has overcome its racist past, but disregards the patterns of marginalization, discrimination, and exclusion that Black Americans at large must overcome.

As such, Pino’s notion that his African-American heroes are “more than Black” recalls the racist stereotypes—enhanced by Ronald Reagan’s neoconservative rhetoric—that hardworking Americans are White, that lazy freeloaders are Black (or, if not, members of minority groups), and that Black Americans who succeed in their nation’s economic free-for-all transcend their racial background to become culturally White (in much the same way that ethnic Europeans from Ireland, Italy, Greece, and Poland who migrated to the United States in the late 19th and early 20th centuries came to consider themselves White as they assimilated into the dominant culture to fulfill the metaphor of America as an ethnic, racial, and cultural melting pot).75

Pino even alludes to the political complications of race by mocking Louis Farrakhan before telling Mookie to “get the fuck out of here” when the latter says that Pino wishes he were Black. Lee then cuts to perhaps Do the Right Thing’s most famous sequence (apart from its concluding violence), which his screenplay dubs the “Racial Slur Montage.”76 Five characters (Mookie; Pino; Stevie, a Latino man played by Luis Ramos; Officer Long, a White police officer played by Rick Aiello; and Sonny, the Korean co-owner of the block’s fruit-and-vegetable market played by Steve Park), without embarrassment or hesitation, hurl racial insults directly at the viewer as the image abruptly jumps from one to the next.

Mookie attacks Italian Americans as “You dago, wop, guinea, garlic-breath, pizza-slinging, spaghetti-bending, Vic Damone, Perry Como, Luciano Pavarotti, Sole Mio, non-singing motherfucker”; Pino abuses Black Americans as “You gold-teeth, gold-chain-wearing, fried-chicken-and-biscuit-eatin’, monkey, ape, baboon, big-thigh, fast-running, high-jumping, spear-chucking, 360-degree-basketball-dunking, titsun, spade, Moulan Yan”; and Officer Long, with startling ferocity, demeans Latinos as “Goya-bean-eating, 15-in-a-car, 30-in-an-apartment, pointed-shoes, red-wearing, Menudo, miramira, Puerto Rican cocksucker.”

This invective assaults the audience by placing each viewer in a firing line of crude stereotypes that doesn’t relent until the screen cuts to Mister Señor Love Daddy screaming, “You need to cool that shit out!” Lee’s inventive visual composition underscores the sequence’s simultaneous horror and comedy: The camera zooms from a medium shot toward each character’s face as he utters vile, racist words until reversing this movement when Love Daddy appears. The camera, in fact, remains stationary as Love Daddy rolls toward the radio station’s microphone in an office chair, ending in a medium close-up of his face as he rebukes the foregoing tirades.

Lee, by forcing Do the Right Thing’s audience to endure this racist vilification, reproduces the powerlessness that victims of racial stereotyping experience. The viewer’s inability to respond mimics the incapacity of racism’s victims to prevent their abuse in a brilliant cinematic strategy that interrupts the film’s ongoing narrative, but that, like similar episodes in Italian Neorealism, in French New Wave movies, and in Brechtian drama, distills the story’s themes into a disturbing, darkly humorous, and unforgettable sequence.

The Racial Slur montage also continues a tradition that Lee establishes in his first two movies—She’s Gotta Have It’s “dog sequence” and Half Pint searching for female companionship in School Daze—to illustrate how freely Lee dilutes classical Hollywood filmmaking to achieve stylistically clever sequences that function as micro-narratives within the movie’s overall story. The slur montage, indeed, transcends commentary to make Do the Right Thing’s audience complicit in the bigotry that its characters indulge, with Lee carefully positioning these epithets immediately after Pino’s and Mookie’s conversation not only to illustrate how prejudice cuts across different racial and ethnic (yet not gender) lines but also to suggest that Pino’s racism has communal roots that implicate his father.

Sal, who proudly tells Pino that “they [the block’s Black and Latino residents] grew up on my food,” seems perplexed by Pino’s vitriolic racism, yet, rather than telling his son that such beliefs are morally reprehensible, Sal instead appeals in roundabout fashion to the American melting-pot metaphor that elides the nation’s racial and ethnic differences: “I never had no trouble with these people. I sat in this window. I watched these little kids get old. And I seen the old people get older. Yeah, sure, some of them don’t like us, but most of them do.”

Sal’s response, along with his repeated references to “these people” and “you people,” suggests that Pino learned his bigotry, at least in part, from his father. Sal unthinkingly endorses White supremacy despite treating individual Black people—particularly Da Mayor and Jade—with fondness, even confessing to Pino that economic reasons explain his decision not move the business to his family’s home neighborhood of Bensonhurst (“there’s too many pizzerias already there”) more than his commitment to the block’s Black and Latino customers.

Sal’s patronizing attitude may not be as vicious as Pino’s noxious racism, but it helps explain why Pino behaves as he does. Lee addresses this possibility in several venues, including “Spike Lee’s Bed-Stuy BBQ,” his 1989 Film Comment interview with Marlaine Glicksman, by saying, “Pino didn’t pick up that stuff out of the air. Some of it had to have been taught him by his father, Sal.”77 This notion echoes Lee’s most mature statement about Sal’s bigotry, in his production journal’s 3 January 1988 entry: “This is the tricky thing. Like many people who have racist views, these views are so ingrained, they aren’t aware of them. We should see that in Sal. Basically he’s a good person, but he feels Black people are inferior.”78

Lee understands that American anti-Black prejudice is pervasive, invisible, and natural for its adherents, so identifying Sal as a genial, yet bigoted person offers a key insight into Do the Right Thing’s effectiveness. Neither the movie nor Lee portrays Sal as a reprehensible racist, but instead as a pleasant man who suppresses his bigotry to the point that he no longer recognizes it.

This all-too-common outcome causes Nelson George to see Sal as “represent[ing] every paternalistic member of an old-line New York ethnic group who has a kind but condescending view of his customers. That he feels they are childlike and irresponsible is apparent in his dealings with Da Mayor and Mookie, and in his refusal to include African Americans on his Wall of Fame.”79 George’s analysis insightfully summarizes both Sal’s behavior and Danny Aiello’s terrific performance in the role, with Aiello playing Sal as simultaneously kind, gruff, generous, condescending, good-humored, and overbearing to draw out the man’s paternalism.

Aiello finds so many nuances in Sal’s character that Sal becomes what Dan Flory calls a sympathetic racist. Flory’s splendid essay “Spike Lee and the Sympathetic Racist” notes that Lee creates such characters because “seeing matters of race from a nonwhite perspective is typically a standpoint unfamiliar to white viewers,” causing Lee to offer these audience members “depictions of characters . . . with whom mainstream audiences readily ally themselves but who embrace racist beliefs and commit racist acts.”80

These sympathetic racists, “by introducing a critical distance between viewers and what it means to be white,” permit Lee to make “a Brechtian move with respect to race,” namely offering White viewers a way “of experiencing what they have been culturally trained to take as typical or normative—being white—and see it depicted from a different perspective, namely, that of being black in America, which in turn removes white viewers from their own experience and provides a detailed access to that of others.”81

This perspectival shift is crucial to Lee’s African-American aesthetic. Caucasian viewers, according to Flory’s complex argument, “have trouble imagining what it is like to be African American ‘from the inside’—engaging black points of view empathetically—because they often do not understand black experience from a detailed or intimate perspective. It is frequently too far from their own experience of the world.”82 Flory, following Thomas E. Hill, Jr.’s and Bernard Boxill’s scholarship about American racial formation, writes, “this limitation in imagining other life possibilities may interfere with whites knowing the moral thing to do because they may be easily deceived by their own social advantages into thinking that such accrue to all, and thus will be unable to perceive many cases of racial injustice.”83

Do the Right Thing, indeed, presents Sal so approvingly that his racist behaviors—scorning Buggin’ Out’s use of the word brother when the latter requests Black celebrities on the Wall of Fame; threatening Buggin’ Out with a baseball bat to recall the Howard Beach incident; employing the phrases “these people” and “you people” to construct his customers as foreign others; and, most objectionably, heaping a torrent of racial abuse (“Turn that jungle music off! We ain’t in Africa!”; “Black cocksucker!”; “nigger motherfucker!”) on Radio Raheem and Buggin’ Out when they, near the film’s conclusion, loudly play “Fight the Power” to demand that Sal address their grievances—may not appear as bigoted as they are.

In fact, Danny Aiello, just like certain Do the Right Thing viewers, refuses to see Sal as racist, with his comments in St. Clair Bourne’s behind-the-scenes documentary Making “Do the Right Thing” revealing Aiello’s sense of Sal’s character. During a table reading of the movie’s screenplay, Aiello says, “I thought he’s not a racist. He’s a nice guy. He sees people as equal.” Later, Aiello elaborates his feelings about Sal: “Is he a racist? I don’t think so. But he’s heard those words so fucking often, he reached down. If it was me and I said it, I’m capable of saying those words, I’m capable, and I have said ’em, but I’m not a racist.”84

Aiello may believe that Sal makes the mistake of reaching into himself to find the most offensive words possible to use against Radio Raheem and Buggin’ Out rather than seeing this response as evidence of Sal’s suppressed racism, but Dan Flory argues that Aiello’s reaction embodies a specific type of racial allegiance that certain White viewers (and, in Aiello’s case, White performers) develop with characters like Sal, who don’t express openly racist behaviors despite holding unexamined racist beliefs:

The explanation for why many white viewers—and Aiello himself—resist seeing Sal as a racist might be formulated the following way. A white audience member’s understanding of a white character’s actions often accrues from a firm but implicit grasp of white racial experience, which presupposes the many ways in which the long histories of world white supremacy, economic, social, and cultural advantage, and being at the top of what was supposedly a scientifically proven racial hierarchy, underlay and remain influential in white people’s lives.85