Note to The Vestibule’s subscribers: This post re-creates my third and final contribution to the publishing goliath ABC-CLIO’s Enduring Questions Database. Posted on 15 September 2015, I began researching and writing “Reel Nativism” in the final weeks of the remarkably pleasant sabbatical from university teaching that I enjoyed from late-May 2013 to mid-August 2014.

I delivered this piece just before Thanksgiving 2014 to Greenwood Publishing Group editor Nita Lang, who’d taken over the Enduring Questions project from founding editors George Butler and Rebecca Matheson. Yet various internal ABC-CLIO delays—whose origins I no longer recall—made this article’s peer-review-and-revision process more fitful than usual, stretching on longer than I would’ve preferred, but, eventually, this essay saw the light of day (or, at least, the light of online publication).

I do remember Nita asking me to write a fourth Enduring Questions article the same day that SPECTRE, the 23rd James Bond film, premiered (on 6 November 2015), mostly because her email note inviting me to do so was the final message I read before deactivating my smartphone, walking into the movie theatre, and watching Daniel Craig’s fourth outing as 007.

I enjoyed that film much more than some other fans, telling Nita, a fellow Bond enthusiast, in my reply saying “yes” to writing another EQ piece that I thought she’d be pleased with the movie. And she was, telling me that she thought SPECTRE was better than the mixed reviews it received before promising to send a new list of Enduring Questions within a few days.

Then radio silence for weeks, although I was busy enough not to notice this interregnum, only to receive a message from Nita in early 2016 that regime change at ABC-CLIO had elevated a new faction to power. Her incoming bosses promptly shuttered the Enduring Questions Database not because it wasn’t popular with—and not because it wasn’t useful to—their website’s visitors, but because they wanted to create additional databases around more specialized topics. And so, for reasons passing understanding, they concluded that the Enduring Questions project was such a good model that Nita and her EQ team should focus their time and attention upon these ancillary databases rather than keeping the mothership aloft.

And so concluded my participation in the Enduring Questions Database, with a whimper rather than a bang, but that’s simply how it goes in academic publishing, and mainstream publishing too, when newly hired executives disregard the old adage “if it ain’t broke, don’t fix it” in favor of shiny new projects that they hope, pray, and predict will be better, faster, stronger—well, you get the idea.

Yet I’m not complaining too much since I enjoyed writing and revising “Reel Nativism” despite its caustic response to a provocative enduring question, a reply that remains distressingly relevant one decade after its initial publication. The only major updates to this piece that I’ve made, beyond aligning it with The Vestibule’s house style, are the references to Sterlin Harjo’s terrific, three-season television series Reservation Dogs (2021-2023) and to Graham Roland’s excellent, ongoing adaptation of Tony Hillerman’s Joe Leaphorn & Jim Chee novels—titled Dark Winds (2022-Present)—that end Section #2. Otherwise, apart from smoothing the language and syntax of certain passages, this post presents “Reel Nativism” in much the same form that my revised-final draft does.

Like the initial posting of my first EQ article (“Out of the Twilight Zone: American Television Comes of Age”), I haven’t yet located paper or digital copies of “Reel Nativism,” but will continue searching for them and, if they turn up, I’ll post them in the “Files” section below.

Meanwhile, please enjoy reading this essay, which I’ve appreciated revisiting all these years later.

All the best—Jason

Enduring Question

What do depictions of Native Americans in film and television suggest about American culture?

Quick Response

For every promising development, causes for concern and even pessimism exist, so the picture is neither as rosy nor as cheerful as we might hope.

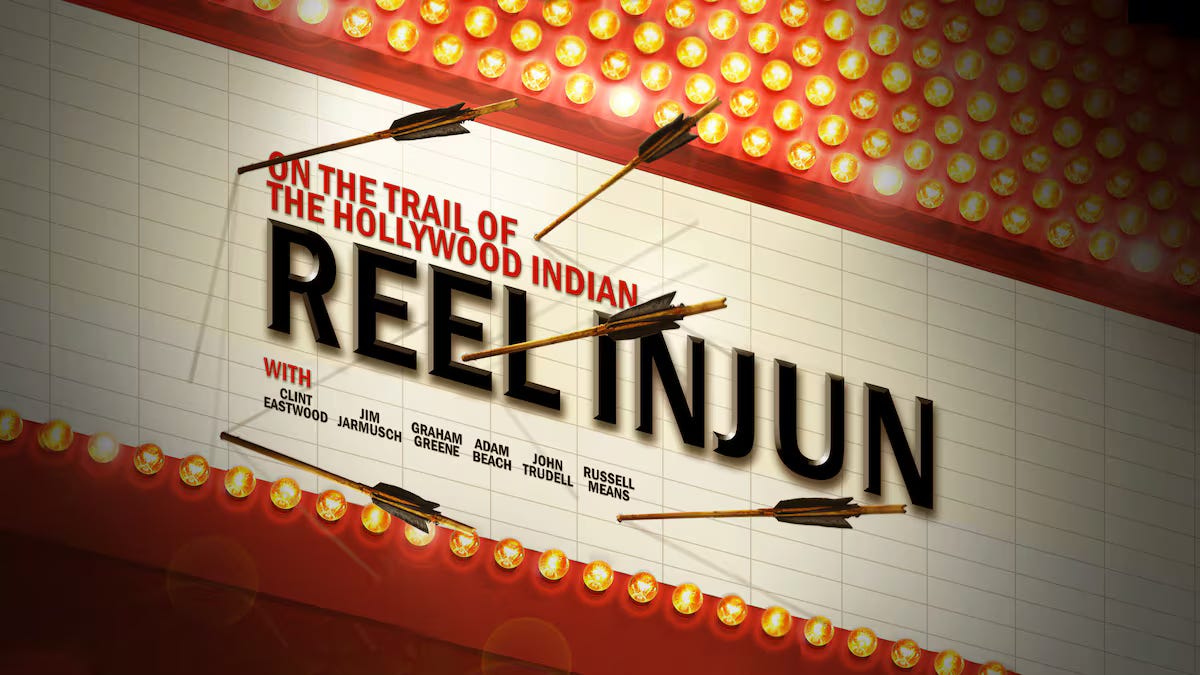

1. Dusk

The fact that comparably few Native Americans take part in writing, directing, and producing American films and television programs allows misrepresentations of Indigenous peoples to proliferate despite the increasingly complex portrayals of such characters seen since the mid-1990s. We can more fully understand this truth by beginning with Neil Diamond: not the lounge singer-cum-Vegas showman extraordinaire, but the Cree-Canadian filmmaker whose 2009 documentary Reel Injun: On the Trail of the Hollywood Indian performs an invaluable service for anyone interested in the question of Native American representation.

Reel Injun, with a song in its heart, reveals how decades of Hollywood filmmaking have so fixed stereotypes about Native Americans in the minds of global audiences that this documentary’s light touch masks its inevitable truth: For most viewers, particularly most American viewers, ideas about nobly savage Native Americans have become so pervasive that they’re now indelible.

This image, Diamond notes, applies to Native viewers as much as anyone else, with his voiceover revealing in Reel Injun’s opening moments, “Growing up on the reservation, the only show in town was Movie Night in the church basement. Raised on cowboys and Indians, we cheered for the cowboys, never realizing we were the Indians.”1 Diamond delivers this line with matter-of-fact aplomb, but its devastating effect makes his film compulsory viewing for every person who’s ever gone to the movies or watched television, meaning, at last count, all of us.

In the same way that Spike Lee’s Bamboozled (2000) makes it impossible for audiences to dismiss the stereotypical representations of Black Americans that one century of Hollywood filmmaking has lodged in our collective consciousness, Diamond’s Reel Injun unveils, persistently and precisely, just how perniciously screen images have damaged America’s cultural understandings of Native peoples.

This last statement is the polite expression of a more troubling truth. American viewers remain so deeply attached to inaccurate and insulting images of Native peoples that we resist works offering more honest portrayals, which discourages Hollywood studios, television networks, and streaming services from hiring Native Americans into prominent positions from which they might demand more realistic screen portrayals of Indigenous characters. Increasing the number of accurate, complex depictions of Native Americans would also, in a salubrious side effect, encourage non-Indigenous filmmakers to eliminate stereotypical portrayals of Native Americans from their productions to redress the long and dismal history of Native representation that Reel Injun so entertainingly documents.

Reel Injun’s great strength is employing affectionate humor with such élan that the viewer can’t help but be swept along by Diamond’s argument, which the documentary baldly announces in its opening textual statement:

In over 4000 films, Hollywood has shaped the image of Native Americans. Classic Westerns like They Died with Their Boots On created stereotypes. Later blockbusters like Little Big Man, One Flew over the Cuckoo’s Nest and Dances with Wolves began to dispel them. Not until a renaissance in Native cinema did films like Once Were Warriors and Smoke Signals portray Native people as human beings.

By interviewing actors (Adam Beach, Graham Greene, and Wes Studi), filmmakers (Clint Eastwood, Chris Eyre, and Zacharias Kunuk), activists (Sacheen Littlefeather, Russell Means, and John Trudell), and film essayists (Angela Aleiss, Melinda Micco, and Jesse Wente) alongside others, Diamond demonstrates how Native American cinematic representations grew in number, complexity, and authenticity during the 20th Century, especially in its final two decades.

The expanding Native film movement of the early 1990s, according to Reel Injun, transformed the longstanding cultural script of malign stereotypes into more authentic Indigenous portrayals, permitting Reel Injun to extol the future of Native moviemaking by praising the Aboriginal film movements growing in prominence across the globe as the 1990s unfolded. Diamond’s film may concern itself with how Hollywood movies depict Native Americans (or, as Diamond himself says, American Indians), but it concludes on a note of undeniable optimism about the future of Native representation in American cinema.

Reel Injun, as an 88-minute documentary, can’t cover everything, but Diamond’s intelligent contributions to discussions about Native people’s onscreen lives outweigh any drawbacks that Reel Injun manifests. The film, however, leaves viewers with the false impression that a new day is just around the corner. Jesse Wente’s and Chris Eyre’s comments about Zacharias Kunuk’s terrific 2001 film Atanarjuat, for instance, are inspiring in their conviction that Native cinema, having emerged from its adolescence, now possesses enough independence to, as Wente says, “tell our stories our way” because “the gaze is ours.”

Diamond’s voiceover claims that Atanarjuat, by so artfully dramatizing the story of an Inuit legend, “has revolutionized Native cinema,” while Eyre refers to Kunuk’s film as both “an inside job” and “the most Indian movie ever made.” These plaudits—along with Wente’s final comment about “the Aboriginal cinematic movement springing up all over the world” and Eyre’s statement that “we’re not asking to be, you know, nobles or righteous or good all the time, we’re asking to be human”—indicate how much promise the work of Native filmmakers holds for global audiences.

Not to be outdone, Robbie Robertson—former lead guitarist and songwriter for The Band (whom Reel Injun identifies as a “Mohawk recording artist”)—exults in this new era of Indigenous filmmaking by saying, “Indians aren’t dead. We’re here, we’re vital. We got something to say, we got something to play.”

2. Night

Robertson’s remarks, accompanied by a score rising to crescendos that pluck the viewer’s heartstrings, suggest that Native cinema has come into its own. Who, then, would imply that this conclusion is anything less than necessary to acknowledging the changes that’ve occurred since the early 20th-Century advent of the Western, the film genre that Reel Injun blames for fostering so many Native stereotypes? Who would hint that the documentary’s final, fifteen-minute paean to Native cinema’s vigor is questionable or problematic?

The answer, perhaps surprisingly, is Neil Diamond, or, at least, Reel Injun: The Movie, the website devoted to his documentary that Diamond oversees. This site’s blog contains excellent short essays that expand upon the documentary’s arguments, themes, and images, especially Jesse Wente’s contribution, titled “Avatar and Twilight: Native Representation on Screen 2.0,” which begins by confessing that Wente’s participation in Reel Injun “was a great reminder of just how far the representation of Native people on screen has come in the century or so of cinema” before noting that “some recent additions to the canon serve as reminders of just how far is left to travel. Watching James Cameron’s Avatar, as well as the last two movies in the ‘Twilight Saga’ brought back some of the emotions I felt when revisiting films from decades past.”2

Wente concedes that Reel Injun’s story of progress is fitful, provisional, and uncertain: “In so many ways, these thoroughly modern blockbusters (modern in both design and intent) rely on many narrative tropes revealed in the Westerns exposed in Reel Injun.”3 Wente can’t ignore the setback that these film franchises represent. Whatever their strengths, “both Twilight and Avatar are deeply rooted colonialist stories that may be inseparable from the dominant culture that crafted them.”4

This final declaration seems incontestable, particularly considering the derisive nicknames for Avatar that, appearing online within hours of the movie’s theatrical release, mocked its neo-colonialist narrative, with A Man Called Blue and Dances with Aliens being especially common. Accounts of Avatar’s regressive Native stereotypes populated film websites for weeks after its December 2009 opening, which occurred six months too late for Neil Diamond to consider in Reel Injun.

This critical backlash decried Avatar’s story of space marine Jake Sully (Sam Worthington) becoming so entranced by the Na’vi people of the lush planetary moon Pandora that, when Jake arrives there in the year 2154, he follows the time-honored tradition of Hollywood films about sensitive White men encountering Indigenous peoples, namely, Jake comes to consider their way of life superior to his own culture’s destructive greed and imperial avarice. Cameron pursues this premise to its logical conclusion, when Jake, thanks to Pandora’s mystical Tree of Souls, transfers his mind into his Na’vi avatar, becoming a ten-foot-tall, blue-skinned member of Pandora’s close-to-the-land, nature-loving people.

Discarding his White body is Jake’s final renunciation of the colonial mindset that powers Avatar’s story of humanity invading Pandora to plunder its resources, necessitating “pacification” of the Indigenous population. Cameron may not have intended to splice Kevin Costner’s Dances with Wolves (1990) with that film’s most obvious cinematic forerunner, Elliot Silverstein’s A Man Called Horse (1970), but Avatar replays the worst clichés of the “going-native Western,” in which White men learn the error of their ways by living amongst a tight-knit band of Native Americans, eventually adapting to their new culture so amenably that they fight invading Federal forces (or enemy tribespeople) on behalf of their newly adopted brothers and sisters.

Such stories, no matter how unreconstructed, retain their narrative power, as Avatar’s record-breaking ticket sales prove. Cameron’s film made more money in less time than any other movie in cinematic history, or, by another measure, more people saw Avatar during its initial theatrical run than all the films by Native American moviemakers during the previous 30 years. This realization—depressingly, sadly, but inevitably—punctures Reel Injun’s cheerful appraisal of Native cinema’s viability as a commercial art form.

We should remain glad, even ecstatic, that Native films continue to be produced, but the hardships their creators endure to secure financing and distribution for their projects must also give us pause. Compared to Avatar’s gigantic financial and cultural influence, even the best-known example of Native American cinema, Chris Eyre’s Smoke Signals (1998)—based upon the fiction of Sherman Alexie, who also wrote the screenplay—is, by comparison, a pinprick.

This realization can’t condemn us to total despair, yet underscores the difficulties facing Indigenous writers, actors, directors, and producers. American mass media remain governed by stories that ignore, elide, or, at best, pay lip service to Native Americans. Even in the 21st Century’s third decade, so few Indigenous people work in positions of creative authority at American film studios, television networks, and streaming services that Avatar’s success is neither a retrenchment from a previous era of expanding opportunity for Native workers nor a reversal of earlier trends, but instead simply continues Hollywood’s extensive history of excluding minority voices from the cultural mainstream (which, in a vicious cycle, Hollywood helps define).

This story is far from new, signifying that the problems Reel Injun diagnoses haven’t abated despite many fine examples of Native cinema, whether Atanarjuat; Smoke Signals; Jonathan Wacks’s Powwow Highway (1989); Sherman Alexie’s The Business of Fancydancing (2002); Michael Linn’s Imprint (2007); or the documentaries that Indigenous filmmakers premiere every year at the American Indian Film Festival, at the First Nations Film and Video Festival, and at the Sundance, Telluride, and Toronto film festivals. The recent uptick in nuanced Native characters appearing in American television dramas—on Saving Grace (2007-2010), Longmire (2012-2017), Banshee (2013-2016), Helix (2014-2015), and The Red Road (2014-2015)—may augur well for future productions, but these series boast neither creators nor showrunners who are Native Americans.

Sterlin Harjo’s beautifully crafted Reservation Dogs (2021-2023) and Graham Roland’s hauntingly realized Dark Winds (2022-Present) are the exceptions that prove this rule. The only two American television series to feature entirely Indigenous writing staffs and, with a few notable divergences, Indigenous casts and production crews, these programs’ existence and quality are nearly miraculous in effect, but the facts that it took so long for these series to reach American television screens and that, as of this writing, they haven’t been repeated provide their own damning commentaries.

3. Dawn?

The Writers (WGA) and Directors (DGA) Guilds of America, for instance, remain controlled by White men, with WGA’s periodic Hollywood Writers Reports (now titled the Hollywood Diversity Reports)—prepared in the 2000s and the 2010s by Darnell M. Hunt, then-director of UCLA’s Ralph J. Bunche Center for African American Studies—showing that Native American writers consistently account for only 0.3 percent of all WGA members and only 0.2 percent of those writers actively working on Hollywood productions. Since all writers must become WGA members to be hired by Hollywood film studios, television networks, and streaming services, these statistics provide accurate snapshots of industry trends.

Hunt’s 2009 report, titled “Rewriting an All-Too-Familiar Story?,” covers the years 2006 and 2007 by breaking down demographic data by racial, ethnic, and gender categories. Native Americans constitute 0.3 percent of all WGA members (21 total members), but only 0.2 percent of writers employed by Hollywood productions during the review period (8 members).5 Native Americans, indeed, ranged from being 0.2 to 0.6 percent of employed WGA writers from 2001 to 2007, normally occupying 0.3 percent of paid positions, while Caucasians ranged from 90.1 to 94.4 percent during the same period.6

These statistics reveal startling truths about minority representation in Hollywood. As Hunt writes in the 2009 report, his previous (2007) report “found that business-as-usual industry practices resulted in virtually no progress for women and minority writers,” causing him to recommend “‘rethinking business as usual’ in the industry,” but with scant progress: “Despite this clarion call, the present report [2009] finds little if any improvement in the employment and earnings of diverse writers in the Hollywood industry.”7 Hunt specifies why: “White males continue to dominate in both the film and television sectors. . . . The minority share of film employment has been frozen at 6 percent since 1999, while the group’s share of television employment actually declined to 9 percent since the last report”8 (released in 2007).

Hunt’s tone remains startlingly measured when confronting repeated evidence of the American entertainment industry’s persistent exclusion of female and minority writers. Yet the figures that Hunt compiles are appalling. His observation in the 2014 Hollywood Writers Report’s executive summary that “as previous reports have concluded, it appears as if minority writers are at best treading water, particularly when we consider that the nation is rapidly becoming more diverse,”9 is, for anyone not dazzled by Hollywood’s self-important glamour, a serious understatement. Both nativism and White domination still rule the day, making the situation for Native writers even bleaker than the position of Black Americans and Latino Americans in the nation’s dream factories.10

Opponents of this pessimistic view may cry that it ignores real progress. Problems persist, they’ll acknowledge, but these issues can only improve as America’s population diversifies. Such negative assessments, Hollywood’s defenders insist, may even prejudice us against sincere White writers who work every day trying to put the best, most inclusive stories on screen.

My considered response to these syrupy claims is: Balderdash. They are cultural clichés—or, more accurately, vomit-inducing bromides—trotted out whenever racial, ethnic, and gender disparities in any aspect of American life come to prominence. Such weak-kneed responses, however, deny the ongoing reality of Hollywood’s dogged—and even fierce—resistance to the principles of equal opportunity, equal representation, and equal consideration.

The fact that so few Native writers, directors, producers, and actors participate in Hollywood’s creative industries has helped drive, by necessity, the Native film movement that Reel Injun applauds. Yet until more Indigenous personnel occupy positions of authority in Hollywood movie studios, television networks, and streaming services, Native cinema will remain outside the mainstream, on the margins, and in the wings. While the small budgets of Indigenous movies often produce films of greater depth than run-of-the-mill Hollywood blockbusters, presenting Native characters in their full humanity won’t become the industry standard until Indigenous creators become what Spike Lee calls “gatekeepers”: People with the power to bankroll and release projects that “tell our stories our way,” to return to Jesse Wente’s evocative formulation. Until that day, which seems long in the future, the depictions of Native characters will perpetuate hackneyed tropes, behaviors, and representations. As Avatar’s success illustrates, such stories earn enormous profits.

American popular culture’s depictions of Native Americans, therefore, tell us that the United States is far from the perfect union to which it aspires. The solution to this problem requires Indigenous filmmakers to enter Hollywood’s boardrooms and corner offices, not the usual hackneyed proposals: 1) Convening committees to study the problem; 2) Holding “national conversations” (whatever they are) about the nativist practices institutionalized in Hollywood’s hiring policies; and 3) Recommending better education about Native American history, cultures, and practices.

Charges of reverse discrimination only obscure Hollywood’s unwillingness to surrender its White-supremacist assumptions unless forced by outside pressure (governmental regulation, legal reform, financial penalties, and boycotts by audiences of all persuasions). The probability of any single remedy occurring, much less all of them, remains so remote that, as good as Reel Injun is, the improvements it heralds remain as distant as the sunset. The Indigenous film movements Jesse Wente describes can’t overcome the financial clout, advertising power, and cultural currency of Hollywood’s industrial machine, meaning that we have miles to go before we can sleep secure in the knowledge that a new era for onscreen portrayals of Native Americans has begun.

This lament is neither a defeat nor a retreat to racial essentialism that allows only Indigenous creators to film stories about Native peoples. Sensitive renderings of Indigenous characters by non-Native directors occasionally appear, with Bruce McDonald’s Dance Me Outside (1994) and Steven Lewis Simpson’s Rez Bomb (2008) being two powerful examples. The failure of Gore Verbinski’s The Lone Ranger (2013) may prevent similar productions from receiving approval in the short term, but the fact that James Cameron intended in 2009 to release three Avatar sequels by 2018 (with only 2022’s second installment, subtitled The Way of Water, so far landing in cineplexes) ensures that regressive portrayals of Native peoples will probably never be far from multiplex screens.

So, all is not lost, but all is far from won. The best guide remains Neil Diamond’s Reel Injun, which faces hard truths about the hurdles that Native Americans encounter when constructing honest onscreen portrayals of themselves. Creative control buttressed by substantial budgets is the coin of the realm in Hollywood, meaning that no one should expect productions written, produced, and directed by Native moviemakers to flood the marketplace anytime soon. We must await the day when Indigenous filmmakers can tell their stories their way without worrying about financing, distribution, and studio interference.

So, yes, the hope persists that such a day will eventually dawn.

Yet it’s a slim hope indeed.

FILES

WORKS CITED

Hunt, Darnell M. “Rewriting an All-Too-Familiar Story?,” 2009 Hollywood Writers Report, Writers Guild of America West, 2009, pg. 43, https://www.wga.org/uploadedFiles/who_we_are/HWR09.pdf.

—. “Turning Missed Opportunities into Realized Ones,” 2014 Hollywood Writers Report Executive Summary, Writers Guild of America West, 2014, pg. 3 and pg. 5, https://www.wga.org/uploadedFiles/who_we_are/hwr14execsum.pdf.

Reel Injun: On the Trail of the Hollywood Indian; directed by Neil Diamond; screenplay by Neil Diamond, Catherine Bainbridge, and Jeremiah Hayes; Rezolution Pictures, Lorber Films, and the National Film Board of Canada; 2009; 88 minutes.

Wente, Jesse. “Avatar and Twilight: Native Representation on Screen 2.0,” Reel Injun Guest Blog, 29 January 2010, http://www.reelinjunthemovie.com/site/blog/guest-blog-jesse-wente/.

FURTHER READING

Aleiss, Angela. Making the White Man’s Indian: Native Americans and Hollywood Movies, Praeger, 2005.

Berkhofer, Robert F. The White Man’s Indian: Images of the American Indian from Columbus to the Present, Vintage Books, 1979.

Griffiths, Alison. “Science and Spectacle: Native American Representation in Early Cinema.” In Dressing in Feathers: The Construction of the Indian in American Popular Culture, edited by S. Elizabeth Bird, Westview Press, 1996, pp. 79-95.

Kilpatrick, Neva Jacquelyn. Celluloid Indians: Native Americans and Film, University of Nebraska Press, 1999.

Marubbio, M. Elise, and Eric L. Buffalohead, editors. Native Americans on Film: Conversations, Teaching, and Theory; University Press of Kentucky; 2013.

Raheha, Michelle H. Reservation Reelism: Redfacing, Visual Sovereignty, and Representations of Native Americans in Film; University of Nebraska Press; 2010.

Singer, Beverly S. Wiping the War Paint Off the Lens: Native American Film and Video, University of Minnesota Press, 2001.

Slotkin, Richard. Gunfighter Nation: The Myth of the Frontier in Twentieth-Century America, University of Oklahoma Press, 1992.

NOTES

Neil Diamond; voiceover narration; Reel Injun: On the Trail of the Hollywood Indian; directed by Neil Diamond; screenplay by Neil Diamond, Catherine Bainbridge, and Jeremiah Hayes; Rezolution Pictures, Lorber Films, and the National Film Board of Canada; 2009; 88 min.

All other quotations from Reel Injun share these credentials.

Jesse Wente, “Avatar and Twilight: Native Representation on Screen 2.0,” Reel Injun Guest Blog, January 29, 2010, http://www.reelinjunthemovie.com/site/blog/guest-blog-jesse-wente/.

Ibid.

Ibid.

Darnell M. Hunt, “Rewriting an All-Too-Familiar Story?,” 2009 Hollywood Writers Report, Writers Guild of America West, 2009, pg. 43, https://www.wga.org/uploadedFiles/who_we_are/HWR09.pdf.

Ibid., pg. 45.

Ibid., pg. 12

Ibid.

Darnell M. Hunt, “Turning Missed Opportunities into Realized Ones,” 2014 Hollywood Writers Report Executive Summary, Writers Guild of America West, 2014, pg. 3 and pg. 5, https://www.wga.org/uploadedFiles/who_we_are/hwr14execsum.pdf.

The Hollywood Diversity Report 2024 Featuring Film—Part 2: Streaming, prepared by UCLA’s Entertainment & Media Research Initiative, shows improvement in women’s and minority representation for films produced by streaming services in the year 2023, stating on Page 2:

Among streaming film leads and streaming total actors, Black, Indigenous, and People of Color (BIPOC) reached or exceeded proportionate representation (45 percent and 48.3 percent, respectively). However, BIPOC remained underrepresented in two key employment positions in 2023:

Less than 2 to 1 among streaming film directors (31 percent)

Less than 2 to 1 among streaming film writers (28 percent)

These mixed results lead the authors to express cautious optimism about future trends, but their Hollywood Diversity Report 2025 Featuring Film—Part 1: Theatrical notes on Page 2 that these trends don’t apply to theatrical releases:

Last year [2024], BIPOC lost ground relative to their White counterparts in all key Hollywood employment arenas examined in the theatrical film sector (i.e., theatrical film leads, directors, writers, and total actors). Consequently, BIPOC remained underrepresented on every major industry employment front in 2024:

Less than 2 to 1 among theatrical film leads (25.2 percent)

Greater than 2 to 1 among theatrical film directors (20.2 percent)

Less than 4 to 1 among theatrical film writers (12.5 percent)

Less than 2 to 1 among total theatrical film actors (32.8 percent)

“One step forward, two steps back” is an epigrammatic way to summarize these results, although Part 2 of this report, which covers streaming films, wasn’t available at the time of writing. This publication may well show progress since the 2024 report’s release, but remaining skeptical about this possibility seems the wisest course for now.