Master Builder

Retro Book Review (#0.5) of Robert C. Cumbow's Order in the Universe: The Films of John Carpenter

Note to The Vestibule’s subscribers: When I inaugurated this newsletter’s Retro Book Review series by reprinting my appraisal of Stuart Banner’s excellent 2005 monograph How the Indians Lost Their Land: Law and Power on the Frontier, I claimed this retrospective would include every book review that I’ve published while working as an English professor (i.e., a professional scholar) at the University of Guam.

Don’t you believe it.

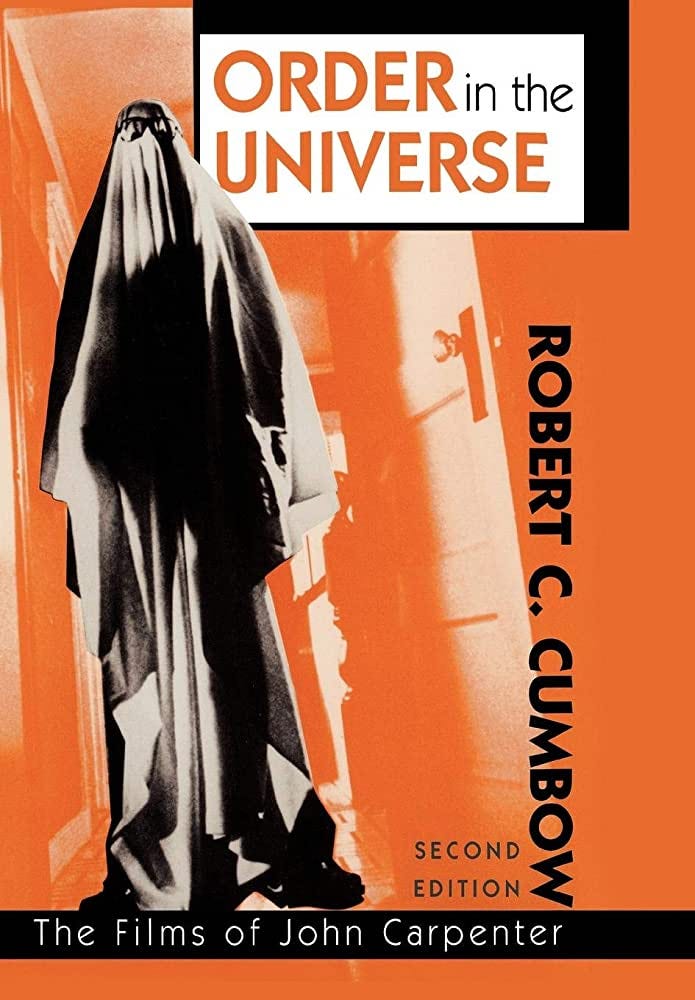

With this second entry, I go back on my word—and go back in time—by reprinting my first-ever professional book review (yes, really!) of Robert C. Cumbow’s 2000 monograph Order in the Universe: The Films of John Carpenter (Second Edition). This short assessment first appeared in a 2002 issue of Film & History: An Interdisciplinary Journal of Film and Television Studies (Volume 32.1, to be precise).

Please, dear reader, allow me to explain.

I could cite “best intentions” (without mentioning “the road to Hell”) to clarify why I’ve taken a half-step back to my days as a graduate student (August 1998 to December 2004) at Washington University in St. Louis’s Department of English & American Literature (as it was then known, having changed its name to the Department of English sometime in the 2010s). As always, the truth is the best—and easiest-to-remember—explanation, to cite an aphorism my mother was fond of repeating.

A few weeks ago, while preparing to address a cohort of new graduate students in UOG’s Master of Arts in English Program at the behest of their professor, my colleague, and my friend Dr. Hyun-Jong Hahm, I found Film & History 32.1 nestled in the corner of one of my campus-office bookcases. Dr. Hahm asked me to bring as many personal publications as possible, especially if they’d appeared in print during my grad-school years, to prove to her students that the life of a working scholar involves writing, writing, and more writing, making it good practice for MA students to begin publishing their own work while still taking classes.

Academic reviewing is a time-honored method of getting one’s name and opinions into print, to say nothing of the professional connections that accrue from evaluating books for different journals, so I was happy to oblige Hyun-Jong’s request. While hunting through my bookcases, I pulled Film & History 32.1 off the shelf for the first time in 10 (or more) years.

My association with this journal began in April 2000, when Editor-in-Chief Peter C. Rollins accepted my paper proposal about Aaron Sorkin’s NBC White House drama The West Wing (1999-2006) for a panel titled “Images of American Presidents in Film and Television” that Peter was organizing for that year’s Film & History conference (one of the American Historical Association’s many annual meetings), to be held in Los Angeles, California from 9-12 November 2000. Those dates coincided with the 7 November 2000 presidential election, making Peter’s panel both timely and apposite.

Peter, his co-organizers, and everyone who agreed to participate in this panel thought that, by the time we reached the West Coast, we’d know whether Al Gore or George W. Bush would be inaugurated the United States’s 43rd president come 20 January 2001. Yet as we arrived in L.A. to enjoy California’s pleasant November weather and several convivial chats about the political madness enveloping us, the events that’d begun on Election Night (and that wouldn’t be resolved for 36 bitter days—perhaps the longest pre-pandemic month of the past quarter century—when Florida recounts, Brooks Brothers riots, Supreme Court lunacies, and hanging chads became part of our national lexicon) confounded our expectations, as well as our remaining innocence, about presidential politics (and, in truth, about American history writ large).

This drama, as improbable as anything Sorkin could’ve dreamed up for his smash-hit television series (then just entering its second season), provided hours of fascinating conversations, hilarious commentaries, and dire predictions about what might prevail if the worst happened (i.e., if Bush made his way into the Oval Office, which, if memory serves, all my fellow panelists except Peter thought would be disastrous).

Still, our panel was a tremendous success, with my paper (titled “From The American President to The West Wing: A Scriptwriter’s Perspective”) being well received by the audience, whose members posed many smart questions that I hope I answered with grace and wit. During those four days, we enjoyed good food and many drinks at local bars and restaurants, often presided over by Peter, who acted as our gentle host, our genial emcee, and our surrogate father.

Peter even set up a special visit to the Ronald Reagan Presidential Library & Museum that allowed us to tour the entire facility, including its normally closed-off archive rooms (where staff members catalogued the millions of pages and countless hours of video amassed during Reagan’s eight years in the White House), plus the man’s private office, which most visitors never saw because it wasn’t part of the museum’s standard tour. Despite my personal disdain for Reagan’s presidency and Reagan himself, I remained impeccably polite during this journey (really, dear reader, I was! I was! Ya gotta believe me!) even if the urge to crack jokes about “Ronnie the dunderhead” and “Nancy the ‘Just Say No’body” poked and prodded me throughout that day.

Peter and I became friendly during these events, leading him to invite me to submit my essay for an academic anthology he was putting together for Syracuse University Press. Peter and his co-editor, John E. O’Connor, went through my manuscript with a fine-toothed comb, provided equally incisive comments about my second draft, and eventually included it as the eighth chapter of The West Wing: The American Presidency as Television Drama, marking my official entry into the world of professional, published scholarship. And all while still a graduate student!

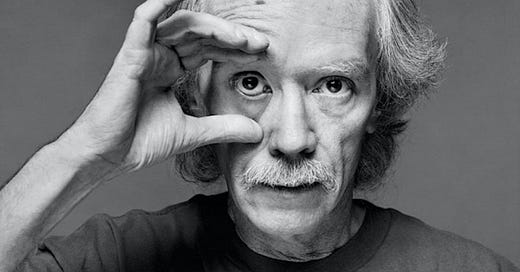

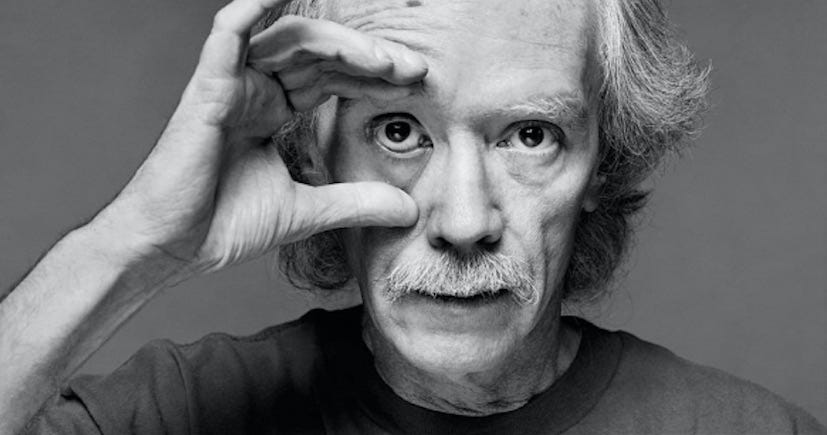

Peter’s generosity didn’t stop there. He asked me to become an associate book-review editor for Film & History, a post I eagerly accepted. Peter, remembering a fun and lively conversation we’d shared at the conference hotel’s bar in November 2000 (where, despite our political differences, we “geeked out” while discussing our mutual enthusiasm for John Carpenter’s movies), personally asked me to evaluate Robert Cumbow’s Order in the Universe when, sometime in late summer 2001 (seven or eight months after its release), he (Peter) pulled its second edition from the never-ending pile of books sent to Film & History’s office by academic publishers.

The resulting review, printed in Film & History 32.1 with the uninspiring title “Worthy Addition,” marked another milestone in my scholarly career. While not the first book review I’d written, it was the first review to make it into print. I’m pleased Peter gave me the chance to read Cumbow’s fine book, but unsatisfied by the review itself. Wooden, leaden, and all the other “-en” adjectives we use to describe pedestrian prose (when said prose isn’t unbearably awkward), revisiting this early piece hasn’t been an entirely happy experience for me, but, dear reader, please judge for yourself. The original version resides in the “Files” section below.

Unlike Samuel Taylor Coleridge and George Lucas, I’ve so far resisted the temptation to revise—to the point of obsession, if not madness—my older work, especially pieces from my existing publications now posted to The Vestibule, because I don’t enjoy reading my own writing no mater how much I enjoy writing it. And I generally enjoy writing it just fine even if encountering it again irks me because I can only see the flaws, the seams, and the missed opportunities.

Yet I can’t leave this review—my earliest and, perhaps, my worst (how’s that for an endorsement?)—untouched. I submitted its manuscript with the name “Master Builder: Robert C. Cumbow Unpacks John Carpenter’s Enduring Appeal,” which remains my preferred title. My changes are meant to improve rhythm, syntax, and diction, so, dear friends, I hope they accomplish this task rather than treading water, marking time, going nowhere fast, or whatever other metaphor you prefer.

One final note: Peter C. Rollins passed away on 23 March 2015 at the age of 72. He was a generous mentor, a lovely man, and a good friend. I still miss him.

May he rest in perfect peace.

Order in the Universe: The Films of John Carpenter

Written by Robert C. Cumbow

Published by Scarecrow Press

Second Edition, 2000

295 pages

ISBN 0-8108-3719-6

$35.00

1. Sacred & Profane

Robert C. Cumbow, in the second edition of his excellent monograph Order in the Universe: The Films of John Carpenter (first published 23 years ago), provides many treasures for lovers of accessibly written film criticism. Cumbow approaches Carpenter’s oeuvre (excepting 2001’s then-unreleased Ghosts of Mars plus, it goes without saying, every later movie and television episode directed by Carpenter) from an intellectual, if not purely scholarly, standpoint that explores, in laudable detail, the images, themes, symbols, and narrative concerns that fascinated Carpenter during his first three decades as a feature filmmaker.

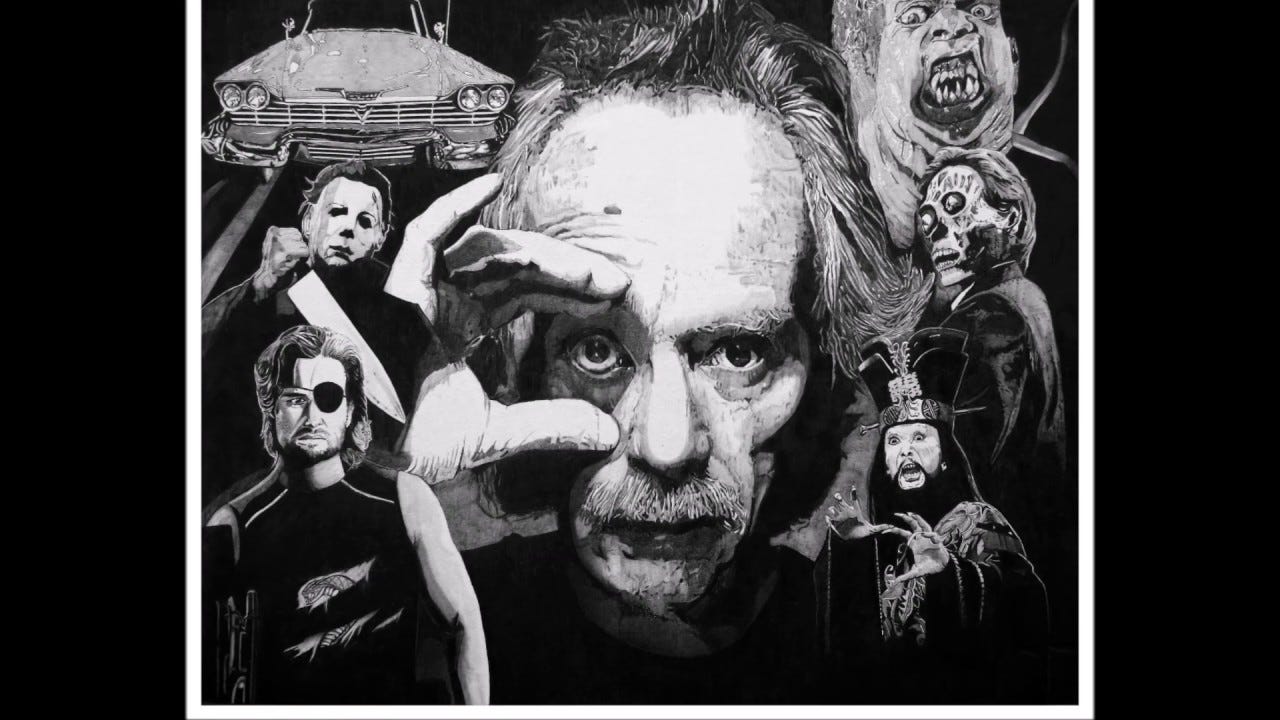

Indeed, the simple act of seriously addressing Carpenter’s career recommends Cumbow’s study to admirers of this underrated popular artist, a man who’s endeared himself to fantasy fans, horror devotees, and science-fiction (SF) aficionados the world over by writing and/or directing such memorable movies as 1978’s slasher-film masterpiece Halloween, 1981’s dystopian prison-break extravaganza Escape from New York, and 1988’s mass-media horror-satire They Live. Indeed, Cumbow’s stimulating analyses of these (and several other) Carpenter films make Order in the Universe a worthy addition to Scarecrow Press’s valuable Filmmakers Series, as well as to any reader’s personal library.

Cumbow frames his smart appraisals of each Carpenter movie within the context of the man’s status as a cinematic auteur primarily concerned with tales of unexpected, ominous, and unknown realms penetrating the confines of quotidian reality. “This is the far deeper, more devastating (and sometimes transfiguring) experience of finding that the order in accord with which one has lived one’s life is not the right one; that some other order altogether controls—and perhaps has always controlled”1 our lives, Cumbow writes in his Introduction, setting the tone—patient, observant, incisive—for his entire book. Through precise considerations of how Carpenter’s plots, characters, themes, and deceptively simple symbolism explore 20th Century America’s restless civic life and spiritual malaise, Cumbow recognizes that Carpenter, still most famous for creating Halloween’s unstoppable psychopath Michael Myers, is a visual artist of the first order.

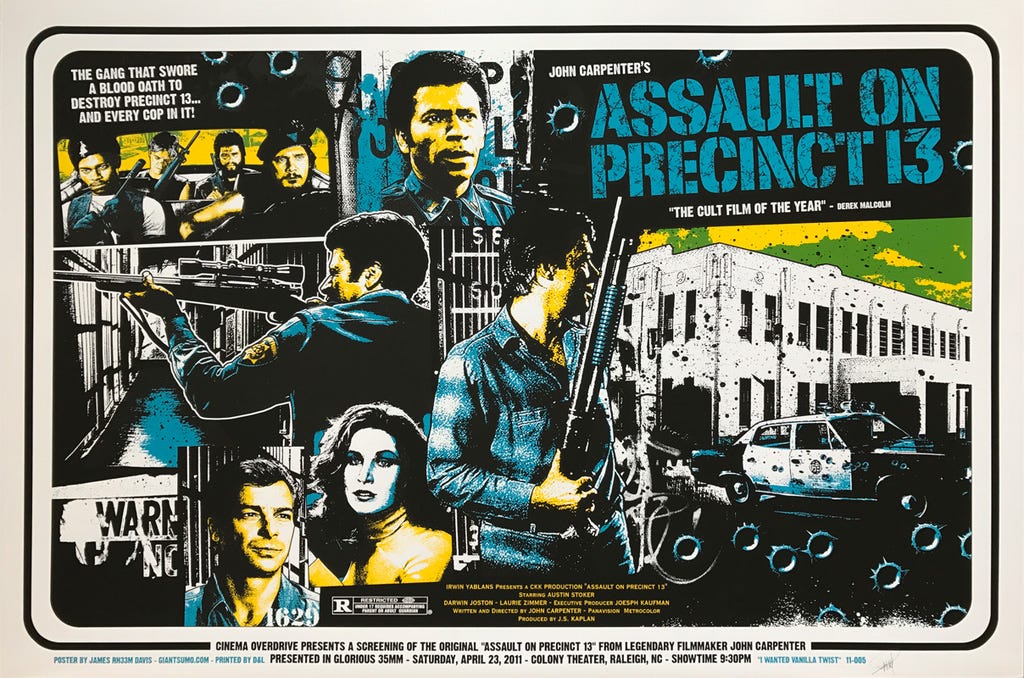

Cumbow’s strengths are nowhere more apparent than in “There Are No Heroes Anymore,” his fourth (and longest) chapter, a superb evaluation of 1976’s Assault on Precinct 13 that exposes this movie as central to Carpenter’s filmic corpus. Combining Carpenter’s respect for Howard Hawks’s artistic renderings of radical individualism with its writer-director’s own mistrust of the progress promised by institutional bodies, both large and small, situates Carpenter squarely in a tradition of postmodern skepticism about collective values. Cumbow’s most significant accomplishment is elucidating how these ideas meld easily, even inevitably, with the fantasy, horror, and SF genres of which Carpenter is a master practitioner. Cumbow’s healthy respect for horror-and-SF filmmaking’s many possibilities is as refreshing as Carpenter’s talent at inflecting stories of good and evil with Hawksian anxieties about collectivism’s utility even as he (Carpenter) demonstrates how the rugged individualism saluted by those rock-ribbed, red-blooded, two-fisted heroes of midcentury American cinema is just as objectionable as allegiance to patriotic groupthink.

Cumbow examines how Carpenter consistently (and skillfully) refuses to endorse simplistic Manichean notions (of good and evil, of law and order, of conformity and chaos) despite returning to the concept of pure evil in film after film (see the marauding street gangs in Assault on Precinct 13, the extraterrestrial shapeshifter that menaces an Antarctic research team in 1982’s The Thing, and the supremely eerie Satanic reverberations of 1987’s Prince of Darkness for three potent examples). Cumbow explains how Carpenter encodes good/evil dualities into his movies’ sly depictions of urban alienation to mold evil characters and malevolent impulses into mythic signifiers that stick in their viewer’s mind long after fading from the screen.

Carpenter’s visions of heaven and hell merging into the white noises and dark spaces of a universe careening out of control reveal evil surreptitiously transforming our everyday world into a place that at first seems unchanged. His movies depict quiet invasions of humdrum existence by malign forces that threaten to dehumanize Carpenter’s viewers no less than his hapless protagonists, thereby renovating how we perceive the world around us. In Carpenter’s films, we must resist evil’s emergence as a presence that exists simultaneously within and beyond our routine and monotonous daily lives even if, by doing so, we risk losing our souls.

2. Smoke & Mirrors

Cumbow, equally adept at highlighting Carpenter’s cinematic reflexivity, demonstrates in convincing detail how several Carpenter movies interrogate the processes of filmmaking, visual storytelling, and screen editing to achieve a metatextual awareness whose sophistication may surprise audiences expecting temporary thrills and harmless diversions, not profound commentaries about the state of our fractious and fallen world. Cumbow’s discussion of Prince of Darkness, one of the best American films of the 1980s, regards this story as, in some measure, a palimpsest of Nigel Kneale’s Quatermass television serials and movies (1953-1979), Don Siegel’s 1956 Cold War fever dream Invasion of the Body Snatchers, Chris Marker’s 1962 photo-montage tour-de-force La Jetée, and Stanley Kubrick’s 2001: A Space Odyssey (1968) and The Shining (1980), to name only a few.

Cumbow’s book, no matter how impressive, stumbles here and there. Order in the Universe’s comprehensive consideration of Carpenter’s films, while a boon that permits Cumbow to trace important themes across the writer-director’s entire career, also pre-empts sustained analyses of some of Carpenter’s best movies. Cumbow, for instance, contends that 1986’s overlooked Big Trouble in Little China, “for all its apparent eclecticism, its spoofery, and its lack of artistic pretension . . . was the purest and most mature Carpenter film to date,”2 an assessment requiring more than the measly four pages Cumbow takes to explain why Big Trouble deserves such high praise (with Kurt Russell’s glorious comic performance as truck-driver extraordinaire Jack Burton, a hilarious 100-minute sendup and takedown of John Wayne’s “the Duke” persona that’s never been equaled, being a good place to start). Such deficiencies aren’t dealbreakers, but they validate the judgment that, if every chapter were as good as Cumbow’s intelligent discussion of Assault on Precinct 13, his book would be an even-more satisfying work of movie criticism.

Order in the Universe, to state the matter succinctly, doesn’t concern itself with deep theoretical ruminations so much as culturally nuanced readings of Carpenter’s filmography. This perhaps-welcome change for audiences wearied by academic jargon shouldn’t worry us too much given Cumbow’s plain-spoken and straight-ahead, yet rigorous prose style. Intellectually provocative and accessibly written, Order in the Universe at long last gives John Carpenter his proper due as an innovative and important filmmaker while accomplishing one of the director’s self-professed goals: “I try,” Carpenter tells Eric Taub in his (Taub’s) 1987 book Gaffers, Grips, and Best Boys, “to do things that I haven’t done before.”3

So, too, does Robert C. Cumbow. By examining Carpenter’s oeuvre with the same intelligence, wit, and enthusiasm that the writer-director infuses into his movies, Cumbow adds a distinctive contribution to our understanding of one of 20th Century America’s great cinematic storytellers. That’s more than enough praise to justify reading Order in the Universe two decades after its inaugural publication, so please, my friends, consult this worthwhile guide to John Carpenter’s films while rewatching, reconsidering, and—best of all—enjoying them all over again.

FILES

NOTES

Robert C. Cumbow, Order in the Universe: The Films of John Carpenter, second edition, Filmmakers Series No. 70, Scarecrow Press, 2000, pg. 2. The emphasis is Cumbow’s.

Ibid., pg. 142.

John Carpenter, quoted in Eric Taub’s Gaffers, Grips, and Best Boys: From Producer/Director to Gaffer and Best Boy, A Behind-the-Scenes Look at Who Does What in the Making of a Motion Picture, St. Martin’s Press, 1987, pg. 69.