Time Enough at Last

As Octavia E. Butler’s Kindred reaches television, revisiting its source novel reveals just how fabulous an author she was.

*Note to The Vestibule’s subscribers: The occasion for this review of Octavia Estelle Butler’s marvelous 1979 novel Kindred is that, nearly 17 years after her untimely death (on 24 February 2006, at the far-too-young age of 58), the first-ever mass-media adaptation of her oeuvre has finally debuted. Brought to life by the Obie Award-winning, Pulitzer Prize-nominated, and MacArthur Fellow-awarded playwright Branden Jacobs-Jenkins; a crackerjack writing staff; and a talented cast led by Mallori Johnson in the role of protagonist Dana James, the televisual Kindred premiered its inaugural season’s eight episodes on FX and Hulu on 13 December 2022.

I’ll have more to say about this notable, fascinating, and troubling adaptation of Butler’s best-known book sometime in 2023, but, for now, I’ll leave my thoughts about the novel here. They were initially prepared for my article “Remembering Octavia E. Butler,” which Washington University in St. Louis’s The Common Reader: A Journal of the Essay published on 28 August 2020.

Editors Gerald Early and Benjamin Fulton wisely cut my cumbersome, 10,000-word early draft down to size, but, in doing so, they excised my extended meditation upon Kindred’s place within the literary tradition of the American neo-slave narrative, as well as how favorably Kindred compares to perhaps this genre’s most famous example, Toni Morrison’s Pulitzer Prize-winning 1987 masterpiece Beloved.

I offer my appreciation of Butler’s equally terrific Kindred here not merely to piggyback off the publicity generated by the premiere of Jacobs-Jenkins’s adaptation, but to remind us all just how tremendous a novelist Octavia E. Butler was.

Please accept my warmest holiday greetings, as well as my wishes for a happy, healthy, and restful New Year.

All the best. — Jason

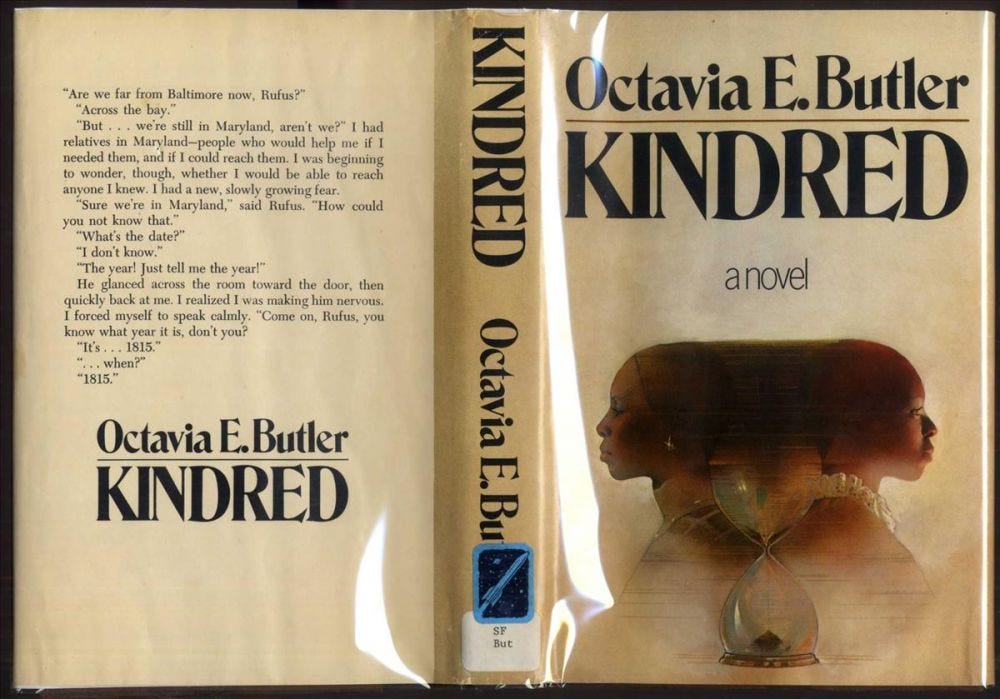

Kindred

Written by Octavia E. Butler

Published by Doubleday

Original Release June 1979

264 pages

ISBN 0-385-15059-8

$8.95

1. The Crying Game

I feel no shame in admitting that, upon learning Octavia E. Butler had died on 24 February 2006, I wept.

This reaction is unusual, at least for me, because no matter how much I admire public figures, their passing rarely moves me to tears. Since I did not personally know them, I cannot feel their loss as intensely as I do family and friends who have shuffled off this mortal coil. Perhaps this failure of empathy makes me a terrible person, perhaps it’s more common than I know, but I’ve never understood people who, treating cultural luminaries like treasured companions, get broken up by celebrity deaths.

Moreover, I regard as absurd those poor slobs who blubber openly while mourning the famous and the infamous, finding it easy to mock their melodramatic displays of grief. When, for instance, admirers of Steve Jobs, upon his 2011 death, thronged streets in cities around the world to hold aloft iPhones with cigarette-lighter graphics on their screens while proclaiming Jobs the singular genius of our time, I laughed in derision.

Who did they think they were, after all? Who did they think he was? Certainly not a beloved mother, father, sister, brother, or even favorite cousin. Although my Midwestern upbringing haunts me in ways I shall never overcome, I still believe, as did my parents and grandparents, that displaying one’s emotions in public this way is not merely bad form, but tantamount to making a spectacle of oneself.

And, as I was taught again and again during my youth, one should never do that.

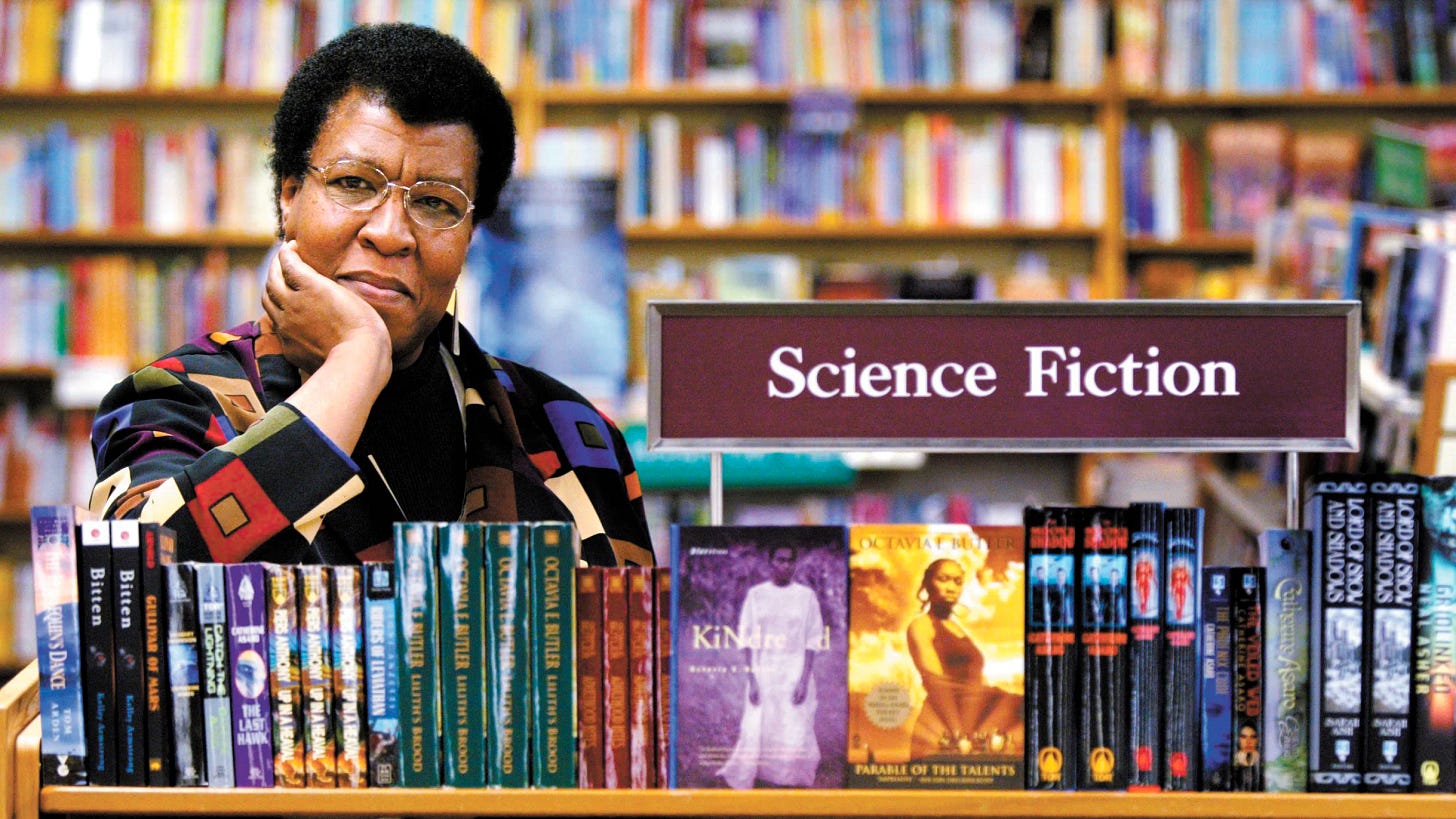

Yet Butler’s death provoked fulsome tears as I read the many online obituaries, remembrances, and tributes to this marvelous American author that appeared, with metronomic regularity, throughout that day. And, make no mistake, Octavia E. Butler was among the greatest American authors of the 20th Century, despite her name, at least in 2006, being excluded from this august group more frequently than it should have been. The intervening years have seen Butler’s work reclaimed by literary critics, scholars, and the reading public at large, but the fact remains that she was always terrific, even when too few people affirmed this judgment in the public square.

Some people, however, knew from the beginning. Specifically, Harlan Ellison—as problematic a cultural figure as 20th-Century America ever produced—knew. A brazen, pompous, reckless, arrogant loudmouth and scofflaw, Ellison—whose authorial talent is rapturously praised in certain quarters of literary fandom, especially science-fiction (SF) fandom—once said, “I don’t take a piss without getting paid for it”1 to underscore how no one, especially movie studios and television networks, should ever, ever, ever expect him to work for the love of the fans, for the beauty of art, and for the good of humanity—in other words, for free.

Ellison (Harlan, not Ralph, as if they could ever be confused) was such a cantankerous lout that, when Star Trek creator Gene Roddenberry and Star Trek producer Gene L. Coon dared to rewrite his teleplay for the now-classic episode “The City on the Edge of Forever”—that outing frequently (but incorrectly) judged the best Trek episode ever produced, where William Shatner’s Captain James T. Kirk and Leonard Nimoy’s First Officer Spock travel back to 1930s New York City to capture DeForest Kelley’s errant Dr. Leonard McCoy, who has changed history after leaping through a sentient time machine known as the Guardian of Forever, thereby allowing Kirk to romance Joan Collins’s brilliant and beautiful Edith Keeler—he (Ellison) hit the proverbial roof, never shutting up about how Roddenberry and Coon had perverted his work, even after both men had died and could no longer defend themselves, and even after the publication of his original, unaltered script proved (to me, at least) that Roddenberry, Coon, and Trek Story Editor Dorothy C. Fontana were correct to change Ellison’s overstuffed, overwrought, and dull early drafts.

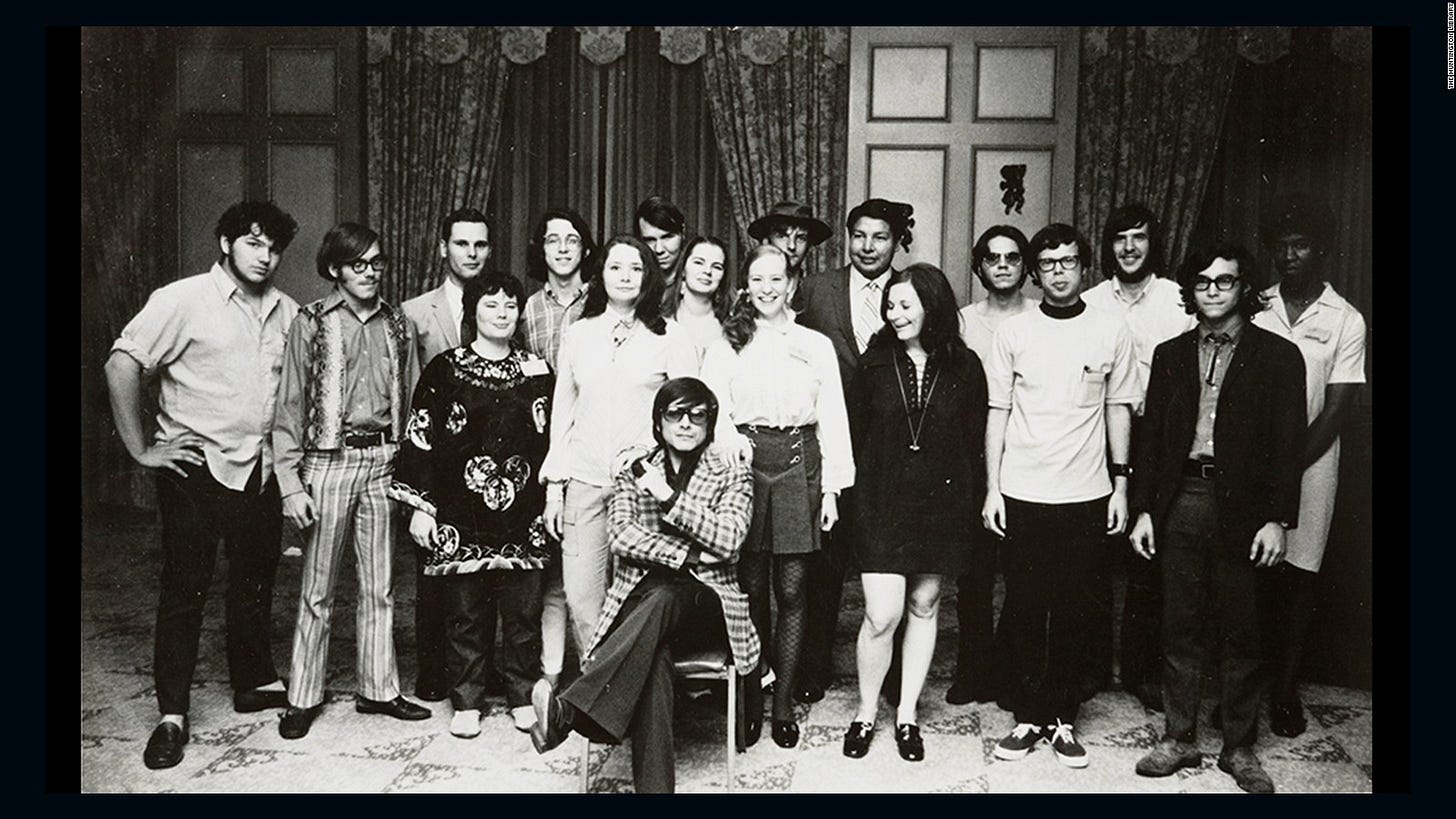

Despite Ellison, as this anecdote implies, being the classic enfant terrible who became the clichéd, hyper-masculine, self-parodying, no-good-sonuvabitch that popped up too frequently in midcentury American letters (picture Norman Mailer, shorter but more eloquent), Ellison knew good writing when he saw it, as his editorship of the award-winning 1967 SF anthology Dangerous Visions attests. No matter how personally objectionable Ellison’s behavior was, he at least helped launch Octavia E. Butler’s career by recognizing her talent when, in 1969, she enrolled in the Writers Guild of America’s (WGA’s) “Open Door” Workshop, a program run by Ellison that hoped to recruit talented Black and Latinx screenwriters.

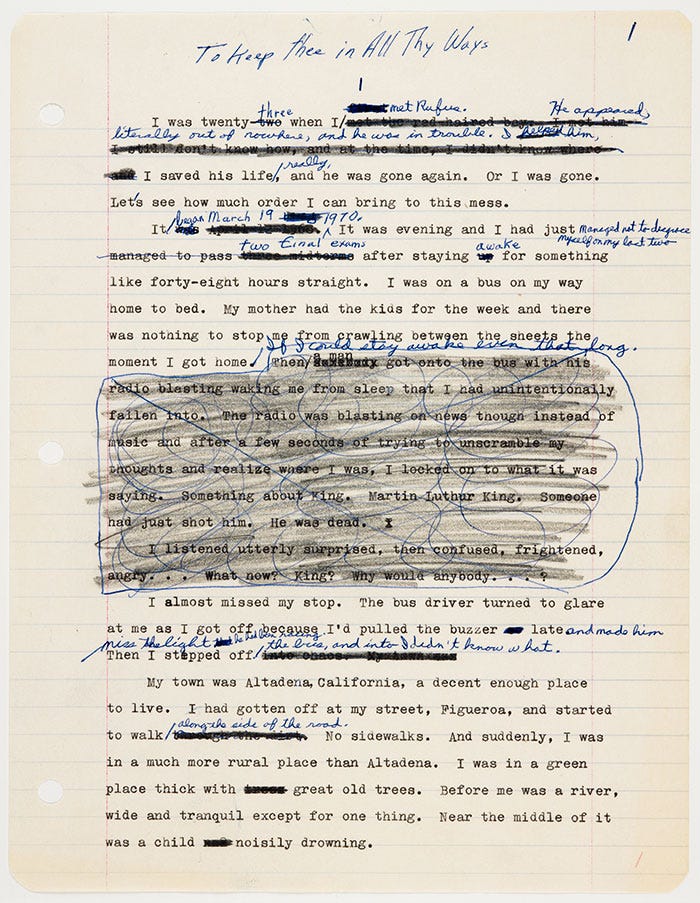

Impressed by Butler (who later said about her WGA experience, “I’m a very slow writer and screenplay writing, they really want it fast and any changes, they want that fast too. It’s not something that I’m real interested in”2), Ellison recommended her for the 1970 Clarion Science Fiction Writers’ Workshop—a writers’ camp founded in 1968 at Clarion State College (now Pennsylvania Western University, Clarion), for aspiring-but-unpublished science-fiction-and-fantasy (SFF) authors—where Ellison was set to become a star lecturer, teacher, and all-around gadfly.

Another of Butler’s teachers at the 1970 Clarion Workshop (which still exists, having become a legendary proving ground for new SFF writers) was Samuel R. “Chip” Delany—author of such terrific works as Babel-17, Dhalgren, and the superb short story “Aye, and Gomorrah . . .,” the final entry in Ellison’s original Dangerous Visions anthology—who would become Butler’s lifelong friend.

Ellison’s mentorship proved decisive for Butler’s authorial career, as he both encouraged her literary ambitions and purchased her short story “Childfinder” for publication in his newest anthology, The Last Dangerous Visions (the projected third and final volume of the Visions trilogy, announced in the opening pages of 1972’s follow-up effort Again, Dangerous Visions, but never to see the light of day because the prolific, yet mercurial Ellison—who died on 27 June 2018—never finished it, even after 46 years had elapsed).3

Despite this setback, Butler sold another story, “Crossover,” to Clarion, the workshop’s anthology publication. This beautifully rendered, extraordinarily brief tale of a depressed, alcoholic woman living and working on Skid Row, with no hope for the future, features a concluding twist that calls her entire life—and, indeed, the whole story’s basis—into doubt by ending on a splendid final sentence that forces the reader to question everything that’s come before, making “Crossover” not only an impressive debut for any author but also Butler’s first published work.

Then, no matter the rush of excitement these victories provoked, Butler didn’t sell another word for five years.

2. The Genre Game

Butler kept writing, which paid off when Doubleday released, to respectable reviews, her inaugural novel, Patternmaster, in July 1976. The first book published, but the last installment in the fictional chronology of her five-novel Patternist series (also known as the Wild Seed pentalogy), Doubleday issued the next two entries in this compelling (if disconcerting) cycle—1977’s Mind of My Mind and 1978’s Survivor—over the next two years. These fascinating novels tell the centuries-long story of how a society of dominant human telepaths known as Patternists evolves from two immortal Africans, Doro and Anyanwu, who select and seed children with special psychic abilities throughout successive generations until a group of networked telepaths emerges in 1970s California.

The Patternist series spotlights how themes of bondage, captivity, injustice, freedom, liberty, agency, and the myriad ways that Butler’s characters must, in their daily lives, navigate these historical forces remain so central to her fiction that they become inseparable from its frequently savage beauty. This declaration brings us, inevitably, to Butler’s 1979 masterpiece: her fourth novel, the simply titled, yet magnificently complex Kindred.

Again, the premise is irresistibly disturbing: a Black writer named Edana Franklin (Dana, for short), while moving into her new Los Angeles house with her new white husband, Kevin, on her 26th birthday (9 June 1976), experiences sudden dizziness, only to find herself mysteriously transported in time and space to the antebellum plantation of slave owner Tom Weylin, on Maryland’s Eastern Shore, where she sees Tom’s son, the child Rufus Weylin, drowning in a river.

Dana saves Rufus from the water, only to be accosted by his mother, Margaret, right before Tom points a rifle in Dana’s face and cocks the trigger. Dana, frightened for her life, becomes dizzy again, then finds herself back in her 1976 home, with the perplexed Kevin telling her she disappeared for a few seconds despite the fact that, from Dana’s perspective, several minutes have elapsed.

Thus begins a pattern. Whenever Rufus finds himself in mortal danger, Dana is pulled from 1976 California back to the Weylin plantation in whichever year Rufus requires assistance (1815, then 1819, then 1824, but always moving forward in time). Dana continues to save the progressively crude and cruel Rufus from disaster because he will one day marry Dana’s ancestor Alice Greenwood and, in 1831, father a girl named Hagar, Dana’s great-great grandmother.

This insidious, ingenious plot condemns Dana, during her trips to antebellum Maryland, to live as an enslaved person on the Weylin plantation despite the feminist consciousness and personal independence she’s developed during her 1976 life. It also forces Kindred’s readers to reckon with the violence, terror, and grinding oppression of American chattel slavery, as well as the strength, endurance, and dignity of its enslaved characters, whom Butler develops in such rich detail that they remain indelible after only a single reading.

Butler, with Kindred, writes a terrific example of what Bernard W. Bell, in his noteworthy 1987 study The Afro-American Novel and Its Tradition, calls the “neoslave narrative” and into which Ashraf H.A. Rushdy—first in a 1997 Oxford Companion to African American Literature article and then again, two years later, in his masterful 1999 monograph Neo-slave Narratives: Studies in the Social Logic of a Literary Form—inserts a hyphen to produce the term “neo-slave narrative,” a present-day fictional reconstruction of “the peculiar institution” of American chattel bondage that, at its best, helps readers understand the experience of enslaved Americans in ways that approach, and occasionally surpass, the actual slave narratives of people such as Harriet Tubman, Harriet Jacobs, Mary Prince, Olaudah Equiano, Solomon Northup, and, most famously, Frederick Douglass.4

Among the neo-slave narrative’s best-known examples before Kindred’s 1979 publication are Margaret Walker’s Jubilee (1966) and Ernest Gaines’s The Autobiography of Miss Jane Pittman (1971), two novels that Bell analyzes at length in The Afro-American Novel and Its Tradition. William Styron’s The Confessions of Nat Turner famously won the Pulitzer Prize in 1967, yet generated significant controversy over its portrayal of Turner as a bumbler who fantasizes about sexually assaulting white women and its other deformations of Turner’s heroism.

Styron’s novel, despite its acclaim, remains a mediocre effort that cannot stack up against the excellence of Walker’s Jubilee and Gaines’s Miss Jane Pittman, with Butler’s entry in this literary genre being a marvelous and important exemplar too frequently unacknowledged as a forerunner to the most famous neo-slave narrative of all, Toni Morrison’s superb 1987 novel Beloved, which, by winning the Pulitzer Prize twenty years after Styron’s The Confessions of Nat Turner, cleansed the American literary palate of any remaining distaste to became a stunning achievement in its own right.

Beloved is so good that it moved novelist and book critic John Leonard to conclude his admiring 30 August 1987 Los Angeles Times review by writing these lines: “Beloved belongs on the highest shelf of American literature, even if half a dozen canonized white boys have to be elbowed off. The thing is, now I can’t imagine American literature without it. Without Beloved, our imagination of the nation’s self has a hole in it big enough to die from.”5 Encomia do not glow much brighter than this statement, to say nothing of Leonard’s judgments that “Toni Morrison’s masterwork is a ghost story about history”6 and “Morrison does a thousand wonderful things in her circling”7 through the physical, psychological, political, and personal complexities of surviving slavery.

All true, I would add, but everything that Leonard says about Beloved he could have said about Kindred had he ever read Butler’s novel. As monumental an accomplishment as Beloved is for Morrison, Kindred is for Octavia E. Butler and, indeed, for American literature. Butler’s novel should sit on the same shelf as Morrison’s triumph, indeed to its left to indicate that Kindred arrived first, but to the right of Jubilee and Miss Jane Pittman in a chronological ordering of the best American neo-slave narratives published during the 20th Century, a shelf that should also house Alex Haley’s Roots: The Saga of An American Family (1976), Ishmael Reed’s Flight to Canada (1976), and Sherley Anne Williams’s Dessa Rose (1986).

3. The Terrains of Time

Kindred, to state the matter plainly, is every bit as good as Beloved, but not at all the same despite playing in similar generic sandboxes. Morrison’s novel famously shuns conventional novelistic structures and precepts by 1) refusing to number its chapters; 2) freely mixing narration, dialogue, internal monologue, and landscape description into a kaleidoscopic storyline that sometimes explodes the notion of narrative into blasted bits; 3) including imagery so phantasmagorical that readers occasionally become lost in the flood of onrushing words; 4) rotating each chapter’s point of view through a different character except when it merges multiple characters’ viewpoints into a single chapter; and 5) so artfully playing with its reader’s expectations that classifying Beloved as a novel, while formally correct, always seems to fall just shy of accurate description.

Beloved, therefore, strikes knowing readers as exemplary postmodern fiction whose ghostly neo-slave narrative burrows its way inside its characters’ multivalent experiences as well as any book in the American literary canon.

Kindred, by contrast, 1) titles (rather than numbers) its chapters even while dividing those chapters into consecutively numbered sections; 2) alternates narration, dialogue, internal monologue, and landscape description in identifiable patterns; 3) evokes images of startling verbal precision (the description of Alice Greenwood’s father being whipped, for instance, is so vivid that it remains unforgettable to anyone who reads it); and 4) focalizes most chapters and sections through Dana’s consciousness, although Alice, Rufus Weylin, Kevin Franklin, and a few other characters sometimes hijack stretches of narration for themselves.

Kindred, at first blush, might appear a more conventional neo-slave narrative sharing more in common with, say, Jubilee than it does Beloved. Even if Kindred contains identifiable postmodern tropes and effects, particularly the manner by which its narrative whipsaws Dana through time, Butler’s novel seems less abstruse than Beloved, at least upon first reading.

And yet, like John Leonard with Morrison’s magnum opus, I cannot imagine American literature without Butler’s.

Kindred’s power emanates from its fantastic premise, in which a 20th-Century Black woman involved in an interracial marriage must come to terms with slavery in the most literal manner. Dana must learn to live as an enslaved person when she returns to antebellum Maryland for increasingly longer stretches of time, with Butler powerfully depicting the psychological, physical, and spiritual compromises that this journey forces onto her protagonist, who nonetheless refuses to be objectified by any member of the Weylin family despite realizing that, in order to survive, she cannot resist her bondage or her bondsmen in the forthright manner she would prefer.

Dana, in other words, cannot simply attack, injure, or kill the white men and women whom she encounters, for she soon recognizes how pervasive is the generational system of racist terrorism that American chattel slavery was, a truth that Kindred depicts so well and so candidly that certain readers (including some of my own students) vow never to read it again.

A few examples demonstrate how well Butler constructs Kindred. After witnessing Tom Weylin so severely whip “a field hand for the crime of answering back”8 that Dana realizes this punishment “served its purpose as far as I was concerned. It scared me, made me wonder how long it would be before I made a mistake that would give someone reason to whip me,”9 she comes upon a group of Black children playacting a slave auction, with a young boy named Sammy standing on a tree stump determining imaginary values for his friends. When a little girl protests that her “price” of two hundred dollars is too low, Dana “turned and walked away from the arguing children, feeling tired and disgusted.”10

She cannot blot these experiences and images from her mind, later commenting, “The ease seemed so frightening. Now I see why.”11 When asked precisely what she means, Dana’s response offers a chilling insight that readers may wish to protest, but that Kindred’s vicious logic makes nearly impossible to deny: “The ease. Us, the children. . . I never realized how easily people could be trained to accept slavery.”12

When Dana is later whipped and beaten by Tom Weylin for teaching some of the plantation’s residents to read, she endures physical and psychological pain that troubles her for the remainder of Kindred’s narrative. Although she never exactly accepts slavery, Dana realizes that her fellow plantation dwellers never do, either, so she comes to hold them in the highest regard for surviving a system that never succeeds in dehumanizing them despite taking every opportunity to degrade, demean, and debase them. Their courage—alongside Butler’s success in detailing their relationships and their daily lives on the Weylin plantation—makes Kindred a terrific, yet heartbreaking novel to encounter.

Despite Dana time travelling to Maryland’s Eastern Shore (notably, the same area near Talbot County where Frederick Douglass was born and raised, as well as Dorchester County, where Harriet Tubman was reared), Butler refused her entire career to call Kindred science fiction, instead terming it a “grim fantasy”13 while encouraging her publishers to do the same.

Butler, moreover, tells Lisa See in a 1993 Publishers Weekly interview that the inspiration for Kindred came from her days at Pasadena City College, when a friend and fellow student involved in the Black Power Movement “who could recite history but didn’t feel it . . . said, ‘I wish I could kill all these old black people who are holding us back, but I’d have to start with my own parents.’ Well, it’s easy to fight back when it’s not your neck on the line.”14

Mentioning to Charles Henry Rowell during a 1997 interview for the literary journal Callaloo that “I’ve carried that comment with me for thirty years,”15 Butler’s empathy for her enslaved ancestors contradicted her friend’s attitude so forcefully that she wished one day to publish a book refuting his wrongheaded perspective: “So I wanted to write a novel that would make others feel the history: the pain and fear that black people had to live through in order to endure.”16

On this score, Kindred remains a smashing success, a signature contribution to American letters, and, yes, a masterpiece no less praiseworthy than Toni Morrison’s Beloved. Bear in mind, dear reader, that tears sprang to my eyes when Morrison’s death was announced on 5 August 2019, yet her work should not obscure Butler’s. Morrison, in her collected literary reviews and essays, never mentions Butler, but each woman’s writing so congenially complements the other’s that a comparative study of their fiction has become a so-far-unmet scholarly necessity.

As if called upon to correct this oversight by ensuring that Kindred remains alive in America’s literary memory, Harlan Ellison, when asked to write a blurb for Butler’s fourth novel, lauds his protégé’s writing by offering a panegyric every bit as passionate as John Leonard’s Los Angeles Times tribute to Morrison:

Kindred is a story that hurts: I take that to be the surest indicator of genuine Art. It is an important novel, filled with powerful human insight and the shocking impact of the most commonplace experiences viewed in a new way, and it demands that once begun, the reader continue till it has done its work on the heart and mind and soul. Octavia Butler is a writer who will be with us for a long, long time, and Kindred is that rare, magical artifact . . . the novel one returns to, again and again, through the years, to learn, to be humbled, and to be renewed. Do not, I beg you, deny yourself this singular experience.17

If this elegy seems unrestrained in its veneration of Octavia E. Butler, only two comments are necessary. First, such excess typifies Ellison’s boosterism of writers whom he admires and champions, but since his enthusiasm helped Butler become a published author, I cannot gainsay this appraisal’s tone or temper.

And second, despite disagreeing with Ellison about so much during his long career, I cannot, in this instance, deny his wisdom. Every clause is correct, making Ellison’s fervor for Kindred (and its author) spot-on, proving that even scofflaws get it right every now and then.

So, my friends, do yourself a favor by reading Kindred at the earliest opportunity.

Yes, you’ll be humbled.

You’ll be horrified, too.

Yes, you’ll be renewed.

And, without question, you’ll be impressed.

Octavia E. Butler was—no, is—one of America’s greatest literary lights, so reckoning with Kindred will enrich your humanity in ways so large and small, so obvious and subtle, that you’ll be astounded by the journey on which Butler conducts you.

That’s remarkable, and not to be missed, and all that needs be said about the tour de force that is Kindred.

NOTES

Ellison makes this declaration in Erik Nelson’s 2008 biographical documentary, Dreams with Sharp Teeth. Relevant footage from Nelson’s film, including Ellison’s now-famous quote, can be seen in this YouTube clip: “Harlan Ellison—Pay the Writer.”

Jelani Cobb, “Interview with Octavia Butler (1994),” Conversations with Octavia Butler, edited by Conseula Francis, University Press of Mississippi, 2010, p. 54.

This interview first appeared on Cobb’s personal website, jelanicobb.com.

The best, most thorough, and most illuminating analysis of why The Last Dangerous Visions never saw publication is, without question, Christopher Priest’s damning (to Ellison) The Book on the Edge of Forever: An Enquiry into the Non-Appearance of Harlan Ellison’s “The Last Dangerous Visions” (Fantagraphics Books, 1994).

Although this book’s cover bears the subtitle The FACTS, the FIGURES, and the DELUSIONS Behind HARLAN ELLISON’s Never-Published Anthology, this alternate heading doesn’t appear on the title page, which instead prints the subtitle exactly as this note’s first paragraph does.

Priest’s online version of this text (titled The Last Deadloss Visions) includes additional comments made after his book’s publication.

Publication information for all three sources follows: Bernard W. Bell, The Afro-American Novel and Its Tradition, University of Massachusetts Press, 1987. Bell coins the term “neoslave narrative” on Page 246, later defining this genre as “residually oral, modern narratives of escape from bondage to freedom” on Page 289.

Ashraf H.A. Rushdy, “Neo-slave Narrative,” The Oxford Companion to African American Literature, edited by William L. Andrews, Frances Smith Foster, and Trudier Harris, Oxford University Press, 1997, pp. 533-35, along with The Cambridge Companion to the African American Novel, edited by Maryemma Graham, Cambridge University Press, 2004, pp. 87-105.

Ashraf H.A. Rushdy, Neo-slave Narratives: Studies in the Social Logic of a Literary Form, Oxford University Press, 1999.

John Leonard, “Beloved by Toni Morrison,” Los Angeles Times, 30 August 1987, https://www.latimes.com/archives/la-xpm-1987-08-30-bk-4702-story.html.

Ibid.

Ibid.

Ibid., pg. 92.

Ibid., pg. 99.

Ibid., pg. 101.

Ibid.

Lisa See, “PW Interviews: Octavia E. Butler,” Conversations with Octavia Butler, edited by Conseula Francis, University Press of Mississippi, 2010, pg. 40.

See’s interview with Butler first appeared in Publishers Weekly, 13 December 1993, pp. 50-51.

Ibid.

Charles H. Rowell, “An Interview with Octavia E. Butler,” Conversations with Octavia Butler, edited by Conseula Francis, University Press of Mississippi, 2010, pg. 79.

Readers may also find Rowell’s interview with Butler in Callaloo, vol. 20, no. 1, Winter 1997, pp. 47-66.

See, Conversations with Octavia Butler, pg. 40.

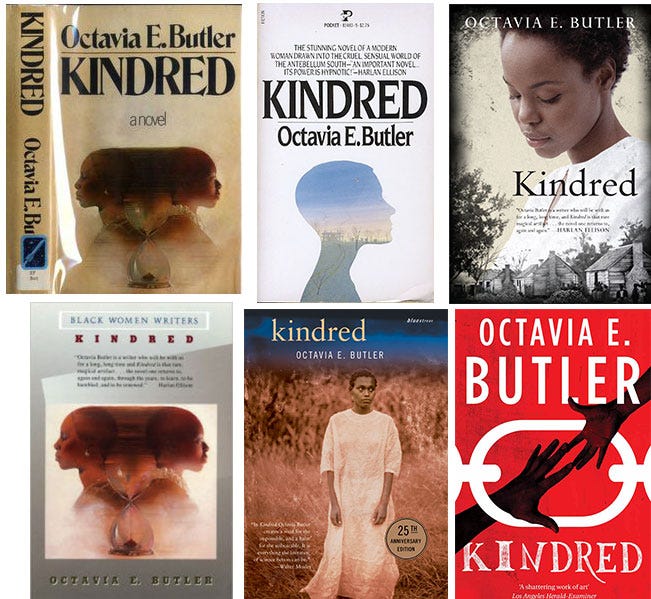

Harlan Ellison, Kindred cover, Beacon Press, 1988. Ellison’s blurb first appeared on this reissued edition of Kindred and has appeared on the cover (or in the opening pages) of most editions published since.

Ellison seems to have prepared this appreciation specifically for later reprints of Kindred since his collected nonfiction writings omit it. His full blurb begins with the following lines:

Like emotion that uplifts and enriches, like exquisite music or the taste of some special candy remembered from childhood, I never wanted Kindred to end. It overwhelmed me, dominated me, drew me on page after page. To express my total admiration and wonder for the originality of this surpassingly compelling novel, I am driven to a despised cliché: I could not put it down! It is a book that simply will not be denied; its power is hypnotic.

Please see Ellison’s complete appraisal on the website LitLovers’s full Kindred page.