Star Trek: Picard

“Watcher”

Season 2, Episode 4

Teleplay by Juliana James & Jane Maggs

Story by Travis Fickett & Juliana James

Directed by Lea Thompson

Starring Patrick Stewart, Orla Brady, Michelle Hurd, Alison Pill, Jeri Ryan, and Santiago Cabrera

Guest Starring Ito Aghayere, Oscar Camacho, Leif Gantvoort, Isabella Meneses, Sol Rodriguez, Kirk R. Thatcher, and Annie Wersching

Special Guest Star John de Lancie

45 minutes

Original broadcast 24 March 2022

1. Looking Out

As Star Trek: Picard Season 2 enters midlife, it shows no signs of slowing down, nodding off, or bottoming out. Its fourth episode, “Watcher,” may be the shortest so far, but this installment’s many plot points, character moments, and action sequences produce a narrative effect that co-writers Juliana James & Jane Maggs, authoring their script from a story that James concocted with consulting producer Travis Fickett, design to guarantee their audience’s strict attention.

Even more salutary is how Fickett, James, and Maggs—as well as their boss, showrunner Terry Matalas—trust their viewer’s intelligence enough to complicate Season 2’s serialized story by adding details, events, and revelations that extend its narrative sprawl beyond the boundaries of its first three entries, which have journeyed from the Federation’s confrontation with a never-before-seen Borg Queen (“The Star Gazer”) into a dystopian timeline arranged by John de Lancie’s cosmic trickster Q that finds our protagonists enduring the fascistic Confederation of Earth’s cruelty (“Penance”) before travelling into this hellish world’s past, namely the year 2024, where they hope to prevent the Confederation from coming to exist (“Assimilation”).

“Watcher,” in other words, keeps events moving so quickly that it produces whiplash in audiences that have little choice but to pay heed. Viewers find themselves whipsawed between three distinct storylines that, while thematically interwoven, move in different directions and at variable tempos. Advancing Season 2’s story this way depends upon several elements, especially precise timing, even if the errant hand of coincidence intrudes to ensure that “Watcher” unfolds as it should (and it must) if its outcomes are to be believed.

How else to explain Admiral Jean-Luc Picard (Sir Patrick Stewart) and Dr. Agnes Jurati (Alison Pill) determining that they and their La Sirena compatriots Raffi Musiker (Michelle Hurd), Seven of Nine (Jeri Ryan), and Cristóbal Rios (Santiago Cabrera) have arrived in Earth’s past, on 12 April 2024, with only three days to prevent a temporal alteration that they haven’t yet identified? Why not three weeks, three months, or three years?

The answer, of course, is that Matalas and his writing team wish to increase the urgency afflicting Picard’s characters no less than its audience even if the official explanation is that Annie Wersching’s Borg Queen, having pinpointed the “temporal recision” that Picard and company must repair or prevent, lands them close enough to this occasion to stop it without ruining history even further. An alternative possibility is that the Queen is unable to calculate their landing date as precisely as necessary, thereby leaving the crew precious little time to engineer and execute their plan to save the future by repairing the past.

Your tolerance for these concurrences probably varies depending upon your personal definition of the related, but distinct, concepts of believability, plausibility, and realism, as well as how far you wish to indulge the suspension of disbelief that Samuel Taylor Coleridge discusses in his 1817 book Biographia Literaria. Accepting Picard’s version of time travel in “Watcher” requires some fancy temporal footwork, after all, no matter how much disbelief you suspend, so determining how far any viewer might go in this regard isn’t limited to Coleridge’s famous analysis of how fiction functions.

J.R.R. Tolkien, for instance, argues in his 1947 essay “On Fairy Stories” that narratives diverging from what Tolkien calls “Primary Reality”—the world we all know and endure hour by hour and day by day—develop “the power of giving to ideal creations the inner consistency of reality.”1 This power permits these tales to become what Tolkien considers “the most nearly pure . . . and most potent” form of Art (a term that Tolkien almost always capitalizes), otherwise known as Fantasy (again, nearly always capitalized) and its notional cousin, the fantastic.2

Tolkien restricts the best fantasy to the printed page rather than the visual arts (such as paintings) and the dramatic arts (such as stage plays), yet he reserves to fantasy the immense power to make a “Secondary World . . . commanding Secondary Belief” in its premises.3 These precepts may differ from the rules governing our primary world, but, if they remain internally consistent, they produce an aesthetic response of total belief, if not immersion, in the secondary world created by the author’s words. This achievement permits readers to consider, to review, and to see their own world from the perspective of another, contingent space that, being simultaneously real and unreal, not only provokes deep reflection but also deep pleasure, or what Tolkien calls “a piercing glimpse of joy.”4

Joy is an acutely personal experience, so your mileage may vary when reading a fairy tale, attending a play, or watching a Star Trek episode. Even so, for nearly one century now critics, reviewers, and scholars have employed a version of Tolkien’s formulation—that fantastical fiction estranges us from quotidian reality just enough to create useful vantage points from which to regard that reality’s perimeters and parameters—to describe how science fiction (or any story that falls under the rubric of speculative fiction) operates. Tolkien wasn’t the first person to enunciate this idea, which we can trace (in whole or in part) back to thinkers including Aristotle and Horace, but “On Fairy Tales” remains a persuasive explication of the power that ostensibly unrealistic stories hold over us thanks to Tolkien’s clear and engaging prose, as well as his spirited defense of fantasy as a worthwhile product of the human imagination.

The Star Trek franchise, to my mind, is a marvelous example of “the fantastic” in Tolkien’s sense of this term even if Trek cannot be classified as fantasy in the same way that The Hobbit and The Lord of the Rings can. Despite their close connections, Tolkien describes the fantastic as a broader critical category than the genre of fantasy (particularly the high fantasy that made Tolkien’s literary reputation), which leaves us to judge any fantastic work’s merit based upon a whole host of criteria, including its internal consistency, its expressive fineness, and how plausibly it obeys the premises of the world created for its audience.

The coincidences inscribed in Picard’s approach to time travel, therefore, are more or less permissible depending upon how strongly you accept happenstance as a force that exists in our daily lives. For myself, such correspondences are real, if rarer in actual life than in fiction. Put another way, if my loves of the fantastic, of science fiction, and of Star Trek have taught me anything, it’s that coincidence, happenstance, synchronicity, or whatever term you employ isn’t merely shared by most fantastic tales, but remains foundational to their narrative existence.

The fact that Picard’s crew must solve a problem in three days establishes an internal reality, as well as a suspense-generating clock, that I buy even if “Watcher” marshals its events into a sequence that, should it happen any other way, would fall to pieces with barely a moment’s hesitation.

These conveniences don’t bother me since Fickett, James, and Maggs deploy them to create a narrative space whose thematic concerns and political commentary resonate with “Watcher’s” three predecessors while ruminating about memory, identity, and reality from unexpected vantage points. They accomplish these goals by creating an alternate version of Whoopi Goldberg’s Guinan, one of Trek’s most venerable characters, in a move that refreshes our perceptions of her, of Star Trek: Picard, and of the man at its center.

2. Listening In

When Picard and Jurati determine the coordinates for the “watcher” of this installment’s title, a person whom, the Borg Queen says, can help them prevent the timeline alteration that will create the Confederation’s authoritarian future, Picard beams there to discover that he’s returned to the Forward Avenue location of Guinan’s Los Angeles bar first seen in “The Star Gazer.” Its rundown 2024 neighborhood resembles the Sanctuary District that Raffi and Seven encounter in “Assimilation,” full of unhappy people living marginal existences among streets full of trash and misery. The front of 10 Forward Avenue looks nearly the same as it did in the 25th Century, while the interior bears a more rough-and-ready, dive-bar aesthetic than its future version, but the most surprising difference is Guinan herself.

Viewers like myself expecting—and even hoping—to see Goldberg again despite her name not appearing in this episode’s opening credits are as surprised as Picard to see Ito Aghayere’s younger version emerge from a back room to tell Picard that he must leave since she’s about to close the bar for good. Coincidence, thy name is Picard, so even if the good admiral catching Guinan just as she’s leaving her place of business for the final time seems like a whopper, it’s small potatoes compared to seeing this spikier version of the woman we’ve known as a serene and comforting presence (except when confronting Q or the Borg, two forces whom Guinan and/or her species, the El-Aurians, cannot abide).

Aghayere’s Guinan dresses in 21st-Century American clothing rather than the flowing, floor-length dresses that Goldberg’s version prefers; leaves her beautifully arranged hair uncovered rather than wearing the fantastic hats for which Guinan’s famous (so terrific are they that the late-great SF writer Ursula K. Le Guin praises them in a 14 May 1994 TV Guide article5 written to commemorate Star Trek: The Next Generation’s excellence just days before the broadcast of its series finale, “All Good Things . . .”); and isn’t afraid to brandish a shotgun at Picard, a man she doesn’t recognize despite their long association in what I’ll call, after Tolkien, Star Trek’s prime timeline.

Recasting this role prevents Matalas and his production crew from employing de-aging makeup, software, and filming techniques to make Whoopi Goldberg resemble her younger self, which seems a wise decision considering the mixed results achieved by Lucasfilm in presenting the younger, de-aged version of Mark Hamill’s Luke Skywalker in The Mandalorian (2019-Present) and The Book of Boba Fett (2021-2022). Even so, finding the right performer is crucial to maintaining continuity and consistency with what we know of Guinan, although bringing a new actor to the part mandates taking Guinan in new and unforeseen directions. Otherwise, why go down this road at all? As such, I’m pleased to report, dear reader, that Ito Aghayere is a fabulous choice on all fronts, while Juliana James & Jane Maggs write this 21st-Century Guinan so differently than we anticipate that viewers must adjust to her presence just as Picard does.

Placing audiences in the same position as Picard’s leading man smartly unsettles our expectations while knocking us off base just enough to make Young Guinan a familiar and foreign presence all at once. Guinan not remembering Picard certifies, for any doubters, that Picard Season 2’s mode of time travel takes up where Matalas & Fickett’s SyFy Channel adaptation of Terry Gilliam’s 12 Monkeys left off, with time—or Time, a living force in the 12 Monkeys-verse—not obeying laws of strict causality, but instead following principles akin to chaos theory that allow historical transformations to alter every aspect of time before and after the changed event.

As fans of Star Trek: The Next Generation (TNG) well know, Guinan’s earliest meeting with Picard occurs in 19th-Century San Francisco during the “Time’s Arrow” two-parter that spans TNG’s fifth and sixth seasons. When Brent Spiner’s Commander Data is accidentally transported there while investigating the mystery of his head being discovered inside a cavern beneath the Presidio by 24th-Century archaeologists who determine that this impossible relic has rested there for nearly 500 years, Picard and most of U.S.S. Enterprise-D command crew return to the past, only to discover Guinan attending high-society soirees and hobnobbing with the likes of Mark Twain (Jerry Hardin) during an extended visit to Earth that proves El-Aurians to be much longer lived than previously suspected.

This devilishly clever time-travel story (written by Joe Menosky, Michael Piller, and Jeri Taylor) puts multiple predestination paradoxes into play while revealing how Guinan and Picard first met, at least from her perspective, since Picard’s first encounter with Guinan won’t occur, from his viewpoint, for five centuries. Internal consistency always becomes tangled in time-travel stories, but Young Guinan not recognizing Picard in “Watcher” means that the single change Q makes to Earth’s history (when, at the conclusion of “The Star Gazer,” he moves Picard and his La Sirena crewmates into the Confederation’s terrible reality) reverberates in all temporal directions to erase many details of their lives. The Confederation, as Picard realizes in “Penance,” is neither an alternate history nor a parallel reality, but instead their own world deformed by the alteration Q makes in 2024.

As such, everything that happened before this point in Trek’s prime timeline changes. Since Picard never commanded the Enterprise-D in this version of Trek’s history, he never travelled back to 19th-Century San Francisco to meet Guinan, who may still have visited Earth at that early date but who never encountered Picard, Starfleet, or the Federation, the last two never having existed anyway. Young Guinan, indeed, is so disgusted by humanity’s shabby treatment of their planet that, when Picard ambles into 10 Forward Avenue, she wishes to leave not only her bar but Earth itself. Picard pleads with her, in the best Star Trek fashion, to remain optimistic about humanity’s potential, but we soon realize that seeing the world become a polluted, fractious, and cruel place so sickens Young Guinan that she no longer wishes to watch human beings destroy themselves.

Aghayere plays these scenes with an affecting, surprising, and even bracing weariness. Young Guinan, moreover, retches when Picard repeats words that Goldberg’s older and wiser 25th-Century version of her character says to him in “The Star Gazer,” triggering a condition known as Af-Kelt, or time sickness, that reminds careful viewers of a similar condition afflicting James Cole (Aaron Stanford) and other time travellers throughout Matalas & Fickett’s 12 Monkeys. Since that program’s approach to time travel so closely follows Star Trek’s (and especially TNG’s), “Watcher” continues to participate in a pleasant feedback loop with 12 Monkeys. These mutual inspirations are tangled, yet consistent with the rules established in each, so Young Guinan having no memory of Picard isn’t the continuity error that some fans have claimed, but instead the logical outcome of the temporal mechanics to which Picard and 12 Monkeys subscribe.

As such, Q’s intervention in both Picard’s and Picard’s affairs hearkens back to the anti-time anomaly whose mysterious formation drives the action of “All Good Things . . .” and whose effects propagate backward along the spacetime continuum, threatening to disrupt the formation of all life on Earth in the Trek franchise’s nastiest-ever predestination paradox. I’m glad James & Maggs don’t devote much dialogue to explaining these mechanics (as I just have), instead allowing their audience to infer what’s happening from Picard and Young Guinan’s conversation, whose implications are both head-spinning and mind-expanding to ponder. Such intellectual gymnastics are perhaps the happiest consequences of telling a good time-travel narrative, which “Watcher” delivers in spades.

3. Keeping Up

This episode’s most fascinating aspect sees Young Guinan commenting upon the state of our world, particularly 21st-Century American society’s rapacious economic inequality and maddening political sclerosis, in unusually direct terms that recall Star Trek: Deep Space Nine’s unforgettable Season 3 two-parter “Past Tense.” Guinan caustically condemns the indifference, cruelty, and white supremacy running rampant through 2024 Los Angeles: “This place is a pressure cooker. You know they’re actually killing the planet? Truth is whatever you want it to be. Facts aren’t even facts anymore. A few folks have enough resources to fix all the problems for the rest, but they won’t because their greatest fear is having less.”

These jabs at post-Trump America are refreshing to hear, at least for me. Rather than pulling punches, Star Trek: Picard confronts the most distressing aspects of contemporary life, with Young Guinan telling Picard that she’s decided to depart Earth before these problems grow worse. The verbal fencing between Young Guinan’s disillusioned, even jaundiced perspective and Picard’s soulful faith in humanity’s potential is fascinating to watch thanks to Ito Aghayere’s and Patrick Stewart’s terrific work in these scenes, helped by director Lea Thompson keeping the camera focused on each performer’s face.

This choice allows the audience to study small, but significant, changes in expression that tell their own story, with Aghayere slowly softening her features’ grim hardness into more relaxed poses that wordlessly indicate how Young Guinan still wishes to believe Picard’s assurances about a better future being possible even if bitter experience teaches her otherwise. Aghayere’s and Stewart’s easy chemistry recalls the best interactions between Picard and Whoopi Goldberg’s Guinan, yet brings a disturbing spin to this relationship that’s not easily shaken off or ignored.

When Picard tells Young Guinan that she must be patient with humanity, she replies, “You know who has the luxury of patience here? Someone who looks like you and not like me. This world had more potential than I’d ever imagined. But the hatred here? It never ends, it just swaps clothes. This century? It took off a hood and put on a suit. You say change is coming? Well, it’s too damn slow and the cost way too high. And being forced to watch it hurts.”

This indictment of 21st-Century American society is tough, abrasive, and accurate, so much so that it recalls Julian Bashir’s (Alexander Siddig’s) appalled response to San Francisco’s Sanctuary District in “Past Tense, Part I.” As Benjamin Sisko (Avery Brooks) reminds Bashir there, “They made some ugly mistakes, but they also paved the way for a lot of the things we now take for granted,” a role that Picard takes up in “Watcher” by pleading with Young Guinan to remain on Earth rather than abandoning it to hopelessness.

Picard’s words are practical insofar as he wishes to locate the Watcher that can assist him, but their political dimensions echo Jurati’s, Raffi’s, Rios’s, and Seven’s experiences in “Watcher’s” other storylines. Rios, arrested by Immigration and Customs Enforcement Officers at the conclusion of “Assimilation” for assisting Dr. Teresa Ramirez (Sol Rodriguez) as she defends her Las Mariposas medical clinic from an ICE raid, finds himself inside a detention facility with Teresa, where Rios is tased for speaking against an officer’s (Leif Gantvoort’s) racist treatment of a fellow detainee named Pedro (Oscar Camacho). Rios and Teresa eventually get the opportunity to converse before Teresa’s released from custody, with Santiago Cabrera and Sol Rodriguez sharing an easy, natural romantic tension in these scenes.

Rios then boards an ICE bus that will transport him to a Sanctuary District on the border, forcing Raffi and Seven to act precipitously to free him. Raffi’s frustrations in dealing with law enforcement’s bureaucracy as “Watcher” unfolds are delightful to watch, with Michelle Hurd communicating Raffi’s disgust in the face of institutional indifference so well that it pushes Seven, always the calming force in their relationship, to steal a Los Angeles Police Department vehicle to pursue Rios’s bus. The resulting chase scene through L.A.’s streets is a tribute to the creativity of Lea Thompson and Picard’s stunt team, who, alongside Hurd and Ryan’s talent for sniping at one another, make this action sequence fresh, exciting, and funny.

Raffi and Seven must enlist Jurati’s aid to find Rios, which forces Agnes to request the Borg Queen’s assistance in activating La Sirena’s transporters. Doing so gives the Queen an opportunity to try manipulating Jurati’s emotions by playing upon her perceived inadequacies and regrets, with Annie Wersching becoming coolly seductive as their conversation develops. Jurati doesn’t fall for this ploy, but the slight hesitations and downcast eyes that Alison Pill brings to this interaction suggests that, although Agnes is smart enough to understand precisely what the Queen is attempting, the Queen’s words hold just enough truth and foster just enough doubt to endanger Jurati’s psychological equilibrium.

Jurati’s presence also helps solve a longstanding mystery about Picard’s lineage. “Watcher’s” teaser finds Picard and Jurati exploring Château Picard’s abandoned 21st-Century estate, with Picard telling the curious Jurati that his ancestors hid in tunnels underneath the château when, during World War II, the Nazis occupied France and commandeered the house as a base of operations. His family fled to England despite never surrendering their claim to the estate, which provides a clever explanation for why the French Picard speaks in an English baritone, one of the quirks of Patrick Stewart’s casting that TNG rarely acknowledged. It’s this sort of small detail that, when combined with this episode’s sociopolitical commentary, creates a richly consistent, yet fantastic world that Star Trek: Picard’s second season nicely advances (and that “Watcher” exemplifies).

When Picard, with Young Guinan’s help, finally encounters this entry’s titular character, he’s shocked to see a human woman who resembles Laris (Orla Brady), his winery’s Romulan caretaker. This watcher, described by Young Guinan as a “Supervisor” belonging to a group of operatives “peppered through the galaxy, assigned to protect the destiny of certain individuals,” not only recalls the characters called Primaries in 12 Monkeys but also stirs dim memories of the character Gary Seven, the mysterious Supervisor encountered by James T. Kirk (William Shatner) and the crew of the U.S.S. Enterprise (NCC-1701) in The Original Series’s second-season finale, “Assignment: Earth” (an episode that Gene Roddenberry intended to serve as the backdoor pilot for a spinoff series that NBC never ordered).

This eerie sequence sees the Watcher temporarily possessing the bodies of several people in the public park to which Young Guinan brings Picard to meet his quarry. This possession causes each person’s eyes to white out, with the young girl (Isabella Meneses) who first intercepts Picard being quite a sight to behold, even if the Watcher seems unconcerned about the implications of temporarily overriding a child’s mind. Equally eye-popping is the square portal that the Watcher opens to take Picard to an unknown destination, whose visual effect evokes Gary Seven’s transporter in “Assignment: Earth.” Ending on this image promises that Picard Season 2 will continue enthusiastically mining the Trek franchise for allusions, Easter eggs, and references in future episodes.

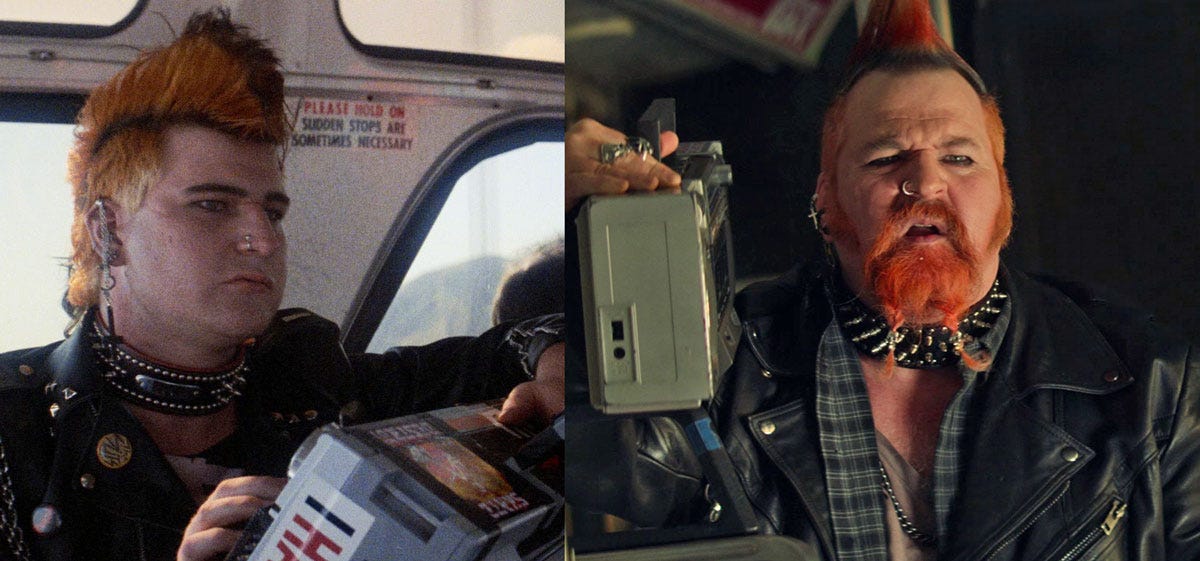

One allusion deserves brief comment. As “Watcher” begins, Raffi and Seven ride a Los Angeles bus on which a man sporting a pink mohawk blasts, from his old-style boombox, a song titled “I Still Hate You.” When Seven asks this fellow to stop this noise, he complies and apologizes, leading longtime fans to chuckle at yet another reference to 1986’s Star Trek IV: The Voyage Home, the feature film where Kirk and Spock (Leonard Nimoy) encounter this same man loudly playing the song “I Hate You” on a San Francisco bus, leading Spock to nerve pinch him after he profanely refuses to switch it off.

This character, identified only as “Mohawk Punk” in the closing credits, is once again played by Kirk R. Thatcher, the man who played The Voyage Home’s bus punk, who worked as an associate producer on that movie, and who wrote both “I Hate You” and “I Still Hate You” for the Trek franchise. Does the presence of Mohawk Man, who moved to Los Angeles sometime in the intervening 36 years, disrupt the timeline? Should this character behave as if faintly recalling his earlier confrontation with Kirk and Spock if time has changed so irrevocably that the Federation never existed and, consequently, neither man travelled back to 1986 San Francisco in the first place? Does Matalas wish to indulge Trek nostalgia so fulsomely that creating this moment of pure fan service breaches “Watcher’s” internal consistency and, per J.R.R. Tolkien, collapses this installment’s believability?

Yes, no, and maybe.

Still, I’m glad to see Thatcher again. And I’m happy to know that Matalas, along with Star Trek: Picard’s cast and crew, maintain a sense of humor about their work.

Indeed, I’m pleased they can gently mock the absurdities of the story they’re telling while taking this tale seriously enough to have some fun with it. This statement may seem a paradox, but it’s a paradox that I enjoy and approve and encourage. “Watcher” is sober and silly, profound and frothy, somber and bright all in one go—in short, a charming mélange of tonal shifts that keeps us guessing.

So, bravo to everyone involved and, if it’s not too much trouble, keep ‘em coming.

NOTES

J.R.R. Tolkien, “On Fairy Stories,” University of Houston ILAS 2350 course page, https://uh.edu/fdis/_taylor-dev/readings/tolkien.html.

Tolkien’s essay began life as a public address titled “Fairy Stories” that he gave as the Andrew Lang Lecture at the University of St. Andrews, in Fife, Scotland, on 8 March 1939. It first appeared in essay form in the 1947 festschrift volume Essays Presented to Charles Williams, edited by C.S. Lewis, who was Tolkien’s close friend, fellow member of the Oxford University literary group The Inklings, and best known as the author of The Chronicles of Narnia book series.

A .pdf copy of Tolkien’s essay is available at https://coolcalvary.files.wordpress.com/2018/10/on-fairy-stories1.pdf.

Ibid.

Ibid.

Ibid.

Ursula K. Le Guin, “My Appointment with the Enterprise: An Appreciation,” TV Guide, 14 May 1994, https://angelfishing.tumblr.com/post/153483709178/ursula-le-guin-on-star-trek-tng.

Le Guin, addressing TNG’s conventionally feminine roles, writes, “Many of us wish that Tasha Yar (Denise Crosby) and Ens. Ro (Michelle Forbes) had stayed on board to shake things up, but at least we got Whoopi Goldberg wearing those great hats.”