Whispers in the Dark

“Can You Hear Me?" gives voice to unspoken terrors and unexpected kindnesses.

Note to The Vestibule’s subscribers: My review of “Praxeus” (Doctor Who Series 12’s sixth episode) did not find its way to your email inboxes last Thursday (17 February 2022). I’m not certain why, but you may find “Doctor(ing) Disaster” here. As always, please read, enjoy, and leave a comment. All the best, Jason

Doctor Who

“Can You Hear Me?”

Series 12, Episode 7

Written by Charlene James and Chris Chibnall

Directed by Emma Sullivan

Starring Jodie Whittaker, Tosin Cole, Mandip Gill, and Bradley Walsh

Guest Starring Clare-Hope Ashitey, Ian Gelder, Aruhan Galieva, Nasreen Hussain, Michael Keane, Bhavnisha Parmar, Anthony Taylor, Buom Tihngang, Everal A. Walsh, and Sharon D. Clarke

49 minutes

Original broadcast 9 February 2020

1. Fears & Cheers

When Doctor Who fans claim that certain moments, scenes, sequences, and episodes send them diving behind their couches, “Can You Hear Me?” is the type of story they have in mind. The notion of hiding behind sofas when Who comes on the screen has become so pervasive, especially among the franchise’s British fans, that it now qualifies as a cliché that committed audience members spout no matter how true it may (or may not) be.

New Who showrunners Russell T. Davies, Steven Moffat, and Chris Chibnall have all stated that, as youngsters, Classic Who’s panoply of antagonists, villains, and monsters—the Cybermen, the Daleks, the Master, the Silurians, the Zygons, and even the Sontarans—frightened them during that program’s 1963-1989 run, with Moffat once claiming that hearing Ron Grainer’s & Delia Derbyshire’s indelible theme music was enough to raise his hackles and his blood pressure.

So many participants in New Who’s (2005-Present) cast and crew have joked about how the old or new program sent/sends them scuttling behind their furniture, sometimes while they’re reading an episode’s script—as Doctor Who Magazine reporter Benjamin Cook confesses during his email correspondence with Davies (as documented in their terrific book, The Writer’s Tale: The Final Chapter) about Davies’s Series 4 masterpiece “Midnight” (and as Davies admits about reading Moffat’s first Series 5 teleplay for “The Eleventh Hour”)1—that the idea of Doctor Who, at best and at base, being scary fun for the whole family shall never disappear from popular conceptions about this franchise.

In truth, these comments are so regularly voiced in Blu-ray and DVD audio commentaries, behind-the-scenes documentaries, press interviews, and the various companion series devoted to the New Who franchise’s production (Doctor Who Confidential, Doctor Who Extra, Doctor Who: The Fan Show, and Torchwood Declassified) that they have become running jokes amongst longtime fans, who now expect to hear such declarations from the people who make Who for our viewing pleasure. Doctor Who may be family entertainment, but that designation doesn’t mean it must always be lighthearted fun or happy frolics through the time vortex (despite its generally optimistic outlook on life, the universe, and everything after).

Both Classic and New Who tout their menageries of strange creatures, otherworldly beings, and eerie monsters as reasons to watch, while the British Broadcasting Corporation (BBC) uses these extraterrestrial troublemakers, humanoid opponents, and paranormal visitors—androids; ghosts; Autons; Cybermen; Daleks; Ice Warriors; Judoon; living-rock monsters; Ood; Sea Devils; sentient stars, moons, and planets; Silurians; Sontarans; vampires; Vashta Narada; werewolves; Weeping Angels; Zygons; indeed a cosmic bestiary so vast that entire websites are devoted to tracking its ever-expanding membership—as selling points for tuning into Who (or, these days, streaming it), buying its ancillary merchandise, and keeping the franchise alive.

“Can You Hear Me?” adds its own creatures to Who’s villainous ranks in the form of the Chagaska, clawed and snarling beasts that haunt a fourteenth-century Syrian hospital (in 1380 Aleppo, to be precise) before attacking its workers, only one of whom, Tahira (Aruhun Galieva), takes the Chagaska as serious threats to the hospital’s safety (by simply believing in their existence). Yet Tahira’s insistence that the Chagaska are real becomes the linchpin of an installment that depicts two gods of chaos creating fear across time and space, but that, in an unexpected turn, contemplates with welcome compassion how caring for one’s mental health is as important as tending to one’s physical condition.

2. Hearth Stones & Home Fires

“Can You Hear Me?” finds the Thirteenth Doctor (Jodie Whittaker) dropping her three companions—Ryan Sinclair (Tosin Cole), Yasmin “Yaz” Khan (Mandip Gill), and Graham O’Brien (Bradley Walsh)—in their hometown of Sheffield, England so they may spend time with family and friends. Series 12’s premiere episode, “Spyfall: Part One,” begins the same way, which permits co-writers Charlene James and showrunner Chris Chibnall, in this seventh outing, to depict Ryan, Yaz, and Graham as individuals whose lives don’t fully circle around their TARDIS voyages. A pleasant dramatic corollary to this narrative development is seeing how travelling with the Doctor affects each companion’s domestic circumstances.

Attending to the quotidian realities of Sheffield’s hometown heroes further establishes New Who’s concern for the lives of its everyday characters. The Who franchise has always done so, but Russell T. Davies emphasized this working-class ethos during Series 1-4 by focusing upon the family backgrounds and dynamics of companions Rose Tyler (Billie Piper), Martha Jones (Freema Agyman), and Donna Noble (Catherine Tate).

Their parents, grandparents, and siblings all became important subsidiary characters, which may be Davies’s most significant shift in Doctor Who’s focus. Whereas Classic Who’s companions functioned as assistants whose earthbound lives were secondary (or absent) during that show’s 1963-1989 run, Davies created Rose Tyler to become New Who’s viewpoint character, establishing the Doctor’s companion as an audience surrogate whose perspective is just as important—if not more significant—than the Doctor’s outlook.

Steven Moffat continued this new Davies tradition in Series 5-10, although more fitfully, and, given Moffat’s compulsion to revolve his female companions’ lives around the Doctor’s existence, less successfully overall. Amy Pond (Karen Gillan), Clara Oswald (Jenna Coleman), and River Song (Alex Kingston) all start their New Who lives as women so devoted to the Eleventh Doctor (Matt Smith) that his centrality becomes uncomfortable in its sexist implications.

Clara, for example (and despite being a grown woman), is called the Doctor’s “Impossible Girl” throughout Series 7 (her first), which culminates in Clara, during that season’s finale (“The Name of the Doctor”), scattering herself throughout his timeline to ensure that the Doctor isn’t erased from history. Growing fan backlash prompted Moffat to deepen Clara’s character once Peter Capaldi’s Twelfth Doctor arrived in Series 8’s inaugural installment, “Deep Breath.”

Some fans find Pearl Mackie’s delightful Bill Potts to be Moffat’s best-realized female companion although she only appears in Series 10 (and despite audiences learning less about her personal background than Amy, Clara, or River, which is perhaps inevitable given Bill’s 14 onscreen appearances versus Amy’s 35, Clara’s 40, and River’s 17 appearances), but, no matter how many outings or seasons a companion accompanies the Doctor, developing each one into an autonomous personality (rather than a mere sounding board) is key to the character’s success.

Chris Chibnall’s decision to include three companions in Series 11 caused some fans to complain, wrongly I think, about overloading the program with too many co-leads, meaning that Ryan, Yaz, and Graham don’t emerge as well-rounded people, with Yaz taking the brunt of Chibnall’s authorial inadequacies. Series 11, in fact, does Yaz a disservice until its sixth episode, “Demons of the Punjab,” focuses upon her family life.

That season, during its first five installments, relies upon Mandip Gill’s terrific performance to obscure Yaz’s thin characterization, but later episodes balance all three companions’ screen time better than Series 11’s early adventures. Even so, seeing Ryan’s, Yaz’s, and Graham’s lives away from the TARDIS in “Can You Hear Me?” is an opportune development dovetailing with the Chagaska storyline better than one might imagine.

3. Gods & Monsters

Yet the Chagaska aren’t this episode’s sole, or primary, threat. Tahira is only one person bedeviled by the nighttime appearances of a bald man sporting impressive head tattoos whom we eventually learn is named Zellin (Ian Gelder) and who eventually reveals he is not a man at all, but a powerful being with godlike powers.

Zellin haunts the dreams of several people in 2020 Sheffield, including Ryan’s best mate, Tibo (Buom Tihngang), who first appeared in the early minutes of “Spyfall: Part One.” Now, however, Tibo’s life has taken a downward turn, as Ryan discovers when he learns that his friend has become a jumpy—even paranoid—person, as the many locks bolted to Tibo’s front door attest. Tibo confesses he’s been having terrible dreams involving Zellin, but refuses to seek professional help about this issue before asking Ryan to stay the night as reassurance.

Ryan agrees, then is startled to see Zellin standing in Tibo’s flat later that evening. We viewers are even more surprised when all five fingers of Zellin’s left hand detach themselves, then shoot toward Tibo—with Zellin’s index finger lodging itself into Tibo’s ear—in images so weird that we don’t quite know what to make of them. Graham, meanwhile, plays cards with two of his best friends, Gabriel (Everal A. Walsh)—an old work colleague first seen in Series 11’s “The Woman Who Fell to Earth” (the Chibnall era’s premiere, no less)—and the bespectacled Fred (Michael Keane).

This scene is nicely staged by first-time New Who director Emma Sullivan and beautifully played by all three actors. Their easy camaraderie, to say nothing of Gabriel’s and Fred’s gentle concern for Graham’s health and for his recovery from the death of his wife (Grace Sinclair-O’Brien), transforms what might seem a throwaway scene into a quiet evocation of how important such relationships are.

While dealing cards, Graham receives psychic projections from a woman who communicates with him from far across the cosmos, who’s trapped in a terrible cage or prison, and who’s named Rakaya (Clare-Hope Ashitey). These images are blurry, brief, and incomplete, but Graham finds them troubling enough to ask the Doctor to release Rakaya from captivity.

Yaz, meanwhile, grudgingly marks an unspecified anniversary with her sister, Sonya Khan (Bhavnisha Parmar), at their parents’ flat, falling asleep on the couch and dreaming of standing on an empty road somewhere in the English countryside, where, in an ominous sight, Yaz sees both Sonya and a silent police officer staring at her. This vision startles her awake, where she finds Zellin standing over her. When he dissolves into black dust, viewers begin to realize that Zellin and Rakaya are the common threads connecting each character’s fears and nightmares.

The Doctor, with Tahira in tow, takes her companions and Tibo on a TARDIS trip to recover Rakaya, only to land on a far-future space station that’s situated near two planets falling into one another. This observation platform not only monitors these planets’ collision but also surveils a “geo orb” stuck between them.

And, dear reader, if you guessed that this orb is, in fact, Rakaya’s prison, give yourself full marks. The Doctor unsurprisingly discovers how to release Rakaya, only to realize too late that Zellin has concocted this entire scenario—and every disturbing vision and nightmare that Ryan, Yaz, Graham, Tibo, and Tahira have experienced—to dupe the Doctor into freeing Rakaya, his partner goddess and, as he says, the more powerful of the two.

Zellin and Rakaya, you see, are immortals who revel in cruelty. They take pleasure in toying with the lives of “lesser beings” (otherwise known as regular people). Zellin and Rakaya feed on fear, with Zellin creating nightmares across time and space that nourish his captive partner. Once freed, Rakaya vows to drain every person on Earth of their inner fears, doubts, and anxieties, which she promises to release leisurely so that she may feast upon the resulting terror. That this process will kill all humanity concerns neither she nor Zellin in any way.

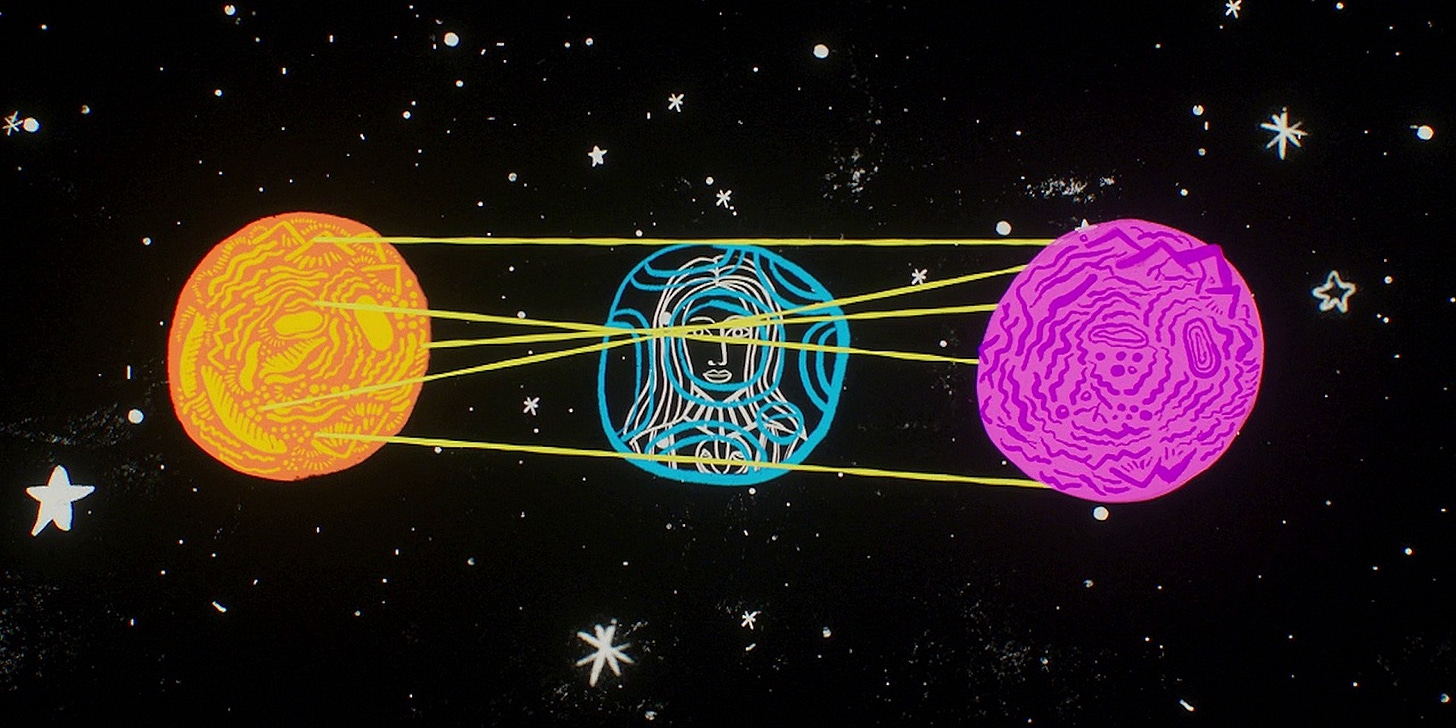

Perhaps the most burning question posed by this storyline is: How did Rakaya come to be captured in the first place? James and Chibnall tell this tale in a brief, animated flashback sequence narrated by Rakaya. She and Zellin enjoyed tormenting the inhabitants of both planets, setting them against one another for their—meaning, Rakaya and Zellin’s—amusement (shades of Greek drama and the Biblical story of Job here), until both worlds’ populaces unified, set their planets on a collision course, and trapped Rakaya between them—inside the geo orb—to serve as a buffer that ensures Rakaya’s endless confinement, ceaseless boredom, and eventual insanity.

This flashback, in both its language and animation style, recalls the inventive prologue of Martin Rosen’s 1978 cinematic adaptation of Richard Adams’s 1972 novel Watership Down, in which the rabbit god Frith (voiced by Sir Michael Hordern) narrates the creation myth of all rabbits on Earth.

This vignette also marks the first animated bit of New Who since Series 2’s “Fear Her.” It cleverly disguises exposition necessary to understanding the plot of “Can You Hear Me?” in suppler fashion than Rakaya’s monologue alone would, saves money on expensive visual effects, and—in its most noticeable parallel to Rosen’s Watership Down—stresses the fable-like resonances of Rakaya and Zellin’s backstory.

“Can You Hear Me?,” as this summary makes clear, combines standard science-fiction-and-fantasy (SFF) elements to offer a veritable stew of generic tropes. Whether inspired by ancient Greek drama, the writing of H.P. Lovecraft, the work of Robert Bloch, or all three, the notion of gods who entertain themselves at the expense of insignificant mortals has a history stretching back thousands of years, just as the concept of beings capable of ingesting fear itself features in so many SFF works that these conventions are well-known (and well-worn).

Yet “Can You Hear Me?” refreshes them into a grimly fascinating story about how, when gods become monsters, good people must rely upon their individual and collective strengths to survive the ensuing whirlwind.

4. Pasts & Presents

New Who has told similar stories before, with Series 2’s aforementioned “Fear Her” and Series 6’s “Night Terrors” being exemplary instances of this subgenre. Even if neither episode is beloved by the wider Who audience, each is an underrated gem, with “Fear Her” being much better than its 5.8 (out of 10) Internet Movie Database (IMDb) rating implies.

Both installments distill the internal-fears-becoming-external-reality plotline down to its fundamental components in the same way that the Star Trek franchise’s fascination with this story form does (see The Next Generation’s Season 1 episode “Where No One Has Gone Before” and Season 4’s “Night Terrors,” Deep Space Nine’s Season 1 installment “If Wishes Were Horses” and Season 3’s “Distant Voices,” Voyager’s Season 2 triumph “The Thaw,” and Enterprise’s Season 2 outing “Vanishing Point” for variations on this theme).

More significant is how “Can You Hear Me?,” by bridging continuity backward to Series 11 and forward to Series 13, functions as the Chibnall era’s narrative fulcrum. Chibnall first advances the concept of a powerful, man-and-woman couple in Series 11’s finale, “The Battle of Ranskoor Av Kolos,” by creating the Ux, a “duo-species” in which only two members—one female, one male—exist at any time. The two Ux encountered during this episode, Andinio (Phyllis Logan) and Delph (Percelle Ascott), possess immense powers of telepathy that allow them to dimensionally engineer whole environments by concentrating their minds on this task.

Series 13, subtitled Flux, sees another ancient and powerful couple—this time, sister-and-brother duo Azure (Rochenda Sandall) and Swarm (Sam Spruell)—hound the Thirteenth Doctor so relentlessly that this entire, six-episode serial hinges on Azure and Swarm’s revenge quest against Thirteen, who, while working as a Division agent during her earlier incarnation as the Fugitive Doctor (Jo Martin), imprisoned Azure and Swarm for attempting to destroy creation itself.

Azure and Swarm, moreover, occupy a Division space station that observes the Flux shockwave annihilating the universe, so, when Rakaya and Zellin take command of the monitoring platform that previously imprisoned her, we recognize Chibnall rehearsing in “Can You Hear Me?” Flux’s basic premise, antagonists, and plot points.

These connections aren’t necessary for casual viewers to enjoy “Can You Hear Me?,” but they demonstrate that Chibnall planned his three seasons as New Who’s showrunner more carefully than his harshest detractors claim. “Can You Hear Me?,” however, is also a pleasing standalone installment featuring fine performances from every cast member, with guest actors Buom Tinhgang, Clare-Hope Ashitey, and Ian Gelder leading the pack.

Gelder is no newcomer to the Who franchise, having played the role of Mr. Dekker in Torchwood’s terrific third series (2011’s Children of Earth) and having provided the voice of the extraterrestrial Remnants in the Chibnall era’s second outing, 2018’s “The Ghost Monument.” Ashitey may be most famous for playing the role of Kee, the mother of future humanity, in Alfonso Cuarón’s 2006 cinematic adaptation of P.D. James’s 1992 novel Children of Men, but her television work in Suspects (2014-2016), Shots Fired (2017), Seven Seconds (2018), and the third season of Neil Jordan’s Riviera (2017-2020) proves Ashitey to be one of Britain’s great working actors.

Ashitey and Gelder share a spooky, otherworldly chemistry that makes their characters’ disregard for human life chilling, while Emma Sullivan shoots their scenes on the streets of Sheffield—after they leave Team TARDIS on the space station to perish in the planetary collision—with long lenses, canted angles, and harsh lighting that not only deliberately mismatches foreground and background images but also creates a sense of unreality that implies, without confirming, that Rakaya and Zellin are Eternals, transcendental beings introduced to Who lore in the 1983 Fifth Doctor (Peter Davison) serial Enlightenment.

5. Listening Tours & Talking Cures

Good as its actors are, “Can You Hear Me?” excels in its dramatic evocation of the inner doubts, fears, and anxieties that confound all human beings (or what Zellin calls “built-in pain”). Rakaya and Zellin may prey upon what they see as weaknesses in the human psyche, but the Doctor sees these psychological phenomena as strengths that create the admirable resilience that gets her human friends through each day.

They also help clear space for this entry’s lovely, final ten minutes, in which Tibo attends a therapy session where he admits—for the first time—the difficulties caused by his inability to connect with other people (in the ways he thinks he should), while Yaz, in a revelation that explains many behavioral tics that she’s manifested throughout her previous appearances (and, as a bonus, her choice to join Sheffield’s police force), remembers the day, three years prior, when she ran away from home to escape pronounced school bullying.

The anniversary that Sonya commemorates involves Yaz being intercepted by Sheffield police officer Anita Patel (Nasreen Hussain), whom Sonya—worried about her older sister’s well-being—calls for help. Anita offers Yaz encouragement, assistance, and the following deal: If Yaz returns home but her situation doesn’t brighten in three years’ time, Anita will give Yaz fifty pounds. If Yaz improves, she will owe Anita fifty pence. These scenes (two flashbacks and their bookending coda, which sees Yaz, in the present day, knocking on Anita’s front door and handing her fifty pence) are not only affecting in their emotional strength but also testaments to Emma Sullivan’s, Mandip Gill’s, and Nasreen Hussain’s talents.

Tibo discovers how powerful a force kindness can be when, during his group-therapy session (with three other men), a character named Andrew (Anthony Taylor) smiles and says the words “It’s not just you” so gently that Tibo understands he’ll finally receive the help he needs. Taylor’s terrific, even beautiful, delivery of this single line qualifies as one of this episode’s best performances (even though Taylor is onscreen for only twenty seconds).

Although no character ever mentions the word (or condition) depression, “Can You Hear Me?” unambiguously endorses the importance of mental-health treatment. While it may seem jarring to hear Tahira, a 14th-Century woman, say, “You tell me creating happiness is important to my mental well-being” in this episode’s opening scene, her dialogue at least introduces a theme that runs throughout “Can You Hear Me?” (even if it employs language more appropriate to 21st-Century conversations about mindfulness, to say nothing of the concepts of “therapy culture,” “therapy-speak,” and “trauma-talk” that Frank Furedi examines in his 2003 book Therapy Culture: Cultivating Vulnerability in an Uncertain Age and that commentators as diverse as Pauline Johnson, Will Self, and Katy Waldman discuss in their work).2

The Doctor affirms this theme’s importance when she recognizes the Persian word bimaristan outside Tahira’s hospital. As the Doctor notes in a teachable moment, “Islamic physicians were known for the enlightened way they treated people with mental-health problems.” If this observation seems too “on the nose” for its setting and its audience, interested viewers should take heart that “Can You Hear Me?” gains subtlety as it continues.

Graham’s experience, coming midway through “Can You Hear Me?,” is among the most harrowing. While trapped by Zellin on the space station, Graham dreams that he’s in a Sheffield hospital receiving renewed treatment for his cancer, whose remission has ended. Even worse, Graham’s nurse is Grace Sinclair (Sharon D. Clarke), whose cold and remote bedside manner stands in unsettling contrast to the warmth and humor of her Series 11 appearances. As always, Clarke is excellent in this short scene, which underscores the terrible cost of Rakaya’s and Zellin’s depravity more than just about anything else in this entry.

When Graham later confides concerns about his health to the Doctor, she takes a long pause before replying, “I should say a reassuring thing now, shouldn’t I?” Some fans have objected to this reaction as a tin-eared response, but the way Jodie Whittaker and Bradley Walsh play this scene, particularly Graham’s amused reaction when the Doctor adds, “I’m just going to subtly walk towards the console and look at something. And then, in a minute, I’ll think of something I should’ve said that might’ve been helpful” (while doing exactly that), shows that she understands Graham’s genial temperament well enough that, no matter how socially awkward she may be when faced with such intimate confessions (an awkwardness manifested by every one of her predecessors going back at least as far as Christopher Eccleston’s Ninth Doctor), Thirteen offers Graham reassurance not by ignoring—or making light of—his doubts, but by acknowledging them as legitimate fears that she can’t fully alleviate no matter what she says or does.

As such, these final scenes (including a brief conversation between Ryan and Yaz about how travelling with the Doctor forces them to miss their friends’ and families’ lives) continue Series 12’s mature handling of difficult topics. “Can You Hear Me?,” indeed, is among this season’s best outings. Not everyone agrees, of course, but “Can You Hear Me?” is worth a second look, and a third, and even a fourth. This recommendation, like the episode itself, invites viewers to watch, to appreciate, and to enjoy this installment’s inventive fusion of SFF tropes with moments that could only appear on Doctor Who.

So, my friends, if you accept this summons in the same optimistic spirit that it’s offered, I predict you’ll be glad that you did.

FILE

NOTES

See Davies and Cook’s The Writer’s Tale: The Final Chapter (BBC Books, 2010)—specifically Cook’s entry dated “Thursday 18 October 2007 13:43:38 GMT” (in Chapter Eight)—for his comments about how reading Davies’s “Midnight” script is an impressive and frightening experience. See Davies’s entries dated “Tuesday 12 August 2008 00:46:00 GMT” through “Tuesday 12 August 2008 01:03:10 GMT” (in Chapter Sixteen) for similar comments about Moffat’s “The Eleventh Hour” teleplay.

Furedi’s Therapy Culture (Routledge, 2003), in the two decades since its release, has become an oft-invoked text about the benefits and liabilities that the widening exposure of professional therapists’ language, methodologies, and practices means for American, Canadian, and British societies, although Furedi’s controversial political opinions—particularly his attacks on the realities of global warming and human-induced climate change, as well as what Benjamin Doxtdator terms the “colorblind racism” of Spiked (an online magazine descended from Living Marxism, the official journal of Britain’s Revolutionary Communist Party, both of which Furedi helped found)—make Therapy Culture a highly contested volume about its subject.

Pauline Johnson’s essay appears as the eighth chapter of the 2010 scholarly anthology Modern Privacy: Shifting Boundaries, New Forms (see pages 117-132), which she co-edited with Harry Blatterer and and Maria R. Markus. Will Self’s and Katy Waldman’s pieces are recent magazine essays (or “think pieces”) that plumb cultural concerns about therapeutic language’s influence upon American and British literature, cinema, and television.